A Twentieth-Century Aboriginal Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: Research Material and Indexes, 1964-1968

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY………………………………………….......page 5 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT……………………………..page 5 ACCESS TO COLLECTION………………………………………….…page 6 COLLECTION OVERVIEW……………………………………………..page 7 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE………………………………...………………page 10 SERIES DESCRIPTION………………………………………………...page 12 Series 1 Research material files Folder 1/1 Abstracts Folder 1/2 Agriculture, c.1963-1964 Folder 1/3 Arts, 1936-1965 Folder 1/4 Attitudes, c.1919-1967 Folder 1/5 Bibliographies, c.1960s MS 5014 C.D. Rowley, Study of Aborigines in Australian Society, Social Science Research Council of Australia: research material and indexes, 1964-1968 Folder 1/6 Case Histories, c.1934-1966 Folder 1/7 Cooperatives, c.1954-1965. Folder 1/8 Councils, 1961-1966 Folder 1/9 Courts, Folio A-U, 1-20, 1907-1966 Folder 1/10-11 Civic Rights, Files 1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/12 Crime, 1964-1967 Folder 1/13 Customs – Native, 1931-1965 Folder 1/14 Demography – Census 1961 – Australia – full-blood Aboriginals Folder 1/15 Demography, 1931-1966 Folder 1/16 Discrimination, 1921-1967 Folder 1/17 Discrimination – Freedom Ride: press cuttings, Feb-Jun 1965 Folder 1/18-19 Economy, Pts.1 & 2, 1934-1967 Folder 1/20-21 Education, Files 1 & 2, 1936-1967 Folder 1/22 Employment, 1924-1967 Folder 1/23 Family, 1965-1966 -

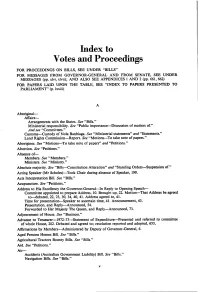

Index to Votes and Proceedings

Index to Votes and Proceedings FOR PROCEEDINGS ON BILLS, SEE UNDER "BILLS" FOR MESSAGES FROM GOVERNOR-GENERAL AND FROM SENATE, SEE UNDER MESSAGES (pp. xlvi, xlvii); AND ALSO SEE APPENDICES 1 AND 2 (pp. 661, 662) FOR PAPERS LAID UPON THE TABLE, SEE "INDEX TO PAPERS PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT" (p. lxxiii) A Aboriginal- Affairs- Arrangements with the States. See "Bills." Ministerial responsibility. See "Public importance-Discussion of matters of." And see "Committees." Customs-Custody of Nola Banbiaga. See "Ministerial statements" and "Statements." Land Rights Commission-Report. See "Motions-To take note of papers." Aborigines. See "Motions-To take note of papers" and "Petitions." Abortion. See "Petitions." Absence of- Members. See "Members." Ministers. See "Ministry." Absolute majority. See "Bills-Constitution Alteration" and "Standing Orders-Suspension of." Acting Speaker (Mr Scholes)-Took Chair during absence of Speaker, 199. Acts Interpretation Bill. See "Bills." Acupuncture. See "Petitions." Address to His Excellency the Governor-General-In Reply to Opening Speech- Committee appointed to prepare Address, 10. Brought up, 22. Motion-That Address be agreed to-debated, 22, 23, 30, 34, 40, 41. Address agreed to, 41. Time for presentation-Speaker to ascertain time, 41. Announcement, 43. Presentation, and Reply-Announced, 54. Forwarded to Her Majesty The Queen, and Reply-Announced, 73. Adjournment of House. See "Business." Advance to Treasurer-1972-73-Statement of Expenditure-Presented and referred to committee of whole House, 282. Debated and agreed to; resolution reported and adopted, 653. Affirmations by Members-Administered by Deputy of Governor-General, 6. Aged Persons Homes Bill. See "Bills." Agricultural Tractors Bounty Bills. See "Bills." Aid. -

Cabinet Records Release from the Director

NORTHERN TERRITORY ARCHIVES SERVICE NEWSLETTER APRIL 2009 N0.34 From the Director Cabinet records Welcome to Records Territory. release In the previous edition I advised that the Northern On the 1st of January 2009, the first Cabinet records Territory Archives Service is no longer responsible created under Northern Territory self-government in for Northern Territory Government recordkeeping. 1978, became open for public access. An amendment to the Information Act was recently The Northern Territory Cabinet consists of introduced in the Legislative Assembly which defines government ministers who meet to make decisions the roles of the Archives Service and the Records on matters such as major policy issues, proposals Service. These are now two separate areas of with significant expenditure or employment Government managing government archives and implications, matters which involve important records respectively. I note that the same archives initiatives or departures from previous arrangements, and research services continue to be provided by the proposals with implications for Australian, state and Northern Territory Archives Service in Darwin and local government relations, legislation, and high level Alice Springs. government appointments. In this issue we bring you the regular update about Cabinet submissions and decisions are an invaluable who is researching what in our search rooms, and record of the decisions of successive Northern updates about some of the unique archives collections Territory administrations, and cover a wide range of that have recently been deposited in our Darwin and issues relating to the social, political and economic Alice Springs repositories. We also provide a glimpse development of the Northern Territory. of some of the promotional activities undertaken by staff across the Territory in the areas of oral history, In 1978, the Northern Territory Cabinet received archives collection, and release of Cabinet records. -

Atomic Thunder: the Maralinga Story

ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume forty-one 2017 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume forty-one 2017 Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Members of the Editorial Board Maria Nugent (Chair), Tikka Wilson (Secretary), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Co-Editor), Liz Conor (Co-Editor), Luise Hercus (Review Editor), Annemarie McLaren (Associate Review Editor), Rani Kerin (Monograph Editor), Brian Egloff, Karen Fox, Sam Furphy, Niel Gunson, Geoff Hunt, Dave Johnston, Shino Konishi, Harold Koch, Ann McGrath, Ewen Maidment, Isabel McBryde, Peter Read, Julia Torpey, Lawrence Bamblett. Editors: Ingereth Macfarlane and Liz Conor; Book Review Editors: Luise Hercus and Annemarie McLaren; Copyeditor: Geoff Hunt. About Aboriginal History Aboriginal History is a refereed journal that presents articles and information in Australian ethnohistory and contact and post-contact history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. -

Collaborative Histories of the Willandra Lakes

LONG HISTORY, DEEP TIME DEEPENING HISTORIES OF PLACE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), Acton, ANU, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. LONG HISTORY, DEEP TIME DEEPENING HISTORIES OF PLACE Edited by Ann McGrath and Mary Anne Jebb Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Long history, deep time : deepening histories of place / edited by Ann McGrath, Mary Anne Jebb. ISBN: 9781925022520 (paperback) 9781925022537 (ebook) Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--History. Australia--History. Other Creators/Contributors: McGrath, Ann, editor. Jebb, Mary Anne, editor. Dewey Number: 994.0049915 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Gerry Mccarthy New World War II Exhibition Open At

Gerry McCarthy MINISTER FOR ARTS & MUSEUMS 15 February 2011 New World War II Exhibition Open at the Northern Territory Library Arts and Museums Minister Gerry McCarthy today invited Territorians to visit a new World War II exhibition currently open to the public at the Northern Territory Library. Mr McCarthy said The Track: 1000 Miles to War focuses on military activities along the Stuart Highway from Alice Springs to Darwin during the Second World War. “This exhibition focuses on the transformation of a rutted dirt stock route to a fully functioning highway supporting crucial military operations during World War II,” Mr McCarthy said. “Through a series of display panels, visitors to this exhibition will learn about a significant history and the enormous benefit the north-south road brought to Territorians and how Alice Springs became the Territory’s main military base following the bombing of Darwin.” This exhibition will be on display at the Library until 20 March 2011 and will then travel the Stuart Highway and be displayed at the Museum of Central Australia in Alice Springs from 15 April to 16 October 2011. Also on display in the Library will be Sam Calder’s flying log book and medals, which are highly treasured by the Library. Calder flew Typhoon planes throughout World War II, completing 120 missions over Europe and receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross. Mr McCarthy also encouraged Territorians to attend a lunchtime talk at the Library this Saturday commemorating the 69 th anniversary of the Bombing of Darwin. “His Honour the Administrator, Mr Tom Pauling AO QC, will host the talk and be joined in conversation by former Administrator, Mr Austin Asche AC QC and at the completion of the talk, Mr Pauling will officially launch the exhibition,” Mr McCarthy said. -

A Centenary of Achievement National Party of Australia 1920-2020

Milestone A Centenary of Achievement National Party of Australia 1920-2020 Paul Davey Milestone: A Centenary of Achievement © Paul Davey 2020 First published 2020 Published by National Party of Australia, John McEwen House, 7 National Circuit, Bar- ton, ACT 2600. Printed by Homestead Press Pty Ltd 3 Paterson Parade, Queanbeyan NSW 2620 ph 02 6299 4500 email <[email protected]> Cover design and layout by Cecile Ferguson <[email protected]> This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the author by email to <[email protected]> or to the National Party of Australia at <[email protected]> Author: Davey, Paul Title: Milestone/A Centenary of Achievement – National Party of Australia 1920-2020 Edition: 1st ed ISBN: 978-0-6486515-1-2 (pbk) Subjects: Australian Country Party 1920-1975 National Country Party of Australia 1975-1982 National Party of Australia 1982- Australia – Politics and government 20th century Australia – Politics and government – 2001- Published with the support of John McEwen House Pty Ltd, Canberra Printed on 100 per cent recycled paper ii Milestone: A Centenary of Achievement “Having put our hands to the wheel, we set the course of our voyage. … We have not entered upon this course without the most grave consideration.” (William McWilliams on the formation of the Australian Country Party, Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates, 10 March 1920, p. 250) “We conceive our role as a dual one of being at all times the specialist party with a sharp fighting edge, the specialists for rural industries and rural communities. -

Civil Aviation Heritage in Australia's Northern Territory

Public History Review Flying Below the Radar: Vol. 28, 2021 Civil Aviation Heritage in Australia’s Northern Territory Fiona Shanahan DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v28i0.7452 The first flight to arrive in the Northern Territory (NT) of Australia is surrounded by debate. Wrigley and Murphy landed in the Territory after flying from Point Cook in Victoria on 8th December 1919. Yet the location of this event remains unclear. Was it Alexandria Station or Avon Downs Station? And why was such an important event not well recorded? Perhaps it was overshadowed by the arrival of the Vickers Vimy and its crew on 10th December 1919 © 2021 by the author(s). This after they successfully completed the world’s first Great Air Race from London to Darwin. is an Open Access article The arrival of these aircraft highlighted their ability to fly long distances, and this must have distributed under the terms impressed many Territorians and hinted at the potential for aviation in the Territory.1 of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license. Citation: Shanahan, F. 2021. Flying Below the Radar: Civil Aviation Heritage in Australia’s Northern Territory. Public History Review, 28, 1–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/phrj. v28i0.7452 ISSN 1833- 4989 | Published by UTS ePRESS | https://epress. -

Special List Index for GRG52/90

Special List GRG52/90 Newspaper cuttings relating to aboriginal matters This series contains seven volumes of newspaper clippings, predominantly from metropolitan and regional South Australian newspapers although some interstate and national newspapers are also included, especially in later years. Articles relate to individuals as well as a wide range of issues affecting Aboriginals including citizenship, achievement, sport, art, culture, education, assimilation, living conditions, pay equality, discrimination, crime, and Aboriginal rights. Language used within articles reflects attitudes of the time. Please note that the newspaper clippings contain names and images of deceased persons which some readers may find distressing. Series date range 1918 to 1970 Index date range 1918 to 1970 Series contents Newspaper cuttings, arranged chronologically Index contents Arranged chronologically Special List | GRG52/90 | 12 April 2021 | Page 1 How to view the records Use the index to locate an article that you are interested in reading. At this stage you may like to check whether a digitised copy of the article is available to view through Trove. Articles post-1954 are unlikely to be found online via Trove. If you would like to view the record(s) in our Research Centre, please visit our Research Centre web page to book an appointment and order the records. You may also request a digital copy (fees may apply) through our Online Enquiry Form. Agency responsible: Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation Access Determination: Open Note: While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of special lists, some errors may have occurred during the transcription and conversion processes. It is best to both search and browse the lists as surnames and first names may also have been recorded in the registers using a range of spellings. -

Ordinary Council Business Paper for April 2020

Ordinary Council Business Paper for April 2020 Monday, 27 April 2020 Civic Centre Mayor Damien Ryan (Chair) ALICE SPRINGS TOWN COUNCIL ORDER OF PROCEEDINGS FOR THE ORDINARY MEETING OF THE THIRTEENTH COUNCIL TO BE HELD ON MONDAY 27th APRIL 2020 AT 6.00PM IN THE CIVIC CENTRE, ALICE SPRINGS 1. OPENING BY MAYOR DAMIEN RYAN 2. PRAYER 3. APOLOGIES 4. WELCOME AND PUBLIC QUESTION TIME 5. DISCLOSURE OF INTEREST 6. MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING 6.1 Minutes of the Ordinary Open Meeting held on 30 March 2020 6.2 Business Arising from the Minutes 7. MAYORAL REPORT 7.1 Mayor’s Report Report No. 83/20 cncl 7.2 Business arising from the Report 8. ORDERS OF THE DAY 8.1 That Elected Members and Officers provide notification of matters to be raised in General Business. 9. DEPUTATIONS Nil 10. PETITIONS Nil Page 2 11. MEMORIALS Nil 12. NOTICE OF MOTIONS 12.1 Cr Matt Paterson – COVID-19 12.2 Cr Eli Melky – COVID-19 12.3 Cr Marli Banks – COVID-19 12.4 Alice Springs Town Council Elected Member COVID-19 Community Support Measures Analysis Report No. 85/20 13. REPORTS OF STANDING COMMITTEES – RECOMMENDATIONS 13.1 Corporate Services Committee 13.2 Community Development Committee 13.3 Technical Services Committee 14. REPORTS OF OFFICERS 14.1 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 14.1.1 CEO Report Report No. 81/20 cncl 14.2 DIRECTOR CORPORATE SERVICES Nil 14.3 DIRECTOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Nil 14.4 DIRECTOR TECHNICAL SERVICES 14.4.1 Sports Facility Advisory Committee nomination Report No. 80/20 cncl 14.4.2 UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Technical Services Development Committee 6 April 2020 15. -

A Critical Sociological Inquiry Into the Aboriginal Art Phenomenon

Hope, Ethics and Disenchantment: a critical sociological inquiry into the Aboriginal art phenomenon by Laura Fisher A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD (Sociology) University of NSW 2012 ii PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Fisher First name: Laura Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD (Sociology) School: Social Sciences and International Studies Faculty: Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences Title: Hope, Ethics and Disenchantment: a critical sociological inquiry into the Aboriginal art phenomenon Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art art has come to occupy a significant space in the Australian cultural landscape. It has also achieved international recognition as one of the most interesting aesthetic movements of recent decades and has become highly valuable within the art market. Yet there is much that remains obscure about Aboriginal art. It seems at once unstoppable and precarious: an effervescent cultural renaissance that is highly vulnerable to malign forces. This thesis brings a critical sociological perspective to bear upon the unruly character of the Aboriginal art phenomenon. It adopts a reflexive and interdisciplinary approach that brings into dialogue scholarship from several fields, including anthropology of art, art history and criticism, post-colonial critique, sociology of art and culture, theories of modernity, theories of cross-cultural brokerage and Australian political history. By taking this approach, the thesis is able to illuminate the intellectual and aesthetic practices, social movements and political events that have been constitutive of Aboriginal art‟s meaning and value from the late 19th Century to the present. -

A Dissident Liberal

A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME PETER BAUME Edited by John Wanna and Marija Taflaga A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Baume, Peter, 1935– author. Title: A dissident liberal : the political writings of Peter Baume / Peter Baume ; edited by Marija Taflaga, John Wanna. ISBN: 9781925022544 (paperback) 9781925022551 (ebook) Subjects: Liberal Party of Australia. Politicians--Australia--Biography. Australia--Politics and government--1972–1975. Australia--Politics and government--1976–1990. Other Creators/Contributors: Taflaga, Marija, editor. Wanna, John, editor. Dewey Number: 324.294 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press CONTENTS Foreword . vii Introduction: A Dissident Liberal—A Principled Political Career . xiii 1 . My Dilemma: From Medicine to the Senate . 1 2 . Autumn 1975 . 17 3 . Moving Towards Crisis: The Bleak Winter of 1975 . 25 4 . Budget 1975 . 37 5 . Prelude to Crisis . 43 6 . The Crisis Deepens: October 1975 . 49 7 . Early November 1975 . 63 8 . Remembrance Day . 71 9 . The Election Campaign . 79 10 . Looking Back at the Dismissal . 91 SPEECHES & OTHER PRESENTATIONS Part 1: Personal Philosophies Liberal Beliefs and Civil Liberties (1986) .