A Working Future for the Seventh State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tocsin | Issue 12, 2021

Contents The Tocsin | Issue 12, 2021 Editorial – Shireen Morris and Nick Dyrenfurth | 3 Deborah O’Neill – The American Warning | 4 Kimberley Kitching – Super Challenges | 7 Kristina Keneally – Words left unspoken | 10 Julia Fox – ‘Gender equality is important but …’ | 12 In case you missed it ... | 14 Clare O’Neil – Digital Dystopia? | 16 Amanda Rishworth – Childcare is the mother and father of future productivity gains | 18 Shireen Morris – Technology, Inequality and Democratic Decline | 20 Robynne Murphy – How women took on a giant and won | 24 Shannon Threlfall-Clarke – Front of mind | 26 The Tocsin, Flagship Publication of the John Curtin Research Centre. Issue 12, 2021. Copyright © 2021 All rights reserved. Editor: Nick Dyrenfurth | [email protected] www.curtinrc.org www.facebook.com/curtinrc/ twitter.com/curtin_rc Editorial Executive Director, Dr Nick Dyrenfurth Committee of Management member, Dr Shireen Morris It was the late, trailblazing former Labor MP and Cabinet Minister, Susan Ryan, who coined the memorable slogan ‘A must be identified and addressed proactively. We need more Woman’s Place is in the Senate’. In 1983, Ryan along with talented female candidates being preselected in winnable seats. Ros Kelly were among just four Labor women in the House of We need more female brains leading in policy development Representatives, together with Joan Child and Elaine Darling. and party reform, beyond the prominent voices on the front As the ABC notes, federal Labor boasts more than double the bench. We need to nurture new female talent, particularly number of women in Parliament and about twice the number women from working-class and migrants backgrounds. -

Votes and Proceedings

1990-91-92 1307 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 107 TUESDAY, 25 FEBRUARY 1992 1 The House met, at 2 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. The Speaker (the Honourable Leo McLeay) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Keating (Prime Minister) informed the House that, on 20 December 1991, His Excellency the Governor-General had appointed him to the office of Prime Minister and had, on 27 December 1991, made a number of changes to other ministerial appointments. The Ministers and the offices they hold are as follows: Representation Ministerial office Minister in other Chamber *Prime Minister The Hon. P. J. Keating, MP Senator Button Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Laurie Brereton, MP Prime Minister *Minister for Health, Housing The Hon. Brian Howe, MP, Senator Tate and Community Services, Deputy Prime Minister Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Social Justice, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Commonwealth- State Relations I Minister for Aged, Family and The Hon. Peter Staples, MP Senator Tate Health Services Minister for Veterans' Affairs The Hon. Ben Humphreys, Senator Tate MP Parliamentary Secretary to the The Hon. Gary Johns, MP Minister for Health, Housing and Community Services *Minister for Industry, Senator the Hon. John Button, Mr Free Technology and Commerce Leader of the Government in the Senate Minister for Science and The Hon. Ross Free, MP Senator Button Technology, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister Minister for Small Business, The Hon. David Beddall, MP Senator Button Construction and Customs *Minister for Foreign Affairs and Senator the Hon. -

A Twentieth-Century Aboriginal Family

Chapter 10 The Northern Territory, 1972 The 1972 Federal election was a time of heightened tension among interest groups in Australia. The Liberal-Country Party coalition had been in power since 1949 and all politically minded people sensed a change. All except those in power. Aboriginal poverty, high infant mortality rates and the question of Land Rights left Aboriginal leaders wondering how they could contribute in the political milieu they were confronted with. Charlie Perkins had been telling me for three or four years that he wanted to ‘get rid of this government’, in particular to show his contempt for the Country Party. Charlie at the time was an Assistant Secretary in the Department of Aboriginal Affairs and in spite of his role as a bureaucrat he was intimately involved in Aboriginal politics. So was I. On many occasions he would express his confidence that change in Aboriginal people’s living conditions were just around the corner while at other times he would be filled with despair. The time frame between accepting the nomination to run for the Northern Territory seat and leaving Sydney was very tight. As a family we had to sell the Summer Hill house to finance getting to, and living in Alice Springs. I had to resign from the Legal Service, make contact with the Australia Party base in Darwin and prepare my thinking for an election campaign. One of the first things I did was to speak to my colleague Len Smith to seek his views about if, and how, I should run my campaign. -

Report X Terminology Xi Acknowledgments Xii

Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee Consideration of Legislation Referred to the Committee Euthanasia Laws Bill 1996 March 1997 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee Consideration of Legislation Referred to the Committee Euthanasia Laws Bill 1996 March 1997 © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISSN 1326-9364 This document was produced from camera-ready copy prepared by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Legislation Committee, and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. Members of the Legislation Committee Members Senator E Abetz, Tasmania, Chair (Chair from 3 March 1997) Senator J McKiernan, Western Australia, Deputy Chair Senator the Hon N Bolkus, South Australia Senator H Coonan, New South Wales (from 26 February 1997: previously a Participating Member) Senator V Bourne, New South Wales (to 3 March 1997) Senator A Murray, Western Australia (from 3 March 1997) Senator W O’Chee, Queensland Participating Members All members of the Opposition: and Senator B Brown, Tasmania Senator M Colston, Queensland Senator the Hon C Ellison, Western Australia (from 26 February 1997: previously the Chair) Senator J Ferris, South Australia Senator B Harradine, Tasmania Senator W Heffernan, New South Wales Senator D Margetts, Western Australia Senator J McGauran, Victoria Senator the Hon N Minchin, South Australia Senator the Hon G Tambling, Northern Territory Senator J Woodley, Queensland Secretariat Mr Neil Bessell (Secretary -

Gove Transition Project

C O N V E N E S P R E S E N T S C O O R D I N A T E S O R G A N I Z E S C O L L A B O R A T E S M E D I A P A R T N E R “First Meeting of the Network of Mining Regions” TRANSITIONING REGIONAL ECONOMIES IN ARNHEM LAND Jim Rogers Regional Executive Director 33,000 풌풎풔 East Arnhem Region Population 16,000 (70% Indigenous) Rio Tinto Bauxite and Alumina Ranger Uranium Mine GEMCO Manganese Nhulunbuy • Township built by Nabalco in late 1960s – early 1970s • Purpose: to support bauxite mining operation and associated refinery • Resident numbers b/n 3000 and 5000 people, nearly all mining related, non-Indigenous and highly transient • The mining titles are linked directly to the township Special Purposes lease – finite • Well serviced regional centre with a capable airport, sea port and other community infrastructure East Arnhem and Gove Peninsula transition A 10-15 Year Plan 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 Ongoing Gove Transition (4years) - Growth and diversification – ~10 years Closure planning and post mining economy – ~10+ years – GOVE TRANSITION: NOVEMBER 2013 “In the end, gas wasn’t enough. It will take 8 months to wind down operations at the refinery. The workforce will reduce from 1450 to 350 people ” Rio Tinto Alcan Transition Director COMMUNITY AND BUSINESS RESPONSE RESPONSE: NT GOVE TRANSITION TEAM On Ground Senior Transition Manager NT Government Dedicated multi-agency project team Working directly with Rio Tinto leadership and Transition Team Darwin Senior Executive Leadership CEs Steering Group Policy and program support -

Funding the Ideological Struggle

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities January 2002 Funding the ideological struggle Damien Cahill The University Of Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Cahill, Damien, "Funding the ideological struggle" (2002). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 1528. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1528 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Funding the ideological struggle Abstract Over the past twenty-five years a radical neo-liberal movement, more commonly known as the 'new right', has launched a sustained assault upon the welfare state, social justice and defenders of these institutions and ideas. In Australia, the organisational backbone of this movement is provided by think tanks such as the Institute of Public Affairs (IPA), the Centre for Independent Studies (CIS), and the Tasman Institute; and forums such as the H.R. Nicholls Society. Central to the movement's efficacy and longevity has been financial support from Australia's corporate sector and industry interest groups. Activists and scholars have produced many articles and books discussing radical neo-liberalism, but the movement has yet to be comprehensively analysed. This article is a contribution towards such a project. What follows is an examination of the relationship between the radical neo·liberal movement and Australia's ruling class; a study of the motivations for corporate funding of neo-liberal think tanks; and an analysis of what impact the movement has had on policy and public opinion. -

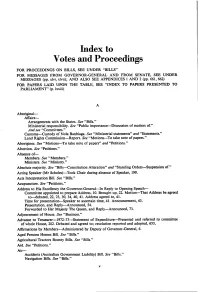

Index to Votes and Proceedings

Index to Votes and Proceedings FOR PROCEEDINGS ON BILLS, SEE UNDER "BILLS" FOR MESSAGES FROM GOVERNOR-GENERAL AND FROM SENATE, SEE UNDER MESSAGES (pp. xlvi, xlvii); AND ALSO SEE APPENDICES 1 AND 2 (pp. 661, 662) FOR PAPERS LAID UPON THE TABLE, SEE "INDEX TO PAPERS PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT" (p. lxxiii) A Aboriginal- Affairs- Arrangements with the States. See "Bills." Ministerial responsibility. See "Public importance-Discussion of matters of." And see "Committees." Customs-Custody of Nola Banbiaga. See "Ministerial statements" and "Statements." Land Rights Commission-Report. See "Motions-To take note of papers." Aborigines. See "Motions-To take note of papers" and "Petitions." Abortion. See "Petitions." Absence of- Members. See "Members." Ministers. See "Ministry." Absolute majority. See "Bills-Constitution Alteration" and "Standing Orders-Suspension of." Acting Speaker (Mr Scholes)-Took Chair during absence of Speaker, 199. Acts Interpretation Bill. See "Bills." Acupuncture. See "Petitions." Address to His Excellency the Governor-General-In Reply to Opening Speech- Committee appointed to prepare Address, 10. Brought up, 22. Motion-That Address be agreed to-debated, 22, 23, 30, 34, 40, 41. Address agreed to, 41. Time for presentation-Speaker to ascertain time, 41. Announcement, 43. Presentation, and Reply-Announced, 54. Forwarded to Her Majesty The Queen, and Reply-Announced, 73. Adjournment of House. See "Business." Advance to Treasurer-1972-73-Statement of Expenditure-Presented and referred to committee of whole House, 282. Debated and agreed to; resolution reported and adopted, 653. Affirmations by Members-Administered by Deputy of Governor-General, 6. Aged Persons Homes Bill. See "Bills." Agricultural Tractors Bounty Bills. See "Bills." Aid. -

Joint Standing Committee

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS, DEFENCE AND TRADE (Foreign Affairs Subcommittee) Reference: Relations with ASEAN DARWIN Wednesday, 13 August 1997 OFFICIAL HANSARD REPORT CANBERRA JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS, DEFENCE AND TRADE (Foreign Affairs Subcommittee) Members: Mr Taylor (Chairman) Mr Barry Jones (Deputy Chairman) Senator Bourne Mr Bob Baldwin Senator Chapman Mr Bevis Senator Ferguson Mr Dondas Senator Harradine Mrs Gallus Senator MacGibbon Mr Georgiou Senator Reynolds Mr Hollis Senator Schacht Mr Lieberman Senator Troeth Mr Leo McLeay Mr Nugent Mr Price Mr Slipper Dr Southcott Matter referred for inquiry into and report on: The development of ASEAN as a regional association in the post Cold War environment and Australia’s relationship with it, including as a dialogue partner, with particular reference to: . social, legal, cultural, sporting, economic, political and security issues; . the implications of ASEAN’s expanded membership; . ASEAN’s input into and attitude towards the development of multilateral regional security arrangements and processes, including the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF); . ASEAN’s attitudes to ARF linkages with, or relationship to, other regional groupings; . economic relations and prospects for further cooperation, including the development of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) and possible linkages with CER; . development cooperation; and . future prospects - in particular the extent to which the decisions and policies of ASEAN affect other international relationships. WITNESSES AWAN, Mr Saqib, Chairman, International Business Council of the Northern Territory Chamber of Commerce and Industry, PO Box 3405, Darwin, Northern Territory 0801 .................................... 330 BEERE, Mr Geoffrey, Technical Consultant, Asia Experience, PO Box 264, Berrimah, Northern Territory 0828 ........................... -

Key Steps to Council Transformation

Regionalisation Strategy ‘BUILDING THE BUSH’ Northern Land Council ‘Building the Bush’ Contents Introduction 3 Shaping our future 6 Who we are 7 What we do 8 Our Land and People 9 Our Structure 12 Our Staff 13 Our Region and Offices 15 Regionalisation Strategy 16 What is Regionalisation? 16 Regionalisation Vision 17 Why Regionalisation? 17 What our Leaders say about Regionalisation 18 Regional Workload Demands 19 How will it happen? 34 What will it look like? 41 What are the benefits? 46 How will we measure? 46 Future Planning? 46 SWOT Analysis 47 Threats/Risks and Mitigation Strategies 48 Annexure A (NLC’s Regional 20 year population projection) 50 Cover photo: NLC staff member Don Winimba Gananbark at Nyinyikay, East Arnhem Land. 2 Northern Land Council ‘Building the Bush’ Introduction The Northern Land Council (NLC) has undertaken significant change over the past five years and is continuing to develop strategic initiatives to ensure that it continues to operate in the most effective, efficient and responsible manner for our constituents in the Top End of the Northern Territory. In recent times there have been a growing number of major resource developments and commercial activities taking place on Aboriginal land. These include: • minerals and energy exploration projects; • infrastructure relating to railway, gas pipeline and army training areas; • national parks; • a significant increase in residential and commercial lot leasing; • enhanced natural resource management; and • pastoral activities. The NLC operating environment is unique, and it is important that the organisation continually adapts to support and foster new and innovative projects and developments that will underpin prosperity in remote Aboriginal communities. -

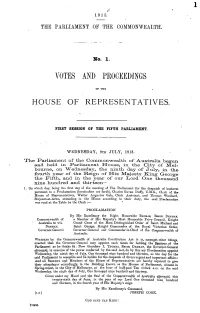

Votes and Proceedings

THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 1. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTH PARLIAMENT. WEDNESDAY, 9TH JULY, 1913. The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, in the City of Mel- Sbourne, on Wednesday, the ninth day of July, in the fourth year of the Reign of His Majesty King George the Fifth, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and thirteen- 1. On which day, being the first day of the meeting of The Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Charles Gavan Duffy, C.M.G., Clerk of the House of Representatives, Walter Augustus Gale, Clerk Assistant, and Thomas Woollard, Serjeaut-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk:- PROCLAMATION By His Excellency the Right Honorable THOMAS, Baron DENMAN, Commonwealth of a Member of His Majesty's Most Honorable Privy Council, Knight Australia to wit. Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and DENMAN, Saint George, Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order, Governor-General. Governor-General and. Commander-in-Chief of the Commonwealth of Australia. WHEREAS by the Commonwealth of Australia Constibution Act it is, amongst other things, enacted that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the s§sions..of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now therefore I, THOMAs, Baron DE:mAN, the Governor-General aforesaid, in exercise of the power conferred by the said Act, do by this my Proclamation appoint Wednesday, the ninth day of July, One thousapd nipe hundred and thirteen, as the day for the said Parliament to assemble and be hplden for the despatch of divers urgent and important affairs: And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly, in the Building known as the Houses of Parliament, situate in Spring-street, in the City of Melbourne, at .the hour of half-past Ten o'clock a.m. -

Thursday 15 August 2019 6910 His Commitment to The

DEBATES AND QUESTIONS – Thursday 15 August 2019 His commitment to the rights of workers not only came through in his legal career but in his passionate support of the Labour movement. He would always attend the annual May Day march and his photographic archives are a treasure trove of history of the Labor Party and the union movement. He continued marching at May Day until he was no longer well enough to do so. The Labor Party owes John a debt. He provided much-needed intellectual and policy grunt over the decades from the 1970s. He also contributed financially to a struggling branch in the dark days of long-term opposition. John's other love was the law. He was a magnificent lawyer. Eloquent, forthright and incredibly smart. Often seen as cantankerous to his opponents, his focus was on obtaining the best outcome for the injured worker or plaintiff. He took cases that no one else would touch and worked to deliver a result no matter what it took. John pursued legal points through to the High Court on a number of occasions. It is not a well-known fact that a Territory man by the name of Roy Wright took on then-PM Malcolm Fraser whom he had seen, on the news, fishing from a billabong illegally. It incensed Mr Wright because he had been fined for fishing from the same billabong. John Waters took up the cudgels on his behalf and the then Prime Minister of Australia had to plead guilty to illegal fishing. His contribution to the jurisprudence of the Territory has been important. -

How Well Did You Listen and Learn for Primary Students?

How well did you listen and learn? A quick recap of your visit to the Parliament of the Northern Territory Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly How many symbols can you remember that are on the Northern Territory’s Coat of Arms? Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly Describe the flag of the Northern Territory? Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly The number of members in the Legislative Assembly is: a. 35 b. 26 c. 25 Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly There are 25 members elected for four years. Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly On what date of the year do we celebrate Self Government? Self Government was granted in 1978 – giving law making power to the Northern Territory Parliament on almost all matters. Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly July 1, 1978 July 1 Swearing in of NT Ministers by Administrator John England on 1 July 1978. Pictured: John England, Paul Everingham, Ian Tuxworth, Marshall Perron, James Robertson, Roger Steele. Northern Territory Library, Northern Territory Government Photographer Collection, PH0093-0188 Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly Who is the Chief Minister of the Northern Territory? Parliamentary Education Services