Centring Anangu Voices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

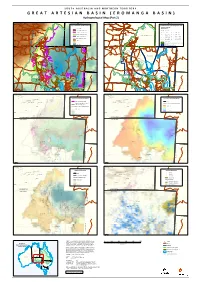

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Community Development

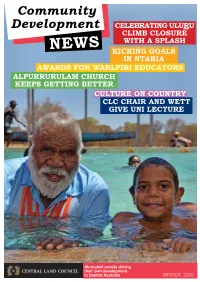

Community Development CELEBRATING ULURU CLIMB CLOSURE WITH A SPLASH NEWS KICKING GOALS IN NTARIA AWARDS FOR WARLPIRI EDUCATORS ALPURRURULAM CHURCH KEEPS GETTING BETTER CULTURE ON COUNTRY CLC CHAIR AND WETT GIVE UNI LECTURE Aboriginal people driving their own development in Central Australia WINTER 2020 ANANGU CELEBRATE ULURU CLIMB 2 CLOSURE AND COMMUNITY PROJECTS Ngoi Ngoi Donald talking Anangu have used the Uluru climb with ABC journalist and closure to show off what they have CLC staff Patrick Hookey. achieved with their share of the national park’s gate money. On the afternoon before the celebration, “THAT MONEY, WE USE IT doubt about the pool’s popularity. traditional owners gave politicians, senior EVERYWHERE FOR GOOD The families visiting Mutitjulu for the climb public servants and selected media a special ONES: SWIMMING POOL, closure celebration and the midday heat tour of Mutitjulu’s pool and surrounding helped boost the number of swimmers. recreation area. BUSH TRIPS, DIALYSIS, LOTS OF GOOD THINGS Elder Reggie Uluru swapped his wheel chair The chief executive of the National Indigenous for a special lift to cool off in the pool with his Australians Agency, Ray Griggs and some of FOR COMMUNITY,” MS grandson Andre. his colleagues, then NT opposition leader Gary DONALD SAID. He was back refreshed as night descended Higgins and journalists from the ABC and the CLC chief executive Joe Martin-Jard and on Talinguru Nyakunytjaku (the sunrise Guardian learned that the project has so far community development manager Ian Sweeney viewing area), beating out the rhythm with invested 14 million dollars in more than 100 talked about the history, governance and future two ceremonial boomerangs as Anangu projects in communities across the region. -

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent Reviewer Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (Cth) 1999 16 April 2020 HEAD OFFICE 27 Stuart Hwy, Alice Springs POST PO Box 3321 Alice Springs NT 0871 1 PHONE (08) 8951 6211 FAX (08) 8953 4343 WEB www.clc.org.au ABN 71979 619 0393 ALPARRA (08) 8956 9955 HARTS RANGE (08) 8956 9555 KALKARINGI (08) 8975 0885 MUTITJULU (08) 5956 2119 PAPUNYA (08) 8956 8658 TENNANT CREEK (08) 8962 2343 YUENDUMU (08) 8956 4118 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 3 2. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... 4 3. OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 5 4. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 5. MODERNISING CONSULTATION AND INPUT ......................................................... 7 5.1. Consultation processes ................................................................................................... 8 5.2. Consultation timing ........................................................................................................ 9 5.3. Permits to take or impact listed threatened species or communities ........................... 10 6. CULTURAL HERITAGE AND SITE PROTECTION .................................................. 11 7. BILATERAL -

The Debilitating Aftermath of 10 Years of NT Intervention

18 Land Rights News • Northern Edition July 2017 • www.nlc.org.au The debilitating aftermath of 10 years of NT Intervention Jon Altman* n the April issue of Land Rights News I This is of special concern to Indigenous I do this because the Intervention was Both communities were established by celebrated the 30th anniversary of the people in the Northern Territory if the heavily promoted as a major project of the Commonwealth in 1959 and 1957 progressive and supportive Blanchard Commonwealth’s constitutional territory improvement and modernisation. Who can respectively and were colloquially referred report Return to Country: the Aboriginal powers remain in place and if, as in 2007, forget Malcolm Brough’s heroic call to to as ‘the Jewel of the Centre’ and ‘the Homelands Movement in Australia. And racial discrimination laws can be suspended ‘Stabilise, Normalise and Exit’ remote NT Jewel of the North’: these were to be the I wondered what celebration or reproach at the whim of the government of the day. communities, the delivery of what can be two demonstration communities where the the 10th anniversary of the Northern thought of as a domestic ‘Marshall Plan’ to Welfare Branch was going to show to all Third are the views expressed by Territory National Emergency Response, demonstrate the developmental powers of how modernisation and development could Indigenous community leaders who are the Intervention that was militaristically the Australian government in a jurisdiction and should be delivered. also subjects of the Intervention, several launched with extraordinary media fanfare where owing to a quirk of the Australian whom I heard present views in two events In 1972 when policy shifted to self- on 21 June 2007 might elicit. -

Submission to the Northern Territory Suicide Prevention Strategic Review

Central Australian Aboriginal Congress 30 July 2017 Central Australian Aboriginal Congress Submission to the Northern Territory Suicide Prevention Strategic Review 30 July 2017 Submitted by: Donna Ah Chee Chief Executive Officer Central Australian Aboriginal Congress Aboriginal Corporation PO Box 1604, Alice Springs NT 0871 T: 08 89514401 E: [email protected] 1 Central Australian Aboriginal Congress 30 July 2017 Executive summary The Central Australian Aboriginal Congress (Congress) is the largest Aboriginal community-controlled health service (ACCHS) in the Northern Territory, providing a comprehensive, holistic and culturally- appropriate primary health care service to more than 14 000 Aboriginal people living in and nearby Alice Springs each year as well as the remote communities of Ltyentye Apurte (Santa Teresa), Ntaria (Hermannsburg) and Wallace Rockhole, Utju (Areyonga), Mutitjulu and Amoonguna. The suicide rate for Aboriginal Australians is almost twice the rate for non-Aboriginal Australians (AIHW, 2016). This submission to the Northern Territory Government’s development of a Suicide Prevention Strategic Plan addresses suicide prevention from a social determinants, population health and primary prevention perspective, as well as from a mental health service delivery perspective. Particular attention is given to young Aboriginal people who have highest national rates of suicide, which can be largely attributed to unhealthy early childhood development, linked to disadvantage. Key issues raised in this submission are: . That suicide in Aboriginal communities is fundamentally linked to disempowerment, disadvantage and the social determinants of health. Unhealthy brain development, self-regulation and coping skills in early childhood are linked to suicide. This is a key issue for young Aboriginal people who are falling well behind in the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) by age 5. -

Chapter 9: Northern Territory Intervention and Indigenous Land

Chapter 9 187 Northern Territory intervention and Indigenous land The federal government on 21 June 2007 announced measures to tackle sexual abuse against Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory. The legislation it passed to implement the measures has significant implications for Aboriginal owned and controlled land. This chapter sets out the main provisions in that legislation that affect land. Concerns are identified. A more comprehensive analysis of the intervention in the Northern Territory and human rights is set out in my Social Justice Report 2007. In that report I provide an overview of the main human rights standards and legal obligations relevant to the government’s intervention. In this Native Title Report 2007 I focus on native title and land issues. The areas addressed are: n compulsory five-year leases; n town camps; n effects of other laws; and n rights in construction areas and infrastructure. Overview Legislation giving effect to the Australian Government’s intervention into Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory received Royal Assent1 on 17 August 2007. The main provisions dealing with the federal government’s acquisition of rights, titles and interests in land are contained in Part 4 of the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act 2007 (Cth) (NTNER Act). There are also provisions dealing with infrastructure in Schedule 3 (Infrastructure) of the Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and Other Legislation Amendment (Northern Territory National Emergency Response and Other Measures) Act 2007 (Cth) (FCSIA(NTNER) Act). That Act amends the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) (ALRA) inserting Part IIB (Statutory rights over buildings or infrastructure). -

Submission To

Central Australian Aboriginal Congress submission to: the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into the Social and Economic Benefits of Improving Mental Health About Congress Central Australian Aboriginal Congress (Congress) is the largest Aboriginal community-controlled health service (ACCHS) in the Northern Territory, providing a comprehensive, holistic and culturally-appropriate primary health care service to more than 14 000 Aboriginal people living in Alice Springs each year as well as the remote communities of Ltyentye Apurte (Santa Teresa), Ntaria (Hermannsburg) and Wallace Rockhole, Utju (Areyonga), Mutitjulu and Amoonguna. Congress operates within a comprehensive primary health care (CPHC) framework, providing a range of services in remote areas of Central Australia. Alongside general practice, services and programs on issues such as alcohol, tobacco and other drugs; early childhood development and family support; and mental health and social and emotional well-being are also provided. We also advocate for those social determinants of health (both physical and mental) including education, housing and justice. About this submission Congress has written a number of submissions relevant to the terms of reference of the inquiry. They include addressing the factors that are fundamental to good health and economic and social participation, as well as mental health services. The main arguments and recommendations are outlined below, along with links to the related submissions which are clearly referenced with research evidence and data to support our reasoning. To view the full suite of our submissions, please see https://www.caac.org.au/aboriginal-health/policy-submissions-publications. Determinants of good mental health and participation Poor mental health is heavily associated with social inequality and disempowerment, which includes the specific historical and contemporary issues experienced by Aboriginal peoples. -

Outback Australia - the Colour of Red

Outback Australia - The Colour of Red Your itinerary Start Location Visited Location Plane End Location Cruise Train Over night Ferry Day 1 healing. The flickering glow of this evening's fire, dancing under the canopy of a Arrive Ayers Rock (2 Nights) starry Southern Hemisphere sky, is the perfect accompaniment to your Regional 'Under a Desert Moon' Meal. This degustation menu with matching wines is the Feel the stirring of something bigger than you as you arrive in Ayers Rock Resort perfect end to the day. Sit back and listen to the sounds of the outback come alive (flights to arrive prior to 2pm), only 20 km from magical, mystical Uluru and the at night in the company of new friends. launchpad to Australia's spiritual heart in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. This afternoon, you'll travel to Uluru as the day fades away, the outback sun bidding a Hotel - Kings Canyon Resort, Deluxe Spa Rooms fiery farewell. Uluru towers over the Northern Territory's remote landscape, the perfect backdrop for this evening's Welcome Reception. Included Meals - Breakfast, Lunch, Regional Dinner Day 4 Hotel - Sails in the Desert, Ayers Rock Resort Kings Canyon - Alice Springs Included Meals - Welcome Reception Gaze across the deep chasm at the edge of Kings Canyon as you embark on the Day 2 spellbinding 6 km sunrise Rim Walk, past the sandstone domes of the 'Lost City' Uluru Sightseeing and down the stairs to the lush 'Garden of Eden'. Or you can opt for a gentler stroll along the canyon creek bed, treading in the footsteps of the Luritja people Wake early, taking time to pause and contemplate the mesmerising sunrise over who once found sanctuary amidst the Itara trees at the base of the canyon. -

Exhibit 4.204.14

ANZ.800.772.0092 Identified ATMs Location No. Site Name Community Locality State 1. Aherrenge Community Store Aherrenge via Alice Springs NT 2. Ali Curung Store Ali Curung NT 3. Mount Liebig Store Mount Liebig NT 4. Aputula Store Aputula via Alice Springs NT 5. Areyonga Supermarket Areyonga NT 6. Arlparra Community Store Utopia NT Atitjere Homelands Store Aboriginal 7. Atitjere NT Corporation 8. Barunga Store Barunga via Katherine NT 9. Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation #1 Maningrida NT 10. Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation #2 Maningrida NT 11. Belyuen Store Cox Peninsula NT 12. Canteen Creek Store Davenport NT 13. Croker Island Store Minjilang (Crocker Island) NT - - 14. Docker River Store Kaltukatjara (Docker River) NT 15. Engawala Store Engawala NT 16. Finke River Mission Store Hermannsburg via Alice Springs NT 17. Gulin Gulin Store Bulman via Katherine NT 18. lmanpa General Store lmanpa WA via Alice Springs NT NT 19. lninti Store Mutitjulu via Yulara NT 20. Jilkminggan Store Mataranka NT 21. MacDonnel Shire Titjikala Store Titjikala via Alice Springs NT 22. Maningrida Progress Association Maningrida NT 23. Milikapiti Store #1 Milikapiti, Melville Island NT 24. Milikapiti Store #2 Milikapiti, Melville Island NT 25. Nauiyu Store Daly River NT 26. Nguiu Ullintjinni Ass #1 Bathurst Island NT 27. Nguiu Ullintjinni Ass #2 Bathurst Island NT 28. Nguiu Ullintjinni Ass #3 Bathurst Island NT 29. Nguru Walalja Yuendumu NT 30. Nyirripi Community Store Nyirripi NT 31. Papunya Store Papunya via Alice Springs NT 32. Pirlangimpi Store Melville Island NT 33. Pulikutjarra Aboriginal Corporation Pulikutjarra NT 34. Santa Teresa Community Store Santa Teresa NT ANZ.800.772.0093 Location No. -

51 51 51 in Dealing with These Matters, The

In dealing with these matters, the department The cameras will be a safety tool for officers considers all the circumstances, including the to reduce incidents of complaints and assaults psychological and social needs of the tenancy, and to gather evidence and record antisocial and attempts to engage with tenants to develop behaviour, damage and other issues with public strategies to help them sustain their tenancy. housing premises. This includes referring tenants to tenancy support programs delivered by non-government Central Australia Renal organisations that are funded by the department. Accommodation project The Visitor Management Policy helps the On 22 June 2015, the Australian and Northern department manage public housing visitors. Territory governments struck a $10 million It supports tenants to maintain positive agreement for the delivery of family-centric neighbourhood community relationships, renal accommodation in Alice Springs and manage their private space and protect the Tennant Creek and dialysis infrastructure and quiet environment of their properties and the staff accommodation in Kaltukatjara, Papunya neighbourhood. and Mount Liebig. The renal infrastructure and accommodation will allow better access to renal Terminations and possessions care and accommodation for remote Central of public housing Australian renal patients and their families. Public housing properties are managed in Following a public competitive process, the Central accordance with the Housing Act and the Residential Australian Affordable Housing Company (CAAHC) Tenancies Act. When a tenant breaches their was selected to refurbish and manage 10 homes legal obligations, the department may initiate - eight in Alice Springs and two in Tennant Creek. compliance action, including terminating a tenancy In August 2016, CAAHC started upgrading the THE DEPARTMENT and taking possession of a premises. -

Wallace Rockhole Is Open for Business…

MacDonnell Regional Council Staff Newsletter SEPTEMBER 2015 volume 7 issue 3 Developing supportive communities communitiesLiveable communitiesEngaged A organisation COUNCIL GOAL COUNCIL GOAL COUNCIL GOAL COUNCIL GOAL #1 #2 #3 #4 Despite being a small community Wallace Rockhole has always shown great initiative to get things done Wallace Rockhole is open for business… Following the completion of MacDonnell Regional Council’s upgrade of the access road linking Wallace Rockhole to Larapinta Drive, tourists can now drive regular cars to experience the rock art and dot painting tours the community offers. Along with the road upgrade, a recent announcement by the Federal Government to install a mobile phone tower at this and three other communities, in the coming years will add to their accessibility. All this follows Wallace Rockhole being named the first ever community to be awarded a Tidy Town 4 Gold Star Tourism Award, after many years of community support for its cultural tourism infrastructure and services… Find out the latest instalments at Wallace Rockhole and other communities of the MacDonnell Regional Council inside MacDonnell Regional Council Staff Newsletter SEPTEMBER 2015 volume 7 issue 3 page 2 Welcome to MacDonnell Regional Council, CEO UPDATE We have all been very busy since the last MacNews finalising Our Regional Plan, meeting our Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and finishing off another financial year full of improvements to the lives of our residents. At our most recent Council meeting, the KPI Report for the past financial year was presented, showing an outstanding effort across all areas of the MacDonnell Regional Council through some very impressive results.