She Went in Haste to the Mountain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assumption Parking Lot Rosary.Pub

Thank you for joining in this celebration Please of the Blessed Mother and our Catholic park in a faith. Please observe these guidelines: designated Social distancing rules are in effect. Please maintain 6 feet distance from everyone not riding parking with you in your vehicle. You are welcome to stay in your car or to stand/ sit outside your car to pray with us. space. Anyone wishing to place their own flowers before the statue of the Blessed Mother and Christ Child may do so aer the prayers have concluded, but social distancing must be observed at all mes. Please present your flowers, make a short prayer, and then return to your car so that the next person may do so, and so on. If you wish to speak with others, please remember to wear a mask and to observe 6 foot social distancing guidelines. Opening Hymn—Hail, Holy Queen Hail, holy Queen enthroned above; O Maria! Hail mother of mercy and of love, O Maria! Triumph, all ye cherubim, Sing with us, ye seraphim! Heav’n and earth resound the hymn: Salve, salve, salve, Regina! Our life, our sweetness here below, O Maria! Our hope in sorrow and in woe, O Maria! Sign of the Cross The Apostles' Creed I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Ponus Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. -

Catholic Life – March 2019

CA HO IC V IFE LDiocese of Lismore Tweed Coast to Camden Haven www.lismorediocese.org March 2019 Vol.17 No.1 Panama Hosts World Youth Day 2019 NO FEES Looking for Work? Looking for Workers? Find us at THE BISHOP Writes What are you doing for Lent? hat’s the question Catholics often ask each other in the 40 days Tleading up to Easter. I would like to ask a different question – “Why do something for Lent?” So often from Ash Wednesday until Easter, we take on a regime of self- denial or active charity, but why? We are about to celebrate the most important event in world history; the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. What made his death so important was the freedom with which he went to this death. It was not forced on him, he chose it. This freedom made his death a paramount act of Love. Without selfishness and in total dedication to his father and to those around him, he gave up his life. He had a radical freedom to die. His resurrection comes in the wake of this freedom. is slavery to desires and is the epitome denial is not sufficient. We cannot We don’t have this kind of freedom, of selfishness. We don’t choose, instead achieve freedom by ourselves. An we are not able to love as Jesus loved. others tell us what we want and we acute experience of our own weakness Yet love is what defines and gives follow them. and impossibility leaves us with two meaning to life. -

St. Boniface Parish 1860-2005

St. Boniface Parish 1860-2005 Saint Boniface Parish A Pictorial Record of The Faith and History of a People by Patricia Richardson Published on the occasion of the Suppression of the Parish of St. Boniface July 1, 2005 By order of the Archdiocese of St. Louis, Missouri Table of Contents Page No. Pastor, Reverend James C. Gray 4 Dedication 5 St. Boniface Staff 6 Choir Director 7 Former Pastors 8 Former Assistant Pastors 9 St. Boniface History 10 St. Boniface photos 11 Historical Plaque 12 St. Boniface Time Line 13-15 Saint Boniface 16 Rectory and Grotto 17 School and Convent 18 History of the Bells 19 The Tower Clock 20 St. Columbkille 21 Covadonga – The Spanish Mission 22 St. Boniface Church Interior 23 Introduction to Stain Glass Windows 24 Stain Glass Windows 25-30 Credits 31 Reverend James C. Gray Pastor, January 15, 2001 to July 1, 2005 Dear Parishioners and Friends of St Boniface: Peace How does one sum up 145 years of accomplishment, dedication and service to God and the Church? From Fr. Gamber to myself, from the original German core to the admixture of Irish, Italians, Spanish and others, ours has been a story of families and their belonging to this greater family of St. Boniface. In such a short space as this, the task is impossible. So I will speak here not of the history or the story of this faith filled and faithful community, but of its tradition. From the beginning, St. Boniface Parish was and has remained a symbol of its people and priests; a symbol of the values and aspirations of the courageous Germans who came to this wilderness from the civilized climes of their homeland to create a better life for themselves and their posterity in this land of opportunity and freedom. -

Blasphemous Titles of Rome’S Mary Goddess

Blasphemous Titles Of Rome’s Imaginary Mary Goddess The following list of aggrandizing titles bestowed upon the Catholic Mary confirms just how far the Church of Rome has gone to elevate their false version of Mary to goddess status. It appears as if they have exceeded the idolatry of ALL pagan goddess worshippers combined. As you can see from the list below, Rome has borrowed attributes from many pagan goddesses in the titles “Our Lady Of”, “Mother Of” and “Virgin Of”. The Catholic Church has also searched the Bible far and wide in order to misapply attributes to Mary that she never had or that belonged to some other biblical person, in an effort to create their deified version of Mary. The true biblical Mary who gave birth to the Lord Jesus Christ – and who did not remain a virgin – would be shocked and revolted by the glorification of herself by Catholics, that so far overshadows the attention and glory given by Catholics to Jesus Christ, the Savior of the world. Massive List Of Titles Of The Catholic Virgin Mary Adam’s Deliverance Advocate of Eve Advocate of Sinners All Chaste All Fair and Immaculate All Good Annunciation by Saint Gabriel Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Aqueduct of Grace Archetype fo Purity and Innocence Ark Gilded by the Holy Spirit Ark of the Covenant Assumption into Heaven Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Basillica of Saint Mary Major Blessed Among Women Blessed Virgin Mary Bridal Chamber of the Lord Bride of Christ Bride of Heaven Bride of the Canticle Bride of the Father Bride Unbrided Cause of Our Joy Chosen -

Titles of Mary

Titles of Mary Mary is known by many different titles (Blessed Mother, tion in the Americas and parts of Asia and Africa, e.g. Madonna, Our Lady), epithets (Star of the Sea, Queen via the apparitions at Our Lady of Guadalupe which re- of Heaven, Cause of Our Joy), invocations (Theotokos, sulted in a large number of conversions to Christianity in Panagia, Mother of Mercy) and other names (Our Lady Mexico. of Loreto, Our Lady of Guadalupe). Following the Reformation, as of the 17th century, All of these titles refer to the same individual named the baroque literature on Mary experienced unforeseen Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ (in the New Testament) growth with over 500 pages of Mariological writings and are used variably by Roman Catholics, Eastern Or- during the 17th century alone.[4] During the Age of thodox, Oriental Orthodox, and some Anglicans. (Note: Enlightenment, the emphasis on scientific progress and Mary Magdalene, Mary of Clopas, and Mary Salome are rationalism put Catholic theology and Mariology often different individuals from Mary, mother of Jesus.) on the defensive in the later parts of the 18th century, Many of the titles given to Mary are dogmatic in nature. to the extent that books such as The Glories of Mary (by Other titles are poetic or allegorical and have lesser or no Alphonsus Liguori) were written in defense of Mariology. canonical status, but which form part of popular piety, with varying degrees of acceptance by the clergy. Yet more titles refer to depictions of Mary in the history of 2 Dogmatic titles art. -

01-88-Contents FINAL-V5.Qxd

July/AugustJuly August 2007 Magazine Tradition Family and Property® A Thirty-Inch Statue of Our Lady of Fatima Only $400! Don’t miss this superb opportunity! Make a great decision and enthrone in your home this beautiful 30-inch statue of Our Blessed Mother as she appeared in Fatima. Hand painted and complete with Rosary, the statue also comes with a detailed gold crown filled with maroon velvet. The globe symbolizes Our Lady, Queen of the world, and the star symbolizes the Morning Star! Limited supply! With your purchase, Look into her eyes! Exquisite receive a FREE copy of Jacinta’s Story, a sixty- hand-painted detail gives her page hardbound children’s book written and the look of the beautifully illustrated by Andrea F. Phillips. mother she is. Your children will become rapt little angels as they listen to the Fatima story as retold imaginatively by Blessed Jacinta. FREE With order of statue BOOK Jacinta’s Story The story of Fatima through the eyes of Blessed Jacinta FREE! Sixty-page hardbound book for your children with purchase of a statue of Our Blessed Mother. Call: 1-888-317-5571 Contents July/August 2007 Cover: Our Lady of Covadonga and the Cave from where Don Pelayo launched the eight-hundred-year fight to reclaim Spain for Christendom. COMMENTARY Fatima: An Appeal to Beauty, Purity and Reparation 4 IN MEMORIAM Eugenia Garcia Guzmán 7 COVER STORY Don Pelayo and the Reconquista of Spain 8 Page 13 ANF PROGRESS REPORT Nationwide Public ! Spreading Public Square Rosaries 13 Square Rosaries— ! Pro-Homosexual Conference at DePaul Heeding Our Lady’s University Tramples Catholic Identity 14 request for prayer ! Another Seven Regional Conferences 14 and penance. -

Appearances of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Appearances of the Blessed Virgin Mary The Roman Catholic Church has approved the following 15 apparitions of the Blessed Virgin Mary, who as our Spiritual Mother, comes to urgently remind us how to reach heaven through the graces bestowed upon us by her son, our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. Our Lady of Betania in Venezuela, 1976-1990 Our Lady of Kibeho, Rwanda, 1981-1989 Our Lady of Akita, Japan, 1973 Our Lady of Zeitoun, Egypt, 1968 Our Lady of Amsterdam, Holland, 1945-1959 Our Lady of Banneux, Belgium, 1933 Our Lady of Beauraing, Belgium, 1932-1933 Our Lady of Fatima, Portugal, 1917 Our Lady of Pontmain, France, 1871 Our Lady of Good Help, Champion, Wisconsin, USA 1859 Our Lady of Lourdes, France, 1858 Our Lady of La Salette, France, 1846 Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal, Paris, 1830 Our Lady of Laus, France, 1664-1718 Our Lady of Guadalupe, Mexico, 1531 Amazingly, there have been hundreds of other apparitions..... and we will visit some of those as well— especially to Emma de Guzman. Mother of Divine Grace Kingston, Ontario, Canada 1991-2014 Soledad Gaviola Emma de Guzman Dec. 21, 1946 – March 4, 2002 LaPieta Visionary, Mystic Kingston Prayer Group Seer INTRODUCTION In 1994 Jack Manion invited me, Doug Norkum, to go with him to a meeting of the LaPieta Prayer Group here in Kingston at 934 Kilarney Crescent. The wonderful ensuing spiritual experiences inspired me in those early days to immerse myself once again in my Roman Catholic faith. However, the following testimony is about a very humble servant of God named Emma de Guzman, who, through the presence and grace bestowed by the Blessed Virgin Mary, has had many miracles emanate in her presence. -

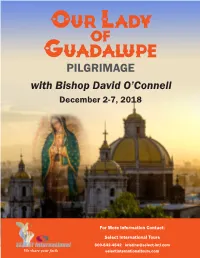

PILGRIMAGE with Bishop David O’Connell December 2-7, 2018

Our Lady of Guadalupe PILGRIMAGE with Bishop David O’Connell December 2-7, 2018 For More Information Contact: Select International Tours 800-842-4842 [email protected] We share your faith selectinternationaltours.com WHAT’S THE ITINERARY December 2, DAY 1, Sunday: DEPART U.S.A COST? Depart for Mexico City. Upon arrival you are greeted by our tour escort and transferred Land and Air to the hotel. Dinner at the hotel, in the historical area of the city, an active area filled with shops, markets and restaurants. Welcome Mass at Our Lady of Good Remedies where we also see the giant statue of St. Michael the Archangel. In the evening we $1899.00 see the Mariachi bands playing in Garibaldi Square. Overnight Mexico City. (Dinner Land Only at a local restaurant) Dec. 3, DAY 2, Monday: MEXICO CITY – OUR LADY OF $1399.00 GUADALUPE – PYRAMIDS OF THE SUN AND THE MOON Morning buffet breakfast. After breakfast, transfer to the Shrine of Our Lady of Gua- Single Supplement dalupe (Patroness of the Americas), by way of the Plaza of the Three Cultures. We will visit the Church of Santiago Tlatelolco where St. Juan Diego was baptized. This plaza $399.00 is important as it symbolizes the unique blend of pre-Hispanic, and Hispanic cultures Deposit due August 20, 2018 that make up Mexico. Continue to the Shrine of Guadalupe built in response to Our Final payment due October 1, 2018 Lady’s request to the visionary, St. Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin. Upon arrival at the Shrine, we will celebrate Mass as we marvel at the brilliantly colored Basilica. -

Shrines of Mexico

Nativity Terms and Conditions Pilgrimage 9-Day Pilgrimage to the Shrines of Mexico Led by Fr. Juan Carlos López and Deacon Guadalupe Rodríguez September 12 – 20, 2021 Cost Round-Trip Air from $2,649 per person Austin, TX For more information, please contact Deacon Guadalupe Rodríguez (512) 364-2795 | [email protected] or visit: https://nativitypilgrimage.com/frjuan-dcnguadalupe Follow Us on Social Media! nativitypilgrim nativitypilgrimage @nativitypilgrimage Daily Itinerary Inclusions • Round-trip airfare • Land transportation as per itinerary • Hotel accommodations • Breakfast and dinner • Airport taxes, fuel surcharges, and fees • Daily Mass • Protection Plan (medical insurance) Non-Inclusions • Tips for your guide and drivers • Lunch • Optional Deluxe Protection Plan (trip cancellation benefits) • Items of a personal nature Day 1: Arrival In Mexico / Teotihuacan Register Now Sep Today: Upon arrival at the Mexico City airport we meet with our tour guide who will take us to Teotihuacan to see • Fill out registration form included in this 12 the ancient Pyramids of the sun and the moon. After the visit we proceed to our hotel. brochure. Ask your spiritual director and/or Evening: We check in to our hotel in Mexico City followed by mass and tour coordinator or contact us if you do not dinner. have this form. Day 2: Shrine Of Our Lady Of Guadalupe • Mail your form and non-refundable deposit Sep Today: After breakfast, we go to the Shrine of Our Lady of $300 in check or money order to the of Guadalupe (Patroness of the Americas) where 8 – 10 address at the bottom of the registration 13 million Aztecs converted soon after the Marian apparitions in 1531. -

Holyland Tour

Garabandal, Santiago de Compostela, Fatima, Lourdes & Medjugorje 17 days – Tour 68 Garabandal · Santander · Santiago de Compostela · Lisbon · Santarem (Eucharistic Miracle) · Fatima · Alba de Tormes · Salamanca · Avila (St. Teresa) · Burgos · Loyola (St. Ignatius) · Lourdes · Medjugorje YOUR TRIP INCLUDES: † Centrally located hotels: (or similar) ~ 2 nights: Hotel Santemar in Santander (or Garabandal), Spain ~ 2 nights: San Francisco Hotel Monumento, Santiago De Compostela, Spain ~ 1 night: Marques de Pombal or Mundial, Lisbon, Portugal ~ 2 nights: Santa Maria Jardim, Fatima, Portugal ~ 1 night: Hotel Monterrey, Salamanca, Spain ~ 1 night: Abba, Burgos, Spain ~ 3 nights: Moderne or Chapelle et Parc, Lourdes, France ~ 4 nights: Modern Pansion/Hotel, Medjugorje † Breakfast and Dinner daily † Wine and Mineral Water with Dinners † Transportation by air-conditioned motor coach † Sightseeing and admissions fees as per itinerary † Assistance of Christian guide throughout † Catholic Priest available for Spiritual Direction † Mass daily & Spiritual activities † Visit to Community Cenacolo † Luggage handling (1 piece per person † Flight bag & portfolio of all travel documents 12112019 Day 1 - Arrive Spain - Garabandal (or Santander) Upon arrival in Spain, collect your luggage in the baggage claim area, and continue to the Arrival's Hall, where you will be greeted by a tour escort and/or driver. You will make your way to the bus and transfer to your hotel. As you motor through the scenic countryside of Cantabria, Spain, enjoy the lush green mountains before arriving to the hamlet of Garabandal. Check into your hotel for dinner and an overnight Day 2 - Garabandal After breakfast, start your day visiting Garabandal. Little has changed in this rural town since June 18, 1961 when four children had an apparition first of an Angel, sent to prepare the children for a visit from the Virgin. -

Saint Isaac Jogues Parish

SAINT ISAAC JOGUES PARISH 8149 Golf Road ~ Niles, IL 60714 847/967-1060 ~ Fax # 847/967-1070 Website: http://sij-parish.com The Ascension of the Lord May 24, 2009 Page Two The Ascension of the Lord May 24, 2009 "MAY PILGRIMAGE" The Shrine of Our Lady of Covadonga, Asturias, Spain The Virgin of Covadonga The Sanctuary in the Cave of Covadonga In 1986 the dollar was "strong" and deluxe vacations sixteenth century costume ready to serenade us for a for Americans in Europe were still affordable. Spain few pesetas. Our hotel was the Inn of the Catholic and Portugal were outstanding destinations and real Kings. It was across the plaza from the great shrine values. A priest friend and I had made reservations church. As I glanced back at the shrine, a rose- months before with our travel agent to stay at colored cloud ascended from the pilgrim portal to the pousadas and paradors. Pousadas and paradors are lofty bell towers. It was a "touch" worthy of Franco historic inns, castles, and "four star" hotels in Zeffirelli or C.B. DeMille. Portugal, and Spain. They are always well-located, picturesque, and more than comfortable. In Leaving Santiago for Oviedo and then Asturias, we Estremos, there was actually a bronze plaque that found ourselves in the foothills of the Picos de announced that Vasco da Gama had payed his Europa. High mountain peaks and misty, verdant respects to the Queen of Portugal where we were valleys made it seem more like Switzerland than about to dine and spend the night! Spain. -

View Printable Flyer

Join us on a pilgrimage to September 14 – 27, 2021 $4,949 per person from: Washington (IAD) & Richmond (RIC) Price is Per Person Based on Double Occupancy Spiritual Director: Rev. Dr. Felix Amofa Group coordinator: Jackie Seyfried ( Contact—Phone: 804-304-5063) Optional Post Tour to Rome: Spiritual Director: September 27 - 30, 2021 Rev. Dr. Felix Amofa $1,199 per person in double occupancy To book, visit: www.pilgrimages.com/stgabriel S A M P L E D A Y - BY- D A Y I T I N E R A R Y Day 1, September 14, Tuesday | Depart for Lisbon ing attend the International Pilgrim Mass at the Cathedral of St. James. After Mass there Make your way to your local airport, where you will board your overnight flight(s). Your will be free time for lunch. In the afternoon we will visit the Cathedral of Santiago. meals will be served on board. Formed by Galician granite, this Cathedral is one of the finest architectural examples in Europe as it encompasses Romanesque, Gothic and Baroque styles. Additionally, the Day 2, September 15, Wednesday | Arrive Lisbon Cathedral contains numerous and valuable pieces of art that truly captivate the eye. Upon landing at Lisbon Airport, and after claiming your baggage, proceed to the arri- Upon entering the Cathedral, tradition will lead, as you will hug the dazzling statue of St. val's hall, where you will be greeted by your tour guide and/or driver. This afternoon we James. Following this intimate embrace, you will descent into the crypt where the Pa- will enjoy a panoramic tour of Lisbon.