The Evolution of Bulgogi Over the Past 100 Years*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

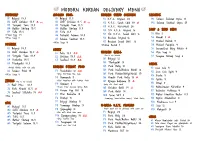

MODERN KOREAN DELIVERY MENU BIBIMBAP AVOCADO BOWL KOREAN FRIED CHICKEN SASHIMI B1 Bulgogi 13.5 A1 Bulgogi 11.5 K1 K.F.C

MODERN KOREAN DELIVERY MENU BIBIMBAP AVOCADO BOWL KOREAN FRIED CHICKEN SASHIMI B1 Bulgogi 13.5 A1 Bulgogi 11.5 K1 K.F.C. Original 24 M1 Salmon Sashimi 10pcs 15 B2 Chili Chicken 13.5 ☆ spicy A2 Chili Chicken 11.5 ☆ spicy K2 K.F.C. Sweet Chili 24 ☆ M2 Salmon Sashimi 20pcs 25 B3 Teriyaki Tuna 13.5 A3 Teriyaki Tuna 11.5 K3 K.F.C. Half&Half 24 B4 Butter Shrimp 13.5 A4 Butter Shrimp 11.5 K4 1/2 K.F.C. Original 16 SOUP & SIDE DISH B5 Tofu 13.5 A5 Tofu 11.5 S1 Rice 2 +Fried Egg 1.5 A6 Teriyaki Salmon 12.5 K5 1/2 K.F.C. Sweet Chili 16 Kimchi 5 ☆ +Miso Soup 4 A7 Salmon Sashimi 13.5 K6 Boneless Original 16 S2 +Miso Soup 4 K7 Boneless Sweet Chili 16 S3 Pickled Radish 3 DOSIRAK +Pickled Radish 3 S4 Pickled Pumpkin 4 D1 Bulgogi 14.5 CURRY S5 Caramelized Baby Potato 4 D2 Chili Chicken 14.5 ☆ C1 Tofu 13.5 ☆☆ KOREAN GRILL S6 Miso Soup 4 -Rice is not included D3 Teriyaki Tuna 14.5 C2 Chicken 13.5 ☆☆ S7 Tomyam Shrimp Soup 6 D4 Donkatsu 14.5 C3 Seafood 14.5 ☆☆ G1 Bulgogi 12 D5 Tteokgalbi 14.5 G2 Tteokgalbi 12 DRINK -Grilled Patties with rice cake KOREAN STREET FOOD G3 Pork Belly 12 R1 Coca Cola 3 D6 Salmon Filet 18 F1 Tteokbokki 12 ☆☆ G4 Pork Neck(Boston Butt) 12 R2 Coca Cola light 3 +Miso Soup 4 -Spicy Stir-fried Rice Cake G5 Pork Platter(Belly&Neck) 13 R3 Fanta 3 F2 Gunmandu 8 G6 Kimchi Pork Belly 13 ☆ -fried Dumplings with Cabbage Salad R4 Sprite 3 JJIGAE -Rice is not included G7 Ojingeo-bokkeum 13 ☆ R5 Stiegl 4 J1 Beef Miso 12.5 F3 Gimmari 8 -Spicy stir fried squid -Korean Fried Seaweed Spring Rolls G8 Chicken Galbi 14 ☆ R6 Kaltenhauser Kellerbier 4 J2 Pork Kimchi 12.5 ☆ F4 Korean Egg Roll 10 R7 Edelweiss Hofbraeu 4 J3 Seafood Silktofu 14 ☆☆ G9 Pork Galbi 14 +Rice 2 F5 Mini Donkatsu 10 G10 Ssam SET 8 R8 Zipfer Limetten Radler 4.5 F6 Gimbap 10 -Ssamjang, Ssam(Lettuce wraps), Sliced Garlic R9 Zipfer Alkoholfrei 4 WOK F7 Bulgogi Gimbap 11 R10 Kloud(korean beer) 4 F8 Tunamayo Gimbap 12 K-GRILL D.I.Y. -

ALL NATURAL BRAISED BEEF CHUCK SHORT RIBS This All Natural Product Continues to Be Popular for Those Who Have a Taste for Decadent Comfort Foods

ALL NATURAL BRAISED BEEF CHUCK SHORT RIBS This all natural product continues to be popular for those who have a taste for decadent comfort foods. Chef's Line® short ribs are braised for 8 hours to achieve the fall-off-the bone result. Now you can serve delicious short ribs without investing the extensive time or labor. Designed and created for chefs with high standards Only ingredients of the highest caliber make their way into our Chef’s Line® products. Designed and created for chefs who insist on the best, Chef’s Line is what you would make if you had the time. Product Inspiration Product Attributes Benefits From gastro-pubs to pop-ups, short ribs are • Choice chuck short rib • All natural finding a place on more and more menus as a • Comes in its own juices; provides • No artificial ingredients great appetizer addition and a traditional approximately three to four portions • Minimally processed favorite entrée. Lightly seasoned with salt • Rectangular in shape • Fully cooked – ready to use and pepper, our all natural short ribs offer • Moist, tender, full-bodied flavor rich flavor without any additives and are a • Braised for 8 hours product of the USA. • Finished product is 75% protein, 25% juice • Product of USA Slowly braised for 8 hours, each portion is • Short rib menu penetration has grown 62% ready to use straight from the bag! We pack over the last 4 years them in their own juices so you can make an au jus reduction that complements any dish. Uses Boost your menu offering by adding a slow cooked taste without the wait. -

Guide to Identifying Meat Cuts

THE GUIDE TO IDENTIFYING MEAT CUTS Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is separated from the bottom round. Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* URMIS # Select Choice Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is Bonelessseparated from 1the480 bottom round. 2295 SometimesURMIS referred # to Selectas: RoundChoic Eyee Pot Roast Boneless 1480 2295 Sometimes referred to as: Round Eye Pot Roast Roast, Braise,Roast, Braise, Cook in LiquidCook in Liquid BEEF Beef Eye of Round Steak Boneless* Beef EyeSame of muscle Round structure Steak as the EyeBoneless* of Round Roast. Same muscleUsually structure cut less than1 as inch the thic Eyek. of Round Roast. URMIS # Select Choice Usually cutBoneless less than1 1inch481 thic 2296k. URMIS #**Marinate before cooking Select Choice Boneless 1481 2296 **Marinate before cooking Grill,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Braise, Cook in Liquid Beef Round Tip Roast Cap-Off Boneless* Grill,** Pan-broil,** Wedge-shaped cut from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Pan-fry,** Braise, VEAL Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless 1526 2341 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Roast, Beef RoundCap Off Roast, Tip RoastBeef Sirloin Cap-Off Tip Roast, Boneless* Wedge-shapedKnuckle Pcuteeled from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Roast, Grill (indirect heat), Braise, Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless Beef Round T1ip526 Steak Cap-Off 234 Boneless*1 Same muscle structure as Tip Roast (cap off), Sometimesbut cutreferred into 1-inch to thicas:k steaks.Ball Tip Roast, Cap Off Roast,URMIS # Beef Sirloin Select Tip ChoicRoast,e Knuckle PBonelesseeled 1535 2350 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Steak, PORK Trimmed Tip Steak, Knuckle Steak, Peeled Roast, Grill (indirect heat), **Marinate before cooking Braise, Cook in Liquid Grill,** Broil,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Stir-fry** Beef Round Tip Steak Cap-Off Boneless* Beef Cubed Steak Same muscleSquare structureor rectangula asr-shaped. -

Authentic Korean Cuisine

SEOUL JUNG AUTHENTIC KOREAN CUISINE SEOUL JUNG KOREA The crossroads of Asia... home of a world renowned cuisine that captures the heart and spirit of its people. With 5,000 years of refinement distilled into a melange of flavors incorporating tradi- tional methods of presentation and seasoning. SEOUL The capital city of Korea, retained its role as the political, eco- nomic and cultural center of the country. Also known as one of the world’s most vibrant city with its rapid economic growth after the Korean-War. It made Seoul known in Asia and worldwide as a model city and an inspiration for countries that they too can achieve aconomic success and prosperity. The world came to know Seoul yet better through the Asian Games(‘86), Olympic Games(‘88), and the FIFA World Cup(‘02). Vestiges of its long history are felt on every corner of this passion- ate and humane city. It certainly is a dynamic city that is constantly re-inventing itself. Experience the cuisine of Korea at Seoul Jung, the flagship restau- rant at the Waikiki Resort Hotel. Featuring traditional Korean dishes with the freshest ingredients, Seoul Jung is the only place in Waikiki where the discriminating traveler can enjoy the best flavors of Seoul. We welcome you to enjoy a taste of the Korean culture and begin your dining adventure with us at Seoul Jung. 감사합니다 Thank you, Mahalo APPETIZERS 육회 YUKHOE ユッケ牛刺し Korean beef tartare served with egg on a bed of Korean pear 20.95 군만두 GUN MANDU 揚げ餃子 Pan-fried dumplings filled with pork and vegetables and served with soy dipping sauce 두부김치 16.50 DUBU KIMCHI 豆腐キムチ Heated tofu with seasoned Kimchi 잡채 18.50 JAPCHAE チャプチェ(韓国春雨) Seasoned glass noodles sautéed with seasoned vegetables 18.50 해물파전 HAEMUL PAJEON 海鮮ねぎチヂミ Shrimp and squid slices with green onions cooked in a light egg batter 19.95 APPETIZERS Above Picture(s) may differ from the original dish. -

Cuisines of Asia

WORLD CULINARY ARTS: Korea Recipes from Savoring the Best of World Flavors: Korea Copyright © 2014 The Culinary Institute of America All Rights Reserved This manual is published and copyrighted by The Culinary Institute of America. Copying, duplicating, selling or otherwise distributing this product is hereby expressly forbidden except by prior written consent of The Culinary Institute of America. SPICY BEEF SOUP YUKKAEJANG Yield: 2 gallons Ingredients Amounts Beef bones 15 lb. Beef, flank, trim, reserve fat 2½ lb. Water 3 gal. Onions, peeled, quartered 2 lb. Ginger, 1/8” slices 2 oz. All-purpose flour ½ cup Scallions, sliced thinly 1 Tbsp. Garlic, minced ½ Tbsp. Korean red pepper paste ½ cup Soybean paste, Korean 1 cup Light soy sauce 1 tsp. Cabbage, green, ¼” wide 4 cups chiffonade, 1” lengths Bean sprouts, cut into 1” lengths 2 cups Sesame oil 1 Tbsp. Kosher salt as needed Ground black pepper as needed Eggs, beaten lightly 4 ea. Method 1. The day prior to cooking, blanch the beef bones. Bring blanched bones and beef to a boil, lower to simmer. Remove beef when it is tender, plunge in cold water for 15 minutes. Pull into 1-inch length strips, refrigerate covered Add onions and ginger, simmer for an additional hour, or until proper flavor is achieved. Strain, cool, and store for following day (save fat skimmed off broth). 4. On the day of service, skim fat off broth - reserve, reheat. 5. Render beef fat, browning slightly. Strain, transfer ¼ cup of fat to stockpot (discard remaining fat), add flour to create roux, and cook for 5 minutes on low heat. -

KIM's KOREAN BBQ A-1. Japchae

KIM’S KOREAN BBQ Haemool 김스 코리언 바베큐 Pa Jeon Pan Seared Mandu 김스 코리언 바베큐 KIM’S APPETIZERSKOREAN BBQ 전식 A-1. Japchae 잡채 Small 7.99 Vermicelli noodles stir fried with Large 10.99 beef & vegetables 만두 A-2. Mandu 6.99 Japchae Ddeobokki Korean style beef & vegetable dumplings (Pan Seared or Fried) A-3. Haemool Pa Jeon 해물 파전 12.99 Korean seafood pancake filled with various seafood & green onions (CONTAINS SHELLFISH) A-4. Ojingeo Twigim 오징어 튀김 14.99 BINGSU 빙수 Korean style fried squid (calamari) Shaved ice dessert with sweet topping. (CONTAINS EGGS) A-5. Ddeobokki 떡볶기 7.99 xx Spicy rice cakes and boiled egg with fish cakes stir-fried in a spicy red pepper sauce Mango Bingsu Patbingsu A-6. Kimchi Jeon 김치 전 12.99 Kimchi pancake made with kimchi, onions, & green onions x Mild Spicy xx Medium Spicy xxx Extra Spicy Strawberry Bingsu Blue-Berry Bingsu ENTREES 정식 김스 코리언 바베큐 KIM’S KOREAN Dak Bulgogi GRILLBBQ 구이 1. Galbisal 갈비살 25.99 Marinated BBQ beef boneless short rib with onions This menu item is available as an optional entrée. You may grill it at the table (two or more orders required) Add Romaine lettuce 1.99 2. Sam Gyeob Sal Gui 삼겹살 구이 19.99 Thick sliced barbeque-style pork belly This menu item is available as an optional entrée. You may grill it at the table (two or more orders required) 3. Bulgogi 불고기 16.99 Marinated grilled shredded beef & onions x Mild김스 Spicy 코리언 xx Medium 바베큐 Spicy xxx KIM’S Extra Spicy (spicy available upon request) KOREAN BBQ This menu item is available as an optional entrée. -

Drums & Flats Breakfast-- CORN DOGS

25-May 26-May 27-May 28-May 29-May 30-May 31-May Venue Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday MEMORIAL DAY Drums & Flats Pulled BBQ Pork Sweet & Sour Chicken Chicken Tampico Baked Chicken Wings Chicken Casserole Pulled BBQ Pork Philly Cheese STEAK Crispy Baked Buffalo Cauliflower Grilled Chicken Philly Cheese Breast Honey Hoison Pork Loin Beef Stroganoff Crispy Chicken Wings Cajun Tilapia Crispy Ranch Chicken CHICKEN Corn on the Cob Garlic Green Beans Fresh Vegetable Medley Fried Chicken Tenders Fried Mushrooms Sautéed Zucchini HOAGIE BUNS Yellow Squash w/ Red Asparagus Fresh Steamed Broccoli Onions Fried Chicken Wings Roasted Cauliflower Orange Basil Carrots HOT WINGS Chopped Cilantro, Green Onions, Broccoli w/ Sundried Baked Beans Egg Rolls Battered Green Beans Sesame Seeds Tomatoes Baked Beans TATER TOTS Potato Wedges Fried Rice Egg Noodles Carrot & Celery Sticks Spicy Potato Wedges Mashed Potatoes Macaroni & Cheese Macaroni & Cheese Yukon Gold Potatoes Jo Jo Potato Wedges Spinach Casserole Honey Dill Carrots Pes w/ Pimentos Steak Fries Golden Rice Baby Carrots Assorted Cakes & Pies Assorted Cakes & Pies Assorted Cakes & Pies Assorted Cakes & Pies Assorted Cakes & Pies Assorted Cakes & Pies Assorted Cakes & Pies Cobbler or Warm Cobbler or Warm Cobbler or Warm Pudding Cobbler or Warm Pudding Cobbler or Warm Pudding Cobbler or Warm Pudding Cobbler or Warm Pudding Pudding Pudding Dinner Roll Dinner Roll Dinner Roll Dinner Roll Dinner Roll Dinner Roll Dinner Roll Corn Bread Corn Bread Corn Bread Corn Bread Corn Bread -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

12 Steak Tartare

November 22nd, 2018 3 Course Menu, $42 per person ( tax & gratuity additional ) ( no substitutions, no teal deals, thanksgiving day menu is a promotional menu ) Salad or Soup (choice, descriptions below) Caesar Salad, Wedge Salad, Lobster Bisque or Italian White Bean & Kale Entrée (choice, descriptions below) Herb Roasted Turkey, Local Flounder, Faroe Island Salmon or Braised Beef Short Rib Dessert (choice) Dark Chocolate Mousse Cake, Old Fashioned Carrot Cake, Pumpkin Cheesecake, Cinnamon Ice Cream, Vanilla Ice Cream or Raspberry Sorbet A LA CARTE MENU APPETIZERS ENTREES Butternut Squash & Gouda Arancini … 13 Herb Roasted Fresh Turkey … 32 (5) risotto arancini, asparagus pesto, truffle oil, mashed potato, herbed chestnut stuffing, fried sage, aged pecorino Romano glazed heirloom carrots, haricot vert, truffled brown gravy, cranberry relish Smoked Salmon Bruschetta … 12 house smoked Faroe Island salmon, lemon aioli, Local Flounder … 32 micro salad with shallot - dill vinaigrette, crispy capers warm orzo, sweet corn, sun dried tomato, edamame & vidalia, sautéed kale, bell pepper-saffron jam, basil pesto Steak Tartare … 14 beef tenderloin, sous vide egg yolk, caper, Faroe Island Salmon* … 32 shallot, lemon emulsion, parmesan dust, garlic loaf toast roasted spaghetti squash, haricot vert & slivered almonds, carrot puree, garlic tomato confit, shallot dill beurre blanc Grilled Spanish Octopus … 14 gigante bean & arugula sauté, grape tomatoes, Boneless Beef Short Rib … 32 salsa verde, aged balsamic reduction oyster mushroom risotto, sautéed -

Nine Food Essentials Found in Meat

MEAT NUTRITION • BUYING * COOKING Nine Food Essentials found in Meat 1. Protein — builds and repairs body tissues. 2. Iron—prevents anemia. 3. Copper—helps body use iron. 4. Phosphorus — builds strong bones and teeth; regulates the body; needed for body tissues. 5. Fat — produces heat and en- ergy; carries certain important vitamins. 6. Vitamin A—promotes growth; increases body resistance. 7. Vitamin B Complex (Thiamin) — stimulates appetite; pro- motes growth'; prevents and cures beriberi; is necessary for utilization'of carbohydrate. 8. Vitamin B Complex (Ribo- flavin) — promotes growth; protects against certain ner- vous disorders and liver disturbances. 9. Vitamin B Complex (Nico- tinic Acid) — prevents and cures pellagra. Published by NATIONAL LIVE STOCK AND MEAT BOARD •10? South Dearborn Street CHICAGO. ILLINOIS These Charts Will Help You in the Selection and Preparation of Meat BEEF CHART PORK CHART LAMB CHART VEAL CHART FIRST SELECT YOUR MEAT CUT, THEN OTHER FOODS — BALANCED MEALS BUILD HEALTH MENUS WITH BEEF MENUS WITH PORK MENUS WITH LAMB MENUS WITH VEAL • ROAST BEEF *»->* Escalloped Potatoes, Julienne Carrots, Apple and ROAST PORK Baked Potatoes, Escalloped Tomatoes, Baked © LEG OF LAMB Brown Potatoes, Green Beans, Orange and Mint © VEAL ROAST *«•-> Mashed Potatoes, Green Beans, Stuffed Tomato Celery Salad, Cherry Pie. Apple in Gelatine, Pineapple Sherbet and Cookies. Salad, Cocoanut Custard Pie. Salad, Apple Pie. © POT-ROAST Browned Potatoes, Green Beans, Mexican Slaw, © BAKED HAM Candied Sweet Potatoes, Green Beans, Pineapple © BROILED CHOPS Shoestring Potatoes, Peas, Combination Salad, • CHOPS OR STEAK Riced Potatoes, Broccoli, Apple and Celery Fresh Fruit. and Celery Salad, Lemon Pie. Devil's Food Cake. -

List of the Restaurant 28 No

List of the Restaurant 28 No. Name 26 1 Cheonhyangwon (천향원) 27 22 2 Jungmun beach kaokao (중문비치 카오카오) 23 24 3 Hansushi (한스시) 25 Cheonjeyeon-ro Daegijeong (대기정) 14 4 Jungmun-ro 5 Jusangjeolli Hoekuksu (주상절리회국수) 20 13 Yeomiji Botanic garden Jungmunsang-ro 6 Gerinjeong (그린정) Jungmun elementary school 21 7 Cheonjeyeon (천제연식당) Jungmungwangwang-ro 1 15 16 33 Jungmunhaenyeon`s house (중문해녀의집) 19 8 18 17 Cheonjeyeon-ro Jejudolhareubangmilmyeon 11 3 9 (제주돌하르방밀면) Cheonjeyeon Waterfall Korean dry sauna 10 Karamdolsotbap (가람돌솥밥) Cheonjeyeon Temple 9 Jungmun high school 11 Hanarogukbap (하나로국밥) 10 Gwangmyeong Temple 32 12 Galchi Myungga (갈치명가횟집) Jungmungwangwang-ro 13 Misjejukaden (미스제주가든) 14 Jungmundaedaelbo (중문대들보) 6 15 Kuksubada (국수바다) Daepo-ro 31 16 Kyochon Chicken (교촌치킨) 17 Dasoni (다소니) 18 Sundaegol (순대골) 29 19 Pelicana Chicken (페리카나치킨) 20 Tamnaheukdwaeji (탐나흑돼지) 30 2 Jungmungwangwang-ro 21 Jangsuhaejangguk (장수해장국) 22 Eoboonongboo (어부와농부) 7 Jungmungwangwang-ro Daepojungang-ro 23 Madangkipeunjip (마당깊은집) 8 24 Jejumihyang (제주미향) ICC JEJU 25 Chakhanjeonbok (착한전복) 29 Halmenisonmark (할머니손맛) Ieodo-ro 4 Daepo-ro 27 OhSungsikdang (오성식당) 28 Cheonjeyeon (천제연토속음식점) 12 29 Badajeongwon (바다정원) 30 Seafood Shangri-la (씨푸드 샹그릴라) Ieodo-ro 5 31 Papersoup (페이퍼숲) 32 Han`s family (한스패밀리) 33 Beokeonara (버거나라중문점) Korean restaurant Japanese restaurant Chinese restaurant Western restaurant The 20th World Congress of Soil Science June 8(Sun) ~ 13(Fri), 2014, ICC Jeju, Jeju, Korea Restaurant Information Distance No. Name Type Menu Price Tel (by car) Jajangmyeon (Noodles with black soybean sauce), Jjamppong (Spicy seafood noodle soup), Tangsuyuk Cheonhyangwon (천향원) Chinese restaurant 9 min. KRW 4,500~40,000 1 (Sweet and sour pork) 82-64-738-5255 2 Jungmun beach kaokao (중문비치 카오카오) Chinese restaurant 9 min. -

Buldaegi Bbq House

BULDAEGI BBQ HOUSE TABLE GRILL Beverages Bottled Water — $2 Sparkling Water — $2.50 Hot Tea (Green or Earl Gray)— $1.75 Canned Soda — $1.75 Sweet or Unsweet Tea (2 refills) — $2.25 DOMESTIC BEER — $4 Yuengling Blue Moon IMPORTED BEER — $5 Tsingtao (China) Heineken (Holland) Asahi (Japan) Kirin Ichiban (Japan) Sapporo (Japan) OB (Korea) Fried Dumplings (튀김만두) — $8 Deep fried dumplings with chicken and vegetables. 8 pieces. Haemul Pancake (해물파전) — $16 Crispy pancake withAppetizers assorted seafood, carrot, green and white onion. House Japchae (불돼지잡채) — $14 Glass noodles, carrot, white and green onion. Choose a style: Pork, Beef, or Veggie. Duk Bok Ki* (떡볶기) — $14 Rice cake, fish cake, hard-boiled egg, hot pepper paste sauce.Spicy. Dak Gangjeong (닭강정) — $14 Crispy boneless fried chicken glazed with sweet, housemade sauce. Tang Su Yuk (탕수육) — $18 Deep fried meat or tofu in housemade sweet & sour sauce. Choose a style: Beef, Pork, or Tofu. Spring Rolls - $8 Shredded cabbage, carrots, tofu, onions. 6 pieces. *Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish, or egg may increase your risk of food-borne illnesses. Choose a minimum of 2 BBQ orders or 1 Combo. Includes lettuce wraps, banchan, corn cheese, steamed egg*. Extra small sidesTable — $6 each. (SeeGrill back page for options) Pork Combo A — $50.50 Choose any 5 meats from Pork BBQ. Serves 2. Pork Combo B — $70.50 Choose any 7 meats from Pork BBQ. Serves 3-4. Beef Combo A — $65.50 Choose 2 Beef BBQ and 2 Premium Beef BBQ. Serves 2. Beef Combo B — $89.50 Choose 2 Beef BBQ and 3 Premium Beef BBQ.