Killer Incentives: Relative Position, Performance and Risk-Taking Among German Fighter Pilots, 1939-45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deutsche Radio-Nachrichten: Der Wandel Ihres Sprachgebrauchs 1932 – 2001

1 Deutsche Radio-Nachrichten: Der Wandel ihres Sprachgebrauchs 1932 – 2001 vorgelegt von MA Sven Scherz-Schade Von der Fakultät I – Geisteswissenschaften Der Technischen Universität Berlin Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie - Dr. phil. - genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Nobert Bolz Berichterin: Prof. Dr. Sabine Kowal Berichter: Prof. Dr. Roland Posner Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 22.09.2004 Berlin 2004 D 83 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis I. Einleitung ……………………………………………………………………………6 II. Theoretische Grundlagen: Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit in Radio- Nachrichten ………………………………………………………………………..18 A. Textsorte Radio-Nachrichten ……………………………………………………18 B. Medium und Konzeption ………………………………………………………….25 1. Historische Ebene: Diskurstraditionen ………………………………………..31 2. Äußerungsebene ………………………………………………………………. 34 3. Universale Ebene ……………………………………………………………….35 C. Rekontextualisiserung ……………………………………………………………37 D. Wandel im Sptrachgebrauch und diskurstraditionelle Verschiebung……38 E. Sprachnormen ……………………………………………………………………...40 F. Medientrasfer ……………………………………………………………………….42 G. Quellenlage …………………………………………………………………………43 III. Radiohistorische Betrachtung ………………………………………………….47 A. Nachrichten im Rundfunk der Weimarer Zeit …………………………………47 1. Radiohistorischer Zusammenhang ……………………………………………47 2. Reflexionen über Radio- und Nachrichtensprache ………………………….50 B. Radio-Nachrichten im Nationalsozialismus …………………………………..55 1. Radiohistorischer Zusaammenhang ………………………………………….55 2. Reflexionen über -

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631 Call# Title Author Subject 000.1 WARBIRD MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD EDITORS OF AIR COMBAT MAG WAR MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD IN MAGAZINE FORM 000.10 FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM, THE THE FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM YEOVIL, ENGLAND 000.11 GUIDE TO OVER 900 AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS USA & BLAUGHER, MICHAEL A. EDITOR GUIDE TO AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS CANADA 24TH EDITION 000.2 Museum and Display Aircraft of the World Muth, Stephen Museums 000.3 AIRCRAFT ENGINES IN MUSEUMS AROUND THE US SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIST OF MUSEUMS THROUGH OUT THE WORLD WORLD AND PLANES IN THEIR COLLECTION OUT OF DATE 000.4 GREAT AIRCRAFT COLLECTIONS OF THE WORLD OGDEN, BOB MUSEUMS 000.5 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE LIST OF COLLECTIONS LOCATION AND AIRPLANES IN THE COLLECTIONS SOMEWHAT DATED 000.6 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE AVIATION MUSEUMS WORLD WIDE 000.7 NORTH AMERICAN AIRCRAFT MUSEUM GUIDE STONE, RONALD B. LIST AND INFORMATION FOR AVIATION MUSEUMS 000.8 AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUMS OF AMERICA ALLEN, JON L. LISTS AVATION MUSEUMS IN THE US OUT OF DATE 000.9 MUSEUM AND DISPLAY AIRCRAFT OF THE UNITED ORRISS, BRUCE WM. GUIDE TO US AVIATION MUSEUM SOME STATES GOOD PHOTOS MUSEUMS 001.1L MILESTONES OF AVIATION GREENWOOD, JOHN T. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN AIRCRAFT 001.2.1 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE BRYAN, C.D.B. NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM COLLECTION 001.2.2 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE, SECOND BRYAN,C.D.B. MUSEUM AVIATION HISTORY REFERENCE EDITION Page 1 Call# Title Author Subject 001.3 ON MINIATURE WINGS MODEL AIRCRAFT OF THE DIETZ, THOMAS J. -

One of the Enjoyable Aspects of Pilot Counters to Give Missions Historical

One of the enjoyable aspects of Galland, Adolph wanted more bombers; where RISE OF THE LUFTWAFFE and (Bf.109: P, H, Bu, A; Me.262: A, CV, P, Bu) Galland wanted to create a central EIGHTH AIR FORCE is using One of the most famous of all the fighter defense for protecting pilot counters to give missions Luftwaffe pilots, Adolph Galland Germany from Allied bombers, historical color. To many players, was a product of the "secret" Goring wanted a peripheral one. defeating a named ace is an event Luftwaffe of the 1930's, flying his Towards the end of the war worth celebrating. However, first combat missions over Spain Galland would repeatedly con while some of the pilots included in 1937 and 1938. He started serve his meager fighter forces for in the games are familiar to flying up to four sorties a day in telling blows upon the Allies, anyone with a passing interest in WW II in an antiquated Hs.123 only to have Hitler order them World War II (e.g. Bader, Galland, ground support aircraft during into premature and ineffective Yeager), most are much less the invasion of Poland, earning offensives. Galland also had to known. This is the first in a series the Iron Cross, Second Class. defend the pilots under his of articles by myself and other Without a victory at the end of the command from repeated defama authors which provide back campaign, he used trickery and a tion at the hands of Hitler, Goring ground information on the pilots sympathetic doctor to get himself and the German propaganda of the Down in Flames series. -

Penttinen, Iver O

Penttinen, Iver O. This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on October 31, 2018. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard First revision by Patrizia Nava, CA. 2018-10-18. Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Penttinen, Iver O. Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Sketch ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Image -

Erich Hartmann " Erich Hartmann, the Poetry of Daily Life " March 21 - May 4Th 2019

Catherine & André Hug present : Carte blanche à CLAIRbyKahnGallery Erich Hartmann " Erich Hartmann, the Poetry of Daily Life " March 21 - May 4th 2019 Galerie Catherine et André Hug 40, rue de Seine / 2, rue de l’Échaudé 75006 Paris www.galeriehug.com Mardi au samedi : 11h à 13h et 14h30 à 19h The Kiss,©ErichHartmann/MagnumPhotos/CLAIRbyKahn The Erich Hartmann, The Poetry of Daily Life exhibition emerged from a chance meeting and an immediate enchantment. The meeting was between Anna-Patricia Kahn, who is the director of CLAIRbyKahn, and Catherine and André Hug, who are the renowned owners of their eponymous gallery in Paris. And the enchantment took place the instant Catherine and André were shown the Erich Hartmann oeuvre. Then and there, they decided to give a "carte blanche" for a Hartmann show to CLAIRbyKahn, the gallery which represents the photographer’s archives. Hartmann (b. 1922 in Munich, d. 1999 in New York) is celebrated for the subtle, mysterious poetry that emanates from his photography, the play of shadow and light that is captivating yet respectful. He embraced places, objects, and people with his camera, never unsettling the moment, always capturing it in a way that allowed it to be rediscovered. The Poetry of Daily Life exhibition features 27 images by Hartmann that magnify the glory of the ordinary and the dignity of the routine. The photographs on display are all vintage prints that have the unique quality of being developed by Hartmann’s own hand. This will be a momentous year for the Erich Hartmann archives as there will also be two major museum exhibitions consecrated to the legendary photographer: in Bale, Switzerland from February to July 2019 as part of a collective exhibition Isrealities; and then in November 2019, his Irish portfolio will be exhibited at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin. -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy. -

5Fc5fa615ae94f5ef7c7f4f4 Bofb

Contemporary Accounts 85 Sqn Contemporary Accounts 1 Sqn 1 September 1940 - 10.45 - 11.30 hrs Combat A. attack on Tilbury Docks. 1 September 1940 - 10.45 - 11.30 hrs Combat A. attack on Tilbury Docks. 85 SQUADRON INTELLIGENCE REPORT 1 SQUADRON OPERATIONS RECORD BOOK 12 Hurricanes took off Croydon 11.05 hours to patrol base then vectored on course 110 degrees to Nine Hurricanes led by F/Lt Hillcoat encountered a formation of Me109s protecting enemy bombers Hawkinge area to intercept Raid 23. east of Tonbridge. The fighters were attacked and in the ensuing dog fight four Me109s were destroyed 9 Me109s were sighted at 11.30 hours flying at 17,000 feet believed to be attacking Dover balloons. by F/Lt Hillcoat, P/Os Boot, Birch and Chetham. Our casualties nil. It was noticed that these e/a all had white circles around the black crosses. 12 aircraft landed at Croydon between 11.58 and 12.30 hours. COMBAT REPORT: COMBAT REPORT: P/O P V Boot - Yellow 2, A Flight, 1 Squadron P/O G Allard - A Flight, 85 Squadron I was Yellow 2. Yellow Section split up to avoid attack from the rear by Me109s. I As Hydro Leader the squadron was ordered to patrol base and then vectored to advance climbed to attack some Me109s who were circling with other e/a. When at 15,000 feet base angels 15. When in position I saw e/a on my right. So I climbed a thousand feet above and one Me109 came from the circle with a small trail of white smoke. -

Werner Mölders Geb

Oberst Werner Mölders geb. 18.03.1913 Gelsenkirchen gest. 22.11.1941 Breslau-Gandau General der Jagdflieger RK 29.05.1940 Hauptmann 002.EL 21.09.1940 Major 002.S 22.06.1941 Oberstleutnant 001.B 15.07.1941 Oberst Luftwaffe Auszeichnungen Beförderungen erster Jagdflieger mit dem Ritterkreuz 1932 Fahnenjunker EK II am 27.09.1939 1933 Fähnrich EK I am 03.04.1940 1934 Oberfähnrich Spanienkreuz mit Schwertern in Gold mit Brillanten 1934 Leutnant Flugzeugführer-Beobachterabzeichen in Gold mit Brillanten 1936 Oberleutnant Frontflugspange für Tagjäger in Gold mit Brillanten 1939 Hauptmann zehnmalige Nennung im Wehrmachtsbericht 1941 1940 Major Verwundetenabzeichen in Schwarz 1940 Oberstleutnant Dienstauszeichnung IV. Klasse 1941 Oberst Spanische Medalla Militar Spanische Medalla de la Campana Am 15. Juli 1941 ging Oberstleutnant Werner Mölders in die Luftkriegsgeschichte ein, als er als erster Jagdflieger seinen 100. bestätigten Luftsieg erzielte. Am nächsten Tag erhielt er als erster Soldat der Wehrmacht die Brillanten zum Ritterkreuz mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern verliehen. Weil er dadurch für die Luftwaffenführung unersetzbar geworden war, wurde er Ende Juli mit einem strengen Feindflugverbot belegt. Mölders wurde dann mit 28 Jahren zum jüngsten Oberst der Luftwaffe befördert und im September zum ersten General der Jagdflieger ernannt. Diese neu geschaffene Dienststelle sollte den jungen Frontpiloten einen näheren Bezugspunkt zur Führung geben. Als am 17. Novemver 1941 Generalfeldzeugmeister Ernst Udet Selbstmord beging, wurde Mölders nach Berlin befohlen und sollte dort mit anderen hochdekorierten Fliegern wie Galland, Oesau und Lützow die Ehrenwache halten. Doch auf dem Flug von Cherson über Lemberg nach Berlin geschah das Unglück. Die He-111, mit der Mölders nach Berlin geflogen werden sollte, streifte bei schlechtem Wetter in Breslau einen hohen Fabriksschornstein und stürzte ab. -

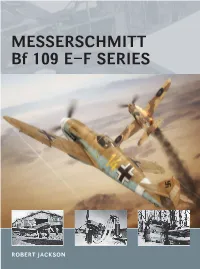

Messerschmitt Bf 109 E–F Series

MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON 19/06/2015 12:23 Key MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109E-3 1. Three-blade VDM variable pitch propeller G 2. Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine, 12-cylinder inverted-Vee, 1,150hp 3. Exhaust 4. Engine mounting frame 5. Outwards-retracting main undercarriage ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND ILLUSTRATOR 6. Two 20mm cannon, one in each wing 7. Automatic leading edge slats ROBERT JACKSON is a full-time writer and lecturer, mainly on 8. Wing structure: All metal, single main spar, stressed skin covering aerospace and defense issues, and was the defense correspondent 9. Split flaps for North of England Newspapers. He is the author of more than 10. All-metal strut-braced tail unit 60 books on aviation and military subjects, including operational 11. All-metal monocoque fuselage histories on famous aircraft such as the Mustang, Spitfire and 12. Radio mast Canberra. A former pilot and navigation instructor, he was a 13. 8mm pilot armour plating squadron leader in the RAF Volunteer Reserve. 14. Cockpit canopy hinged to open to starboard 11 15. Staggered pair of 7.92mm MG17 machine guns firing through 12 propeller ADAM TOOBY is an internationally renowned digital aviation artist and illustrator. His work can be found in publications worldwide and as box art for model aircraft kits. He also runs a successful 14 13 illustration studio and aviation prints business 15 10 1 9 8 4 2 3 6 7 5 AVG_23 Inner.v2.indd 1 22/06/2015 09:47 AIR VANGUARD 23 MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON AVG_23_Messerschmitt_Bf_109.layout.v11.indd 1 23/06/2015 09:54 This electronic edition published 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Osprey Publishing, PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA E-mail: [email protected] Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc © 2015 Osprey Publishing Ltd. -

Barrett Tillman

IN AThe killsDAY and claims ACE of the top shooters BY BARRETT TILLMAN n the morning of April 7, 1943, American Great War air warriors fi ghter pilots on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Probably the fi rst ace in a day was Austro-Hungarian Stabsfeld- Islands responded to a red alert. More than webel Julius Arigi. On August 22, 1916, with his gunner 100 Japanese aircraft were inbound, sending Feldwebel Johann Lassi, he intercepted Italian aircraft over Wildcats and P-40s scrambling to inter- Albania’s Adriatic coast. The Austrians cept. In a prolonged combat, the de- downed fi ve Farman two-seaters, fenders claimed 39 victories and actu- destroyed or abandoned on the ally got 29—a better than normal ratio water. However, a single-seater of actual kills versus claims. The belle pilot contributed to two of the Oof the brawl was 1st Lt. James E. Swett, a 22-year-old victories. Arigi ended the war as Marine entering his fi rst combat. Fifteen minutes later, Austria’s second-ranking ace with he was fi shed out of the bay, having ditched his shot-up 32 victories. F4F-4 perforated by Japanese and American gunfi re. Almost certainly, the fi rst pilot downing fi ve opponents unaided in one day occurred during April 1917. Though wearing glasses, Leutnant Fritz Otto Bernert became a fi ghter pilot. During “Bloody April” he was on a roll, accounting for 15 of Jasta Boelcke’s 21 victories. On the 24th, the day after receiving the Pour le Merite, he led an Alba- tros patrol. -

Luftwaffe Eagle Johannes Steinhoff Flying with Skill and Daring, the Great Ace Survived the War and a Horrible Accident, Living Into His 80S

Luftwaffe Eagle Johannes Steinhoff Flying with skill and daring, the great ace survived the war and a horrible accident, living into his 80s. This article was written by Colin D. Heaton originally published in World War II Magazine in February 2000. Colin D. Heaton is currently working on a biography of Johannes Steinhoff with the help of the great ace's family. Johannes Steinhoff was truly one of the most charmed fighter pilots in the Luftwaffe. His exploits became legendary though his wartime career ended tragically. Steinhoff served in combat from the first days of the war through April 1945. He flew more than 900 missions and engaged in aerial combat in over 200 sorties, operating from the Western and Eastern fronts, as well as in the Mediterranean theater. Victor over 176 opponents, Steinhoff was himself shot down a dozen times and wounded once. Yet he always emerged from his crippled and destroyed aircraft in high spirits. He opted to ride his aircraft down on nearly every occasion, never trusting parachutes. Steinhoff lived through lengthy exposure to combat, loss of friends and comrades, the reversal of fortune as the tide turned against Germany, and political dramas that would have broken the strongest of men. Pilots such as Steinhoff, Hannes Trautloft, Adolf Galland and many others fought not only Allied aviators but also their own corrupt leadership, which was willing to sacrifice Germany's best and bravest to further personal and political agendas. In both arenas, they fought a war of survival. Aces like Steinhoff risked death every day to defend their nation and, by voicing their opposition to the unbelievable decisions of the Third Reich high command, risked their careers and even their lives. -

Bluff Mit Einer „Siegreichen Gegen Offensive" an Der Mittleren Front

NACHRICHTENBLATT DER LANDESBAUERN. SCHAFT, DEUTSCHEN ARBEITSFRONT UND DER KDSLINER STAATLICHEN UND STÄDTISCHEN BEHÖRDEN PARTEIAMTLICHE ZEITUNG DER NSDAP., GAU POMMERN ZEITUNG Jahrgang 1942 Sonnabend Sonntag, 29./30. August Nr. 238/239 Tatsache ist, daß die Sowjets in wochenlangen Kämpfen Zehntausende sinnlos geopfert, aber nichts erreicht haben Moskau ändert dieTaktik: Bluff mit einer „siegreichen Gegen offensive" an der mittleren Front Ein törichter Versuch, durch Lügenmeldungen den im Süden dem deutschen Angriff weichenden Truppen Mut zu machen Eigener Bericht der pommerschen Gaupresse Stettin, 29. August. Plötzlich hat Moskau, das die Lage seit Wochen nur in rchwärzestem Pessimismus dargestellt hat, die Taktik geändert und be ^Lenin- • Tichwin richtet von „großen Erfolgen west grad * Nowgorod Der Befehl zum Sturmangriff ist durchgegeben. Das Gewehr schußbereit, nahmen unsere lich und nordwestlich von Mos- Ä V\)H, tapferen Infanteristen die Höhe im Sturm fi-PK.-Photo: Kriegsberichter Augustin k a u“, wo eine Gegenoffensive der Bolsche fii/Aus s • e waidar Hohen wisten seit einiger Zeit bereits in Gang ge kommen sei und zu den „ersten entscheiden Die Seeschlacht noch nicht abgeschlossen den Vorstößen“ geführt habe. Gleichzeitig wird der Ernst der Situation *Der Kampf kann jeden Augenblick von neuem beginnen” - Die Bedrohung von Port im Kaukasus und im Raume von Stalingrad Moresby - Tokio: „Je ungeduldiger der Feind wird, um so wuchtiger treffen wir ihn” erneut unterstrichen. Man gewinnt den Ein druck, daß Stalin die erlogenen Siegesberichte Drahtbericht unseres Korrespondenten Salomoninseln Abstand nehmen werde. Die von der mittleren Front verbreiten läßt, um Stockholm, 29. August. Amerikaner könnten nicht ohne weiteres die den an der Südfront verzweifelt kämpfenden USA.-Truppen, die dort gelandet sind, de».'Ja Armeen neuen Mut einzuflößen.