The Specialness of Special Libraries | Pages 1 - 45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

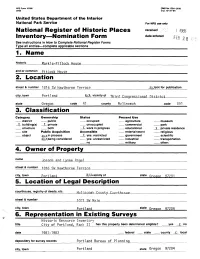

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received r3 ! I985 Inventory—Nomination Form oawemereudate entered FEB ? £« \j See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections____________________________________ 1. Name historic Markle-Pittock House and or common pjttock House 2. Location street & number 1816 SW Hawthorne Terrace for publication city, town Portland state Oregon code 41 county Multnomah code 051 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both _ X_ work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object -j^t£ in process _ X_ yes: restricted government scientific 4^, being considered _ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name and I ynne Angel street & number 1fl16 S y Havithnrne Tprrar.e city, town Portland JL/Avicinity of state QreaQn 07201 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Multnornah County Courthosue street & number m?1 SW Main city, town Portland state Qreaon 972Q4 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Historic Resource Inventory title City Of Portland, Rank II has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date 1981-1983 federal state county local depository for survey records Portland Bureau of Planning__ city, town Portland state Oregon 97204 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered _X_ original site -Xgood ruins _X_ altered moved date N/A fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Markle-Pittock House, whose construction was begun in 1888, was once considered the largest and most prominently sited residence in the city. -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York. -

Northwest Trails Newsletter of the Northwest Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association

Northwest Trails Newsletter of the Northwest Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association Volume 32, No. 3 Summer 2017 NW OCTA Annual Fall Picnic Saturday, September 23, 9:00 a.m. – 3:00 p.m. Clark County Genealogical Society Annex 715 Grand Blvd., Vancouver, Washington The chapter’s annual fall event will again be held this year at the Clark County Genealogical Society Annex in Vancouver, WA. The event will begin at 9:00 a.m. with a coffee hour, and the meeting will begin at 10:00. We will include a chapter meeting, a recap of this year’s events, and discussion of other important issues for the coming year. Pre-registration is not necessary. Be prepared to pay $10 at the door to cover space rental and other picnic expenses. Bring your own picnic lunch. This is not a potluck. Bring a dessert for the dessert table. The chapter will furnish coffee and tea. Soft drinks will be available for a small donation. Raffle and Silent Auction. Please bring items you think would make good raffle or silent auction contribution. Please bundle magazines into sets of at least a year. Program Highlights: Shirlee Evans, member and author, will explain her two new historical fiction books—Their Troubled Trails and No Belonging Place—and have copies for sale. After lunch, there will be reports by the different committee leaders. Other board issues will be discussed. Directions and parking: From I-5. Take exit 1-C (Mill Plain Exit) and drive east on Mill Plain about 1.5 miles to Grand Blvd. -

Northwest Trails, Spring 2015 1

NNoorrtthhww eesstt TTrraaiillss Newsletter of the Northwest Chapter of the Oregon-California Trails Association Volume 30, No. 2 Spring 2015 Base O’ Blue Mountains Oregon Trail Symposium Red Lion Hotel Pendleton, Oregon July 25–26, 2015 You are invited to attend NWOCTA’s Base O’ Blue Mountains Oregon Trail Symposium July 25–26 at the Red Lion Hotel, Pendleton, Oregon. The Symposium will feature the history of exploration and migration out of the Blue Mountains. Events will include a day of presentations on Saturday, culminating with a bus tour of Frenchtown and Whitman Mission National Historic Site on Sunday. The full two-day registration fee of $100 per person includes a buffet lunch on Saturday and the Sunday bus tour and box lunch. (See the registration form for partial registration rates.) The Red lion is offering the special rate of $89 per night for Friday, July 24, and Saturday July 25. Be sure to make your registrations with the Red Lion by July 3 to take advantage of the reduced rate. Presentations Dennis Larsen and Karen Johnson, ”Edward Jay Allen and the Opening of Naches Pass” Ray Egan, “On the Trail of a Legend” David J. Welch, ”Trail Routes from the Blues to the Whitman Mission and the Columbia River” Sam Pambrun, ”Frenchtown and Its Inhabitants” Bonnie Sager, ”Marie Dorion” Roger Blair, “Walter Meacham, President Harding, and the 1923 Oregon Trail Pageant” Registration Form is on page 9 Northwest Trails, Spring 2015 1 NW Chapter Directory Pioneer Mothers Memorial Cabin President Jim Tompkins 503-880-8507 [email protected] Vice President Rich Herman 360-576-5139 [email protected] Secretary Polly Jackson [email protected] Treasurer Glenn Harrison 541-926-4680 [email protected] Pioneer Mothers Memorial Cabin. -

Places to Visit in Oregon

25+ Places to Visit in Oregon http://www.oregonlive.com/northwest-life/index.ssf/oregon-travel/25-places-to-explore-in-oregon.html Whether you live here or are just visiting, you may find yourself overwhelmed by the options. With that in mind -- and in celebration of the state's 150th birthday - Ultimate Northwest created our own "bucket list" for Oregon. On the following pages, you'll find 150 of our favorite getaways, from the iconic to the off- beat. Yes, it's an arbitrary list (and it might miss one or two of your favorites), so consider it a starting point. In fact, we challenge you to get out there and get to know our incredible state by creating your own 150 - in celebration of Oregon. #1 Buy fresh organics at the farm stand #5. Hood River's Fruit Loop series of events includes special at Gathering Together Farm (25159 (hoodriverfruitloop.com) is one of tastings, open houses and vineyard Grange Hall Road, Philomath; 541-929- those iconic Oregon destinations, like seminars, and takes place between 4270; gatheringtogetherfarm.com). Dur- Crater Lake and Multnomah Falls -- a mid-February and Labor Day ing the growing season, the Community can't-miss experience. Wedged be- weekend in all agricultural viticul- Supported Agriculture farm also serves tween the foothills of Mount Hood ture areas. fresh organic lunch, Saturday breakfast and the mighty Columbia River, this and, on the first and third Sundays of fertile valley was planted by hopeful the month, a knockout brunch. pioneers more than 150 years ago. #8. While pinot noir is the star of the Willamette Valley, southern #2. -

Oregon Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines: a Whig Appointee in a Democratic Territory

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-7-1996 Oregon Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines: A Whig Appointee in a Democratic Territory Katherine Louise Huit Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Huit, Katherine Louise, "Oregon Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines: A Whig Appointee in a Democratic Territory" (1996). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5293. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7166 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Katherine Louise Huit for the Master of Arts in History were presented May 7, 1996, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITIEE APPROVALS: Tom Biolsi Re~entative of ;e Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: David John.Sor}{ Chair Department-of History AA*AAAAAAAAAAAAA****AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA**********AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY on za-/4?£ /<f9t;, ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Katherine Louise Huit for the Master of Arts in History presented May 7, 1996. Title: Oregon Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines: A Whig Appointee In A Democratic Territory. In 1846 negotiations between Great Britain and the United States resulted in the end of the Joint Occupancy Agreement and the Pacific Northwest became the property of the United States. -

Oregon Historic Properties Crossword Puzzle

Oregon Historic Properties Crossword Check out these great facts about a few of our wonderful historic properties in Oregon, then visit their websites to learn more! 1M 2W 3H 4T A L L O W 5M 6W I L L A M E T T E N O L I 7C T U L R 8O R E G O N C I T Y I I T A 9P N T M 10P I H H H 11L T T O C I A T 12R O S E O H L N O S D R 13P A I N E 14S 15C A R O U S E L I L P 16C K K S O O I 17G 18G T W F V N 19C I O M O E N A 20L O R D A N D S C H R Y V E R N B D S T E R 21F A E O E D ' 22C A R D E R N K R S T A T N B H H I R B E H 23O R E G O N I A N I 24P U G H R O U H D T U S T G T S E O 25R U G B E A T E R 26C A R N E G I E N S Created using the Crossword Maker on TheTeachersCorner.net Across Down 4. Ingredient for pioneer soap and for making 1. This family built the first frame house in Albany, candles. -

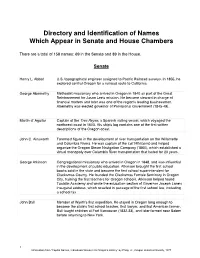

Inscribed Names in the Senate and House Chambers

Directory and Identification of Names Which Appear in Senate and House Chambers There are a total of 158 names: 69 in the Senate and 89 in the House. Senate Henry L. Abbot U.S. topographical engineer assigned to Pacific Railroad surveys. In 1855, he explored central Oregon for a railroad route to California. George Abernethy Methodist missionary who arrived in Oregon in 1840 as part of the Great Reinforcement for Jason Lee's mission. He became steward in charge of financial matters and later was one of the region's leading businessmen. Abernethy was elected governor of Provisional Government (1845-49). Martin d’ Aguilar Captain of the Tres Reyes, a Spanish sailing vessel, which voyaged the northwest coast in 1603. His ship's log contains one of the first written descriptions of the Oregon coast. John C. Ainsworth Foremost figure in the development of river transportation on the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. He was captain of the Lot Whitcomb and helped organize the Oregon Steam Navigation Company (1860), which established a virtual monopoly over Columbia River transportation that lasted for 20 years. George Atkinson Congregational missionary who arrived in Oregon in 1848, and was influential in the development of public education. Atkinson brought the first school books sold in the state and became the first school superintendent for Clackamas County. He founded the Clackamas Female Seminary in Oregon City, training the first teachers for Oregon schools. Atkinson helped found Tualatin Academy and wrote the education section of Governor Joseph Lane's inaugural address, which resulted in passage of the first school law, including a school tax. -

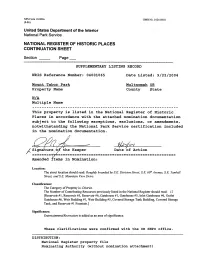

This Property Is Listed in the National Register of Historic Places In

NFS Form 10-900a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section ___ Page __ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 04001065 Date Listed: 9/22/2004 Mount Tabor Park Multnomah OR Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. '——' f / / r I 7 / Signature /or the Keeper Date of Action — — — — = = — — _/L^_ _____ ______ = = _______ = ____ = ___ = _____.__ = = _______ = ___: _ Amended Items in Nomination: Location: The street location should read: Roughly bounded by S.E. Division Street, S.E. 60th Avenue, S.E. Yamhill Street, and S.E. Mountain View Drive. Classification: The Category of Property is: District. The Number of Contributing Resources previously listed in the National Register should read: 12 [Reservoir #1, Reservoir #5, Reservoir #6, Gatehouse #1, Gatehouse #5, Inlet Gatehouse #6, Outlet Gatehouse #6, Weir Building #1, Weir Building #5, Covered Storage Tank Building, Covered Storage Tank, and Reservoir #1 Fountain.] Significance: Entertainment/Recreation is added as an area of significance. These clarifications were confirmed with the OR SHPO office DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900 ,r- OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct.1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. -

To Access the David Duniway Papers Finding Aide

Container List 1999.013 ~ Records ~ Duniway, David C. 07/19/2017 Container Folder Location Creator Date Title Description Subjects Box 01 1.01 1868-1980 Adolph-Gill Bldgs The materials in this folder relate to the buildings owned and occupied by J.K. Gill & Co. and by Sam Adolph. These two buildings are in the heart of the original business district of Salem. The Gill Building (1868) is west of the Adolph Block (1880), and they share a staircase. The Gill building was later referred to as the Paulus Building, as it was acquired by Christopher Paulus in 1885; both Robert and Fred Paulus were born upstairs in the building. The Adolph Building was erected by Sam Adolph following a fire that destroyed the wooden buildings on the site; the architect was J.S. Coulter. References to articles in the Daily American Unionist from April 23, 1868 through September 8, 1868 describe the four new brick buildings under construction on State and Commercial Streets. Thes buildings are the intended new homes for the businesses of J.K. Gill & Co., Charley Stewart, Durbin & Co., and Governor Wood's new dwelling. Progress is periodically described. Finally, the first ten days of September, 1868, the moves appear complete and advertisements indicate the items they will carry. Another article in the September 8, 1868 issue indicates that Story and Thompson are moving a house lately occupied by J.K. Gill and Co. to the eastern edge of the lot so that when it is time to construct additional brick buildings, there will be space. -

“Out of Order”

OHS Research LIbrary, OrHi 3486, photo file 930-A LIbrary, OHS Research “Out of order” Pasting Together the Slavery Debate in the Oregon Constitution AMY E. PLATT with LAURA CRAY IT MUST HAVE BEEN oppressively hot in the Marion County Courthouse on the first day of the Oregon Constitutional Convention, especially with the doors shut. The courthouse, a two-story frame building, forty feet wide and sixty-eight feet long, on the corner of Church and State Streets in Salem, was not large enough for the sixty delegates, but still they pushed in almost every day for a month, gavel to gavel, from August 17 to September 18, 1857. Many of the men were lawyers, most were farmers, and a few were miners and newspapermen.1 They brought with them their regional issues, about land and transportation and postal routes, and their strong opinions about national issues, namely slavery and religion. Perhaps most impressively, they THE FIRST MARION COUNTY COURTHOUSE was built in 1854, on the block bounded embraced the tedium of procedure, spending the first day debating bureau- by Church and High and State and Court Streets in Salem. The legislature had settled on cratic minutia and the purpose of the convention itself. Delegate Thomas Salem as the seat of government by 1857, but as the state house had burned down in 1855 Dryer, the Whig editor of the Oregonian and until 1856 a loudmouthed with no money to replace it, the courthouse was the best option for the sixty Constitutional opponent of statehood, stood up early to propose the first, but not the last, Convention delegates. -

Upstream Influence: the Economy, the State, and Oregon's Landscape, 1860-2000”

Upstream Influence: The Economy, the State, and Oregon's Landscape, 1860-2000 Devon McCurdy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: John M. Findlay, Chair Linda L. Nash Margaret Pugh O’Mara Program Authorized to Offer Degree: History © Copyright 2013 Devon McCurdy University of Washington Abstract “Upstream Influence: The Economy, the State, and Oregon's Landscape, 1860-2000” Devon McCurdy Chair of the supervisory committee: Professor John M. Findlay History This dissertation examines the ways that people in Oregon mobilized the state apparatus linked to federal, state, and city governments. It traces their efforts at state mobilization across nearly a century and a half of economic and environmental change. Two shifting ideologies shaped Oregon and its landscape between 1860 and 2000. A producerist ideology assumed a rural label and an ideology centered on place assumed an urban label. The development of these twin ideologies hardened what had been contingent boundaries between city and country. That development enshrined in Oregon politics a division between urban and rural interests. This division was never simple and rarely involved clear urban dominance over a hinterland. Portland’s relationship with the rural Northwest and the distinction between urban and rural people and landscapes that shaped it were as much the product of rural ideology as urban power. Portland was subject to upstream influence. Five episodes in Oregon and Northwest history support and explain this argument. This dissertation considers the role that global and national finance played in shaping the Northwest economy in the nineteenth century and the response that Northwest farmers made to economic elites.