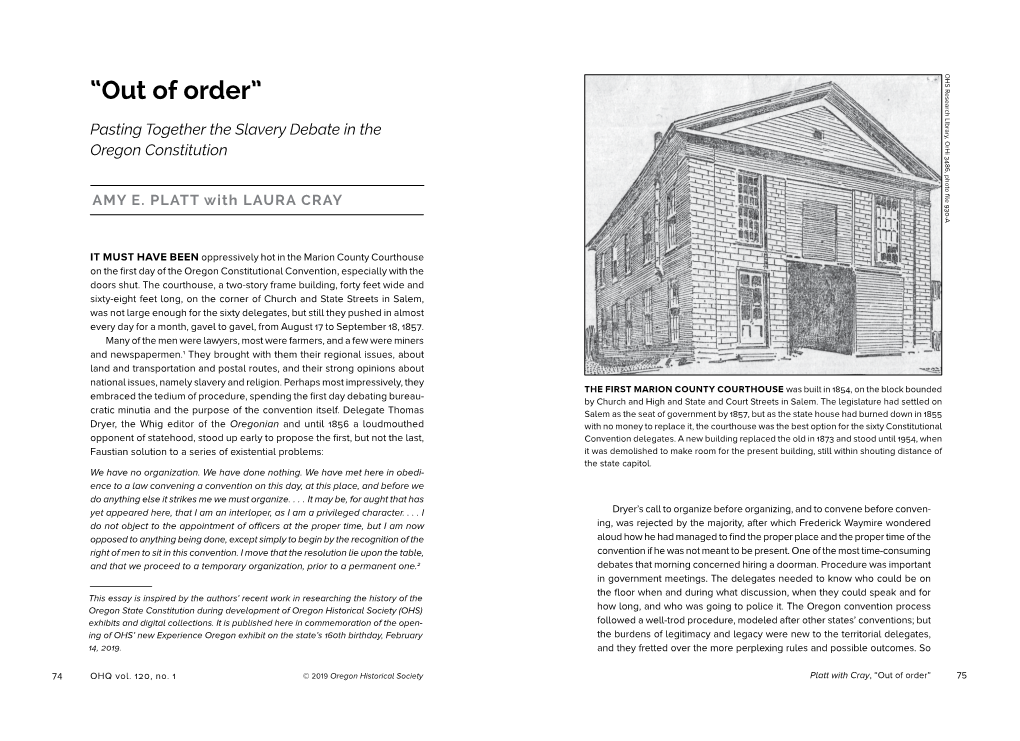

“Out of Order”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices Non-Surveyed Applegate Trail Site: East I

APPENDICES NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED Mike Walker, Member Hugo Emigrant Trails Committee (HETC) Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HNA&HS) June 5, 2015 NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED APPENDICES Appendix A. Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HuNAHS) Standards for All Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix B. HuNAHS’ Policy for Document Verification & Reliability of Evidence Appendix C. HETC’s Standards: Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix D1. Pedestrian Survey of Stockpile Site South of Chancellor Quarry in the I-5 Jumpoff Joe-Glendale Project, Josephine County (separate web page) Appendix D2. Subsurface Reconnaissance of the I-5 Chancellor Quarry Stockpile Project, and Metal Detector Survey Within the George and Mary Harris 1854 - 55 DLC (separate web page) Appendix D3. May 18, 2011 Email/Letter to James Black, Planner, Josephine County Planning Department (separate web page) Appendix D4. The Rogue Indian War and the Harris Homestead Appendix D5. Future Studies Appendix E. General Principles Governing Trail Location & Verification Appendix F. Cardinal Rules of Trail Verification Appendix G. Ranking the Reliability of Evidence Used to Verify Trial Location Appendix H. Emigrant Trail Classification Categories Appendix I. GLO Surveyors Lake & Hyde Appendix J. Preservation Training: Official OCTA Training Briefings Appendix K. Using General Land Office Notes And Maps To Relocate Trail Related Features Appendix L1. Oregon Donation Land Act Appendix L2. Donation Land Claim Act Appendix M1. Oregon Land Survey, 1851-1855 Appendix M2. How Accurate Were the GLO Surveys? Appendix M3. Summary of Objects and Data Required to Be Noted In A GLO Survey Appendix M4. -

“A Proper Attitude of Resistance”

Library of Congress, sn84026366 “A Proper Attitude of Resistance” The Oregon Letters of A.H. Francis to Frederick Douglass, 1851–1860 PRIMARY DOCUMENT by Kenneth Hawkins BETWEEN 1851 AND 1860, A.H. Francis wrote over a dozen letters to his friend Frederick Douglass, documenting systemic racism and supporting Black rights. Douglass I: “A PROPER ATTITUDE OF RESISTANCE” 1831–1851 published those letters in his newspapers, The North Star and Frederick Douglass’ Paper. The November 20, 1851, issue of Frederick Douglass’ Paper is shown here. In September 1851, when A.H. Francis flourished. The debate over whether and his brother I.B. Francis had just to extend slavery to Oregon contin- immigrated from New York to Oregon ued through the decade, eventually and set up a business on Front Street entangling A.H. in a political feud in Portland, a judge ordered them to between Portland’s Whig newspaper, in letters to Black newspapers, Francis 200 White Oregonians (who signed a leave the territory. He found them in the Oregonian, edited by Thomas explored the American Revolution’s petition to the territorial legislature on violation of Oregon’s Black exclusion Dryer, and Oregon’s Democratic party legacy of rights for Blacks, opposed their behalf), the brothers successfully law, which barred free and mixed-race organ in Salem, the Oregon States- schemes to colonize Africa with free resisted the chief Supreme Court jus- Black people from residence and man, edited by Asahel Bush.2 Francis American Black people, and extolled tice’s expulsion order and negotiated most civil rights. A.H. had been an also continued his collaboration with the opportunities available through accommodations to succeed on the active abolitionist in New York for two Douglass through a series of letters economic uplift and immigration to the far periphery of what Thomas Jefferson decades, working most recently with that Douglass published between American West. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received r3 ! I985 Inventory—Nomination Form oawemereudate entered FEB ? £« \j See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections____________________________________ 1. Name historic Markle-Pittock House and or common pjttock House 2. Location street & number 1816 SW Hawthorne Terrace for publication city, town Portland state Oregon code 41 county Multnomah code 051 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both _ X_ work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object -j^t£ in process _ X_ yes: restricted government scientific 4^, being considered _ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name and I ynne Angel street & number 1fl16 S y Havithnrne Tprrar.e city, town Portland JL/Avicinity of state QreaQn 07201 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Multnornah County Courthosue street & number m?1 SW Main city, town Portland state Qreaon 972Q4 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Historic Resource Inventory title City Of Portland, Rank II has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date 1981-1983 federal state county local depository for survey records Portland Bureau of Planning__ city, town Portland state Oregon 97204 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered _X_ original site -Xgood ruins _X_ altered moved date N/A fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Markle-Pittock House, whose construction was begun in 1888, was once considered the largest and most prominently sited residence in the city. -

Using GFO Land Records for the Oregon Territory

GENEALOGICAL MATERIALS IN FEDERAL LAND RECORDS IN THE FORUM LIBRARY Determine the Township and Range In order to locate someone in the various finding aids, books, microfilm and microfiche for land acquired from the Federal Government in Oregon, one must first determine the Township (T) and Range (R) for the specific parcel of interest. This is because the entire state was originally surveyed under the cadastral system of land measurement. The Willamette Meridian (north to south Townships) and Willamette Base Line (east to west Ranges) are the principal references for the Federal system. All land records in Oregon are organized by this system, even those later recorded for public or private transactions by other governments. Oregon Provisional Land Claims In 1843, the provisional government was organized in the Willamette Valley. In 1849 the territorial government was organized by Congress in Washington D.C. Look to see if your person of interest might have been in the Oregon Country and might have applied for an Oregon Provisional Land Claim. Use the Genealogical Material in Oregon Provisional Land Claims to find a general locality and neighbors to the person for those who might have filed at the Oregon City Land Office. This volume contains all the material found in the microfilm copy of the original records. There are over 3700 entries, with an uncounted number of multiple claims by the same person. Oregon Donation Land Claims The Donation Land Act passed by Congress in 1850 did include a provision for settlers who were residents in Oregon Territory before December 1, 1850. They were required to re-register their Provisional Land Claims in order to secure them under the Donation Land Act. -

Historical Overview

HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT The following is a brief history of Oregon City. The intent is to provide a general overview, rather than a comprehensive history. Setting Oregon City, the county seat of Clackamas County, is located southeast of Portland on the east side of the Willamette River, just below the falls. Its unique topography includes three terraces, which rise above the river, creating an elevation range from about 50 feet above sea level at the riverbank to more than 250 feet above sea level on the upper terrace. The lowest terrace, on which the earliest development occurred, is only two blocks or three streets wide, but stretches northward from the falls for several blocks. Originally, industry was located primarily at the south end of Main Street nearest the falls, which provided power. Commercial, governmental and social/fraternal entities developed along Main Street north of the industrial area. Religious and educational structures also appeared along Main Street, but tended to be grouped north of the commercial core. Residential structures filled in along Main Street, as well as along the side and cross streets. As the city grew, the commercial, governmental and social/fraternal structures expanded northward first, and with time eastward and westward to the side and cross streets. Before the turn of the century, residential neighborhoods and schools were developing on the bluff. Some commercial development also occurred on this middle terrace, but the business center of the city continued to be situated on the lower terrace. Between the 1930s and 1950s, many of the downtown churches relocated to the bluff as well. -

Trail News Fall 2018

Autumn2018 Parks and Recreation Swimming Pool Pioneer Community Center Public Library City Departments Community Information NEWS || SERVICES || INFORMATION || PROGRAMS || EVENTS City Matters—by Mayor Dan Holladay WE ARE COMMEMORATING the 175th IN OTHER EXCITING NEWS, approximately $350,000 was awarded to anniversary of the Oregon Trail. This is 14 grant applicants proposing to make improvements throughout Ore- our quarto-sept-centennial—say that five gon City utilizing the Community Enhancement Grant Program (CEGP). times fast. The CEGP receives funding from Metro, which operates the South Trans- In 1843, approximately 1,000 pioneers fer Station located in Oregon City at the corner of Highway 213 and made the 2,170-mile journey to Oregon. Washington Street. Metro, through an Intergovernmental Agreement Over the next 25 years, 400,000 people with the City of Oregon City, compensates the City by distributing a traveled west from Independence, MO $1.00 per ton surcharge for all solid waste collected at the station to be with dreams of a new life, gold and lush used for enhancement projects throughout Oregon City. These grants farmlands. As the ending point of the Ore- have certain eligibility requirements and must accomplish goals such as: gon Trail, the Oregon City community is marking this historic year ❚ Result in significant improvement in the cleanliness of the City. with celebrations and unique activities commemorating the dream- ❚ Increase reuse and recycling efforts or provide a reduction in solid ers, risk-takers and those who gambled everything for a new life. waste. ❚ Increase the attractiveness or market value of residential, commercial One such celebration was the Grand Re-Opening of the Ermatinger or industrial areas. -

Portland Blocks 178 & 212 ( 4Mb PDF )

Portland Blocks 178 & 212 Portland blocks 178 and 212 are part of the core of the city’s vibrant downtown business district and have been central to Portland’s development since the founding of the city. These blocks rest on a historical signifi cant area within the city which bridge the unique urban design district of the park blocks and the rest of downtown with its block pattern and street layout. In addition, this area includes commercial and offi ce structures along with theaters, hotels, and specialty retail outlets that testify to the economic growth of Portland’s during the twentieth century. The site of the future city of Portland, Oregon was known to traders, trappers and settlers of the 1830s and early 1840s as “The Clearing,” a small stopping place along the west bank of the Willamette River used by travellers en route between Oregon City and Fort Vancouver. In 1840, Massachusetts sea captain John Couch logged the river’s depth adjacent to The Clearing, noting that it would accommodating large ocean-going vessels, which could not ordinarily travel up-river as far as Oregon City, the largest Oregon settlement at the time. Portland’s location at the Willamette’s confl uence with the Columbia River, accessible to deep-draft vessels, gave it a key advantage over its older peer. In 1843, Tennessee pioneer William Overton and Asa Lovejoy, a lawyer from Boston, Massachusetts, fi led a land claim encompassed The Clearing and nearby waterfront and timber land. Overton sold his half of the claim to Francis W. Pettygrove of Portland, Maine. -

Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 Cessna R. Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Cessna R., "The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 258. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 by Cessna R. Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: William L. Lang, Chair David A. Horowitz David A. Johnson Barbara A. Brower Portland State University ©2011 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how the pursuit of commercial gain affected the development of agriculture in western Oregon’s Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue River Valleys. The period of study begins when the British owned Hudson’s Bay Company began to farm land in and around Fort Vancouver in 1825, and ends in 1861—during the time when agrarian settlement was beginning to expand east of the Cascade Mountains. Given that agriculture -

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

Oregon's Civil

STACEY L. SMITH Oregon’s Civil War The Troubled Legacy of Emancipation in the Pacific Northwest WHERE DOES OREGON fit into the history of the U.S. Civil War? This is the question I struggled to answer as project historian for the Oregon Historical Society’s new exhibit — 2 Years, Month: Lincoln’s Legacy. The exhibit, which opened on April 2, 2014, brings together rare documents and artifacts from the Mark Family Collection, the Shapell Manuscript Founda- tion, and the collections of the Oregon Historical Society (OHS). Starting with Lincoln’s enactment of the final Emancipation Proclamation on January , 863, and ending with the U.S. House of Representatives’ approval of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery on January 3, 86, the exhibit recreates twenty-five critical months in the lives of Abraham Lincoln and the American nation. From the moment we began crafting the exhibit in the fall of 203, OHS Museum Director Brian J. Carter and I decided to highlight two intertwined themes: Lincoln’s controversial decision to emancipate southern slaves, and the efforts of African Americans (free and enslaved) to achieve freedom, equality, and justice. As we constructed an exhibit focused on the national crisis over slavery and African Americans’ freedom struggle, we also strove to stay true to OHS’s mission to preserve and interpret Oregon’s his- tory. Our challenge was to make Lincoln’s presidency, the abolition of slavery, and African Americans’ quest for citizenship rights relevant to Oregon and, in turn, to explore Oregon’s role in these cataclysmic national processes. This was at first a perplexing task. -

Bush House Today Lies Chiefly in Its Rich, Unaltered Interior,Rn Which Includes Original Embossed French Wall Papers, Brass Fittings, and Elaborate Woodwork

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Oregon COUNTTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Mari on INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applica#ie\s&ctipns) / \ ' •• &•••» JAN 211974 COMMON: /W/' .- ' L7 w G I 17 i97«.i< ——————— Bush (Asahel) House —— U^ ——————————— AND/OR HISTORIC: \r«----. ^ „. I.... ; „,. .....,.„„.....,.,.„„,„,..,.,..,..,.,, , ,, . .....,,,.,,,M,^,,,,,,,,M,MM^;Mi,,,,^,,p'K.Qic:r,£: 'i-; |::::V^^:iX.::^:i:rtW^:^ :^^ Sii U:ljif&:ii!\::T;:*:WW:;::^^ STREET AND NUMBER: "^s / .•.-'.••-' ' '* ; , X •' V- ; '"."...,, - > 600 Mission Street s. F. W J , CITY OR TOWN: Oregon Second Congressional Dist. Salem Representative Al TJllman STATE CODE COUNT ^ : CO D E Oreeon 97301 41 Marien Q47 STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC r] District |t] Building SO Public Public Acquisit on: E Occupied Yes: r-, n . , D Restricted G Site Q Structure D Private Q ' n Process ( _| Unoccupied -j . —. _ X~l Unrestricted [ —[ Object | | Both [ | Being Consider ea Q Preservation work ^~ ' in progress ' — I PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government | | Park [~] Transportation l~l Comments | | Commercial CD Industrial | | Private Residence G Other (Specify) Q Educational d] Military Q Religious [ | Entertainment GsV Museum QJ] Scientific ...................... OWNER'S NAME: Ul (owner proponent of nomination) P ) ———————City of Salem————————————————————————————————————————— - ) -

Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Churches of Christ Heritage Center Jerry Rushford Center 1-1-1998 Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Rushford, Jerry, "Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882" (1998). Churches of Christ Heritage Center. Item 5. http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Rushford Center at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Churches of Christ Heritage Center by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIANS About the Author ON THE Jerry Rushford came to Malibu in April 1978 as the pulpit minister for the University OREGON TRAIL Church of Christ and as a professor of church history in Pepperdine’s Religion Division. In the fall of 1982, he assumed his current posi The Restoration Movement originated on tion as director of Church Relations for the American frontier in a period of religious Pepperdine University. He continues to teach half time at the University, focusing on church enthusiasm and ferment at the beginning of history and the ministry of preaching, as well the nineteenth century. The first leaders of the as required religion courses. movement deplored the numerous divisions in He received his education from Michigan the church and urged the unity of all Christian College, A.A.