North American Plate Stress Modeling: a Finite Element Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kinematic Reconstruction of the Caribbean Region Since the Early Jurassic

Earth-Science Reviews 138 (2014) 102–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic Lydian M. Boschman a,⁎, Douwe J.J. van Hinsbergen a, Trond H. Torsvik b,c,d, Wim Spakman a,b, James L. Pindell e,f a Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands b Center for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, Sem Sælands vei 24, NO-0316 Oslo, Norway c Center for Geodynamics, Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), Leiv Eirikssons vei 39, 7491 Trondheim, Norway d School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, WITS 2050 Johannesburg, South Africa e Tectonic Analysis Ltd., Chestnut House, Duncton, West Sussex, GU28 OLH, England, UK f School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3YE, UK article info abstract Article history: The Caribbean oceanic crust was formed west of the North and South American continents, probably from Late Received 4 December 2013 Jurassic through Early Cretaceous time. Its subsequent evolution has resulted from a complex tectonic history Accepted 9 August 2014 governed by the interplay of the North American, South American and (Paleo-)Pacific plates. During its entire Available online 23 August 2014 tectonic evolution, the Caribbean plate was largely surrounded by subduction and transform boundaries, and the oceanic crust has been overlain by the Caribbean Large Igneous Province (CLIP) since ~90 Ma. The consequent Keywords: absence of passive margins and measurable marine magnetic anomalies hampers a quantitative integration into GPlates Apparent Polar Wander Path the global circuit of plate motions. -

Shape of the Subducted Rivera and Cocos Plates in Southern Mexico

JOURNALOF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 100, NO. B7, PAGES 12,357-12,373, JULY 10, 1995 Shapeof the subductedRivera and Cocosplates in southern Mexico: Seismic and tectonicimplications Mario Pardo and Germdo Sufirez Insfitutode Geoffsica,Universidad Nacional Aut6noma de M6xico Abstract.The geometry of thesubducted Rivera and Cocos plates beneath the North American platein southernMexico was determined based on the accurately located hypocenters oflocal and te!eseismicearthquakes. The hypocenters ofthe teleseisms were relocated, and the focal depths of 21 eventswere constrainedusing a bodywave inversion scheme. The suductionin southern Mexicomay be approximated asa subhorizontalslabbounded atthe edges by the steep subduction geometryof theCocos plate beneath the Caribbean plate to the east and of theRivera plate beneath NorthAmerica to thewest. The dip of theinterplate contact geometry is constantto a depthof 30 kin,and lateral changes in thedip of thesubducted plate are only observed once it isdecoupled fromthe overriding plate. On thebasis of theseismicity, the focal mechanisms, and the geometry ofthe downgoing slab, southern Mexico may be segmented into four regions ß(1) theJalisco regionto thewest, where the Rivera plate subducts at a steepangle that resembles the geometry of theCocos plate beneath the Caribbean plate in CentralAmerica; (2) theMichoacan region, where thedip angleof theCocos plate decreases gradually toward the southeast, (3) theGuerrero-Oaxac.a region,bounded approximately by theonshore projection of theOrozco and O'Gorman -

Plate Tectonics Review from Valerie Nulisch Some Questions (C) 2017 by TEKS Resource System

Plate Tectonics Review from Valerie Nulisch Some questions (c) 2017 by TEKS Resource System. Some questions (c) 2017 by Region 10 Educational Service Center. Some questions (c) 2017 by Progress Testing. Page 2 GO ON A student wanted to make a model of the Earth. The student decided to cut a giant Styrofoam ball in half and paint the layers on it to show their thickness. 1 Which model below best represents the layers of the Earth? A B C D Page 3 GO ON 2 A student is building a model of the layers of the Earth. Which material would best represent the crust? F Grouping of magnetic balls G Styrofoam packing pellets H Bag of shredded paper J Thin layer of graham crackers 3 Your teacher has asked you to make a model of the interior of the Earth. In your model, how do the thicknesses of the lithosphere and crust compare? A The lithosphere is thinner than the crust. B The lithosphere is exactly the same thickness as the crust. C The lithosphere is thicker than the crust. D The lithosphere is thicker than the oceanic crust, but thinner than the continental crust. 4 Sequence the layers of the Earth in order from the exterior surface to the interior center. F Lithosphere, mantle, inner core, outer core, crust, asthenosphere G Inner core, outer core, mantle, asthenosphere, lithosphere, crust H Crust, mantle, outer core, inner core, asthenosphere, lithosphere J Crust, lithosphere, asthenosphere, mantle, outer core, inner core Page 4 GO ON 5 The tectonic plate labeled A in the diagram is the A Eurasian Plate B Indo-Australian Plate C Pacific Plate D African Plate Page 5 GO ON 6 The tectonic plate labeled B in the diagram is the — F Eurasian Plate G Indo-Australian Plate H Pacific Plate J North American Plate Page 6 GO ON Directions: The map below shows Earth's tectonic plates; six of them are numbered. -

Plate Tectonics Passport

What is plate tectonics? The Earth is made up of four layers: inner core, outer core, mantle and crust (the outermost layer where we are!). The Earth’s crust is made up of oceanic crust and continental crust. The crust and uppermost part of the mantle are broken up into pieces called plates, which slowly move around on top of the rest of the mantle. The meeting points between the plates are called plate boundaries and there are three main types: Divergent boundaries (constructive) are where plates are moving away from each other. New crust is created between the two plates. Convergent boundaries (destructive) are where plates are moving towards each other. Old crust is either dragged down into the mantle at a subduction zone or pushed upwards to form mountain ranges. Transform boundaries (conservative) are where are plates are moving past each other. Can you find an example of each type of tectonic plate boundary on the map? Divergent boundary: Convergent boundary: Transform boundary: What do you notice about the location of most of the Earth’s volcanoes? P.1 Iceland Iceland lies on the Mid Atlantic Ridge, a divergent plate boundary where the North American Plate and the Eurasian Plate are moving away from each other. As the plates pull apart, molten rock or magma rises up and erupts as lava creating new ocean crust. Volcanic activity formed the island about 16 million years ago and volcanoes continue to form, erupt and shape Iceland’s landscape today. The island is covered with more than 100 volcanoes - some are extinct, but about 30 are currently active. -

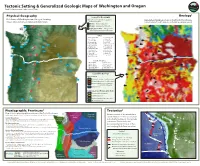

Tectonic Setting & Generalized Geologic Maps of Washington And

on the Lea rs din e g ch E a . d e . g T e Tectonic Setting & Generalized Geologic Maps of Washington and Oregon The TO TLE Pict Earthquakes ure Frank D. Granshaw and Jenda Johnson, 2009 Volcanoes Tsunamis Geology1 Physical Geography Legend for Geography Relief map of Washington and Oregon showing Map colors correspond to vegetation Generalized geologic map of the Pacific Northwest. major cities, volcanoes, lakes and waterways. and surface types: (Circled numbers are the same as on Physical Geography legend) Greens—dense vegetation 1 Browns—grasslands and desert 1 A A Light gray to white—unvegetated alpine regions in the Cascade Range 2 2 Cities A Bellingham, WA N La Grande, OR B Seattle, WA O Baker, OR B I C Tacoma, WA P Ontario, OR B I D Olympia, WA B Bend, OR E Aberdeen, WA R Klamath Falls, OR C H C F Ellensberg, WA S Medford, OR E D 3 F G Yakima, WA T Coos Bay, OR D 3 H Wenatchee, WA U Newport, OR I Spokane, WA V Astoria ,OR G J Walla Walla, WA W Portland, OR G K Pasco, WA X Salem, OR K 4 4 5 L The Dalles, OR Y Eugene, OR 5 V V M Pendleton, OR J J Cascade Volcanoes M M L L W W 1 Mount Baker 6 Mount Hood 6 6 2 Glacier Peak 7 Mount Jeerson N N 3 Mount Rainier 8 Three Sisters 4 Mount St. Helens 9 Newberry Volcano X X 5 Mount Adams 10 Crater Lake O 7 7 Legend for Geology U U Igneous Rock 8 8 Q Q Y Y P Volcanic (Less than 1.6 million years) Volcanic (More than 1.6 million years) 9 9 Volcanic (Mostly 16.5- to 6-million- year-old flood basalts) T T Intrusive rock 10 Sedimentary and Metamorphic Rock 10 Unconsolidated sediment Sedimentary rock S Sedimentary & metamorphic rock R S R Metamorphic rock Physiographic Provinces2 Tectonics3 Map of major physiographic provinces in the Pacic Northwest. -

Plate Tectonics

Plate tectonics tive motion determines the type of boundary; convergent, divergent, or transform. Earthquakes, volcanic activity, mountain-building, and oceanic trench formation occur along these plate boundaries. The lateral relative move- ment of the plates typically varies from zero to 100 mm annually.[2] Tectonic plates are composed of oceanic lithosphere and thicker continental lithosphere, each topped by its own kind of crust. Along convergent boundaries, subduction carries plates into the mantle; the material lost is roughly balanced by the formation of new (oceanic) crust along divergent margins by seafloor spreading. In this way, the total surface of the globe remains the same. This predic- The tectonic plates of the world were mapped in the second half of the 20th century. tion of plate tectonics is also referred to as the conveyor belt principle. Earlier theories (that still have some sup- porters) propose gradual shrinking (contraction) or grad- ual expansion of the globe.[3] Tectonic plates are able to move because the Earth’s lithosphere has greater strength than the underlying asthenosphere. Lateral density variations in the mantle result in convection. Plate movement is thought to be driven by a combination of the motion of the seafloor away from the spreading ridge (due to variations in topog- raphy and density of the crust, which result in differences in gravitational forces) and drag, with downward suction, at the subduction zones. Another explanation lies in the different forces generated by the rotation of the globe and the tidal forces of the Sun and Moon. The relative im- portance of each of these factors and their relationship to each other is unclear, and still the subject of much debate. -

Investigation 2: How Do We Recognize Plate Boundaries? Assessment

Investigation 2: How do we recognize plate boundaries? Assessment Answer the questions below in complete sentences. 1. What major plate lies west of the North American plate? The major plate west of the North American plate is the Pacific plate. 2. What plate lies northeast of the North American plate? The plate NE of the North American plate is the Eurasian plate. 3. What plate borders the North American plate to the southeast? The plate that borders the North American plate to the southeast is the African plate. 4. Which three plates border the North American plate to the south? The Caribbean, Cocos, and South American plates border the North American plate to the south. 5. What plate borders the North American plate in the U.S. Pacific Northwest? The plate that borders the North American plate in the U.S. Pacific Northwest is the Juan de Fuca Plate. 6. How are earthquakes and volcanoes related to plate boundaries? Earthquake clusters occur on or very near plate boundaries. Volcanoes occur about 100 kilometers away from a plate boundary in the overriding plate. 7. What kind of plate boundary separates the North American and Eurasian plates? A divergent plate boundary separates the North American and Eurasian plates. Copyright © 2012 Environmental Literacy and Inquiry Working Group at Lehigh University Investigation 2: Assessment 2 8. What kind of plate boundary separates the North American and Pacific plates at 31˚ latitude, -115˚ longitude? A transform plate boundary separates the North American and Pacific plates at 31˚ latitude, -115˚ longitude. 9. What kind of plate boundary separates the North American and Pacific plates at 55˚ latitude, -160˚ longitude? A convergent plate boundary separates the North American and Pacific plates at 55˚ latitude, -160˚ longitude. -

What Happens When Plates Collide? Assessment

Name __________________________ Investigation 6: What Happens When Plates Collide? Assessment Answer the questions below in complete sentences. Part 1: Subduction Zones 1. How deep is the trench in the Aleutian subduction zone? The trench in the Aleutian subduction zone is approximately 7,000 m below sea level. The deepest point on the elevation profile is 6,921 m below sea level. 2. a. What is the height of the volcano along the elevation profile? The highest volcano along the elevation profile is 2,517 meters in elevation (Shishaldin on Unimak Island). The actual height of the volcanoes is 2,857 meters according to the Web GIS data set. Note: When discussing this answer with students, you may point out that the elevation profile line was not drawn through the volcano’s peak. b. On which plate is this volcano located? The Shishaldin volcano is on North American Plate. 3. What is the name of the plate immediately north of the Aleutian Trench? The North American Plate is the plate located immediately north of the Aleutian Trench. 4. What is the name of the plate immediately south of the Aleutian Trench? The Pacific Plate is the plate located immediately south of the Aleutian Trench. 5. What type of plate boundary is located along the eastern section of the Aleutian Trench where most volcanoes are located? The plate boundary is convergent in the eastern section of the Aleutian Trench where most volcanoes are located. 6. What type of plate boundary is located along the western section of the Aleutian Trench where volcanoes are absent? The plate boundary is transform in the western section of the Aleutian Trench where volcanoes are absent. -

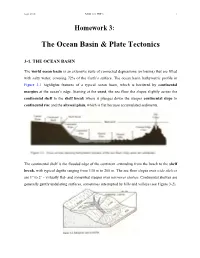

The Ocean Basin & Plate Tectonics

Sept. 2010 MAR 110 HW 3: 1 Homework 3: The Ocean Basin & Plate Tectonics 3-1. THE OCEAN BASIN The world ocean basin is an extensive suite of connected depressions (or basins) that are filled with salty water; covering 72% of the Earth’s surface. The ocean basin bathymetric profile in Figure 3-1 highlights features of a typical ocean basin, which is bordered by continental margins at the ocean’s edge. Starting at the coast, the sea floor the slopes slightly across the continental shelf to the shelf break where it plunges down the steeper continental slope to continental rise and the abyssal plain, which is flat because accumulated sediments. The continental shelf is the flooded edge of the continent -extending from the beach to the shelf break, with typical depths ranging from 130 m to 200 m. The sea floor slopes over wide shelves are 1° to 2° - virtually flat- and somewhat steeper over narrower shelves. Continental shelves are generally gently undulating surfaces, sometimes interrupted by hills and valleys (see Figure 3-2). Sept. 2010 MAR 110 HW 3: 2 The continental slope connects the continental shelf to the deep ocean, with typical depths of 2 to 3 km. While appearing steep in these vertically exaggerated pictures, the bottom slopes of a typical continental slope region are modest angles of 4° to 6°. Continental slope regions adjacent to deep ocean trenches tend to descend somewhat more steeply than normal. Sediments derived from the weathering of the continental material are delivered by rivers and continental shelf flow to the upper continental slope region just beyond the continental shelf break. -

Plate Tectonics

Plate Tectonics Introduction Continental Drift Seafloor Spreading Plate Tectonics Divergent Plate Boundaries Convergent Plate Boundaries Transform Plate Boundaries Summary This curious world we inhabit is more wonderful than convenient; more beautiful than it is useful; it is more to be admired and enjoyed than used. Henry David Thoreau Introduction • Earth's lithosphere is divided into mobile plates. • Plate tectonics describes the distribution and motion of the plates. • The theory of plate tectonics grew out of earlier hypotheses and observations collected during exploration of the rocks of the ocean floor. You will recall from a previous chapter that there are three major layers (crust, mantle, core) within the earth that are identified on the basis of their different compositions (Fig. 1). The uppermost mantle and crust can be subdivided vertically into two layers with contrasting mechanical (physical) properties. The outer layer, the lithosphere, is composed of the crust and uppermost mantle and forms a rigid outer shell down to a depth of approximately 100 km (63 miles). The underlying asthenosphere is composed of partially melted rocks in the upper mantle that acts in a plastic manner on long time scales. Figure 1. The The asthenosphere extends from about 100 to 300 km (63-189 outermost part of miles) depth. The theory of plate tectonics proposes that the Earth is divided lithosphere is divided into a series of plates that fit together like into two the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. mechanical layers, the lithosphere and Although plate tectonics is a relatively young idea in asthenosphere. comparison with unifying theories from other sciences (e.g., law of gravity, theory of evolution), some of the basic observations that represent the foundation of the theory were made many centuries ago when the first maps of the Atlantic Ocean were drawn. -

Plate Boundaries - Where the Action Is! Modeling Activity

Plate Boundaries - Where the action is! Modeling Activity The Earth’s outer shell, called the lithosphere, is broken up into tectonic plates. The lithosphere is rock that is rigid and brittle - it is composed of the crust and the uppermost mantle. The rigid plates move around on top of a hotter more mobile layer of the mantle known as the asthenosphere. Where the plates meet is where most of the world’s earthquakes and volcanic activity occurs. Let’s explore what happens at different plate boundaries. What you need: • Graham crackers • Waxed paper • Peanut butter or frosting and a knife to spread • Small bowl of water PUSH Set up: • Spread peanut butter or frosting on the waxed paper. Cover an area almost twice the size of a whole graham cracker. This is the asthenosphere – soft and mobile. • Break a graham cracker in half, now you have two tectonic plates. The PULL plates are rigid and brittle. When you broke the graham cracker... you caused an earthquake! What you’ll do: Place two graham cracker halves (tectonic plates) on your asthenosphere. Using one finger on each plate, very slowly and gently move your plates around on the asthenosphere. This is how tectonic plates on the Earth’s asthe- nosphere move. Now let’s check out the different types of boundaries between plates. Divergent Plate Boundary These are boundaries where two plates move away from each other. These boundaries are often found on ocean floors. Put the two graham cracker halves (tectonic plates) touching each other in the middle of your asthenosphere. -

Geoscenario Resources—Yellowstone Hotspot

Geoscenario Resources—Yellowstone Hotspot: Geologist Task Now that you have explored as a team, the general story of the Yellowstone Hotspot, it is time for each of you to dive into more specialized information. The geologist focuses on the historic path of the Yellowstone Hotspot and how the major geothermal features work. Add helpful details to your notes for Geoscenario Team Questions. Then work together and combine all the information to successfully present your story of the Yellowstone Hotspot. Questions for the Geologist to Consider • How do the major geothermal features in Yellowstone work? • What is the historic path of the Yellowstone Hotspot? Information Water cools near the vent’s surface. Yellowstone National Park is known for its This cooler water “caps” the hotter diverse hydrothermal features. How do they water below. Eventually, superheated work? These diagrams explain how geysers build Side channels can often release pressure water flashes to steam, expanding and within thermal systems. Side channels lifting the water above the vent in an pressure to erupt and why hot springs are so blue. can act as indicators of when primary- eruption. The brilliant colors in hot springs come from feature eruptions may occur. archaebacteria. Aptly called extremophiles for Silica is dissolved from rhyolite (the their ability to survive in extreme environments, Side Channel volcanic rock) and precipitates as these colorful organisms can live in extremely sinter, which forms the geyser cone. high temperatures. Scientists study these bacteria Sinter Sinter to understand how their cells and proteins can Sinter is deposited on the walls and acts High-pressure area caused by survive and function in environmental conditions like a throttle in the vent by constricting expanding water and steam.