Plate Boundaries - Where the Action Is! Modeling Activity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kinematic Reconstruction of the Caribbean Region Since the Early Jurassic

Earth-Science Reviews 138 (2014) 102–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic Lydian M. Boschman a,⁎, Douwe J.J. van Hinsbergen a, Trond H. Torsvik b,c,d, Wim Spakman a,b, James L. Pindell e,f a Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands b Center for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, Sem Sælands vei 24, NO-0316 Oslo, Norway c Center for Geodynamics, Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), Leiv Eirikssons vei 39, 7491 Trondheim, Norway d School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, WITS 2050 Johannesburg, South Africa e Tectonic Analysis Ltd., Chestnut House, Duncton, West Sussex, GU28 OLH, England, UK f School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3YE, UK article info abstract Article history: The Caribbean oceanic crust was formed west of the North and South American continents, probably from Late Received 4 December 2013 Jurassic through Early Cretaceous time. Its subsequent evolution has resulted from a complex tectonic history Accepted 9 August 2014 governed by the interplay of the North American, South American and (Paleo-)Pacific plates. During its entire Available online 23 August 2014 tectonic evolution, the Caribbean plate was largely surrounded by subduction and transform boundaries, and the oceanic crust has been overlain by the Caribbean Large Igneous Province (CLIP) since ~90 Ma. The consequent Keywords: absence of passive margins and measurable marine magnetic anomalies hampers a quantitative integration into GPlates Apparent Polar Wander Path the global circuit of plate motions. -

Shape of the Subducted Rivera and Cocos Plates in Southern Mexico

JOURNALOF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 100, NO. B7, PAGES 12,357-12,373, JULY 10, 1995 Shapeof the subductedRivera and Cocosplates in southern Mexico: Seismic and tectonicimplications Mario Pardo and Germdo Sufirez Insfitutode Geoffsica,Universidad Nacional Aut6noma de M6xico Abstract.The geometry of thesubducted Rivera and Cocos plates beneath the North American platein southernMexico was determined based on the accurately located hypocenters oflocal and te!eseismicearthquakes. The hypocenters ofthe teleseisms were relocated, and the focal depths of 21 eventswere constrainedusing a bodywave inversion scheme. The suductionin southern Mexicomay be approximated asa subhorizontalslabbounded atthe edges by the steep subduction geometryof theCocos plate beneath the Caribbean plate to the east and of theRivera plate beneath NorthAmerica to thewest. The dip of theinterplate contact geometry is constantto a depthof 30 kin,and lateral changes in thedip of thesubducted plate are only observed once it isdecoupled fromthe overriding plate. On thebasis of theseismicity, the focal mechanisms, and the geometry ofthe downgoing slab, southern Mexico may be segmented into four regions ß(1) theJalisco regionto thewest, where the Rivera plate subducts at a steepangle that resembles the geometry of theCocos plate beneath the Caribbean plate in CentralAmerica; (2) theMichoacan region, where thedip angleof theCocos plate decreases gradually toward the southeast, (3) theGuerrero-Oaxac.a region,bounded approximately by theonshore projection of theOrozco and O'Gorman -

Plate Tectonics Review from Valerie Nulisch Some Questions (C) 2017 by TEKS Resource System

Plate Tectonics Review from Valerie Nulisch Some questions (c) 2017 by TEKS Resource System. Some questions (c) 2017 by Region 10 Educational Service Center. Some questions (c) 2017 by Progress Testing. Page 2 GO ON A student wanted to make a model of the Earth. The student decided to cut a giant Styrofoam ball in half and paint the layers on it to show their thickness. 1 Which model below best represents the layers of the Earth? A B C D Page 3 GO ON 2 A student is building a model of the layers of the Earth. Which material would best represent the crust? F Grouping of magnetic balls G Styrofoam packing pellets H Bag of shredded paper J Thin layer of graham crackers 3 Your teacher has asked you to make a model of the interior of the Earth. In your model, how do the thicknesses of the lithosphere and crust compare? A The lithosphere is thinner than the crust. B The lithosphere is exactly the same thickness as the crust. C The lithosphere is thicker than the crust. D The lithosphere is thicker than the oceanic crust, but thinner than the continental crust. 4 Sequence the layers of the Earth in order from the exterior surface to the interior center. F Lithosphere, mantle, inner core, outer core, crust, asthenosphere G Inner core, outer core, mantle, asthenosphere, lithosphere, crust H Crust, mantle, outer core, inner core, asthenosphere, lithosphere J Crust, lithosphere, asthenosphere, mantle, outer core, inner core Page 4 GO ON 5 The tectonic plate labeled A in the diagram is the A Eurasian Plate B Indo-Australian Plate C Pacific Plate D African Plate Page 5 GO ON 6 The tectonic plate labeled B in the diagram is the — F Eurasian Plate G Indo-Australian Plate H Pacific Plate J North American Plate Page 6 GO ON Directions: The map below shows Earth's tectonic plates; six of them are numbered. -

Ocean Basin Bathymetry & Plate Tectonics

13 September 2018 MAR 110 HW- 3: - OP & PT 1 Homework #3 Ocean Basin Bathymetry & Plate Tectonics 3-1. THE OCEAN BASIN The world’s oceans cover 72% of the Earth’s surface. The bathymetry (depth distribution) of the interconnected ocean basins has been sculpted by the process known as plate tectonics. For example, the bathymetric profile (or cross-section) of the North Atlantic Ocean basin in Figure 3- 1 has many features of a typical ocean basins which is bordered by a continental margin at the ocean’s edge. Starting at the coast, there is a slight deepening of the sea floor as we cross the continental shelf. At the shelf break, the sea floor plunges more steeply down the continental slope; which transitions into the less steep continental rise; which itself transitions into the relatively flat abyssal plain. The continental shelf is the seaward edge of the continent - extending from the beach to the shelf break, with typical depths ranging from 130 m to 200 m. The seafloor of the continental shelf is gently sloping with undulating surfaces - sometimes interrupted by hills and valleys (see Figure 3- 2). Sediments - derived from the weathering of the continental mountain rocks - are delivered by rivers to the continental shelf and beyond. Over wide continental shelves, the sea floor slopes are 1° to 2°, which is virtually flat. Over narrower continental shelves, the sea floor slopes are somewhat steeper. The continental slope connects the continental shelf to the deep ocean with typical depths of 2 to 3 km. While the bottom slope of a typical continental slope region appears steep in the 13 September 2018 MAR 110 HW- 3: - OP & PT 2 vertically-exaggerated valleys pictured (see Figure 3-2), they are typically quite gentle with modest angles of only 4° to 6°. -

INTERIOR of the EARTH / an El/EMEI^TARY Xdescrrpntion

N \ N I 1i/ / ' /' \ \ 1/ / / s v N N I ' / ' f , / X GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 / N X \ i INTERIOR OF THE EARTH / AN El/EMEI^TARY xDESCRrPNTION The Interior of the Earth An Elementary Description By Eugene C. Robertson GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 532 Washington 1966 United States Department of the Interior CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary Geological Survey H. William Menard, Director First printing 1966 Second printing 1967 Third printing 1969 Fourth printing 1970 Fifth printing 1972 Sixth printing 1976 Seventh printing 1980 Free on application to Branch of Distribution, U.S. Geological Survey 1200 South Eads Street, Arlington, VA 22202 CONTENTS Page Abstract ......................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................... 1 Surface observations .............................................. 1 Openings underground in various rocks .......................... 2 Diamond pipes and salt domes .................................. 3 The crust ............................................... f ........ 4 Earthquakes and the earth's crust ............................... 4 Oceanic and continental crust .................................. 5 The mantle ...................................................... 7 The core ......................................................... 8 Earth and moon .................................................. 9 Questions and answers ............................................. 9 Suggested reading ................................................ 10 ILLUSTRATIONS -

Asthenosphere–Lithospheric Mantle Interaction in an Extensional Regime

Chemical Geology 233 (2006) 309–327 www.elsevier.com/locate/chemgeo Asthenosphere–lithospheric mantle interaction in an extensional regime: Implication from the geochemistry of Cenozoic basalts from Taihang Mountains, North China Craton ⁎ Yan-Jie Tang , Hong-Fu Zhang, Ji-Feng Ying State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O. Box 9825, Beijing 100029, PR China Received 25 July 2005; received in revised form 27 March 2006; accepted 30 March 2006 Abstract Compositions of Cenozoic basalts from the Fansi (26.3–24.3 Ma), Xiyang–Pingding (7.9–7.3 Ma) and Zuoquan (∼5.6 Ma) volcanic fields in the Taihang Mountains provide insight into the nature of their mantle sources and evidence for asthenosphere– lithospheric mantle interaction beneath the North China Craton. These basalts are mainly alkaline (SiO2 =44–50 wt.%, Na2O+ K2O=3.9–6.0 wt.%) and have OIB-like characteristics, as shown in trace element distribution patterns, incompatible elemental (Ba/Nb=6–22, La/Nb=0.5–1.0, Ce/Pb=15–30, Nb/U=29–50) and isotopic ratios (87Sr/86Sr=0.7038–0.7054, 143Nd/ 144 Nd=0.5124–0.5129). Based on TiO2 contents, the Fansi lavas can be classified into two groups: high-Ti and low-Ti. The Fansi high-Ti and Xiyang–Pingding basalts were dominantly derived from an asthenospheric source, while the Zuoquan and Fansi low-Ti basalts show isotopic imprints (higher 87Sr/86Sr and lower 143Nd/144Nd ratios) compatible with some contributions of sub- continental lithospheric mantle. The variation in geochemical compositions of these basalts resulted from the low degree partial melting of asthenosphere and the interaction of asthenosphere-derived magma with old heterogeneous lithospheric mantle in an extensional regime, possibly related to the far effect of the India–Eurasia collision. -

Tectonics and Crustal Evolution

Tectonics and crustal evolution Chris J. Hawkesworth, Department of Earth Sciences, University peaks and troughs of ages. Much of it has focused discussion on of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, the extent to which the generation and evolution of Earth’s crust is UK; and Department of Earth Sciences, University of St. Andrews, driven by deep-seated processes, such as mantle plumes, or is North Street, St. Andrews KY16 9AL, UK, c.j.hawkesworth@bristol primarily in response to plate tectonic processes that dominate at .ac.uk; Peter A. Cawood, Department of Earth Sciences, University relatively shallow levels. of St. Andrews, North Street, St. Andrews KY16 9AL, UK; and Bruno The cyclical nature of the geological record has been recog- Dhuime, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills nized since James Hutton noted in the eighteenth century that Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK even the oldest rocks are made up of “materials furnished from the ruins of former continents” (Hutton, 1785). The history of ABSTRACT the continental crust, at least since the end of the Archean, is marked by geological cycles that on different scales include those The continental crust is the archive of Earth’s history. Its rock shaped by individual mountain building events, and by the units record events that are heterogeneous in time with distinctive cyclic development and dispersal of supercontinents in response peaks and troughs of ages for igneous crystallization, metamor- to plate tectonics (Nance et al., 2014, and references therein). phism, continental margins, and mineralization. This temporal Successive cycles may have different features, reflecting in part distribution is argued largely to reflect the different preservation the cooling of the earth and the changing nature of the litho- potential of rocks generated in different tectonic settings, rather sphere. -

Plate Tectonics Passport

What is plate tectonics? The Earth is made up of four layers: inner core, outer core, mantle and crust (the outermost layer where we are!). The Earth’s crust is made up of oceanic crust and continental crust. The crust and uppermost part of the mantle are broken up into pieces called plates, which slowly move around on top of the rest of the mantle. The meeting points between the plates are called plate boundaries and there are three main types: Divergent boundaries (constructive) are where plates are moving away from each other. New crust is created between the two plates. Convergent boundaries (destructive) are where plates are moving towards each other. Old crust is either dragged down into the mantle at a subduction zone or pushed upwards to form mountain ranges. Transform boundaries (conservative) are where are plates are moving past each other. Can you find an example of each type of tectonic plate boundary on the map? Divergent boundary: Convergent boundary: Transform boundary: What do you notice about the location of most of the Earth’s volcanoes? P.1 Iceland Iceland lies on the Mid Atlantic Ridge, a divergent plate boundary where the North American Plate and the Eurasian Plate are moving away from each other. As the plates pull apart, molten rock or magma rises up and erupts as lava creating new ocean crust. Volcanic activity formed the island about 16 million years ago and volcanoes continue to form, erupt and shape Iceland’s landscape today. The island is covered with more than 100 volcanoes - some are extinct, but about 30 are currently active. -

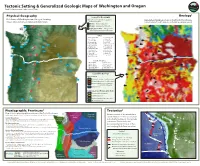

Tectonic Setting & Generalized Geologic Maps of Washington And

on the Lea rs din e g ch E a . d e . g T e Tectonic Setting & Generalized Geologic Maps of Washington and Oregon The TO TLE Pict Earthquakes ure Frank D. Granshaw and Jenda Johnson, 2009 Volcanoes Tsunamis Geology1 Physical Geography Legend for Geography Relief map of Washington and Oregon showing Map colors correspond to vegetation Generalized geologic map of the Pacific Northwest. major cities, volcanoes, lakes and waterways. and surface types: (Circled numbers are the same as on Physical Geography legend) Greens—dense vegetation 1 Browns—grasslands and desert 1 A A Light gray to white—unvegetated alpine regions in the Cascade Range 2 2 Cities A Bellingham, WA N La Grande, OR B Seattle, WA O Baker, OR B I C Tacoma, WA P Ontario, OR B I D Olympia, WA B Bend, OR E Aberdeen, WA R Klamath Falls, OR C H C F Ellensberg, WA S Medford, OR E D 3 F G Yakima, WA T Coos Bay, OR D 3 H Wenatchee, WA U Newport, OR I Spokane, WA V Astoria ,OR G J Walla Walla, WA W Portland, OR G K Pasco, WA X Salem, OR K 4 4 5 L The Dalles, OR Y Eugene, OR 5 V V M Pendleton, OR J J Cascade Volcanoes M M L L W W 1 Mount Baker 6 Mount Hood 6 6 2 Glacier Peak 7 Mount Jeerson N N 3 Mount Rainier 8 Three Sisters 4 Mount St. Helens 9 Newberry Volcano X X 5 Mount Adams 10 Crater Lake O 7 7 Legend for Geology U U Igneous Rock 8 8 Q Q Y Y P Volcanic (Less than 1.6 million years) Volcanic (More than 1.6 million years) 9 9 Volcanic (Mostly 16.5- to 6-million- year-old flood basalts) T T Intrusive rock 10 Sedimentary and Metamorphic Rock 10 Unconsolidated sediment Sedimentary rock S Sedimentary & metamorphic rock R S R Metamorphic rock Physiographic Provinces2 Tectonics3 Map of major physiographic provinces in the Pacic Northwest. -

Seismic Velocity Structure of the Continental Lithosphere from Controlled Source Data

Seismic Velocity Structure of the Continental Lithosphere from Controlled Source Data Walter D. Mooney US Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA, USA Claus Prodehl University of Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany Nina I. Pavlenkova RAS Institute of the Physics of the Earth, Moscow, Russia 1. Introduction Year Authors Areas covered J/A/B a The purpose of this chapter is to provide a summary of the seismic velocity structure of the continental lithosphere, 1971 Heacock N-America B 1973 Meissner World J i.e., the crust and uppermost mantle. We define the crust as 1973 Mueller World B the outer layer of the Earth that is separated from the under- 1975 Makris E-Africa, Iceland A lying mantle by the Mohorovi6i6 discontinuity (Moho). We 1977 Bamford and Prodehl Europe, N-America J adopted the usual convention of defining the seismic Moho 1977 Heacock Europe, N-America B as the level in the Earth where the seismic compressional- 1977 Mueller Europe, N-America A 1977 Prodehl Europe, N-America A wave (P-wave) velocity increases rapidly or gradually to 1978 Mueller World A a value greater than or equal to 7.6 km sec -1 (Steinhart, 1967), 1980 Zverev and Kosminskaya Europe, Asia B defined in the data by the so-called "Pn" phase (P-normal). 1982 Soller et al. World J Here we use the term uppermost mantle to refer to the 50- 1984 Prodehl World A 200+ km thick lithospheric mantle that forms the root of the 1986 Meissner Continents B 1987 Orcutt Oceans J continents and that is attached to the crust (i.e., moves with the 1989 Mooney and Braile N-America A continental plates). -

Physiography of the Seafloor Hypsometric Curve for Earth’S Solid Surface

OCN 201 Physiography of the Seafloor Hypsometric Curve for Earth’s solid surface Note histogram Hypsometric curve of Earth shows two modes. Hypsometric curve of Venus shows only one! Why? Ocean Depth vs. Height of the Land Why do we have dry land? • Solid surface of Earth is Hypsometric curve dominated by two levels: – Land with a mean elevation of +840 m = 0.5 mi. (29% of Earth surface area). – Ocean floor with mean depth of -3800 m = 2.4 mi. (71% of Earth surface area). If Earth were smooth, depth of oceans would be 2450 m = 1.5 mi. over the entire globe! Origin of Continents and Oceans • Crust is formed by differentiation from mantle. • A small fraction of mantle melts. • Melt has a different composition from mantle. • Melt rises to form crust, of two types: 1) Oceanic 2) Continental Two Types of Crust on Earth • Oceanic Crust – About 6 km thick – Density is 2.9 g/cm3 – Bulk composition: basalt (Hawaiian islands are made of basalt.) • Continental Crust – About 35 km thick – Density is 2.7 g/cm3 – Bulk composition: andesite Concept of Isostasy: I If I drop a several blocks of wood into a bucket of water, which block will float higher? A. A thick block made of dense wood (koa or oak) B. A thin block made of light wood (balsa or pine) C. A thick block made of light wood (balsa or pine) D. A thin block made of dense wood (koa or oak) Concept of Isostasy: II • Derived from Greek: – Iso equal – Stasia standing • Density and thickness of a body determine how high it will float (and how deep it will sink). -

Planet Earth in Cross Section by Michael Osborn Fayetteville-Manlius HS

Planet Earth in Cross Section By Michael Osborn Fayetteville-Manlius HS Objectives Devise a model of the layers of the Earth to scale. Background Planet Earth is organized into layers of varying thickness. This solid, rocky planet becomes denser as one travels into its interior. Gravity has caused the planet to differentiate, meaning that denser material have been pulled towards Earth’s center. Relatively less dense material migrates to the surface. What follows is a brief description1 of each layer beginning at the center of the Earth and working out towards the atmosphere. Inner Core – The solid innermost sphere of the Earth, about 1271 kilometers in radius. Examination of meteorites has led geologists to infer that the inner core is composed of iron and nickel. Outer Core - A layer surrounding the inner core that is about 2270 kilometers thick and which has the properties of a liquid. Mantle – A solid, 2885-kilometer thick layer of ultra-mafic rock located below the crust. This is the thickest layer of the earth. Asthenosphere – A partially melted layer of ultra-mafic rock in the mantle situated below the lithosphere. Tectonic plates slide along this layer. Lithosphere – The solid outer portion of the Earth that is capable of movement. The lithosphere is a rock layer composed of the crust (felsic continental crust and mafic ocean crust) and the portion of the mafic upper mantle situated above the asthenosphere. Hydrosphere – Refers to the water portion at or near Earth’s surface. The hydrosphere is primarily composed of oceans, but also includes, lakes, streams and groundwater.