Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

Download Download

November 27, 2008 Vol. 44 No. 33 The University of Western Ontario’s newspaper of record www.westernnews.ca PM 41195534 MARATHON MAN CANADIAN LANDSCAPE VANIER CUP Brian Groot ran five marathons in six Explore a landmark ‘word- The football Mustangs have weeks this fall in part to see if he could painting’ that captures the feel a lot to look forward to after surprise himself. That, and raise money of November in Canada. coming within one game of the for diabetes research. national title. Page 8 Page 6 Page 9 ‘Why isn’t Photoshopping for change recycling working?’ Trash audits are uncovering large volumes of recyclables B Y HEAT H ER TRAVIS he lifecycle of a plastic bottle or fine paper should Tcarry it to a blue recycling bin, however at the University of Western Ontario many of these items are getting tossed in the trash. To keep up with the problem, the Physical Plant department is playing the role of recycling watchdog. A challenge has been issued for students, faculty and staff to think twice before discarding waste – especially if it can be reused or recycled. Since Septem- ber, Physical Plant has conducted two waste audits of non-residence buildings on campus. In October, about 21 per cent of the sampled garbage was recy- clable and about 19 per cent in September. In these surveys of 10 Submitted photo buildings, Middlesex College and What would it take to get young people to vote? On the heels of a poor youth turnout for last month’s federal election, computer science students the Medical Science building had were asked to combine technology and creativity to create a marketing campaign to promote voting. -

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism by Matthew Purvis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Matthew Purvis i Abstract This dissertation concerns the relation between eroticism and nationalism in the work of a set of English Canadian artists in the mid-1960s-70s, namely John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, and Joyce Wieland. It contends that within their bodies of work there are ways of imagining nationalism and eroticism that are often formally or conceptually interrelated, either by strategy or figuration, and at times indistinguishable. This was evident in the content of their work, in the models that they established for interpreting it and present in more and less overt forms in some of the ways of imagining an English Canadian nationalism that surrounded them. The dissertation contextualizes the three artists in the terms of erotic art prevalent in the twentieth century and makes a case for them as part of a uniquely Canadian mode of decadence. Constructing my case largely from the published and unpublished writing of the three subjects and how these played against their reception, I have attempted to elaborate their artistic models and processes, as well as their understandings of eroticism and nationalism, situating them within the discourses on English Canadian nationalism and its potentially morbid prospects. Rather than treating this as a primarily cultural or socio-political issue, it is treated as both an epistemic and formal one. -

George Committees Party Appointments P.20 Young P.28 Primer Pp

EXCLUSIVE POLITICAL COVERAGE: NEWS, FEATURES, AND ANALYSIS INSIDE HARPER’S TOOTOO HIRES HOUSE LATE-TERM GEORGE COMMITTEES PARTY APPOINTMENTS P.20 YOUNG P.28 PRIMER PP. 30-31 CENTRAL P.35 TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR, NO. 1322 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2016 $5.00 NEWS SENATE REFORM NEWS FINANCE Monsef, LeBlanc LeBlanc backs away from Morneau to reveal this expected to shed week Trudeau’s whipped vote on assisted light on deficit, vision for non- CIBC economist partisan Senate dying bill, but Grit MPs predicts $30-billion BY AbbaS RANA are ‘comfortable,’ call it a BY DEREK ABMA Senators are eagerly waiting to hear this week specific details The federal government is of the Trudeau government’s plan expected to shed more light on for a non-partisan Red Cham- Charter of Rights issue the size of its deficit on Monday, ber from Government House and one prominent economist Leader Dominic LeBlanc and Members of the has predicted it will be at least Democratic Institutions Minister Joint Committee $30-billion—about three times Maryam Monsef. on Physician- what the Liberals promised dur- The appearance of the two Assisted ing the election campaign—due to ministers at the Senate stand- Suicide, lower-than-expected tax revenue ing committee will be the first pictured at from a slow economy and the time the government has pre- a committee need for more fiscal stimulus. sented detailed plans to reform meeting on the “The $10-billion [deficit] was the Senate. Also, this is the first Hill. The Hill the figure that was out there official communication between Times photograph based on the projection that the the House of Commons and the by Jake Wright economy was growing faster Senate on Mr. -

English-Speaking Canada: Blaming Women for Violence Against Wives

PERCEPTIONS - OF WIFE-BEATING " , IN POST-WORLD WAR II ENGLISH-SPEAKING CANADA: BLAMING WOMEN FOR VIOLENCE AGAINST WIVES By DIANE BARBARA PURVEY Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1982 Masters of Arts, University of Victoria, 1990 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Educational Studies) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA December 2000 © Diane Purvey, 2000 12/19/00 11:55 FAX 604 822 4244 UBC EDST In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for. financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This dissertation is an analysis of perceptions of family violence in English- speaking Canada focusing on the fifteen years after the Second World. As Canadians collectively adapted to the postwar world, authorities urged them to create strong, united families as the foundation upon which the nation depended. An idealized vision of home and family domesticated and subordinated women, and served to entrench and consolidate the dominance of white, middle-class, heterosexual, and patriarchal values. -

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

GETTING IT RIGHT for CANADIANS: the DISABILITY TAX CREDIT Standing Committee on Human Resources Development and the Status of Pe

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA GETTING IT RIGHT FOR CANADIANS: THE DISABILITY TAX CREDIT Standing Committee on Human Resources Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities Judi Longfield, M.P. Chair Carolyn Bennett, M.P. Chair Sub-Committee on the Status of Persons with Disabilities March 2002 The Speaker of the House hereby grants permission to reproduce this document, in whole or in part for use in schools and for other purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary. Any commercial or other use or reproduction of this publication requires the express prior written authorization of the Speaker of the House of Commons. If this document contains excerpts or the full text of briefs presented to the Committee, permission to reproduce these briefs, in whole or in part, must be obtained from their authors. Also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire: http://www.parl.gc.ca Available from Public Works and Government Services Canada — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 GETTING IT RIGHT FOR CANADIANS: THE DISABILITY TAX CREDIT Standing Committee on Human Resources Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities Judi Longfield, M.P. Chair Carolyn Bennett, M.P. Chair Sub-Committee on the Status of Persons with Disabilities March 2002 STANDING COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT AND THE STATUS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES CHAIR Judi Longfield VICE-CHAIRS Diane St-Jacques Carol Skelton MEMBERS Eugène Bellemare Serge Marcil Paul Crête Joe McGuire Libby Davies Anita Neville Raymonde Folco -

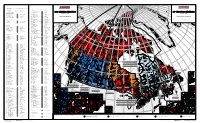

Map of Canada, Official Results of the 38Th General Election – PDF Format

2 5 3 2 a CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS Se 6 ln ln A nco co C Li in R L E ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED de ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol C A O N C t C A H Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Paul John Mark Szabo N E !( e A N L T 35051 Mississauga--Streetsville Wajid Khan A S E 38th GENERAL ELECTION R B 38 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE C I NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean--Carleton Pierre Poilievre T A I S Q Phillip TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR 35053 Newmarket--Aurora Belinda Stronach U H I s In June 28, 2004 E T L 28 juin, 2004 É 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - 10001 Avalon Hon. / L'hon. R. John Efford B E 35055 Niagara West--Glanbrook Dean Allison A N 10002 Bonavista--Exploits Scott Simms I Z Niagara-Ouest--Glanbrook E I L R N D 10003 Humber--St. Barbe--Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne a 35056 Nickel Belt Raymond Bonin E A n L N 10004 Labrador Lawrence David O'Brien s 35057 Nipissing--Timiskaming Anthony Rota e N E l n e S A o d E 10005 Random--Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews E n u F D P n d ely E n Gre 35058 Northumberland--Quinte West Paul Macklin e t a s L S i U a R h A E XEL e RÉSULTATS OFFICIELS 10006 St. -

Asper Nation Other Books by Marc Edge

Asper Nation other books by marc edge Pacific Press: The Unauthorized Story of Vancouver’s Newspaper Monopoly Red Line, Blue Line, Bottom Line: How Push Came to Shove Between the National Hockey League and Its Players ASPER NATION Canada’s Most Dangerous Media Company Marc Edge NEW STAR BOOKS VANCOUVER 2007 new star books ltd. 107 — 3477 Commercial Street | Vancouver, bc v5n 4e8 | canada 1574 Gulf Rd., #1517 | Point Roberts, wa 98281 | usa www.NewStarBooks.com | [email protected] Copyright Marc Edge 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (access Copyright). Publication of this work is made possible by the support of the Canada Council, the Government of Canada through the Department of Cana- dian Heritage Book Publishing Industry Development Program, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Printing, Cap-St-Ignace, QC First printing, October 2007 library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Edge, Marc, 1954– Asper nation : Canada’s most dangerous media company / Marc Edge. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-1-55420-032-0 1. CanWest Global Communications Corp. — History. 2. Asper, I.H., 1932–2003. I. Title. hd2810.12.c378d34 2007 384.5506'571 c2007–903983–9 For the Clarks – Lynda, Al, Laura, Spencer, and Chloe – and especially their hot tub, without which this book could never have been written. -

Puts You in Charge Inn.Y.Raid Town Man W Ith K Illing

THURSDAY, ^EPTEMBER 22, 1966 F A C E TWESTk iianclr^^ti^r Eii^nittg Ifierali:: A veitige Daily Net Press Run The Weather For the Week Xktd^ Fair and co(4 toRlglit, IMV la million dollar Interest charge September 17,1966 ■ Five,members of the Man Cub Pack 143 will have its attached to the package. 40s; mostly sunny and eon* chester 4H Homemakers Club first meeting of the year to "Recent public statements by tlnued eool tomorrow, Mgli la About Town will give demonstrations tomor morrow al 7:15 p.m. at Nathan Need Not Question the Democratic leadtfrdhlp that 14,663 mid 60bl The Women* Guild of Trini row n't the Eastern States Ex Hale'School.' All cubs and boys ‘the elected party will receive a Mancheeter—^A City of i'Ulage Charm ty Oovenent Church will meet position, Springfield, Mass. They wishing to be cubs should attend bonanza,’ following the revalu tomorrow *t 8 p.m. at the ard Miss Marjorie Peila, Miss this registration meeting ac In Vote; DellaFera ation program of Manchester's church. Gueet speaker will be (dasslfled Advert|sing on Page $01 PRICE SEVEN CENT! Janet Ackerman,^, Miss Sylvia companied by at least one par 'GOP Town Chairman Fr-ancis DellaFera said today property, and that the ‘Denao- yOL. LXXXV, NO. 301 (TWENTY-FOUR PAGESr-TWO SECTIONS) MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 1966 Mrs. John R. MoElraevy. She Peila, m Iss Carol Pelia and ent, ^ will on ‘'What Manches Miss Susan Nelkon. that the issue in the proposed $2.5 million Capital Im- “ "f * ,,'"“ '^‘2 ter is Doing for its Mentally Friendship Lodge of Masons provements Bond Issue - s »'’''her .^ o v e m e ^ Retarded Children." Hostesses will have a Grinder Sale are or are not needed. -

Core 1..40 Committee (PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25)

Standing Committee on the Status of Women FEWO Ï NUMBER 133 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 42nd PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Thursday, February 28, 2019 Chair Mrs. Karen Vecchio 1 Standing Committee on the Status of Women Thursday, February 28, 2019 probably already familiar with. According to Quebec's statistics agency, the Institut de la statistique du Québec, the province is home Ï (0850) to just over 1.5 million seniors, 54% being women and 46% being [English] men. National statistics confirm that more women than men make up The Vice-Chair (Ms. Irene Mathyssen (London—Fanshawe, the over 65 population as well as the over 85 population. NDP)): Good morning and welcome to the 133rd meeting of the Standing Committee on the Status of Women. This is a televised This demographic shift has long been known. In Quebec, 30 out meeting. of 100 people are under the age of 25 and 34 out of 100 are over 65. Today we will continue our study of the challenges faced by Despite some initial efforts, governments and agencies need to move senior women with a focus on the factors contributing to their quickly to implement comprehensive measures to support seniors as poverty and vulnerability. agents of change in society. After all, seniors have a long list of accomplishments. They still have much to say and contribute to For this meeting, we are very pleased to welcome, from society and can indeed be agents of change. l'Association québécoise de défense des droits des personnes retraitées et préretraitées, Luce Bernier, president, and Geneviève I will say that, in Canada and Quebec, the concept of gender Tremblay-Racette, director. -

54 a Shau Survivors Evacuated Over Bodies of 500

LOW TiDE 3~i2-66 i 9 AT !412 105 AT 0!30 VOL 7 KWAJAlE~N, MARSHALL ~SLANDS FR~DAY ~! MARCH 1966 WASH! NGTON (UPi )--V ~ CE PRES iDENT 54 A SHAU SURVIVORS EVACUATED HUBERT H HUMPHREY SAiD TODAY THERE OVER BODIES OF 500 COMMUNISTS "ARE NO SANCTUARIES" IN NORTH VIET NAM SAFE FROM AMER!CAN ATTACK AS SA~GOf\J /Up')--U.So i'v1ARINE HELICOPTERS FLYING 'NTO THE CO~J!rJ!UNIST DOMII~ATED JUN THERE WERE IN THE KOREAN WAR, BUT GlES f\.EAR THE LAOTIAN BORDER TODA.v RESCUED FIVE DOWtJED MARINE AIRMEfJ AND 54 VI THE VICE PRESIDEN~ [MPHASlZED THAT ETNAMESE TRIBESMEN WHO SURViVED THE MASSIVE COMMUNIST ASSAULT ON THE A SHAU SPE THE UNITED STATES Wi~l USE "ONLY CIAL FORCES CAMP A U.S. MiLITARY SPOKESMAN SAlD THE AMERiCAN AND ViETNAMESE DE SUCH POWER AS REQUiRED" UN THE ViET FENDERS O~ THE CAMP THREE MILES FROM LAOS SUFFERED "HEAV\," CA:,UAtTiES DURING TH NAM CONfliCTc HE CALkED ITSANCTUARIES" TWO-DAv ONSLAUGHT B~ 5)000 NORTH VIETNAMESE REGULARS. ~ PHRASE AND CHApTER O~ H~STORY Of HELiCOPTERS FLEW OUT 69 DEFENDERS WEDNESDAv AND YESTERDAY TODAyiS RESCUE MiS THE PREViOUS DECADE n S \ ON Wfl 5 CAR R JED 0 UT BY MA R ! NESE ARC H- AND - RES CUE HE l , COP T E RS WH i CH f LEW T 0 WA RD THE MlJZZlE~ OF T~E COMMUNIST GUNS WHICH HAD KNOCKED DOWN 1HRfE HrL JCOPTERS, A DE GAULLE SETS END OF '66 SK''(Rl\~DER II.ND A C-47 "Pu>F lH[ MAGIC FOR CLEARING OF NATO POSTS DRAGON/! GUNSH P, P T r' E Y P j C t<'E D UP F ~ vEMA.