Improve Your Chess Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

From Los Angeles to Reykjavik

FROM LOS ANGELES CHAPTER 5: TO REYKJAVIK 1963 – 68 In July 1963 Fridrik Ólafsson seized a against Reshevsky in round 10 Fridrik ticipation in a top tournament abroad, Fridrik spent most of the nice opportunity to take part in the admits that he “played some excellent which occured January 1969 in the “First Piatigorsky Cup” tournament in games in this tournament”. Dutch village Wijk aan Zee. five years from 1963 to Los Angeles, a world class event and 1968 in his home town the strongest one in the United States For his 1976 book Fridrik picked only Meanwhile from 1964 the new bian- Reykjavik, with law studies since New York 1927. The new World this one game from the Los Angeles nual Reykjavik chess international gave Champion Tigran Petrosian was a main tournament. We add a few more from valuable playing practice to both their and his family as the main attraction, and all the other seven this special event. For his birthday own chess hero and to the second best priorities. In 1964 his grandmasters had also participated at greetings to Fridrik in “Skák” 2005 Jan home players, plus provided contin- countrymen fortunately the Candidates tournament level. They Timman showed the game against Pal ued attention to chess when Fridrik Benkö from round 6. We will also have Ólafsson competed on home ground started the new biannual gathered in the exclusive Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles for a complete a look at some critical games which against some famous foreign players. international tournament double round event of 14 rounds. -

Samuel Reshevsky – Lombardy U.S

(21) Samuel Reshevsky – Lombardy U.S. Championship New York, December 1957 King’s Indian Defense [E99] By this time, in the final and deciding round for the U.S. Championship, Bobby had retained a half-point lead (over Sammy). He was paired with the black pieces against Abe Turner. He had the better of the pairing. Yet Abe was a strong master and with white could be quite dangerous. And Bobby was only thirteen. He had some psychological disadvantage against his hefty opponent. Abe was an excellent speed player and always played for stakes, but not against the child Bobby, whom in practice he had beaten many games. Word was that both were content with a draw. Bobby was unwilling to risk a loss, altogether forfeiting his grip on sharing first. And on the other hand, Abe was openly unwilling to spoil the kid’s tournament! Reshevsky had the worse pairing. I am sure that in his mind, considering he had the white pieces, he expected to win. I had lost a game to him in our match the previous year, my only loss to him so far. But I had drawn eight other games with the former prodigy. Two of these came in the 1955 Rosenwald Tournament and five others in the match. Moreover, it had only been four months since my return from the World Junior, so he certainly had to consider me with some caution. Sammy figured the Turner game would end in a draw, and so it did well before the real conflict began in his game with me. -

Livros De Xadrez

LIVROS DE XADREZ No. TÍTULO Autor Editora 1 100 Endgames You Must Know Jesus de la Villa New In Chess 2 Ajedrez - La Lucha por la Iniciativa Orestes Aldama Zambrano Paidotribo 3 Alexander Alekhine Alexander Kotov R.H.M. Press 4 Alexander Alekhine´s Best Games Alexander Alekhine Batsford Chess 5 Analysing the Endgame John Speelman Batsford Chess 6 Art of Chess Combination Znosko-Borovsky Dover 7 Attack and Defence M.Dvoretsky & A.Yusupov Batsford Chess 8 Attack and Defence in Modern Chess Tactics Ludek Pachman RPK 9 Attacking Technique Colin Crouch Batsford Chess 10 Better Chess for Average Players Tim Harding Dover 11 Bishop v/s Knight: The Veredict Steve Mayer Ice 12 Bobby Fischer My 60 Memorable Games Bobby Fischer Faber & Faber Limited 13 Bobby Fischer Rediscovered Andrew Soltis Batsford 14 Bobby Fischer: His Aproach to Chess Elie Agur Cadogan 15 Botvinnik - One Hundred Selected Games M.Botvinnik Dover 16 Building Up Your Chess Lev Alburt Circ 17 Capablanca Edward Winter McFarland 18 Chess Endgame Quis Larry Evans Cardoza Publishing 19 Chess Endings Yuri Averbach Everyman Chess 20 Chess Exam and Training Guide Igor Khmelnitsky I am Coach Press 21 Chess Middlegames Yuri Averbach Cadogan Chess 22 Chess Praxis Aron Nimzowitsch Hays Publishing 23 Chess Praxis Aron Nimzowitsch Hays Publishing 24 Chess Self-Improvement Zenon Franco Gambit 25 Chess Strategy for the Tournament Player Alburt & Palatnik Circ 26 Creative Chess Amatzia Avni Cadogan Chess 27 Creative Chess Opening Preparation Viacheslav Eingorn Gambit 28 Endgame Magic J.Beasley -

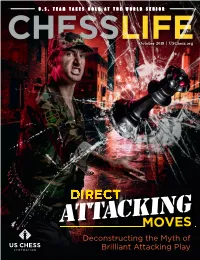

Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW!

U.S. TEAM TAKES GOLD AT THE WORLD SENIOR October 2018 | USChess.org Deconstructing the Myth of Brilliant Attacking Play NEW! GM Alexander Kalinin traces Fabiano Caruana’s career, analyses the role of his various trainers, explains the development of his playing style and points out what you can learn from his best games. With #!"$ paperback | 208 pages | $19.95 | from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDs at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum - Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked ADULT $ SCHOLASTIC $ 1 YEAR 49 1 YEAR 25 PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP In addition to these two MEMBER BENEFITS premium categories, US Chess has many •Rated Play for the US Chess community other categories and multi-year memberships •Print and digital copies of Chess Life (or Chess Life Kids) to suit your needs. For all of your options, •Promotional discounts on chess books and equipment see new.uschess.org/join- uschess/ or call •Helping US Chess grow the game 1-800-903-8723, option 4. www.uschess.org 1 Main office: Crossville, TN (931) 787-1234 Press and Communications Inquiries: [email protected] Advertising inquiries: (931) 787-1234, ext. 123 Tournament Life Announcements (TLAs): All TLAs should be e-mailed to [email protected] or sent to P.O. Box 3967, Crossville, TN 38557-3967 Letters to the editor: Please submit to [email protected] Receiving Chess Life: To receive Chess Life as a Premium Member, join US Chess, or enter a US Chess tournament, go to uschess.org or call 1-800-903-USCF (8723) Change of address: Please send to [email protected] Other inquiries: [email protected], (931) 787-1234, fax (931) 787-1200 US CHESS US CHESS STAFF EXECUTIVE Executive Director, Carol Meyer ext. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

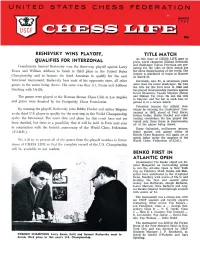

Reshevsky Wins Playoff, Qualifies for Interzonal Title Match Benko First in Atlantic Open

RESHEVSKY WINS PLAYOFF, TITLE MATCH As this issue of CHESS LIFE goes to QUALIFIES FOR INTERZONAL press, world champion Mikhail Botvinnik and challenger Tigran Petrosian are pre Grandmaster Samuel Reshevsky won the three-way playoff against Larry paring for the start of their match for Evans and William Addison to finish in third place in the United States the chess championship of the world. The contest is scheduled to begin in Moscow Championship and to become the third American to qualify for the next on March 21. Interzonal tournament. Reshevsky beat each of his opponents once, all other Botvinnik, now 51, is seventeen years games in the series being drawn. IIis score was thus 3-1, Evans and Addison older than his latest challenger. He won the title for the first time in 1948 and finishing with 1 %-2lh. has played championship matches against David Bronstein, Vassily Smyslov (three) The games wcre played at the I·lerman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles and Mikhail Tal (two). He lost the tiUe to Smyslov and Tal but in each case re and prizes were donated by the Piatigorsky Chess Foundation. gained it in a return match. Petrosian became the official chal By winning the playoff, Heshevsky joins Bobby Fischer and Arthur Bisguier lenger by winning the Candidates' Tour as the third U.S. player to qualify for the next step in the World Championship nament in 1962, ahead of Paul Keres, Ewfim Geller, Bobby Fischer and other cycle ; the InterzonaL The exact date and place for this event havc not yet leading contenders. -

Starting Out: the Sicilian JOHN EMMS

starting out: the sicilian JOHN EMMS EVERYMAN CHESS Everyman Publishers pic www.everymanbooks.com First published 2002 by Everyman Publishers pIc, formerly Cadogan Books pIc, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD Copyright © 2002 John Emms Reprinted 2002 The right of John Emms to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 857442490 Distributed in North America by The Globe Pequot Press, P.O Box 480, 246 Goose Lane, Guilford, CT 06437·0480. All other sales enquiries should be directed to Everyman Chess, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD tel: 020 7539 7600 fax: 020 7379 4060 email: [email protected] website: www.everymanbooks.com EVERYMAN CHESS SERIES (formerly Cadogan Chess) Chief Advisor: Garry Kasparov Commissioning editor: Byron Jacobs Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton Production by Book Production Services Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd., Trowbridge, Wiltshire Everyman Chess Starting Out Opening Guides: 1857442342 Starting Out: The King's Indian Joe Gallagher 1857442296 -

Yanofsky, Daniel Abraham (”Abe”) (26.03.1925 - 05.03.2000)

Yanofsky, Daniel Abraham (”Abe”) (26.03.1925 - 05.03.2000) First Canadian Grandmaster ever. Born in 1925 in Brody, then Poland, he arrived the same year in Canada, as an eight months young baby. A child prodigy. Brilliant technical play, especially in the endgame. Prominent Winnipeg lawyer and city councillor, Winnipeg, Manitoba, and Mayor of West Kildonan, Manitoba. Awarded the IM title in 1950 (the inaugural year), the GM title in 1964 and the International Arbiter title in 1977. The first chess player in the British Commonwealth to be awarded the Grandmaster title (Apart from German-born chess player Jacques Mieses who moved to England in the 1930s to escape Nazi persecution as a Jew. Mieses became a British citizen late in life, then received the title when FIDE first awarded the grandmaster title in 1950, Mieses was one of the 27 original recipients, and the oldest of them) Yanofsky was British Champion in 1953 and Canadian Champion on eight occasions: 1941 in 1943, 1945, 1947, 1953, 1959, 1963, 1965; his eight titles is a Canadian record (tied in closed tournaments with Maurice Fox). “Little Abie” or “Abe”, as the local newspapers called him soon, was a Child Prodigy. At age of 12, Yanofsky won the championship of Manitoba. He repeated every year through 1942, when nobody else even bothered to show up. Thereafter, Yanofsky was banned from further participation in the Manitoba provincial championship to encourage others to play in it :) At 14, was picked to play at board 2 for the Canadian Team in the Olympiad in Buenos Aires 1939. -

Marchapril2012.Pdf

Junior Four Nations League - a report by Mike Truran This season’s competition was bigger and better than ever, with teams of all ages competing over three weekends in two separate divisions. Like its senior equivalent, the Junior Four Nations Chess League (J4NCL) has the advantage of taking place in excellent qual- ity playing conditions in premier hotels across the UK. This season’s competition took place at Barcelo UK’s flagship Hinckley Island Hotel, so parents could also have a relaxing week- end away at a top four-star hotel while their children locked horns over the chess board. And with bedrooms and meals at the usual discounted 4NCL rates it meant that a family weekend away wasn’t going to break the bank either. 1 As well as the high quality playing conditions, the J4NCL and winning team members being presented with medals differentiates itself from most other junior events in and a trophy. So everyone got something to take home as offering free structured coaching between rounds for all a memento. the children, and the coaches also go through games on a one-to-one basis with any juniors who finish their games The standard of the chess was generally excellent, and early. This season’s coaches (GM Nick Pert, IM Andrew various parents commented on how much better many of Martin and WFM Sabrina Chevannes) did a fine job; on the juniors were playing by the third weekend compared occasion the job seemed (to this observer at least) to be as with the first. Children do of course improve fast at this much an exercise in riot control as anything else, but the age, but we like to think that the J4NCL coaching had coaches all came through in grand style and we had lots of something to do with it as well! Nonetheless, in any event compliments from parents about the quality of the coach- with a range of chess playing ability some memorable ing. -

Margate Chess Congress (1923, 1935 – 1939)

Margate Chess Congress (1923, 1935 – 1939) Margate is a seaside town and resort in the district of Thanet in Kent, England, on the coast along the North Foreland and contains the areas of Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay and Westbrook. Margate Clock Tower. Oast House Archive Margate, a photochrom print of Margate Harbour in 1897. Wikipedia The chess club at Margate, held five consecutive international tournaments from spring 1935 to spring 1939, three to five of the strongest international masters were invited to play in a round robin with the strongest british players (including Women’s reigning World Championne Vera Menchik, as well as British master players Milner-Barry and Thomas, they were invited in all five editions!), including notable "Reserve sections". Plus a strong Prequel in 1923. Record twice winner is Keres. Capablanca took part three times at Margate, but could never win! Margate tournament history Margate 1923 Kent County Chess Association Congress, Master Tournament (Prequel of the series) 1. Grünfeld, 2.-5. Michell, Alekhine, Muffang, Bogoljubov (8 players, including Réti) http://storiascacchi.altervista.org/storiascacchi/tornei/1900-49/1923margate.htm There was already a today somehow forgotten Grand Tournament at Margate in 1923, Grünfeld won unbeaten and as clear first (four of the eight invited players, namely Alekhine, Bogoljubov, Grünfeld, and Réti, were then top twelve ranked according to chessmetrics). André Muffang from France (IM in 1951) won the blitz competition there ahead of Alekhine! *********************************************************************** Reshevsky playing a simul at age of nine in the year 1920 The New York Times photo archive Margate 1st Easter Congress 1935 1. -

Qualifiers for the British Championship 2020 (Last Updated 14Th November 2019)

Qualifiers for the British Championship 2020 (last updated 14th November 2019) Section A: Qualification from the British Championship A1. British Champions Jacob Aagaard (B1), Michael Adams (A3, B1, C), Leonard Barden (B3), Robert Bellin (B3), George Botterill (B3), Stuart Conquest (B1), Joseph Gallagher (B1), William Hartston (B3), Jonathan Hawkins (A3, B1), Michael Hennigan (B3), Julian Hodgson (B1), David Howell (A3, B1), Gawain Jones (A3, B1), Raymond Keene (B1), Peter Lee, Paul Littlewood (B3), Jonathan Mestel (B1), John Nunn (B1), Jonathan Penrose (B1), James Plaskett (B1), Jonathan Rowson (B1), Matthew Sadler (B1), Nigel Short (B1), Jon Speelman (B1), Chris Ward (A3, B1), William Watson (B1), A2. British Women’s Champions Ketevan Arakhamia-Grant (B1, B2), Jana Bellin (B2), Melanie Buckley, Margaret Clarke, Joan Doulton, Amy Hoare, Jovanka Houska (A3, B2, B3), Harriet Hunt (B2, B3), Sheila Jackson (B2), Akshaya Kalaiyalahan, Susan Lalic (B2, B3), Sarah Longson, Helen Milligan, Gillian Moore, Dinah Norman, Jane Richmond (B6), Cathy Forbes (B4), A3. Top 20 players and ties in the 2018 British Championship Luke McShane (C), Nicholas Pert (B1), Daniel Gormally (B1), Daniel Fernandez (B1), Keith Arkell (A8, B1), David Eggleston (B3), Tamas Fodor (B1), Justin Hy Tan (A5), Peter K Wells (B1), Richard JD Palliser (B3), Lawrence Trent (B3), Joseph McPhillips (A5, B3), Peter T Roberson (B3), James R Adair (B3), Mark L Hebden (B1), Paul Macklin (B5), David Zakarian (B5), Koby Kalavannan (A6), Craig Pritchett (B5) A4. Top 10 players and ties in the 2018 Major Open Thomas Villiers, Viktor Stoyanov, Andrew P Smith, Jonah B Willow, Ben Ogunshola, John G Cooper, Federico Rocco (A7), Robert Stanley, Callum D Brewer, Jacob D Yoon, Jagdish Modi Shyam, Aron Teh Eu Wen, Maciej Janiszewski A5.