Sticky Cultures: Memory Publics and Communal Pasts in Competitive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999/6 Layout

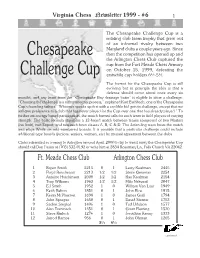

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020

World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020 World Stars 2020 ● Tournament Book ® Efstratios Grivas 2020 1 Welcome Letter Sharjah Cultural & Chess Club President Sheikh Saud bin Abdulaziz Al Mualla Dear Participants of the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020, On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Sharjah Cultural & Chess Club and the Organising Committee, I am delighted to welcome all our distinguished participants of the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020! Unfortunately, due to the recent negative and unpleasant reality of the Corona-Virus, we had to cancel our annual live events in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. But we still decided to organise some other events online, like the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020, in cooperation with the prestigious chess platform Internet Chess Club. The Sharjah Cultural & Chess Club was founded on June 1981 with the object of spreading and development of chess as mental and cultural sport across the Sharjah Emirate and in the United Arab Emirates territory in general. As on 2020 we are celebrating the 39th anniversary of our Club I can promise some extra-ordinary events in close cooperation with FIDE, the Asian Chess Federation and the Arab Chess Federation for the coming year 2021, which will mark our 40th anniversary! For the time being we welcome you in our online event and promise that we will do our best to ensure that the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship -

PAUL MORPHY Drawn

PRICE FIVE CENTS: : VOLUME 301. CEDAB EAPIDS,JOWA, SATURDAY, DECEMBER 29, 1900-12 PAGES-PAGES 9 TO 12. 1 -creditors can force their debtor' into. •3 SSI, and admittedly the .-best player to Paris and remained about eighteen ver chessmen was taken by Walter Denegre, acting for . tho Manhattan, •the court andi have an equal'settle- 'In Europe. Tn'-addition to the match months. , ' ~~- 1 ment for their accounts per ratio. games, Morphy and Anderssen played Durhig- the ten years following his Chess club of New York, price $.l.r,50: BANKRUPTCY and the silver -wreath .sold for $250, This is the involuntary act and it-;li THE LIFE OF six informal games, of which the return from Europe .in .ISM Morphy's considered by lawyers and- judges a* also bouffht by Mr. Samory. : Prussian master scored only one. The practice ot chess was limited to cas- 1 a whole just and equitable. • informal and match fiumes made a ual.games with intimate friends, chief- An engaging pastime oil chess wrlt- : sra and critics of. late years has:.been "Now comes that -portion, which B total of seventeen games played hy •ly with Charles A. -Murlan ot New COURT BUSY so generally abused, the sectlon"of that o" comparing the laf.ter-day mas- these masters, of which Morphy won Orleans and Arnons .de Riviere of which so many take advantage^-to- twelve, Anderssen throe, and two-were Paris, It Is thought,tiie total number ters with Morphy, but so far" the most flatteri-ng; comparisons have nev- ward- off the host or honest-creditors; PAUL MORPHY drawn. -

World Chess Federation (FIDE) Dear Berik Balgabajev, in 2007, the FIDE

World Chess Federation (FIDE) Dear Berik Balgabajev, In 2007, the FIDE Presidential Board gave us the right to organize the 2011 World Cup Tournament in Tallinn. We are sincerely happy to have finally received the honorable task to organize such a prestigious chess tournament. The Estonian Chess Federation has cooperated with both the state and the city government of Tallinn since 2002 trying to receive the possibility to organize a Chess Olympiad in Estonia.Taking into consideration that 2016 marks the 100th birthday of our great legendary GM Paul Keres, that year appears predestined to hold this outstanding chess event in our country. Regarding the organization of the 2011 World Cup chess tournament in Tallinn, we have been working continuously to find the best solutions and ways to guarantee a top level tournament, especially when taking the current economical situation into account. We have received requests from your side to pay the deposit of 10.000 EUR in order to emphasize our determination to organize the 2011 World Cup tournament. Before paying out the deposit, we obtained an additional confirmation from the city of Tallinn, the Estonian state and from the Estonian Olympic Committee underlining that this event has the highest priority for the whole nation, and that we still have their support for organizing the World Cup in 2011. We have received the draft of cooperation agreement previously from you and we are working on that. Since the format of the World Cup tournament has changed, as has the economical situation in the world, we are planning to send you a couple of minor suggestions, additions and appendixes to that agreement in the nearest future. -

Do First Mover Advantages Exist in Competitive Board Games: the Importance of Zugzwang

DO FIRST MOVER ADVANTAGES EXIST IN COMPETITIVE BOARD GAMES: THE IMPORTANCE OF ZUGZWANG Douglas L. Micklich Illinois State University [email protected] ABSTRACT to the other player(s) in the game (Zagal, et.al., 2006) Examples of such games are chess and Connect-Four. The players try to The ability to move first in competitive games is thought to be secure some sort of first-mover advantage in trying to attain the sole determinant on who wins the game. This study attempts some advantage of position from which a lethal attack can be to show other factors which contribute and have a non-linear mounted. The ability to move first in competitive board games effect on the game’s outcome. These factors, although shown to has thought to have resulted more often in a situation where that be not statistically significant, because of their non-linear player, the one moving first, being victorious. The person relationship have some positive correlations to helping moving first will normally try to take control from the outset and determine the winner of the game. force their opponent into making moves that they would not otherwise have made. This is a strategy which Allis refers to as “Zugzwang”, which is the principle of having to play a move INTRODUCTION one would rather not. To be able to ensure that victory through a gained advantage In Allis’s paper “A Knowledge-Based Approach of is attained, a position must first be determined. SunTzu in the Connect-Four: The Game is Solved: White Wins”, the author “Art of War” described position in this manner: “this position, a states that the player of the black pieces can follow strategic strategic position (hsing), is defined as ‘one that creates a rules by which they can at least draw the game provided that the situation where we can use ‘the individual whole to attack our player of the red pieces does not start in the middle column (the rival’s) one, and many to strike a few’ – that is, to win the (Allis, 1992). -

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels 1. Faux-gem Encrusted Cloisonné Enamel “Muslim Pattern” Chess Set Early to mid 20th century Enamel, metal, and glass Collection of the Family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky Though best known as a cellist, Jacqueline’s husband Gregor also earned attention for the beautiful collection of chess sets that he displayed at the Piatigorskys’ Los Angeles, California, home. The collection featured gorgeous sets from many of the locations where he traveled while performing as a musician. This beautiful set from the Piatigorskys’ collection features cloisonné decoration. Cloisonné is a technique of decorating metalwork in which metal bands are shaped into compartments which are then filled with enamel, and decorated with gems or glass. These green and red pieces are adorned with geometric and floral motifs. 2. Robert Cantwell “In Chess Piatigorsky Is Tops.” Sports Illustrated 25, No. 10 September 5, 1966 Magazine Published after the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, this article celebrates the immense organizational efforts undertaken by Jacqueline Piatigorsky in supporting the competition and American chess. Robert Cantwell, the author of the piece, also details her lifelong passion for chess, which began with her learning the game from a nurse during her childhood. In the photograph accompanying the story, Jacqueline poses with the chess set collection that her husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a famous cellist, formed during his travels. 3. Introduction for Los Angeles Times 1966 Woman of the Year Award December 20, 1966 Manuscript For her efforts in organizing the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, one of the strongest chess tournaments ever held on American soil, the Los Angeles Times awarded Jacqueline Piatigorsky their “Woman of the Year” award. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

Louisiana French Creole Poet, Essayist, and Composer Donna M

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Leona Queyrouze (1861-1938): Louisiana French Creole poet, essayist, and composer Donna M. Meletio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meletio, Donna M., "Leona Queyrouze (1861-1938): Louisiana French Creole poet, essayist, and composer" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2146. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2146 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LEONA QUEYROUZE (1861-1938) LOUISIANA FRENCH CREOLE POET, ESSAYIST, AND COMPOSER A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English by Donna M. Meletio B.A., University of Texas San Antonio, 1990 M.A., University of Texas San Antonio, 1994 August, 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Donna M. Meletio All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For their support throughout this project and for their patience and love, I would like to thank my daughters, Sarah, Maegan, and Kate, who are the breath and heart of my life. I would also like to thank the strong and beautiful women and men who have walked through this life journey with me: my life-long friend Dr. -

University Press of Kansas

CultureAmerica Reinventing Richard Nixon A Cultural History of an American Obsession Daniel Frick “Senator Bob Dole argued that the last half of the twentieth century was ‘the age of Nixon’ and Daniel Frick shows us why. The Nixon limned here is a mutable public figure constantly reinterpreted by his enemies and his admirers. They all find him an irresistible figure for thinking about who we are, who we want to be, and what we’re willing to do to get there. It is a brilliant and scary read.” —David Farber, author of The Age of Great Dreams: America in the 1960s “All the cultural renderings of Nixon you might ever wish to explore are provocatively analyzed here.”—David Greenberg, author of Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image 336 pages, 45 illustrations, Cloth $34.95 Weather Matters An American Cultural History since 1900 Bernard Mergen “The definitive weather book for decades to come. From weather humor to the politics of weather disaster with Katrina, from weather lore to weather prediction, from weather watchers to weather consumers, this book offers a truly comprehensive and invaluable history of weather’s enormous social and cultural impact.”—Marita Sturken, author of Desiring the Weather and Tourists of History “Mergen may know more about the cultural history of weather than anyone around and his latest book overflows with fascinating discussions.”—Gary Alan Fine, author of Authors of the Storm: Meteorologists and the Culture of Prediction 448 pages, 22 illustrations, Cloth $34.95 University Press of Kansas Phone (785) 864-4155 • Fax (785) 864-4586 www.kansaspress.ku.edu American Angels Useful Spirits in the Material World Peter Gardella “Written in a sprightly style, with an eye to pop culture, this is the first study to describe the profoundly important role that angels play in the religious imagination. -

2016 Year in Review

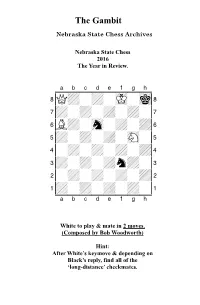

The Gambit Nebraska State Chess Archives Nebraska State Chess 2016 The Year in Review. XABCDEFGHY 8Q+-+-mK-mk( 7+-+-+-+-' 6L+-sn-+-+& 5+-+-+-sN-% 4-+-+-+-+$ 3+-+-+n+-# 2-+-+-+-+" 1+-+-+-+-! xabcdefghy White to play & mate in 2 moves. (Composed by Bob Woodworth) Hint: After White’s keymove & depending on Black’s reply, find all of the ‘long-distance’ checkmates. Gambit Editor- Kent Nelson The Gambit serves as the official publication of the Nebraska State Chess Association and is published by the Lincoln Chess Foundation. Send all games, articles, and editorial materials to: Kent Nelson 4014 “N” St Lincoln, NE 68510 [email protected] NSCA Officers President John Hartmann Treasurer Lucy Ruf Historical Archivist Bob Woodworth Secretary Gnanasekar Arputhaswamy Webmaster Kent Smotherman Regional VPs NSCA Committee Members Vice President-Lincoln- John Linscott Vice President-Omaha- Michael Gooch Vice President (Western) Letter from NSCA President John Hartmann January 2017 Hello friends! Our beloved game finds itself at something of a crossroads here in Nebraska. On the one hand, there is much to look forward to. We have a full calendar of scholastic events coming up this spring and a slew of promising juniors to steal our rating points. We have more and better adult players playing rated chess. If you’re reading this, we probably (finally) have a functional website. And after a precarious few weeks, the Spence Chess Club here in Omaha seems to have found a new home. And yet, there is also cause for concern. It’s not clear that we will be able to have tournaments at UNO in the future.