APPENDIX Table I: Literacy Rates of Selected Castes of Bombay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

![JUDGMENT [Per Ranjit More, J.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5744/judgment-per-ranjit-more-j-575744.webp)

JUDGMENT [Per Ranjit More, J.]

1 Marata(J) final.doc IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION NO. 175 OF 2018 Dr. Jishri Laxmnarao Patil, ] Member the Indian Constitutionalist ] Council, Age 39 years, Occu : Advocate, ] Having oce at C/o 109/18, ] Esplanade Mansion, M. G. Road, ] Mumbai 400023. ...Petitioner ]..Petitioner. Versus 1. The Chief Minister ] of State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ] ] 2. the Chief Secretary, ] State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ]..Respondents. WITH CIVIL APPLICATION NO. 6 OF 2019 IN PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION NO. 175 OF 2018 Gawande Sachin Sominath. ] Age 32 years, Occ : Social Activist, ] R/o Plot No. 64, Lane No. 7, Gajanan Nagar ] Garkheda Parisar, Aurangabad. ]..Applicant. IN THE MATTER BETWEEN Dr. Jishri Laxmnarao Patil, ] Member the Indian Constitutionalist ] Council, Age 39 years, Occu : Advocate, ] Having oce at C/o 109/18, ] Esplanade Mansion, M. G. Road, ] Mumbai 400023. ]..Petitioner. patil-sachin. ::: Uploaded on - 08/07/2019 ::: Downloaded on - 15/07/2019 20:18:51 ::: 2 Marata(J) final.doc Versus 1. The Chief Minister ] of State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ] ] 2. The Chief Secretary, ] State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ] ] 3. Anandrao S. Kate, ] Address at Shoop no. 12 ] Building no. 26, A, ] Lullbhai Compound, ] mumbai-400043 ] ] 4. Akhil Bhartiya Maratha ] Mahasangh, ] Reg. No. 669/A, ] Though. Dilip B Jagatap ] ts Oce at.5, Navalkar ] Lane Prarthana Samaj ] Girgaon, Mumbai-04 ] ] 5. Vilas A. Sudrik, ] 265, “Shri Ganesh Chalwal, ] Juie Aunty Compound ] Santosh Nagar, Gaorgaon (E) ] Mumbai-64 ] ] 6. Ashok Patil ] A/G/001, Mehdoot Co-op Society, ] Mahada Vasahat Thane, 4000606 ] ] 7. -

Political Economy of a Dominant Caste

Draft Political Economy of a Dominant Caste Rajeshwari Deshpande and Suhas Palshikar* This paper is an attempt to investigate the multiple crises facing the Maratha community of Maharashtra. A dominant, intermediate peasantry caste that assumed control of the state’s political apparatus in the fifties, the Marathas ordinarily resided politically within the Congress fold and thus facilitated the continued domination of the Congress party within the state. However, Maratha politics has been in flux over the past two decades or so. At the formal level, this dominant community has somehow managed to retain power in the electoral arena (Palshikar- Birmal, 2003)—though it may be about to lose it. And yet, at the more intricate levels of political competition, the long surviving, complex patterns of Maratha dominance stand challenged in several ways. One, the challenge is of loss of Maratha hegemony and consequent loss of leadership of the non-Maratha backward communities, the OBCs. The other challenge pertains to the inability of different factions of Marathas to negotiate peace and ensure their combined domination through power sharing. And the third was the internal crisis of disconnect between political elite and the Maratha community which further contribute to the loss of hegemony. Various consequences emerged from these crises. One was simply the dispersal of the Maratha elite across different parties. The other was the increased competitiveness of politics in the state and the decline of not only the Congress system, but of the Congress party in Maharashtra. The third was a growing chasm within the community between the neo-rich and the newly impoverished. -

Seeing Mumbai Through Its Hinterland Entangled Agrarian–Urban Land Markets in Regional Mumbai

Seeing Mumbai through Its Hinterland Entangled Agrarian–Urban Land Markets in Regional Mumbai Sai Balakrishnan In the past, the “money in the city, votes in the cholars often pose a puzzle of Indian cities: why do some countryside” dynamic meant that agrarian of the richest cities in the country suffer from crumbling water pipes and potholed roads? (Varshney 2011; Bjork- propertied classes wielded enough power to draw man 2015) If India’s cities generate nearly 85% of the country’s capital and resources from cities into the rural gross domestic product (GDP), why are their revenues not hinterland. However, as cities cease to be mere sites of invested in better public services? To some political scientists, extraction, agrarian elites have sought new terms the answer lies in India’s political–economic para-dox: economic power is concentrated in cities, but political power of inclusion in contemporary India’s market-oriented resides in villages (Varshney 1995). The agrarian countryside urban growth, most visibly in the endeavor of the may contribute less than 15% of the GDP, but it is also home to political class to facilitate the entry of the “sugar 80%–85% of the electorate. Politicians cannot afford to ignore constituency” into Mumbai’s real estate markets. agrarian interests without grave losses at the ballot boxes. It is this configuration of political–economic power that explains why “for politicians, the city has primarily become a site of extraction, and the countryside is predominantly a site of legitimacy and power” (Varshney 2011). The electoral power of the agrarian countryside is evident in the relationship of Mumbai to its hinterland. -

Bhakti Movement Part-3

B.A (HONS) PART-3 PAPER-5 DR.MD .NEYAZ HUSSAIN ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR & HOD PG DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MAHARAJA COLLEGE, VKSU, ARA (BIHAR) Ramanuja He was one of the earliest reformers. Born in the South, he made a pilgrimage to some of the holy places in Northern India. Considered God as an Ocean of Love and beauty. Teachings were based on the Upanishads and Bhagwad Gita. He had taught in the language of the common man. Soon a large number of people became his followers. Ramanand was his disciple He took his message to Northern parts of India. Ramananda He was the first reformer to preach in Hindi, the main language spoken by the people of the North. Educated at Benaras, lived in the 12 th Century A.D. Preached that there is nothing high or low. All men are equal in the eyes of God . He was an ardent worshipper of Rama Welcomed people of all castes and status to follow his teachings He had twelve chief disciples. One of them was a barber, another was a weaver, the third one was a cobbler and the other was the famous saint Kabir and the fifth one was a woman named Padmavathi. Considered God as a loving father. Kabir Disciple of Ramananda. It is said that he was the son of a Brahmin widow who had left him near a tank at Varanasi. A Muslim couple Niru and his wife who were weavers brought up the child . Later he became a weaver but he was attracted by the teachings of Swami Ramananda. -

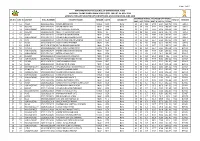

Merit Wise Selected Students List GEN-SC-ST-OBC.Xlsx

Page 1 of 10 MAHARASHTRA STATE COUNCIL OF EXAMINIATION, PUNE NATIONAL TALENT SEARCH EXAM 2018-19 (STD. 10th) DT. 04-NOV-2018 GENERAL CATEGORY SELECTED LIST FOR NATIONAL LEVEL EXAM ON 16-JUNE-2019 OBTAINED MARKS ROUNDED OFF MARKS SR.NO. DIST ID DISTRICT ROLL NUMBER STUDENT NAME GENDER CASTE DISABILITY RESULT REMARK MAT SAT TOTAL MAT % SAT % TOTAL 1 63 AKOLA E239196305162 RASIKA DINESH MAL Female GEN None 91 95 186 94.79 96.94 191.73 PASS GEN-1 2 33 JALGAON E239193303252 ARYAN RAJESH JAIN Male GEN None 89 94 183 92.71 95.92 188.63 PASS GEN-2 3 51 AURANGABAD E239195106107 AADITYA SANJAY KULKARNI Male GEN None 88 95 183 91.67 96.94 188.61 PASS GEN-3 4 33 JALGAON E239193302310 MEGH HITESHKUMAR GOHIL Male SC None 94 88 182 97.92 89.8 187.71 PASS GEN-4 5 52 JALNA E239195202402 ATHARVA RAMESH PAWAR Male GEN None 92 90 182 95.83 91.84 187.67 PASS GEN-5 6 51 AURANGABAD E239195115112 ATHARVA BALASAHEB CHIVATE Male GEN None 92 90 182 95.83 91.84 187.67 PASS GEN-6 7 21 PUNE E239192111421 SPRUHA PRABHANJAN SARNAIK Female GEN None 90 92 182 93.75 93.88 187.63 PASS GEN-7 8 52 JALNA M239195202244 YASH UDAYAN PARITKAR Male OBC None 93 89 182 96.88 89.9 186.77 PASS GEN-8 9 81 LATUR M239198102284 RUTVIK BABARUWAN MORE Male GEN None 91 91 182 94.79 91.92 186.71 PASS GEN-9 10 83 NANDED M239198302094 SAIRAJ KERBA SONMANKAR Female NT-B None 90 92 182 93.75 92.93 186.68 PASS GEN-10 11 51 AURANGABAD E239195106244 PARTH SUNILKUMAR SONGIRE Male OBC None 91 90 181 94.79 91.84 186.63 PASS GEN-11 12 51 AURANGABAD E239195110411 RITESH MOHAN PATIL Male GEN None 88 93 -

Expansion and Consolidation of Colonial Power Subject : History

Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Subject : History Lesson : Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Course Developers Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Prof. Lakshmi Subramaniam Professor, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata Dynamics of colonial expansion--1 and Dynamics of colonial expansion--2: expansion and consolidation of colonial rule in Bengal, Mysore, Western India, Sindh, Awadh and the Punjab Dr. Anirudh Deshpande Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Delhi Language Editor: Swapna Liddle Formating Editor: Ashutosh Kumar 1 Institute of lifelong learning, University of Delhi Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Table of contents Chapter 2: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power 2.2.1: Dynamics of colonial expansion - I 2.2.2: Dynamics of colonial expansion – II: expansion and consolidation of colonial rule in Bengal, Mysore, Western India, Awadh and the Punjab Summary Exercises Glossary Further readings 2 Institute of lifelong learning, University of Delhi Expansion and consolidation of colonial power 2.1: Expansion and consolidation of colonial power Introduction The second half of the 18th century saw the formal induction of the English East India Company as a power in the Indian political system. The battle of Plassey (1757) followed by that of Buxar (1764) gave the Company access to the revenues of the subas of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and a subsequent edge in the contest for paramountcy in Hindustan. Control over revenues resulted in a gradual shift in the orientation of the Company‟s agenda – from commerce to land revenue – with important consequences. This chapter will trace the development of the Company‟s rise to power in Bengal, the articulation of commercial policies in the context of Mercantilism that developed as an informing ideology in Europe and that found limited application in India by some of the Company‟s officials. -

Political Economy of Irrigation Development in Vidarbha

Political Economy Of Irrigation Development In Vidarbha SJ Phansalkar I. Introduction: • Vidarbha comprises ofthe (now) eleven Eastern districts in Maharashtra. As per the 1991 Census Over 17 million people live in some 13300 villages and nearly 100 small and big towns in Vidarbha, covering a total of 94400 sq km at a population density of 184 persons per sq km. Thirty four percent ofthese people belong to the SC/ST. While a large majority of the people speak Marathi or its dialects as their mother tongue, there is a strong influence ofHindi in all public fora. A strong sense of being discriminated against is perpetuated among the people of Vidarbha. Its origin perhaps lies in the fact that the city ofNagpur (which is the hub of all events in Vidarbha) and hence the elite living in it suffered a major diminution in importance in the country. It was the capital ofthe Central Provinces and Berar till 1956 and hence enjoyed a considerable say in public matters. The decision making hub shifted to Mumbai in 1956. Vidarbha elite have now got to compete for power with the more resourceful and crafty elite from Western Maharashtra. While largely an issue with the political elite, yet this sense of having been and still being wronged is significantly reinforced by the fact of relatively lower development of this region vis a vis other areaS in Maharashtra. For instance the CMIE Development indexes shown below indicate significantly lower level ofdevelopment for the Vidarbha area. .. Levels ofDevelopment in different districts ofVidarbha SN District Relative Index of Development as per 'CMIE 1 Akola 65 2 Amrawati 74 3 Bhandara 73 4 Buldana 59 - 5 Chandrapur 72 6 Gadchiroli 64 7 Nagpur 109 8 Wardha 99 9 Yavatmal 64 Maharashtra . -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

Bhakti Movement

TELLINGS AND TEXTS Tellings and Texts Music, Literature and Performance in North India Edited by Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield http://www.openbookpublishers.com © Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield. Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapters’ authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Orsini, Francesca and Butler Schofield, Katherine (eds.), Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0062 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#copyright All external links were active on 22/09/2015 and archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine: https://archive.org/web/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at http:// www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-102-1 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-103-8 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-104-5 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-105-2 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9978-1-78374-106-9 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0062 King’s College London has generously contributed to the publication of this volume. -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

D. S. KULKARNI DEVELOPERS LIMITED (Incorporated on September 20, 1991 Under the Companies Act, 1956) Registered & Head Office: DSK House, 1187/60, J

Offer Document Dated March 13, 2006 (Comprising Letter of Offer for The Rights Issue Component and Red Herring Prospectus for The Public Issue Component to be updated upon filing with the ROC) Please read Section 60B of the Companies Act, 1956 (Public Issue through 100% Book Built Route) D. S. KULKARNI DEVELOPERS LIMITED (Incorporated on September 20, 1991 under the Companies Act, 1956) Registered & Head Office: DSK House, 1187/60, J. M. Road, Shivajinagar, Pune - 411 005 Tel: (020) 5604 7100, Fax: (020) 2553 5772; Contact Person: Shri Ashish Boradkar (Compliance Officer) E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.dskdl.com Composite Issue of 1,10,00,000 Equity Shares of Rs. 10/- each aggregating Rs. [z] (the "Issue") comprising: 1. Rights Issue of 55,00,000 Equity Shares of Rs. 10/- each for cash at a premium of Rs. 100 per Equity Share (i.e., at a price of Rs. 110 per share) aggregating Rs. 60,50,00,000 (Rupees Sixty crores and Fifty lacs only) to the existing Equity Shareholders of the Company in the ratio of One (1) Equity Share for every Two (2) Equity Shares held as on March 21, 2006 (Record Date). 2. Public Issue of 55,00,000 Equity Shares of Rs. 10/- each for cash at a price of Rs. [z] per Equity Share aggregating Rs. [z]. The Issue comprises Promoters Contribution of 6,40,155 Equity Shares, a reservation for Employees of 1,10,000 Equity Shares of Rs. 10/- each and a net offer to the public of 47,49,845 Equity Shares of Rs.