Knotty Issues in the Pronunciation of Muskerry Irish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ireland, Western

Durgan Travel Service present s… Valid 999 DAYS/7 NIGHTS Passport Required Must be valid for 6 mos. beyond WESTERN return date IRELAND DEPARTURES: MAMAMARCHMA RCH & NOVEMBER ATATAT $$$TBATBA**** APRIL & OCTOBER ATATAT $$$TBATBA**** EARLY MAY ATATAT $$$TBA * *R ates are for payment by credit card. See back for discount cash and check rates. Rates are per person, twin occupancy, and INCLUDE $TBA in in air taxes, fees, and fuel surcharges ( subject to change ). Durgan Travel Service is pleased to offer a wonderful 9-day/7-night tour of the Emerald Isle of Ireland that will include a 3- night stay in Galway followed by 4 nights in Killarney, with a complete sightseeing package of Western Ireland and including expert tour guides, a full Irish breakfast each morning, and sumptuous dinner each evening. OUR WESTERN IRELAND TOUR ITINERARY: DAY 1 – BOSTON~IRELAND: Depart Boston’s Logan International Airport on our non-stop flight to Ireland, with full meal and beverage service, as well as stereo headsets, available while in flight. DAY 2 – SHANNON~GALWAY: Upon arrival at Shannon Airport, we will meet our Tour Escort, who will help us transfer. We will travel via Ennis and Liscannor (birthplace of John Holland, the inventor of the submarine) to the Cliffs of Moher, rising 700 feet above sea and reaching out along the coast for five miles. We will continue on via Lisdoonvarna to Galway City for a sightseeing tour. After check-in at the Victoria Hotel (or similar), we’ll have some leisure time to rest and familiarize ourselves with our surroundings. -

Download the Programme for the Xvith International Congress of Celtic Studies

Logo a chynllun y clawr Cynlluniwyd logo’r XVIeg Gyngres gan Tom Pollock, ac mae’n seiliedig ar Frigwrn Capel Garmon (tua 50CC-OC50) a ddarganfuwyd ym 1852 ger fferm Carreg Goedog, Capel Garmon, ger Llanrwst, Conwy. Ceir rhagor o wybodaeth ar wefan Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru: https://amgueddfa.cymru/oes_haearn_athrawon/gwrthrychau/brigwrn_capel_garmon/?_ga=2.228244894.201309 1070.1562827471-35887991.1562827471 Cynlluniwyd y clawr gan Meilyr Lynch ar sail delweddau o Lawysgrif Bangor 1 (Archifau a Chasgliadau Arbennig Prifysgol Bangor) a luniwyd yn y cyfnod 1425−75. Mae’r testun yn nelwedd y clawr blaen yn cynnwys rhan agoriadol Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, cyfieithiad Cymraeg o De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum, gan Hu Sant (Hugo o St. Victor). Rhan o ramadeg barddol a geir ar y clawr ôl. Logo and cover design The XVIth Congress logo was designed by Tom Pollock and is based on the Capel Garmon Firedog (c. 50BC-AD50) which was discovered in 1852 near Carreg Goedog farm, Capel Garmon, near Llanrwst, Conwy. Further information will be found on the St Fagans National Museum of History wesite: https://museum.wales/iron_age_teachers/artefacts/capel_garmon_firedog/?_ga=2.228244894.2013091070.156282 7471-35887991.1562827471 The cover design, by Meilyr Lynch, is based on images from Bangor 1 Manuscript (Bangor University Archives and Special Collections) which was copied 1425−75. The text on the front cover is the opening part of Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, a Welsh translation of De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum (Hugo of St. Victor). The back-cover text comes from the Bangor 1 bardic grammar. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Comhairle Contae Choreai Cork County Council

Halla an Cbontae, Coccaigh, Eire. Fon, (021) 4276891. Faies, (021) 4276321 Comhairle Contae Choreai Su.lomh Greasiin: www.corkcoco.ie County Hall, Cork County Council Cock, Ireland. Tel, (021) 4276891 • F=, (021) 4276321 Web: www.corkcoco.ie Administration, Environmental Licensing Programme, Office ofClimate, Licensing & Resource Use, Environmental Protection Agency, Regional Inspectorate, Inniscarra, County Cork. 30th September 20 I0 D0299-01 Re: Notice in accordance with Regulation 18(3)(b) ofthe Waste Water Discharge (Authorisation) Regulations 2007 Dear Mr Huskisson, With reference to the notice received for the Ballymakeera Waste Water Discharge Licence Application on the 2nd ofJune last and Cork County Council's response ofthe 24th June seeking a revised submission date ofthe 30th ofSeptember 2010 please find our response attached. For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. atncia Power Director of S ices, Area Operations South, Floor 5, County Hall, Cork. EPA Export 26-07-2013:23:31:10 Revised Non-Technical Summary – Sept 2010 Ballyvourney and Ballymakeera are two contiguous settlements located approximately 15 kilometres northwest of Macroom on the main N22 Cork to Killarney road and are the largest settlements located within the Muskerry Gaeltacht region. The Waste Water Works and the Activities Carried Out Therein Until the sewer upgrade in 2007 the sewer network served only the eastern part of the combined area and discharged to a septic tank which has an outfall that discharges to the River Sullane. The existing sewers had inadequate capacity and some of the older pipelines had been laid at a relatively flat fall and so could not achieve self cleansing velocities. -

What's in an Irish Name?

What’s in an Irish Name? A Study of the Personal Naming Systems of Irish and Irish English Liam Mac Mathúna (St Patrick’s College, Dublin) 1. Introduction: The Irish Patronymic System Prior to 1600 While the history of Irish personal names displays general similarities with the fortunes of the country’s place-names, it also shows significant differences, as both first and second names are closely bound up with the ego-identity of those to whom they belong.1 This paper examines how the indigenous system of Gaelic personal names was moulded to the requirements of a foreign, English-medium administration, and how the early twentieth-century cultural revival prompted the re-establish- ment of an Irish-language nomenclature. It sets out the native Irish system of surnames, which distinguishes formally between male and female (married/ un- married) and shows how this was assimilated into the very different English sys- tem, where one surname is applied to all. A distinguishing feature of nomen- clature in Ireland today is the phenomenon of dual Irish and English language naming, with most individuals accepting that there are two versions of their na- me. The uneasy relationship between these two versions, on the fault-line of lan- guage contact, as it were, is also examined. Thus, the paper demonstrates that personal names, at once the pivots of individual and group identity, are a rich source of continuing insight into the dynamics of Irish and English language contact in Ireland. Irish personal names have a long history. Many of the earliest records of Irish are preserved on standing stones incised with the strokes and dots of ogam, a 1 See the paper given at the Celtic Englishes II Colloquium on the theme of “Toponyms across Languages: The Role of Toponymy in Ireland’s Language Shifts” (Mac Mathúna 2000). -

Intonation in Déise Irish

ENGAGING WITH ROBUST CROSS-PARTICIPANT VARIABILITY IN AN ENDANGERED MINORITY VARIETY: INTONATION IN DÉISE IRISH Connor McCabe Trinity College, Dublin [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper adapts data and analyses from unpublished recent work on Déise prosody [11], This paper explores the issue of speaker uniformity in elaborating on the importance of engaging with and the phonetic study of endangered language varieties, seeking to explain participant variability. Distribution with reference to work on the dialect of Irish (Gaelic) of intonational features (described autosegmentally- spoken in Gaeltacht na nDéise (Co. Waterford). metrically using IViE; [7]) is compared with Detailed prosodic study of this subvariety of Munster participant age and relative ‘traditionalness’. A 10- Irish directly engaged with variation across point traditionalness scale based on phonological, generations and degrees of ‘traditionalness’. Age and lexical, morphosyntactic, and acquisition factors is score on a 10-point traditionalness scale showed no used, experimenting with a quantitative approach to correlation with one another, justifying the intuitions found in the literature on variation in consideration of the two as distinct factors. endangered speaker populations [5,8,10,14]. A falling H*+L predominated in both prenuclear and nuclear position. Relative distribution of pitch Figure 1. Map of Ireland with Gaeltacht areas indicated accent types (H*+L, H*, L*+H) and boundary tones in bold [16], and arrow indicating the Déise (H%, 0%) frequently correlated with participant age, and more rarely with traditionalness score. The importance of a realistic view of interspeaker variability in endangered varieties, and how to approach this quantitatively, is discussed. Keywords: Intonation, variation, sociophonetics, endangered varieties 1. -

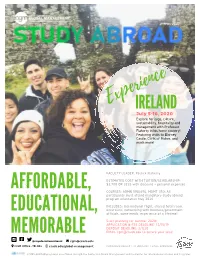

Experience of a Lifetime!

summer 2020 ce rien xpe E IR ELAND July 5-16, 2020 Explore heritage, culture, sustainability, hospitality and management with Professor Flaherty in his home country! Featuring visits to Blarney Castle, Cliffs of Moher, and much more! FACULTY LEADER: Patrick Flaherty ESTIMATED COST WITH TUITION/SCHOLARSHIP: AFFORDABLE, $3,700 OR LESS with discount + personal expenses COURSES: ADMN 590/690, MGMT 350; All participants must attend mandatory study abroad program orientation May 2020 EDUCATIONAL, INCLUDES: International flight, shared hotel room, excursions, networking with business/government officials, some meals, experience of a lifetime! Start planning for summer 2020! APPLICATION & FEE DEADLINE: 12/15/19 MEMORABLE DEPOSIT DEADLINE: 2/1/20 EMAIL [email protected] to secure your seat! @coyotesinternational [email protected] CGM Office : JB 404 csusb.edu/global-management PROGRAMS SUBJECT TO UNIVERSITY FINAL APPROVAL STUDY ABROAD programs are offered through the Center for Global Management and the Center for International Studies and Programs Email: [email protected] http://www.aramfo.org Phone: (303) 900-8004 CSUSB Ireland Travel Course July 5 to 16, 2020 Final Hotels: Hotel Location No. of nights Category Treacys Hotel Waterford 2 nights 3 star Hibernian Hotel Mallow, County Cork 2 nights 3 star Lahinch Golf Hotel County Clare 1 night 4 star Downhill Inn Hotel Ballina, County Mayo 1 night 3 star Athlone Springs Hotel Athlone 1 night 4 star Academy Plaza Hotel Dublin 3 nights 3 star Treacys Hotel, No. 1 Merchants Quay, Waterford city. Rating: 3 Star Website: www.treacyshotelwaterford.com Treacy’s Hotel is located on Waterford’s Quays, overlooking the Suir River. -

Exceptional Stress and Reduced Vowels in Munster Irish Anton Kukhto

Exceptional stress and reduced vowels in Munster Irish Anton Kukhto Massachusetts Institute of Technology [email protected] ABSTRACT 1.2. Exceptions to the basic pattern This paper focuses on reduced vowels in one of the Munster dialects of Modern Irish, Gaeilge Chorca There exist, however, numerous exceptions to this Dhuibhne. In this dialect, lexical stress depends on rule. Some are caused by the morphological structure syllable weight: heavy syllables (i.e. syllables that of the word. Thus, some verbal inflection morphemes contain phonologically long vowels) attract stress; if exceptionally attract lexical stress, e.g. fógróidh (sé) [foːgǝˈroːgj] ‘(he) will announce’, while others fail to there are none, stress is initial. There exist exceptions, j j one of them being peninitial stress in words with no do so contrary, e.g. molaimíd [ˈmoləm iːd ] ‘we heavy syllables and the string /ax/ in the second praise’; for more details on such cases, see [21]. Other syllable. Instead of deriving this pattern from the exceptions are lexical in the sense that the stress is properties of /x/ in combination with /a/ as has been unpredictable and does not obey the general laws done in much previous work, the paper argues for the outlined above. These are often found to exhibit presence of a phonologically reduced vowel in the anomalous behaviour in other Irish dialects as well, first syllable. The paper argues that such vowels are not only in the South, cf. tobac [tǝˈbak] ‘tobacco’ or phonetically and phonologically different from bricfeasta [brʲikˈfʲastǝ] ‘breakfast’. underlying full vowels that underwent a post-lexical Another class of exceptions seems to stem from process of vowel reduction. -

Examining Irish Nationalism in the Context of Literature, Culture and Religion

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Mary Immaculate Research Repository and Digital Archive EXAMINING IRISH NATIONALISM IN THE CONTEXT OF LITERATURE, CULTURE AND RELIGION A Study of the Epistemological Structure of Nationalism by Eugene O’Brien i Examining Irish Nationalism in the Context of Literature, Culture and Religion by EUGENE O’BRIEN University of Limerick Ireland Studies in Irish Literature Editor Eugene O’Brien The Edwin Mellen Press Lewiston • Queenston • Lampeter ii iii iv For Áine, Eoin, Dara and Sinéad v vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgements xi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AETIOLOGY OF NATIONALISM - DEFINITIONS 9 CHAPTER 2: NATIONALIST REFLECTIONS AND MISRECOGNITIONS 45 CHAPTER 3: MAPPING NATIONALISM – LAND AND LANGUAGE 71 CHAPTER 4: NATIONALISM AND FAITH 97 CONCLUSION 133 NOTES 139 WORKS CITED 147 BIBLIOGRAPHY 157 INDEX 165 vii viii PREFACE It seems appropriate, as the island of Ireland is about to enter a fresh and as yet unpredictable phase in its collective history, that this book should appear. Politically, the stalled Northern Ireland peace process is about to be restarted; while socially, the influx of refugees and economic migrants from Eastern Europe and the African continent is forcing us as a people to reconsider our image of ourselves as welcoming and compassionate. By isolating and interrogating the nationalist mythos, Eugene O’Brien’s book problematises the very basis of our thinking about ourselves, yet shows how that thinking is common to nations and nationalist groups throughout the world. O’Brien’s strategy in this book is an important departure in the study of Irish nationalism. -

Mac Grianna and Conrad: a Case Study in Translation

Mac Grianna and Conrad: A Case Study in Translation Sinéad Coyle Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. to the Faculty of Arts, University of Ulster, Magee Campus, Derry October 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words I Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………… IV ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………………… V ABBREVIATIONS VI ACCESS TO CONTENTS ........................................................................................ VII INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... - 1 - METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................... - 6 - CHAPTER 1 ........................................................................................................... - 7 - REVIEW OF TRANSLATION STUDIES ................................................................. - 7 - INTRODUCTION: BACKGROUND TO TRANSLATION STUDIES ....................................... - 7 - TRANSLATION BEFORE THE TWENTIETH CENTURY .................................................... - 9 - LINGUISTIC THEORIES OF TRANSLATION................................................................. - 18 - POSTMODERN THEORY AND ITS INFLUENCE ON TRANSLATION STUDIES ................... - 25 - POST-COLONIAL TRANSLATION THEORY ................................................................ - 29 - PHILOSOPHICAL APPROACHES TO TRANSLATION .................................................... - 32 - DERRIDA AND DECONSTRUCTION -

Building Register Q1 2017

Building Register Q1 2017 Notice Type Notice No. Local Authority Commencement Date Description Development Location Planning Permission Validation Date Owner Name Owner Company Owner Address Builder Name Builder Company Designer Name Designer Company Certifier Name Certifier Company Completion Cert No. Number Opt Out Commencement CN0026067CW Carlow County Council 11/04/2017 Construction of two storey dwelling, Ballinkillen, Bagenalstown, 11261 31/03/2017 Mary Kavanagh Kilcumney Anthony Keogh Keogh brothers Mary Kavanagh Notice wastewater treatment system and carlow Goresbridge construction percolation area, provision of a new Goresbridge splayed entrance, bored well and all kilkenny 0000 associated site works Opt Out Commencement CN0026063CW Carlow County Council 11/04/2017 Opt Out Erection of a two storey Ballynoe, Ardattin, carlow 1499 31/03/2017 Robert & Ciara The Cottage Robert & Ciara Robert & Ciara Notice extension to existing cottage. Stanley Ardattin Ardattin Stanley Stanley carlow Short Commencement CN0025855CW Carlow County Council 10/04/2017 To demolish single storey portion to 45 Green Road, Carlow, carlow 16/45 24/03/2017 John & Rosemarie Dean Design The Millhouse John & Rosemarie Dean Design John & Rosemarie Dean Design Notice the side of existing semi - detached Moore Dunleckney Moore Moore two storey dwelling house, full Bagenalstown planning permission is sought to Bagenalstown construct a single storey/two storey carlow Wicklow extension to the side of existing dwelling house including alterations to the front elevation to accommodate proposed extension, all ancillary site works and services Opt Out Commencement CN0025910CW Carlow County Council 10/04/2017 To construct a single storey extension Mountain View House, Green 16368 27/03/2017 Margaret McHugh Mountain View Michael Redmond Patrick Byrne Planning & Design Notice to the side of existing single storey Road, carlow House Solutions dwelling with basement and all Green Road Carlow associated site works Mountain View carlow House, Green Road, Carlow. -

Big House Burnings in County Cork During the Irish Revolution, 1920–21*

James S. Big House Burnings Donnelly, Jr. in County Cork during the Irish Revolution, 1920–21* Introduction The burning of Big Houses belonging to landed Protestants and the occasional Catholic was one of the most dramatic features of the Irish Revolution of 1919–23. Of course, the Protestant landed elite was only a shadow of its former self in the southern parts of Ireland by the time that revolution erupted in 1919. But even where land- owners had sold their estates to their tenants, they usually retained considerable demesnes that they farmed commercially, and they still held a variety of appointments under the British crown—as lieuten- ants or deputy lieutenants of counties and as justices of the peace. Symbols of an old regime in landownership that was not yet dead, and loyal to the British crown and empire, members of the tradi- tional elite were objects of suspicion and sometimes outright hostil- ity among IRA members and nationalists more generally. For many Southern Unionists or loyalists with Big Houses and some land, life became extremely uncomfortable and often dangerous after 1919. Nowhere was this truer than in County Cork. In his important study The Decline of the Big House in Ireland, Terence Dooley put *I wish to express my gratitude to careful readers of this article in earlier drafts, including Fergus Campbell, L. Perry Curtis, Jr., Ian d’Alton, Tom Dunne, and Cal Hyland. While saving me from errors, they also made valuable suggestions. I must thank Leigh-Ann Coffey for generously allowing me to draw upon her digitized col- lection of documents from the Colonial Office records pertaining to the Irish Grants Committee at the U.K.