Chapter Six Emergence and Growth of Nationalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTION COMMISSION 18, SAROJINI NAIDU SARANI (Rawdon Street) KOLKATA – 700 017 Ph No.2280-5277 ; FAX: 2

WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTION COMMISSION 18, SAROJINI NAIDU SARANI (Rawdon Street) – KOLKATA 700 017 Ph No.2280-5277 ; FAX: 2280-7373 No. 1809-SEC/1D-131/2012 Kolkata, the 3rd December 2012 In exercise of the power conferred by Sections 16 and 17 of the West Bengal Panchayat Elections Act, 2003 (West Bengal Act XXI of 2003), read with rules 26 and 27 of the West Bengal Panchayat Elections Rules, 2006, West Bengal State Election Commission, hereby publish the draft Order for delimitation of Malda Zilla Parishad constituencies and reservation of seats thereto. The Block(s) have been specified in column (1) of the Schedule below (hereinafter referred to as the said Schedule), the number of members to be elected to the Zilla Parishad specified in the corresponding entries in column (2), to divide the area of the Block into constituencies specified in the corresponding entries in column (3),to determine the constituency or constituencies reserved for the Scheduled Tribes (ST), Scheduled Castes (SC) or the Backward Classes (BC) specified in the corresponding entries in column (4) and the constituency or constituencies reserved for women specified in the corresponding entries in column (5) of the said schedule. The draft will be taken up for consideration by the State Election Commissioner after fifteen days from this day and any objection or suggestion with respect thereto, which may be received by the Commission within the said period, shall be duly considered. THE SCHEDULE Malda Zilla Parishad Malda District Name of Block Number of Number, Name and area of the Constituen Constituen members to be Constituency cies cies elected to the reserved reserved Zilla Parishad for for ST/SC/BC Women persons (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) Bamongola 2 Bamongola/ZP-1 SC Women Madnabati, Gobindapur- Maheshpur and Bamongola grams Bamongola/ZP-2 SC Chandpur, Pakuahat and Jagdala grams HaHbaibipbupru/rZ P- 3 Women 3 Habibpur/ZP-4 ST Women Mangalpura , Jajoil, Kanturka, Dhumpur and Aktail and Habibpur grams. -

West Bengal Bikash Bidhan Nagar, Calc Antiual Report 1999-2000

r Department of School Education A Government of West Bengal Bikash Bidhan Nagar, Calc Antiual Report 1999-2000 Department of School Education Government of West Bengal Bikash Bhavan Bidhan Nagar, Calcutta-700 091 \amtuu of B4u«tcioQ«t PiittQiai «a4 A4niMttriti«o. ll^ ii Sri A«ir»kBdo M«rg, ! X a n i i C S i s w a s Minister-in-charge DEPT. OF EDUCATION (PRIMARY, SECONDARY AND MADRASAH) & DEPT. OF REFUGEE RELIEF AND REHABILITATION Government of West Bengal Dated, Calcutta 28.6.2000 FOREWORD It is a matter of satisfaction to me that 4th Annual Report of the Department of School Education, Government of West Bengal is being presented to all concerned who are interested to know the facts and figures of the system and achievements of the Department. The deficiencies which were revealed in the last 3 successive reports have been tried to be overcome in this report. The figures in relation to all sectors of School Education Department have been updated. All sorts of efforts have been taken in preparation of this Annual Report sO that the report may be all embracing in respect of various information of this Department. All the facts and figures in respect of achievement of Primary Education including the District Primary Education Programme have been incorporated in this Report. The position of Secondary School have been clearly adumbrated in this issue. At the same time, a large number of X-class High Schools which have been upgraded to Higher Secondary Schools (XI-XII) have also been mentioned in this Report. -

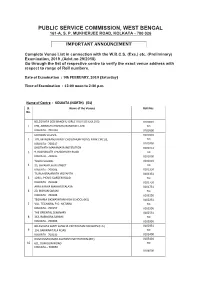

Complete Names and Addresses of the Venues of the Upcoming West

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. P. MUKHERJEE ROAD, KOLKATA - 700 026 IMPORTANT ANNOUNCEMENT Complete Venue List in connection with the W.B.C.S. (Exe.) etc. (Preliminary) Examination, 2019 ,(Advt.no 29/2018) Go through the list of respective centre to verify the exact venue address with respect to range of Roll numbers. Date of Examination : 9th FEBRUARY, 2019 (Saturday) Time of Examination : 12:00 noon to 2:30 p.m. Name of Centre : KOLKATA (NORTH) (01) Sl. Name of the Venues Roll Nos. No. BELEGHATA DESHBANDHU GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL (HS) 0100001 1 69B, ABINASH CHANDRA BANERJEE LANE TO KOLKATA - 700 010 0100500 MODERN SCHOOL 0100501 2 17B, MANORANJAN ROY CHOUDHURY ROAD, PARK CIRCUS, TO KOLKATA - 700017 0100750 BHUTNATH MAHAMAYA INSTITUTION 0100751 3 9, RADHANATH CHOWDHURY ROAD TO KOLKATA - 700015 0101000 TOWN SCHOOL 0101001 4 33, SHYAMPUKUR STREET TO KOLKATA - 700004 0101350 TILJALA BRAJANATH VIDYAPITH 0101351 5 129/1, PICNIC GARDEN ROAD TO KOLKATA - 700039 0101750 ARYA KANYA MAHAVIDYALAYA 0101751 6 20, BIDHAN SARANI TO KOLKATA - 700006 0102250 TEGHARIA SIKSHAYATAN HIGH SCHOOL (HS) 0102251 7 VILL. TEGHARIA, P.O. HATIARA TO KOLKATA - 700157 0102550 THE ORIENTAL SEMINARY 0102551 8 363, RABINDRA SARANI TO KOLKATA - 700006 0102950 BELEGHATA SANTI SANGHA VIDYAYATAN FOR BOYS (H.S.) 0102951 9 1/4, BARWARITALA ROAD TO KOLKATA - 700010 0103400 DUM DUM KUMAR ASUTOSH INSTITUTIOIN (BR.) 0103401 10 6/1, DUM DUM ROAD TO KOLKATA – 700030 0104000 KHANNA HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0104001 11 9, SHIVKUMAR KHANNA SARANI TO KOLKATA – 700015 0104350 KHANNA HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) SUB-CENTRE 'B'; 0104351 12 9, SHIVKUMAR KHANNA SARANI TO KOLKATA - 700015 0104700 BELEGHATA SANTI SANGHA VIDYAYATAN FOR GIRLS 0104701 13 1/8, BAROWARITALA ROAD TO KOLKATA - 700010 0105250 BELEGHATA DESHBANDHU HIGH SCHOOL (BR.) 0105251 14 17/2E, BELEGHATA MAIN ROAD TO KOLKATA – 700010 0105700 BAGMARI MANIKTALA GOVT. -

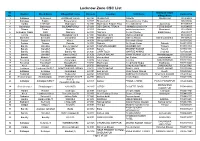

Lucknow Zone CSC List.Xlsx

Lucknow Zone CSC List Sl. Grampanchayat District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No No. Village Name 1 Sultanpur Sultanpur4 JAISINGHPUR(R) 228125 ISHAQPUR DINESH ISHAQPUR 730906408 2 Sultanpur Baldirai Bhawanighar 227815 Bhawanighar Sarvesh Kumar Yadav 896097886 3 Hardoi HARDOI1 Madhoganj 241301 Madhoganj Bilgram Road Devendra Singh Jujuvamau 912559307 4 Balrampur Balrampur BALRAMPUR(U) 271201 DEVI DAYAL TIRAHA HIMANSHU MISHRA TERHI BAZAR 912594555 5 Sitapur Sitapur Hargaon 261121 Hargaon ashok kumar singh Mumtazpur 919283496 6 Ambedkar Nagar Bhiti Naghara 224141 Naghara Gunjan Pandey Balal Paikauli 979214477 7 Gonda Nawabganj Nawabganj gird 271303 Nawabganj gird Mahmood ahmad 983850691 8 Shravasti Shravasti Jamunaha 271803 MaharooMurtiha Nafees Ahmad MaharooMurtiha 991941625 9 Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 10 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 11 Bareilly Bareilly2 Bareilly Npp(U) 243201 TALPURA BAHERI JASVEER GIR Talpura 7037003700 12 Bareilly Bareilly3 Kyara(R) 243001 Kareilly BRIJESH KUMAR Kareilly 7037081113 13 Bareilly Bareilly5 Bareilly Nn 243003 CHIPI TOLA MAHFUZ AHMAD Chipi tola 7037260356 14 Bareilly Bareilly1 Bareilly Nn(U) 243006 DURGA NAGAR VINAY KUMAR GUPTA Nawada jogiyan 7037769541 15 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 16 Faizabad Faizabad5 Askaranpur 224204 Askaranpur Kanchan ASKARANPUR 7052115061 17 Faizabad Faizabad2 Mosodha(R) 224201 Madhavpur Deepchand Gupta Madhavpur -

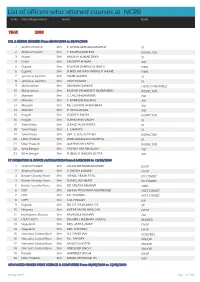

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Complete List of Venues of West Bengal Civil

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. P. MUKHERJEE ROAD, KOLKATA - 700 026 WEST BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE (EXE.) ETC. (PRELI.) EXAMINATION, 2020 Date of Examination : 9TH FEBRUARY, 2020 (SUNDAY) Subject : General Studies Time of Examination : 12:00 NOON TO 2:30 P.M. KOLKATA (NORTH) (01) Sl. Name of the Venues No. of Regd. Candts. Roll Nos. No. DUM DUM ROAD GOVT. SPOND. HIGH SCHOOL FOR GIRLS (H.S.) SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0100001 1 16, DUM DUM ROAD, 300 TO KOLKATA - 700030 0100300 DUM DUM ROAD GOVT. SPOND. HIGH SCHOOL FOR GIRLS (H.S.) SUB-CENTRE 'B' 0100301 2 16, DUM DUM ROAD, 288 TO KOLKATA - 700030 0100588 DUM DUM KUMAR ASUTOSH INSTITUTION (BR.) 0100589 3 6/1, DUM DUM ROAD 600 TO KOLKATA - 700030 0101188 NARAINDAS BANGUR MEMORIAL MULTIPURPOSE SCHOOL 0101189 4 BANGUR AVENUE, BLOCK-D 324 TO KOLKATA - 700055 0101512 DUM DUM AIRPORT HIGH SCHOOL SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0101513 5 NEW QUARTERS RESIDENTIAL COMPLEX, AIRPORT 348 TO KOLKATA - 700052 0101860 DUM DUM AIRPORT HIGH SCHOOL SUB-CENTRE 'B' 0101861 6 NEW QUARTERS RESIDENTIAL COMPLEX, AIRPORT 456 TO KOLKATA - 700052 0102316 MAHARAJA MANINDRA CHANDRA COLLEGE SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0102317 7 20, RAMKANTO BOSE STREET 292 TO KOLKATA - 700003 0102608 MAHARAJA MANINDRA CHANDRA COLLEGE SUB-CENTRE 'B' 0102609 8 20, RAMKANTO BOSE STREET 288 TO KOLKATA - 700003 0102896 MAHARAJA COSSIMBAZAR POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE 0102897 9 3, NANDALAL BOSE LANE 600 TO KOLKATA - 700003 0103496 BETHUNE COLLEGIATE SCHOOL 0103497 10 181, BIDHAN SARANI 504 TO KOLKATA - 700006 0104000 TOWN SCHOOL, CALCUTTA 0104001 11 33, SHYAMPUKUR STREET 396 TO KOLKATA - 700004 0104396 RAGHUMAL ARYA VIDYALAYA 0104397 12 33C, MADAN MITRA LANE 504 TO KOLKATA - 700006 0104900 ARYA KANYA MAHAVIDYALAYA 0104901 13 20, BIDHAN SARANI, 400 TO KOLKATA - 700006 (NEAR SRIMANI MARKET) 0105300 RANI BHABANI SCHOOL 0105301 14 PLOT-1, CIT SCHEME, LXIV, GOA BAGAN 300 TO KOLKATA - 700006 0105600 KHANNA HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) 0105601 15 9, SHIBKUMAR KHANNA SARANI 588 TO KOLKATA - 700015 0106188 THE PARK INSTITUTION SUB-CENTRE 'A' 0106189 16 12, MOHANLAL STREET, P.O. -

Col Col CW-2 DRAFT GAZETTE of INDIA

DRAFT GAZETTE OF INDIA (EXTRAORDINARY) PART I - SECTION 4 (ARMY BRANCH) B/43432/RD20/AG/CW-2 New Delhi, the 26 January 2020 No. 03(E) dated 26 January 2020. The President is pleased to grant honorary rank of Naib Risaldar/Subedar to the under mentioned NCOs on the eve of Republic Day 2020 under Para 180 of the Regulation for the Army 1987, with effect from the dates shown against their names:- TO BE NAIB RISALDAR/SUBEDAR (ON RETIREMENT) ARMOURED CORPS 1 15469382A DFR ABUL KLAM 01-01-2020 2 15468895H DFR AMAR SINGH 01-09-2019 3 15469530A DFR ANUJ KUMAR DESHMUKH 01-01-2020 4 15462589X DFR ASHOK KUMAR 01-09-2019 5 15469378X DFR ASHOK KUMAR 01-01-2020 6 15468921Y DFR BALJINDER SINGH 01-09-2019 7 15469254H DFR BANJIT MEDHI 01-11-2019 8 15462776W DFR BANSI LAL 01-11-2019 9 15462945M DFR BELAL AHMAD 01-11-2019 10 15463026K DFR BHAGWAN SINGH RATHORE 01-01-2020 11 15468934W DFR BHAIKON DUWARAH 01-09-2019 12 15469214F DFR BHANWAR SINGH KHICHI 01-11-2019 13 15468973P DFR BHANWARU KHAN 01-09-2019 14 15469564N DFR BHOM SINGH RATHORE 01-01-2020 15 15469593H DFR BISHWA NATH PRASAD 01-01-2020 16 15463643M DFR BISWAJIT DUTTA 01-01-2020 17 15468925P DFR BRAJEN SAIKIA 01-09-2019 18 15468910M DFR BRAJESH KUMAR 01-09-2019 19 15469463A DFR BRIJ KISHORE 01-01-2020 20 15462738A DFR BRIMHA SINGH 01-11-2019 21 15469049F DFR CHAMAN LAL 01-09-2019 22 15469256N DFR CHAMPAK ROY 01-11-2019 23 15469311Y DFR DAMODAR KUMAR 01-12-2019 24 15468872F DFR DARSAN PAL SINGH 01-09-2019 25 15469559H DFR DESHMUKH KALYAN RUSTUM 01-01-2020 26 15462962M DFR DEVENDRA PRATAP SINGH 01-12-2019 -

ALLAHABAD BANK PERSONNEL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT Head Office: 2 N

ALLAHABAD BANK PERSONNEL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT Head Office: 2 N. S. Road, Kolkata – 700 001 Instruction Circular No. 17302/HO/PA/2019-20/125 Date: 31/03/2020 To All Offices & Branches C I R C U L A R Allotment of new SR number The central government has come out with a scheme called “The Amalgamation of Allahabad Bank into Indian Bank Scheme, 2000” vide notification No. G.S.R. 156 (E) dated 04.03.2020 published in the Gazette of India Extraordinary No.133 dated 04.03.2020, whereby Allahabad Bank is to be amalgamated into Indian Bank w.e.f. 01st April, 2020. In view of the above, all the employees of Allahabad Bank in active service as also those who have retired from Allahabad Bank as on 01.04.2020 have been allotted with NEW SR NUMBER replacing existing Employee No/PF No w.e.f. 01.04.2020. The list of new SR numbers is enclosed in annexure I & II. Annexure-I : SR Number of the employees in active service. Annexure-II : SR Number of the retired employees However, the existing employee No./ PF No. will remain functional till further instruction. All concerned are requested to take a careful note of their respective SR Number as per the Annexure. Hindi version of the circular will follow. (S.K. Suri) General Manager (HR) Annexure-II: SR Number of the retired employees SNO PF_No Pensioner_name New SR No 1 24 P K DASGUPTA 400024 2 46 GANESH PRASAD TANDON 400046 3 57 SHAYAMAL KUMAR SANYAL 400057 4 61 RAM MURAT MISHRA 400061 5 68 RAMESH CHANDRA SRIVASTAVA 400068 6 69 SRI PRAKASH MISHRA 400069 7 71 SUDARSHAN KUMAR KHANNA 400071 8 84 SARAN KUMAR 400084 9 89 CHITTA RANJAN BASU 400089 10 92 DEB KUMAR BANERJEE 400092 11 93 GOPI NATH SETH 400093 12 96 NEMAI CHANDRA DEY 400096 13 100 P N.S. -

Complete List of Venues and Assigned Range of Roll Numbers of Clerkship Examination

PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, WEST BENGAL 161-A, S. P. MUKHERJEE ROAD, KOLKATA - 700 026 CLERKSHIP EXAMINATION (PART -I), 2019 Date of Examination : 25TH JANUARY, 2020 (SATURDAY) Subject : General Studies Time of Examination : 10:00 A.M. TO 11:30 A.M. & 2:00 P.M. TO 3:30 P.M. Name of Centre : ASANSOL (11) STD Code : 0341 Sl. Name of the Venues No. of Roll Nos. Roll Nos. No. Regd. (Forenoon (Afternoon Candts. Session) Session) D.A.V. HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) 1100001 1110371 1 BUDHA, P.O. ASANSOL,(NEAR HUTTON ROAD, RAMDHANI MORE) 500 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BURDWAN-713301 1100500 1110870 BIDHAN SMRITY SIKSHA NIKETAN (H.S.) 1100501 1110871 2 VILL. & P.O. DAMRA, PS-ASANSOL SOUTH 300 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BURDWAN - 713339 (NEAR JORA KALI MANDIR) 1100800 1111170 USHAGRAM GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL (H.S.) 1100801 1111171 3 G.T.ROAD, ASANSOL(OPP: B.B.COLLEGE) 450 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BARDHAMAN - 713 303 1101250 1111620 SANTINAGAR VIDYAMANDIR (H.S.) 1101251 1111621 4 SANTINAGAR, P.O. BURNPUR (NEAR BURNPUR BUS STAND), 360 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BURDWAN - 713325 1101610 1111980 RAHMATNAGAR HIGH SCHOOL (URDU) 1101611 1111981 5 RAHMATNAGAR, P.O. BURNPUR (NEAR RAHMATNAGAR MAZJID) 480 TO TO DIST. PASCHIM BARDHAMAN - 713 325 1102090 1112460 ARYA KANYA UCHCHA VIDYALAYA (H.S.) 1102091 1112461 6 MURGASAL, NEAR - ARYA KANYA SCHOOL RD. 480 TO TO ASANSOL - 713303 1102570 1112940 ASANSOL DAYANAND VIDYALAYA (H.S.) 1102571 1112941 7 D.A.V.SCHOOL RD., BUDHA, ASANSOL 650 TO TO PIN - 713301 (NEAR D.A.V. HIGH SCHOOL) 1103220 1113590 SUBHASPALLI BIDYANIKETAN (H.S.) 1103221 1113591 8 SUBHAS PALLI MAIN ROAD, P.O. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

THE MILITIA MOVEMENT IN BANGLADESH Ideology, Motivation, Mobilization, Organization, and Ritual by AMM Quamruzzaman A thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada May, 2010 Copyright © AMM Quamruzzaman 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70060-0 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-70060-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Paper Download

Culture survival for the indigenous communities with reference to North Bengal, Rajbanshi people and Koch Bihar under the British East India Company rule (1757-1857) Culture survival for the indigenous communities (With Special Reference to the Sub-Himalayan Folk People of North Bengal including the Rajbanshis) Ashok Das Gupta, Anthropology, University of North Bengal, India Short Abstract: This paper will focus on the aspect of culture survival of the local/indigenous/folk/marginalized peoples in this era of global market economy. Long Abstract: Common people are often considered as pre-state primitive groups believing only in self- reliance, autonomy, transnationality, migration and ancient trade routes. They seldom form their ancient urbanism, own civilization and Great Traditions. Or they may remain stable on their simple life with fulfillment of psychobiological needs. They are often considered as serious threat to the state instead and ignored by the mainstream. They also believe on identities, race and ethnicity, aboriginality, city state, nation state, microstate and republican confederacies. They could bear both hidden and open perspectives. They say that they are the aboriginals. States were in compromise with big trade houses to counter these outsiders, isolate them, condemn them, assimilate them and integrate them. Bringing them from pre-state to pro-state is actually a huge task and you have do deal with their production system, social system and mental construct as well. And till then these people love their ethnic identities and are in favour of their cultural survival that provide them a virtual safeguard and never allow them to forget about nature- human-supernature relationship: in one phrase the way of living. -

Chapter·: 2 Colonial Physical Setting

i Chapter·: 2 Colonial Physical Setting 9 Chaptel": 2 Colonial Physical Setting The colonial stall~ is'·a basic part ul' the colonial structure. The basic character of colonialism and its differeilt stages can be illustrated fl·om the historJ of colonialism in modern India. 1J)iS is specially so hecause historians agrL'C on treating India as a classic colony~ The basic character of British rul_c d1d not renwin the same through its l~ng history of nearly two hundred years. Indian colonialism can be termed as the period of 'monopoly trade and direct apj1ropriation. "The L':lrly days or the British pmv·cr in India were the days· of merchant advcntun:rs \vho tralkd and plundL·•·cd indiscriminatdy. ·I The East India Company aqd its agents l"arriL·d niT in this \\:1)' a vast amount of tht.: accumulated wealth of India. The company was a trading conc~:rn and its main object was to promote commerce and make profit. 2 During the first period of British rule, in the second half of the eighteenth century. the entire pro lit went one way - to En~land. The second period cov~:red the nineteenth century. \\hL·n India bL'Camc. at the same time, a great soun.:c for raw m'aterials !'or the bctorie~: ol' l·:ngland. and a 1narkct for British manufactured goods. This was done r,t the c:-;pense o!' India's progress and economic development. Hence it took o•1ly such interest in political am! administrative matters as was necessary for tl1c promotion of its commL·I-cial interest.