Introducing Studio Ghibli James Rendell and Rayna Denison Many

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEEK 30: Sunday, 21 July

WEEK 30: Sunday, 21 July - Saturday, 27 July 2019 ALL MARKETS Start Consumer Closed Date Genre Title TV Guide Text Country of Origin Language Year Repeat Classification Subtitles Time Advice Captions Gorgeously animated, this wordless story about a stranded castaway pays Studio 2019-07-21 0600 Animation The Red Turtle tribute to what's most important in life: companionship, love, family, and the JAPAN No Dialogue-100 2016 RPT PG Ghibli stewardship of nature. One day, while spending the summer with her great aunt, Mary follows an odd cat into the nearby woods. There she stumbles upon flowers which hold a Studio 2019-07-21 0730 Fantasy Mary And The Witch's Flower strange, luminescent power that brings a broomstick to life - which then, in a JAPAN English-100 2017 RPT PG Ghibli heartbeat, whisks her above the clouds and off to a strange and secret place. It is here she finds Endor College - a school of magic! When master thief Lupin III discovers that the money he robbed from a casino is counterfeit, he goes to Cagliostro, rumoured to be the source of the forgery. Studio 2019-07-21 0930 Family The Castle Of Cagliostro There he discovers a beautiful princess, Clarisse, who's being forced to marry JAPAN English-100 1979 RPT PG Y Ghibli the count. In order to rescue Clarisse and foil the count, Lupin teams up with his regular adversary, Inspector Zenigata, and fellow thief Fujiko Mine. Set in Yokohama in 1963, this lovingly hand-drawn film centers on Umi (voiced by Sarah Bolger) and Shun (voiced by Anton Yelchin) and the budding romance that develops as they join forces to save their high school’s ramshackle Studio 2019-07-21 1130 Drama From Up On Poppy Hill clubhouse from demolition. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

(WHEN MARNIE WAS THERE) Is a Fourth Quarter 2017 LVCA Dvd

OMOIDE NO MÂNÎ (WHEN MARNIE WAS THERE) is a Fourth Quarter 2017 LVCA dvd donation to the Hugh Stouppe Memorial Library of the Heritage United Methodist Church of Ligonier, Pennsylvania. Here’s Kino Ken’s review of that mystical animation from Japan. 16 of a possible 20 points **** of a possible ***** Japan 2014 color 103 minutes feature animation fantasy dubbed in English Studio Ghibli / Toho Company /Dentsu / Hakuhodo DY Media Partners Producers: Yoshiaki Nishimura, Koji Hoshino, Geoffrey Wexler (English version), Toshio Suzuki Key: *indicates outstanding technical achievement or performance (j) designates a juvenile performer Points: Direction: Hiromasa Yonebayashi 0 Editing: Rie Matsubara 2 Photography: Atsushi Okui 2 Lighting 2 Animation: Masashi Ando (Animation Director) 1 Screenplay: Keiko Niwa, Masashi Ando, and Hiromasa Yonebayashi based on the novel by Joan Robinson 2 Music: Takatsugu Muramatsu, Priscilla Ahn (theme music) Francisco Tarriega (“Valse in La Mayor” from Recuerdos de la Alhambra) 2 Production Design: Yohei Taneda Character Design: Masashi Ando 2 Sound: Eriko Kimura, Jamie Simone (English Version) Sound Direction: Koji Kasamatsu 1 Voices Acting 2 Creativity 16 total points English Voices Cast: Ava Acres (Sayaka), Kathy Bates (Mrs. Kadoya), Taylor Autumn Bertman (j) (Young Marnie), Mila Brener (j) (Young Hisako), Ellen Burstyn (Nan), Geena Davis (Yoriko Sasaki), Grey Griffin (Setsu Oiwa), Catherine O’Hara (Elderly Lady), Takuma Oroo (Neighborhood Association Officer), John Reilly (Kiyomasa Oiwa), Raini Rodriguez (Nobuko -

Hayao Miyazaki Film

A HAYAO MIYAZAKI FILM ORIGINAL STORY AND SCREENPLAY WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY HAYAO MIYAZAKI MUSIC BY JOE HISAISHI THEME SONGS PERFORMED BY MASAKO HAYASHI AND FUJIOKA FUJIMAKI & NOZOMI OHASHI STUDIO GHIBLI NIPPON TELEVISION NETWORK DENTSU HAKUHODO DYMP WALT DISNEY STUDIOS HOME ENTERTAINMENT MITSUBISHI AND TOHO PRESENT A STUDIO GHIBLI PRODUCTION - PONYO ON THE CLIFF BY THE SEA EXECUTIVE PRODUCER KOJI HOSHINO PRODUCED BY TOSHIO SUZUKI © 2008 Nibariki - GNDHDDT Studio Ghibli, Nippon Television Network, Dentsu, Hakuhodo DYMP, Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment, Mitsubishi and Toho PRESENT PONYO ON THE CLIFF BY THE SEA WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY HAYAO MIYAZAKI Running time: 1H41 – Format: 1.85:1 Sound: Dolby Digital Surround EX - DTS-ES (6.1ch) INTERNATIONAL PRESS THE PR CONTACT [email protected] Phil Symes TEL 39 346 336 3406 Ronaldo Mourao TEL +39 346 336 3407 WORLD SALES wild bunch Vincent Maraval TEL +33 6 11 91 23 93 E [email protected] Gaël Nouaille TEL +33 6 21 23 04 72 E [email protected] Carole Baraton / Laurent Baudens TEL +33 6 70 79 05 17 E [email protected] Silvia Simonutti TEL +33 6 20 74 95 08 E [email protected] PARIS OFFICE 99 Rue de la Verrerie - 75004 Paris - France TEL +33 1 53 01 50 30 FAX +33 1 53 01 50 49 [email protected] PLEASE NOTE: High definition images can be downloaded from the ‘press’ section of http://www.wildbunch.biz SYNOPSIS CAST A small town by the sea. Lisa Tomoko Yamaguchi Koichi Kazushige Nagashima Five year-old Sosuke lives high on a cliff overlooking Gran Mamare Yuki Amami the Inland Sea. -

A Voice Against War

STOCKHOLMS UNIVERSITET Institutionen för Asien-, Mellanöstern- och Turkietstudier A Voice Against War Pacifism in the animated films of Miyazaki Hayao Kandidatuppsats i japanska VT 2018 Einar Schipperges Tjus Handledare: Ida Kirkegaard Innehållsförteckning Annotation ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aim of the study ............................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Material ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Research question .......................................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Theory ........................................................................................................................................... 5 1.4.1 Textual analysis ...................................................................................................................... 5 1.4.2 Theory of animation, definition of animation ........................................................................ 6 1.5 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ -

Joe Hisaishi's Musical Contributions to Hayao Miyazaki's Animated Worlds

Joe Hisaishi’s musical contributions to Hayao Miyazaki’s Animated Worlds A Division III Project By James Scaramuzzino "1 Hayao Miyazaki, a Japanese film director, producer, writer, and animator, has quickly become known for some of the most iconic animated films of the late twentieth to early twenty first century. His imaginative movies are known for fusing modern elements with traditional Japanese folklore in order to explore questions of change, growth, love, and home. His movies however, would, not be what they are today without the partnership he formed early in his career with Mamoru Fujisawa a music composer who goes by the professional name of Joe Hisaishi. Their partnership formed while Hayao Miyazaki was searching for a composer to score his second animated feature film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). Hi- saishi had an impressive resume having graduated from Kunitachi College of Music, in addition to studying directly under the famous film composer Masaru Sato who is known for the music in Seven Samurai and early Godzilla films. Hisaishi’s second album, titled Information caught the attention of Miyazaki, and Hisaishi was hired to score Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). With its huge success consequently every other prom- inent movie of Miyazaki’s since. (Koizumi, Kyoko. 2010) Hisaishi’s minimalistic yet evocative melodies paired with Miyazaki’s creative im- agery and stories proved to be an incredible partnership and many films of theirs have been critically acclaimed, such as Princess Mononoke (1997), which was the first ani- mated film to win Picture of the Year at the Japanese Academy Awards; or Spirited Away (2001), which was the first anime film to win an American Academy Award. -

Tesis.Pdf (13.00Mb)

Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas Escuela Internacional de Doctorado 2018 TESIS DOCTORAL Lidia Esteban López Sofia López Hernández, Mario Rajas Fernández y Eduardo Rodríguez Merchán Antonio Sánchez-Escalonilla García-Rico En el transcurso de los últimos dos años han fallecido dos apasionados de la música y el cine sin los que esta tesis hubiera sido completamente distinta. A uno de ellos nunca llegué a conocerlo, al menos no más allá de lo que uno puede conocer a alguien a través de su obra. Se trata de Isao Takahata, protagonista de las próximas páginas. Con el otro sí tuve la fortuna de coincidir. Eduardo Rodríguez Merchán, director inicial de este trabajo de investigación, me dijo que hablara de música, quiso que analizara las películas que más me gustaban (“si estás dispuesta a aprender japonés...”). Pero además fue espectador de mis conciertos, y compartió su sonrisa cálida y sus consejos cercanos en tardes de merienda y cine. No puedo por menos que agradecer enteramente esta tesis a un amigo. I. INTRODUCCIÓN ............................................................................ 1 1. Elección del tema de investigación ............................................ 1 2. Introducción a Studio Ghibli ...................................................... 5 3. Proceso de producción y conceptos básicos ............................ 11 II. METODOLOGÍA ........................................................................... 17 1. Objetivos ................................................................................ -

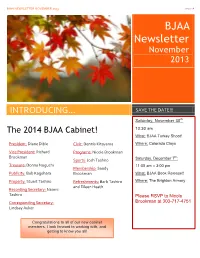

BJAA NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER 2013 Issue

BJAA NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER 2013 Issue # BJAA Newsletter November 2013 INTRODUCING… SAVE THE DATE!!! th: Saturday, November 30 10:30 am The 2014 BJAA Cabinet! What: BJAA Turkey Shoot! President: Diane Dible Civic: Dennis Kitayama Where: Colorado Clays Vice President: Richard Programs: Nicole Brookman Brookman th Sports: Josh Tashiro Saturday, December 7 : Treasure: Donna Noguchi 11:00 am – 3:00 pm Membership: Sandy Publicity: Bob Kagohara Brookman What: BJAA Book Release!! Property: Stuart Tashiro Refreshments: Barb Tashiro Where: The Brighton Armory and Eileen Heath Recording Secretary: Naomi Tashiro Please RSVP to Nicole Corresponding Secretary: Brookman at 303-717-4751 Lindsay Auker Congratulations to all of our new cabinet members, I look forward to working with, and getting to know you all! BJAA NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER 2013 | Issue # 2 BJAA TURKEY SHOOT! It’s Turkey Time! That means it's time for our annual Turkey Shoot. The Turkey Shoot will be taking place on November 30th at 10:30 am at Colorado Clays. If you don't have a rifle, they can be rented at the clubhouse. The BJAA will pay for clays for members, but please bring your own shells. This event will be pot luck style, so please bring a dish for everyone to enjoy. If you are not familiar with Colorado Clays, please find their Please RSVP to Nicole address and phone number below. Brookman if you plan on Colorado Clays attending the Turkey Shoot. 13600 Lanewood St, Brighton, CO 80603 You can reach Nicole at: (303) 659-7117 303-717-4751 BJAA BOOK RELEASE!! We have an EXTREMELY exciting event planned that I encourage everyone to attend (and spread the word to other members and friends as well!) On December 7th we will be celebrating the premier of "Our American Journey: A History of the Brighton Nisei Women's Club and the Brighton Japanese American Association" by Daniel Blegen. -

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: a Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: A Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 25–40. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 01:01 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 25 Chapter 1 P RINCESS MONONOKE : A GAME CHANGER Shiro Yoshioka If we were to do an overview of the life and works of Hayao Miyazaki, there would be several decisive moments where his agenda for fi lmmaking changed signifi cantly, along with how his fi lms and himself have been treated by the general public and critics in Japan. Among these, Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke , 1997) and the period leading up to it from the early 1990s, as I argue in this chapter, had a great impact on the rest of Miyazaki’s career. In the fi rst section of this chapter, I discuss how Miyazaki grew sceptical about the style of his fi lmmaking as a result of cataclysmic changes in the political and social situation both in and outside Japan; in essence, he questioned his production of entertainment fi lms featuring adventures with (pseudo- )European settings, and began to look for something more ‘substantial’. Th e result was a grave and complex story about civilization set in medieval Japan, which was based on aca- demic discourses on Japanese history, culture and identity. -

"Deer Gods, Nativism and History: Mythical and Archaeological Layers in Princess Mononoke." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Niskanen, Eija. "Deer Gods, Nativism and History: Mythical and Archaeological Layers in Princess Mononoke." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 41–56. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 8 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 8 October 2021, 10:51 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. Released under a CC BY-NC-ND licence (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 41 Chapter 2 D EER GODS, NATIVISM AND HISTORY: MYTHICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL LAYERS IN PRINCESS MONONOKE E i j a N i s k a n e n I n Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke , 1997) Hayao Miyazaki depicts the main character, Prince Ashitaka, as a son of the Emishi nation, one of Japan’s van- ished native tribes, who inhabited West- Northern Japan before the Eastern- Southern Yamato nation took control, starting in the area that is now the basis for modern Japan before claiming the entire country. Emishi, similar to the other native tribes of Northern Japan are oft en seen as non- civilized barbar- ians as opposed to the Yamato race. 1 Th ough Princess Mononoke is set in the Muromachi period (1333– 1573), when the Yamato society had conquered all the Northern tribes, the strong Emishi village of Princess Mononoke recalls Japan’s pre- historic times. In the fi lm’s settings and details one can fi nd numer- ous examples of Miyazaki’s interest in anthropology, archaeology, Shint ō and nativism. -

Fall/Winter 2018

FALL/WINTER 2018 Yale Manguel Jackson Fagan Kastan Packing My Library Breakpoint Little History On Color 978-0-300-21933-3 978-0-300-17939-2 of Archeology 978-0-300-17187-7 $23.00 $26.00 978-0-300-22464-1 $28.00 $25.00 Moore Walker Faderman Jacoby Fabulous The Burning House Harvey Milk Why Baseball 978-0-300-20470-4 978-0-300-22398-9 978-0-300-22261-6 Matters $26.00 $30.00 $25.00 978-0-300-22427-6 $26.00 Boyer Dunn Brumwell Dal Pozzo Minds Make A Blueprint Turncoat Pasta for Societies for War 978-0-300-21099-6 Nightingales 978-0-300-22345-3 978-0-300-20353-0 $30.00 978-0-300-23288-2 $30.00 $25.00 $22.50 RECENT GENERAL INTEREST HIGHLIGHTS 1 General Interest COVER: From Desirable Body, page 29. General Interest 1 The Secret World Why is it important for policymakers to understand the history of intelligence? Because of what happens when they don’t! WWI was the first codebreaking war. But both Woodrow Wilson, the best educated president in U.S. history, and British The Secret World prime minister Herbert Asquith understood SIGINT A History of Intelligence (signal intelligence, or codebreaking) far less well than their eighteenth-century predecessors, George Christopher Andrew Washington and some leading British statesmen of the era. Had they learned from past experience, they would have made far fewer mistakes. Asquith only bothered to The first-ever detailed, comprehensive history Author photograph © Justine Stoddart. look at one intercepted telegram. It never occurred to of intelligence, from Moses and Sun Tzu to the A conversation Wilson that the British were breaking his codes. -

"Introducing Studio Ghibli's Monster Princess: from Mononokehime To

Denison, Rayna. "Introducing Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess: From Mononokehime to Princess Mononoke." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 1–20. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 6 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 6 October 2021, 08:10 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 I NTRODUCING STUDIO GHIBLI’S MONSTER PRINCESS: FROM M ONONOKEHIME TO P RINCESS MONONOKE Rayna Denison When it came out in 1997, Hayao Miyazaki’s Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke ) was a new kind of anime fi lm. It broke long- standing Japanese box offi ce records that had been set by Hollywood fi lms, and in becoming a blockbuster- sized hit Mononokehime demonstrated the commercial power of anime in Japan.1 F u r t h e r , Mononokehime became the fi rst of Miyazaki’s fi lms to benefi t from a ‘global’ release thanks to a new distribution deal between Disney and Tokuma shoten, then the parent company for Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli. As a result of this deal, Mononokehime was transformed through translation: US star voices replaced those of Japanese actors, a new market- ing campaign reframed the fi lm for US audiences and famous fantasy author Neil Gaiman undertook a localization project to turn Mononokehime into Princess Mononoke (1999). 2 A s Princess Mononoke, it was the fi rst Miyazaki fi lm to receive a signifi cant cinematic release in the United States.