“Bud” Brown Jr. Oral History Interviews Final Edited Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Universe of Tom

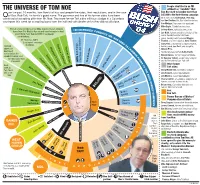

People identified in an FBI THE UNIVERSE OF TOM NOE ■ affidavit as “conduits” that ver the past 10 months, Tom Noe’s fall has cost people their jobs, their reputations, and in the case Tom Noe used to launder more than Oof Gov. Bob Taft, his family’s good name. The governor and two of his former aides have been $45,000 to the Bush-Cheney campaign: convicted of accepting gifts from Mr. Noe. Two more former Taft aides will face a judge in a Columbus MTS executives Bart Kulish, Phil Swy, courtroom this week for accepting loans from the indicted coin dealer which they did not disclose. and Joe Restivo, Mr. Noe’s brother-in-law. Sue Metzger, Noe executive assistant. Mike Boyle, Toledo businessman. Five of seven members of the Ohio Supreme Court stepped FBI-IDENTIF Jeffrey Mann, Toledo businessman. down from The Blade’s Noe records case because he had IED ‘C OND Joe Kidd, former executive director of the given them more than $20,000 in campaign UIT S’ M Lucas County board of elections. contributions. R. N Lucas County Commissioner Maggie OE Mr. Noe was Judith U Thurber, and her husband, Sam Thurber. Lanzinger’s campaign SE Terrence O’Donnell D Sally Perz, a former Ohio representative, chairman. T Learned Thomas Moyer O her husband, Joe Perz, and daughter, Maureen O’Connor L about coin A U Allison Perz. deal about N D Toledo City Councilman Betty Shultz. a year before the E Evelyn Stratton R Donna Owens, former mayor of Toledo. scandal erupted; said F Judith Lanzinger U H. -

Frontier Knowledge Basketball the Map to Ohio's High-Tech Future Must Be Carefully Drawn

Beacon Journal | 12/29/2003 | Fronti... Page 1 News | Sports | Business | Entertainment | Living | City Guide | Classifieds Shopping & Services Search Articles-last 7 days for Go Find a Job Back to Home > Beacon Journal > Wednesday, Dec 31, 2003 Find a Car Local & State Find a Home Medina Editorial Ohio Find an Apartment Portage Classifieds Ads Posted on Mon, Dec. 29, Stark 2003 Shop Nearby Summit Wayne Sports Baseball Frontier knowledge Basketball The map to Ohio's high-tech future must be carefully drawn. A report INVEST YOUR TIME Colleges WISELY Football questions directions in the Third Frontier Project High School Keep up with local business news and Business information, Market Arts & Living Although voters last month rejected floating bonds to expand the updates, and more! Health state's high-tech job development program, the Third Frontier Project Food The latest remains on track to spend more than $100 million a year over the Enjoy in business Your Home next decade. The money represents a crucial investment as Ohio news Religion weathers a painful economic transition. A new report wisely Premier emphasizes the existing money must be spent with clear and realistic Travel expectations and precise accountability. Entertainment Movies Music The report, by Cleveland-based Policy Matters Ohio, focuses only on Television the Third Frontier Action Fund, a small but long-running element of Theater the Third Frontier Project. The fund is expected to disburse $150 US & World Editorial million to companies, universities and non-profit research Voice of the People organizations. Columnists Obituaries It has been up and running since 1998, under the administration of Corrections George Voinovich. -

Senator Dole FR: Kerry RE: Rob Portman Event

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu TO: Senator Dole FR: Kerry RE: Rob Portman Event *Event is a $1,000 a ticket luncheon. They are expecting an audience of about 15-20 paying guests, and 10 others--campaign staff, local VIP's, etc. *They have asked for you to speak for a few minutes on current issues like the budget, the deficit, and health care, and to take questions for a few minutes. Page 1 of 79 03 / 30 / 93 22:04 '5'561This document 2566 is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas 141002 http://dolearchives.ku.edu Rob Portman Rob Portman, 37, was born and raised in Cincinnati, in Ohio's Second Congressional District, where he lives with his wife, Jane. and their two sons, Jed, 3, and Will~ 1. He practices business law and is a partner with the Cincinnati law firm of Graydon, Head & Ritchey. Rob's second district mots run deep. His parents are Rob Portman Cincinnati area natives, and still reside and operate / ..·' I! J IT ~ • I : j their family business in the Second District. The family business his father started 32 years ago with four others is Portman Equipment Company headquartered in Blue Ash. Rob worked there growing up and continues to be very involved with the company. His mother was born and raised in Wa1Ten County, which 1s now part of the Second District. Portman first became interested in public service when he worked as a college student on the 1976 campaign of Cincinnati Congressman Bill Gradison, and later served as an intern on Crradison's staff. -

To the Assembled Members of the Judiciary, Dignitaries from the Other

To the assembled members of the Judiciary, dignitaries from the other branches of the government, esteemed members of the bar, and other welcomed guests, I am Judge Ronald Adrine, and it is my honor to currently serve as the Administrative and Presiding Judge of the Cleveland Municipal Court. On behalf of my colleagues and the hard-working staff of our court I bring you greetings. Before starting my presentation this afternoon, I take great pleasure in introducing to some and present to others the greatest Municipal Court bench in the country. I will call their names in alphabetical order and ask those of my colleagues who were able to join us today to rise and be recognized. They are: Judge Marilyn Cassidy Judge Pinky Carr Judge Michelle Earley Judge Emanuella Groves Judge Anita Laster Mays Judge Lauren Moore Judge Charles Patton Judge Raymond Pianka Judge Michael Ryan Judge Angela Stokes Judge Pauline Tarver Judge Joseph Zone The judges would also like to recognize Mr. Earle B. Turner, our Clerk of court. In addition, some of our staff have taken time from their lunch hour to participate in this event. I ask that all employees of the court’s General, Housing and Clerk Divisions who are present please stand and be recognized. 1 A wise person once said that, “If you don’t know where you’ve been, it’s hard to know where you are and impossible to know where you are going. In this, our court’s 100th year, I believe that that statement could not be truer. So, those of us who now serve on the court decided to take this time to pause and consider and honor our past, examine our present and to reflect upon our future. -

OHIO HISTORY Etablished in June 1887 As the Ohio Archaeological Volume 113 / Winter-Spring 2004 and Historical Quarterly

OHIO HISTORY Etablished in June 1887 as the Ohio Archaeological Volume 113 / Winter-Spring 2004 and Historical Quarterly www.ohiohistory.org/publications/ohiohistory EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Contents Randall Buchman Defiance College ARTICLES Andrew R. L. Cayton Communication Technology Transforms the Marketplace: 4 Miami University The Effect of the Telegraph, Telephone, and Ticker on the John J. Grabowski Cincinnati Merchants’ Exchange Case Western Reserve by Bradford W. Scharlott University and Western Reserve Historical Society Steubenville, Ohio, and the Nineteenth-Century 18 Steamboat Trade R. Douglas Hurt Iowa State University by Jerry E. Green George W. Knepper University of Akron BOOK REVIEWS Robert M. Mennel University of New Hampshire The Collected Works of William Howard Taft 31 Vol. 5, Popular Government & The Anti-trust Act and the Supreme Zane Miller Court. Edited with commentary by David Potash and Donald F. University of Cincinnati Anderson; Marian J. Morton Vol. 6, The President and His Powers & The United States and John Carroll University Peace. Edited with commentary by W. Carey McWilliams and Frank X. Gerrity. Larry L. Nelson —REVIEWED BY CLARENCE E. WUNDERLIN JR. Ohio Historical Society, Fort Meigs From Blackjacks To Briefcases: A History of Commercialized 32 Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States. By Robert Harry Scheiber Michael Smith. —REVIEWED BY JAMES E. CEBULA. University of California, Berkeley Confronting American Labor: The New Left Dilemma. By Jeffrey W. 33 Coker. —REVIEWED BY TERRY A. COONEY. Warren Van Tine The Ohio State University European Capital, British Iron, and an American Dream: The Story 34 of the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad. By William Reynolds; Mary Young edited by Peter K. -

National Governors' Association Annual Meeting 1977

Proceedings OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEETING 1977 SIXTY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING Detroit. Michigan September 7-9, 1977 National Governors' Association Hall of the States 444 North Capitol Street Washington. D.C. 20001 Price: $10.00 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 12-29056 ©1978 by the National Governors' Association, Washington, D.C. Permission to quote from or to reproduce materials in this publication is granted when due acknowledgment is made. Printed in the United Stales of America CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Standing Committee Rosters vii Attendance ' ix Guest Speakers x Program xi OPENING PLENARY SESSION Welcoming Remarks, Governor William G. Milliken and Mayor Coleman Young ' I National Welfare Reform: President Carter's Proposals 5 The State Role in Economic Growth and Development 18 The Report of the Committee on New Directions 35 SECOND PLENARY SESSION Greetings, Dr. Bernhard Vogel 41 Remarks, Ambassador to Mexico Patrick J. Lucey 44 Potential Fuel Shortages in the Coming Winter: Proposals for Action 45 State and Federal Disaster Assistance: Proposals for an Improved System 52 State-Federal Initiatives for Community Revitalization 55 CLOSING PLENARY SESSION Overcoming Roadblocks to Federal Aid Administration: President Carter's Proposals 63 Reports of the Standing Committees and Voting on Proposed Policy Positions 69 Criminal Justice and Public Protection 69 Transportation, Commerce, and Technology 71 Natural Resources and Environmental Management 82 Human Resources 84 Executive Management and Fiscal Affairs 92 Community and Economic Development 98 Salute to Governors Leaving Office 99 Report of the Nominating Committee 100 Election of the New Chairman and Executive Committee 100 Remarks by the New Chairman 100 Adjournment 100 iii APPENDIXES I Roster of Governors 102 II. -

Extensions of Remarks E839 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

June 16, 2017 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E839 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS HONORING MICHAEL DILLABOUGH, PERSONAL EXPLANATION by $800 billion. Trump proposes another $600 ON THE OCCASION OF HIS RE- billion from Medicaid in his budget. TIREMENT HON. JASON LEWIS Almost 2 million veterans and 660,000 vet- OF MINNESOTA erans spouses rely on Medicaid for their IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES health services. In my home state of Alabama, HON. JARED HUFFMAN around 28,000 veterans are enrolled in Med- Friday, June 16, 2017 icaid. According to a study by the Urban Insti- OF CALIFORNIA Mr. LEWIS of Minnesota. Mr. Speaker, on tute, the rate of uninsured veterans fell by 42 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES June 13, 2017, during Roll Call Vote No. 306 percent between 2013 and 2015. on the passage of H.R. 2581, the Verify First States that expanded Medicaid saw a 34 Friday, June 16, 2017 Act, I was recorded as not voting. Although I percent increase in the number of Medicaid- Mr. HUFFMAN. Mr. Speaker, I rise today was present on the floor at the time, my vote enrolled veterans, whereas states that de- was misreported, and I fully intended to vote with my colleague Congressman MIKE THOMP- clined the expansion saw a 3 percent in- ‘‘Yes’’ on Roll Call Vote No. 306. SON in recognition of Michael Dillabough, as crease. In Alabama, percent about 13,000 un- he retires from the United States Army Corps f insured Veterans would have qualified for health coverage had the state expanded. The of Engineers after a stellar 23-year career. -

Roosevelt /W Inner Democrats Captnre

Hit Weather ForeeMt of U. S. Weather BursMi Evrnina RMafit Fslr, mnrh colder tonight; iG E TWELVE Thiirsdsy fair and colder. 127,000 Local Manchester— A City of VUlage (:harm Emergency Doctors Porter St. Residents HALE'S SELF SERVE PRICE THREE CENI'S Novel Staging (EIGHTEEN PAGES) About Town Voting Units] The OriKlnal In New’EnRland! MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 1940 Physicians of the Manchc.stcr O f Style Show Medical Association who Ask Walks, Policeman respond to emergency calls AND HEALTH MARKET morrow afternoon are Df- Different Word Than I nin» » t 8 o'clock at »<eadq»iarter«, Howard Boyd and rir. Rdmun^l C. I., of C. to Elim inate clal conat&bl* on Caae Brothers Precinct to Be Used in | Appear Before Select Spruce' street. Zaglio. _____ The Regulation Parade property wa« voted. Wed. Morning Specials men to Request Protec On requeat of the developers, Few States. ^ Mr. and Mrs. George ^ ^ r of Tomorrow Evening. the Board \»ted to call shortly a HrK. Green Stamps Given WltjK^ash Sales. The Sewing Circle of the Arneri- tion for Children Dur hearing on the ' acceptance of Washington, Nov. 6—(IPl — The I 173 Wetherell street 1 Turnbull road aa a public way. A Florida, and will »pcnd the wln^r can Ix'glon auxlliarj’ will, meet'to familiar "another prednet report-1 Caropbell'a Roosevelt /W inner Mrs. Henry Madden, chairman, revised map of Woodland Park at New Smyrna Beach. morrow evening at ' ing School Hours. ____ i^avid Thomas, 16 Courlland and her committee in charge of the tract waa accepted. -

Extensions of Remarks E840 HON. JODY B. HICE HON. JIM JORDAN

E840 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks June 16, 2017 of diversity that makes it one of the most dy- ther, the late former Congressman Clarence J. world peace is achievable through public serv- namic and vibrant cities in America. Brown, Sr., represented Ohio’s Seventh Con- ice. America is a land of opportunity for those gressional District in the House from 1939 to Throughout her career President Sirleaf has who are willing to work hard and abide by the 1965. A Navy veteran of World War II and the never been afraid to stand up and speak out laws. Korean War, Bud was a 1947 graduate of for what she believed was best for Liberians. We must assure that DACA beneficiaries Duke University and a 1949 graduate of Har- Her career in public service began in 1972 as continue to enjoy the opportunity to pursue vard Business School. an assistant minister of finance under Presi- their American dreams. Bud succeeded his father in Congress in dent William Tolbert. She was forced to flee We are a better country for doing so. 1965, representing the people of the Seventh Liberia in 1980 after publicly speaking out f District with distinction until 1983. Following against the government of Samuel Doe. She his House service, he was tapped by Presi- returned to Liberia in 1985 to seek public of- HITACHI AUTOMOTIVE SYSTEMS dent Reagan to serve as the nation’s fifth fice only to be sentenced to ten years in pris- AMERICAS 20TH ANNIVERSARY Deputy Secretary of Commerce. He ably filled on for her comments criticizing the govern- the role of Acting Secretary for several months ment. -

This Year's Presidential Prop8id! CONTENTS

It's What's Inside That Counts RIPON MARCH, 1973 Vol. IX No.5 ONE DOLLAR This Year's Presidential Prop8ID! CONTENTS Politics: People .. 18 Commentary Duly Noted: Politics ... 25 Free Speech and the Pentagon ... .. .. 4 Duly Noted: Books ................ ......... 28 Editorial Board Member James. Manahan :e Six Presidents, Too Many Wars; God Save This views the past wisdom of Sen. RIchard M .. NIX Honorable Court: The Supreme Court Crisis; on as it affects the cases of A. Ernest FItzge The Creative Interface: Private Enterprise and rald and Gordon Ru1e, both of whom are fired the Urban Crisis; The Running of Richard Nix Pentagon employees. on; So Help Me God; The Police and The Com munity; Men Behind Bars; Do the Poor Want to Work? A Social Psychological Study of The Case for Libertarianism 6 Work Orientations; and The Bosses. Mark Frazier contributing editor of Reason magazine and New England coordinator for the Libertarian Party, explains why libe:allsm .and Letters conservatism are passe and why libertanan 30 ism is where it is at. 14a Eliot Street 31 Getting College Republicans Out of the Closet 8 Last month, the FORUM printed the first in a series of articles about what the GOP shou1d be doing to broaden its base. Former RNC staff- er J. Brian Smith criticized the Young Voters Book Review for the President for ignoring college students. YVP national college director George Gordon has a few comments about what YVP did on The Politics of Principle ................ 22 campus and what the GOP ought to be doing John McCIaughry, the one-time obscure Ver in the future. -

Political Parties, Interest Groups, and Elections in Ohio

Chapter 8 Political Parties, Interest Groups, and Elections in Ohio Major and Minor Parties in Ohio Ohio has a very rich history of strong political parties. The Ohio Democratic Party is older than the Republican Party, having its origins in the foundingdistribute period of the state. Initially, a party known as the Federalists served as the main rival to the Dem- ocratic Party (or the Democratic or Jeffersonian Republicans,or as they were sometimes know). As the Federalist Party faded, the Whig Party emerged as the opponent of the Democrats.1 The Whigs were strong in the “Western Reserve” part of the state, which is the northeast corner of Ohio. The Whig Party held to strong abolitionist views and so served as the natural core for the emergence of Republican Party in Ohio in the 1850s. post, Beyond the Democrats and the Republicans, minor political parties have struggled to gain ballot access and sustain their legal status in Ohio. In the 2012 general election, no minor parties received even 1 percent of the vote, although the Libertarian Party presidential candidate came close, receiving .89 percent of the popular vote. Among thecopy, other minor parties, the Socialist Party presidential can- didate received .05 percent of the vote, while the Constitution Party received .15 percent and the Green Party received .33 percent. Even thoughnot third parties do not currently have much hope for winning the plurality of the vote necessary to actually be awarded an office in Ohio, they can affect a close election by siphoning off votes that might otherwise go to one of the majorDo party candidates. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ---X in Re

Case 8-10-73295-reg Doc 1214 Filed 04/29/13 Entered 04/29/13 15:56:41 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------X In re: Chapter 11 THE BROWN PUBLISHING COMPANY, DAN’S PAPERS, INC., BROWN MEDIA HOLDINGS Case No. 10-73295 COMPANY, BOULDER BUSINESS INFORMATION INC., BROWN BUSINESS LEDGER, LLC, (Jointly Administered) BROWN PUBLISHING INC., LLC, BUSINESS PUBLICATIONS, LLC, THE DELAWARE GAZETTE COMPANY, SC BIZ NEWS, LLC, TEXAS COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERS, INC., TEXAS BUSINESS NEWS, LLC, TROY DAILY NEWS, INC., UPSTATE BUSINESS NEWS, LLC, UTAH BUSINESS PUBLISHERS, LLC, ARG, LLC, Debtors. ------------------------------------------------------X MEMORANDUM DECISION Appearances: McBreen & Kopko Attorneys for Movant Roy E. Brown 500 North Broadway, Suite 129 Jericho, New York 11753 By: Kenneth A. Reynolds, Esq.; Evan Gewirtz, Esq. K&L Gates Attorneys for The Brown Publishing Company Liquidating trust 599 Lexington Avenue New York, NY 10022 By: Edward M. Fox, Esq.; Eric T. Moser, Esq. Honorable Dorothy T. Eisenberg, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Case 8-10-73295-reg Doc 1214 Filed 04/29/13 Entered 04/29/13 15:56:41 Introduction On June 16, 2011, pursuant to the plan of liquidation in this case, a liquidating trust was established in order to succeed to all assets and causes of action of the bankruptcy estates of the above-captioned debtors. The liquidating trust has commenced adversary proceedings against certain former officers, directors, shareholders, and affiliates of the debtors, by and through its special counsel, the law firm of K&L Gates (―KLG‖). KLG had been counsel to the debtors-in- possession during the course of these Chapter 11 cases.