ICZN, Homonymy, Synonymy and Law of Priority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

I Scope and Importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker System & Cronquist

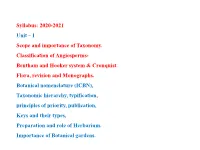

Syllabus: 2020-2021 Unit – I Scope and importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker system & Cronquist. Flora, revision and Monographs. Botanical nomenclature (ICBN), Taxonomic hierarchy, typification, principles of priority, publication, Keys and their types, Preparation and role of Herbarium. Importance of Botanical gardens. PLANT KINGDOM Amongst plants nearly 15,000 species belong to Mosses and Liverworts, 12,700 Ferns and their allies, 1,079 Gymnosperms and 295,383 Angiosperms (belonging to about 485 families and 13,372 genera), considered to be the most recent and vigorous group of plants that have occurred on earth. Angiosperms occupy the majority of the terrestrial space on earth, and are the major components of the world‘s vegetation. Brazil (First) and Colombia (second), both located in the tropics considered to be countries with the most diverse angiosperms floras China (Third) even though the main part of her land is not located in the tropics, the number of angiosperms still occupies the third place in the world. In INDIA there are about 18042 species of flowering plants approximately 320 families, 40 genera and 30,000 species. IUCN Red list Categories: EX –Extinct; EW- Extinct in the Wild-Threatened; CR -Critically Endangered; VU- Vulnerable Angiosperm (Flowering Plants) SPECIES RICHNESS AROUND THE WORLD PLANT CLASSIFICATION Historia Plantarum - the earliest surviving treatise on plants in which Theophrastus listed the names of over 500 plant species. Artificial system of Classification Theophrastus attempted common groupings of folklore combined with growth form such as ( Tree Shrub; Undershrub); or Herb. Or (Annual and Biennials plants) or (Cyme and Raceme inflorescences) or (Archichlamydeae and Meta chlamydeae) or (Upper or Lower ovarian ). -

Review and Updated Checklist of Freshwater Fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, Distribution and Conservation Status

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (March 2017), 4(Suppl. 1): 1–114 Received: October 18, 2016 © 2017 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: February 30, 2017 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.7508/iji.2017 http://www.ijichthyol.org Review and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, distribution and conservation status Hamid Reza ESMAEILI1*, Hamidreza MEHRABAN1, Keivan ABBASI2, Yazdan KEIVANY3, Brian W. COAD4 1Ichthyology and Molecular Systematics Research Laboratory, Zoology Section, Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran 2Inland Waters Aquaculture Research Center. Iranian Fisheries Sciences Research Institute. Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, Bandar Anzali, Iran 3Department of Natural Resources (Fisheries Division), Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan 84156-83111, Iran 4Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 6P4 Canada *Email: [email protected] Abstract: This checklist aims to reviews and summarize the results of the systematic and zoogeographical research on the Iranian inland ichthyofauna that has been carried out for more than 200 years. Since the work of J.J. Heckel (1846-1849), the number of valid species has increased significantly and the systematic status of many of the species has changed, and reorganization and updating of the published information has become essential. Here we take the opportunity to provide a new and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran based on literature and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history and new fish collections. This article lists 288 species in 107 genera, 28 families, 22 orders and 3 classes reported from different Iranian basins. However, presence of 23 reported species in Iranian waters needs confirmation by specimens. -

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature INTERNATIONAL CODE OF ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE Fourth Edition adopted by the International Union of Biological Sciences The provisions of this Code supersede those of the previous editions with effect from 1 January 2000 ISBN 0 85301 006 4 The author of this Code is the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature Editorial Committee W.D.L. Ride, Chairman H.G. Cogger C. Dupuis O. Kraus A. Minelli F. C. Thompson P.K. Tubbs All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the publisher and copyright holder. Published by The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 c/o The Natural History Museum - Cromwell Road - London SW7 5BD - UK © International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 Explanatory Note This Code has been adopted by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and has been ratified by the Executive Committee of the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS) acting on behalf of the Union's General Assembly. The Commission may authorize official texts in any language, and all such texts are equivalent in force and meaning (Article 87). The Code proper comprises the Preamble, 90 Articles (grouped in 18 Chapters) and the Glossary. Each Article consists of one or more mandatory provisions, which are sometimes accompanied by Recommendations and/or illustrative Examples. In interpreting the Code the meaning of a word or expression is to be taken as that given in the Glossary (see Article 89). -

First Report of Ancylostoma Ceylanicum in Wild Canids Q ⇑ Felicity A

International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife 2 (2013) 173–177 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijppaw Brief Report First report of Ancylostoma ceylanicum in wild canids q ⇑ Felicity A. Smout a, R.C. Andrew Thompson b, Lee F. Skerratt a, a School of Public Health, Tropical Medicine and Rehabilitation Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland 4811, Australia b School of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia 6150, Australia article info abstract Article history: The parasitic nematode Ancylostoma ceylanicum is common in dogs, cats and humans throughout Asia, Received 19 February 2013 inhabiting the small intestine and possibly leading to iron-deficient anaemia in those infected. It has pre- Revised 23 April 2013 viously been discovered in domestic dogs in Australia and this is the first report of A. ceylanicum in wild Accepted 26 April 2013 canids. Wild dogs (dingoes and dingo hybrids) killed in council control operations (n = 26) and wild dog scats (n = 89) were collected from the Wet Tropics region around Cairns, Far North Queensland. All of the carcasses (100%) were infected with Ancylostoma caninum and three (11.5%) had dual infections with A. Keywords: ceylanicum. Scats, positively sequenced for hookworm, contained A. ceylanicum, A. caninum and Ancylos- Ancylostoma ceylanicum toma braziliense, with A. ceylanicum the dominant species in Mount Windsor National Park, with a prev- Dingo Canine alence of 100%, but decreasing to 68% and 30.8% in scats collected from northern and southern rural Hookworm suburbs of Cairns, respectively. -

Invasive Fruit Flies (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Meet in a Biodiversity Hotspot

J. Entomol. Res. Soc., 19(1): 61-69, 2017 ISSN:1302-0250 Invasive Fruit Flies (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Meet in a Biodiversity Hotspot Carla REGO1* António Franquinho AGUIAR2 Délia CRAVO2 Mário BOIEIRO1 1Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes (cE3c), Azorean Biodiversity Group and Department of Agrarian Sciences, University of Azores, Angra do Heroísmo, Azores, PORTUGAL 2Laboratório de Qualidade Agrícola, Camacha, Madeira, PORTUGAL e-mails: *[email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Oceanic islands’ natural ecosystems worldwide are severely threatened by invasive species. Here we discuss the recent finding of three exotic drosophilids in Madeira archipelago -Acletoxenus formosus (Loew, 1864), Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura, 1931) and Zaprionus indianus (Gupta, 1970). Drosophila suzukii and Z. indianus are invasive species responsible for severe economic losses in fruit production worldwide and became the dominant drosophilids in several invaded areas menacing native species. We found that these exotic species are relatively widespread in Madeira but, at present, seem to be restricted to human disturbed environments. Finally, we stress the need to define a monitoring program in the short-term to determine population spread and environmental damages inflicted by the two invasive drosophilids, in order to implement a sustainable and effective control management strategy. Key words: Biological invasions, Drosophila suzukii, invasive species, island biodiversity, Madeira archipelago, Zaprionus indianus. INTRODUCTION Oceanic islands are known to contribute disproportionately to their area for Global biodiversity and by harbouring unique evolutionary lineages and emblematic plants and animals (Grant,1998; Whittaker and Fernández-Palácios, 2007). Nevertheless, many of these organisms are particularly vulnerable to human-mediated changes in their habitats due to their narrow range size, low abundance and habitat specificity (Paulay, 1994). -

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra Serpentina

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra serpentina Rylen Nakama FISH 423: Olden 12/5/14 Figure 1. The Common Snapping Turtle, one of the most widespread reptiles in North America. Photo taken in Quebec, Canada. Image from https://www.flickr.com/photos/yorthopia/7626614760/. Classification Order: Testudines Family: Chelydridae Genus: Chelydra Species: serpentina (Linnaeus, 1758) Previous research on Chelydra serpentina (Phillips et al., 1996) acknowledged four subspecies, C. s. serpentina (Northern U.S. and Figure 2. Side profile of Chelydra serpentina. Note Canada), C. s. osceola (Southeastern U.S.), C. s. the serrated posterior end of the carapace and the rossignonii (Central America), and C. s. tail’s raised central ridge. Photo from http://pelotes.jea.com/AnimalFact/Reptile/snapturt.ht acutirostris (South America). Recent IUCN m. reclassification of chelonians based on genetic analyses (Rhodin et al., 2010) elevated C. s. rossignonii and C. s. acutirostris to species level and established C. s. osceola as a synonym for C. s. serpentina, thus eliminating subspecies within C. serpentina. Antiquated distinctions between the two formerly recognized North American subspecies were based on negligible morphometric variations between the two populations. Interbreeding in the overlapping range of the two populations was well documented, further discrediting the validity of the subspecies distinction (Feuer, 1971; Aresco and Gunzburger, 2007). Therefore, any emphasis of subspecies differentiation in the ensuing literature should be disregarded. Figure 3. Front-view of a captured Chelydra Continued usage of invalid subspecies names is serpentina. Different skin textures and the distinctive pink mouth are visible from this angle. Photo from still prevalent in the exotic pet trade for C. -

Tracing History

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911 Tracing History Phylogenetic, Taxonomic, and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family BY ANNIKA VINNERSTEN ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2003 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lindahlsalen, EBC, Uppsala, Friday, December 12, 2003 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Vinnersten, A. 2003. Tracing History. Phylogenetic, Taxonomic and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911. 33 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-5814-9 This thesis concerns the history and the intrafamilial delimitations of the plant family Colchicaceae. A phylogeny of 73 taxa representing all genera of Colchicaceae, except the monotypic Kuntheria, is presented. The molecular analysis based on three plastid regions—the rps16 intron, the atpB- rbcL intergenic spacer, and the trnL-F region—reveal the intrafamilial classification to be in need of revision. The two tribes Iphigenieae and Uvularieae are demonstrated to be paraphyletic. The well-known genus Colchicum is shown to be nested within Androcymbium, Onixotis constitutes a grade between Neodregea and Wurmbea, and Gloriosa is intermixed with species of Littonia. Two new tribes are described, Burchardieae and Tripladenieae, and the two tribes Colchiceae and Uvularieae are emended, leaving four tribes in the family. At generic level new combinations are made in Wurmbea and Gloriosa in order to render them monophyletic. The genus Androcymbium is paraphyletic in relation to Colchicum and the latter genus is therefore expanded. -

Conspecific Pollen on Insects Visiting Female Flowers of Phoradendron Juniperinum (Viscaceae) in Western Arizona

Western North American Naturalist Volume 77 Number 4 Article 7 1-16-2017 Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona William D. Wiesenborn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Wiesenborn, William D. (2017) "Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 77 : No. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol77/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 77(4), © 2017, pp. 478–486 CONSPECIFIC POLLEN ON INSECTS VISITING FEMALE FLOWERS OF PHORADENDRON JUNIPERINUM (VISCACEAE) IN WESTERN ARIZONA William D. Wiesenborn1 ABSTRACT.—Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) is a dioecious, parasitic plant of juniper trees ( Juniperus [Cupressaceae]) that occurs from eastern California to New Mexico and into northern Mexico. The species produces minute, spherical flowers during early summer. Dioecious flowering requires pollinating insects to carry pollen from male to female plants. I investigated the pollination of P. juniperinum parasitizing Juniperus osteosperma trees in the Cerbat Mountains in western Arizona during June–July 2016. I examined pollen from male flowers, aspirated insects from female flowers, counted conspecific pollen grains on insects, and estimated floral constancy from proportions of conspecific pollen in pollen loads. -

International Code of Zoological Nomenclature Adopted by the XV

fetsS WW w»È¥STOPiifliîM «SSII »c»»W»tAaVŒHiWJ ^®{f,!s,)'ffi!îS kîvî*X-v!»J#Ï*>%!•»» Hmtljil «jiRfij mrmu :»;!N\>VS'. W]'■;;} ''.;'-'l|]■■ iï:'ï;llI vl'-'iv;-' H Sifcfe-•*: v:v:;::vv;:';:vv V>|lV.\VO.kvS'vk\ \>y.js. ini&K3«MM©ifnfi* >sv îv.vtvîlPi?>^\sîv-\s\Kv;>^v#i'S®S?:1V:is ';v':::SS!'S 'V.\'\kiv :';$llffe$ fW'É vwln/fr^&V- Sj|;«Siî:8KKîvfihffWtf Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the publisher and copyright holder. Published by The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 c/o The Natural History Museum - Cromwell Road - London SW7 5BD - UK © International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999 Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature INTERNATIONAL CODE OF ZOOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE Fourth Edition adopted by the International Union ofBiological Sciences The provisions of this Code supersede those of the previous editions with effect from 1 January 2000 'ICZ^Cj ISBN 0 85301 006 4 Original from and digitized by National University of Singapore Libraries The author of this Code is the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature Editorial Committee W.D.L. -

Evolution of a Pest: Towards the Complete Neuroethology of Drosophila Suzukii and the Subgenus Sophophora Ian W

bioRxiv preprint first posted online Jul. 28, 2019; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/717322. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not peer-reviewed) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. ARTICLES PREPRINT Evolution of a pest: towards the complete neuroethology of Drosophila suzukii and the subgenus Sophophora Ian W. Keesey1*, Jin Zhang1, Ana Depetris-Chauvin1, George F. Obiero2, Markus Knaden1‡*, and Bill S. Hansson1‡* Comparative analysis of multiple genomes has been used extensively to examine the evolution of chemosensory receptors across the genus Drosophila. However, few studies have delved into functional characteristics, as most have relied exclusively on genomic data alone, especially for non-model species. In order to increase our understanding of olfactory evolution, we have generated a comprehensive assessment of the olfactory functions associated with the antenna and palps for Drosophila suzukii as well as sev- eral other members of the subgenus Sophophora, thus creating a functional olfactory landscape across a total of 20 species. Here we identify and describe several common elements of evolution, including consistent changes in ligand spectra as well as relative receptor abundance, which appear heavily correlated with the known phylogeny. We also combine our functional ligand data with protein orthologue alignments to provide a high-throughput evolutionary assessment and predictive model, where we begin to examine the underlying mechanisms of evolutionary changes utilizing both genetics and odorant binding affinities. In addition, we document that only a few receptors frequently vary between species, and we evaluate the justifications for evolution to reoccur repeatedly within only this small subset of available olfactory sensory neurons. -

Johnson Stander 2020

Gene Regulatory Network Homoplasy Underlies Recurrent Sexually Dimorphic Fruit Fly Pigmentation Jesse Hughes, Rachel Johnson, and Thomas M. Williams The Department of Biology at the University of Dayton; 300 College Park, Dayton, OH 45469 ABSTRACT Widespread Dimorphism in Sophophora and Beyond Pigment Metabolic Pathway Utilization in H. duncani Species with dimorphic tergite pigmentation are Traits that appear discontinuously along phylogenies may be explained by independent ori- widespread throughout the Drosophila genus. (A-E) Female and (A’-E’) male expressions of H. duncani gins (homoplasy) or repeated loss (homology). While discriminating between these models Sophophora subgenus species groups and species pigment metabolic pathway genes, and (F and F’) cartoon is difficult, the dissection of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) which drive the development are indicated by the gray background. D. busckii and representation of the pigmentation phenotype. (G) of such repeatedly occurring traits can offer a mechanistic window on this fundamental Summary of the H. duncani pathway use includes robust D. funebris are included as non-Sophophora species problem. The GRN responsible for the male-specific pattern of Drosophila (D.) melano- expression of all genes, with dimorphic expressions of Ddc, from the Drosophila genus that respectively exhibit gaster melanic tergite pigmentation has received considerable attention. In this system, a ebony, tan, and yellow. (A, A’) pale, (B, B’) Ddc, (C, C’) monomorphic and dimorphic patterns of tergite metabolic pathway of pigmentation enzyme genes is expressed in spatial and sex-specific ebony, (D, D’) tan, and (E, E’) yellow. Red arrowheads pigmentation. The homologous A5 and A6 segment (i.e., dimorphic) patterns. The dimorphic expression of several genes is regulated by the indicate robust patterns of dimorphic expression in the tergites are indicated for each species, the segments Bab transcription factors, which suppress pigmentation enzyme expression in females, by dorsal abdominal epidermis.