Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Critics Association of North America Bestows Its Inaugural Award for Best New Opera to Breaking the Waves

The Music Critics Association of North America bestows its inaugural Award for Best New Opera to Breaking the Waves The winner was chosen by an Awards Committee co-chaired by Heidi Waleson and George Loomis, and including Alex Ross, John Rockwell and Arthur Kaptainis Both composer Missy Mazzoli and librettist Royce Vavrek will be honored at the award presentation ceremony, to take place on July 19 during the MCANA Annual Meeting in Santa Fe June 20, 2017 - FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE - The Music Critics Association of North America (MCANA) is pleased to announce that its inaugural Award for Best New Opera has been given to composer Missy Mazzoli and librettist Royce Vavrek for Breaking the Waves, which received its premiere on September 22, 2016 by Opera Philadelphia in conjunction with Beth Morrison Projects. The award was created to honor musical and theatrical excellence in a fully-staged opera that received its world premiere in North America during the preceding calendar year. The Award will be presented to the winners on July 19 during the opening of the MCANA Annual Meeting in Santa Fe, NM. Mazzoli and Vavrek will be also be profiled in MCANA’s web publication Classical Voice North America. The other finalists were Fellow Travelers, by composer Gregory Spears and librettist Greg Pierce, and Anatomy Theater by composer David Lang and librettist Mark Dion. After soliciting nominations from MCANA members, the finalists were chosen by an Awards Committee co-chaired by MCANA members Heidi Waleson, opera critic of The Wall Street Journal, and George Loomis, longtime contributor to the Financial Times and Musical America, alongside committee members Arthur Kaptainis, who writes for the Montreal Gazette and Musical Toronto, representing Canada; John Rockwell, former critic and arts editor of The New York Times and co-New York correspondent of Opera (UK); and Alex Ross, music critic of The New Yorker. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

School of Music 2016–2017

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Music 2016–2017 School of Music 2016–2017 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 112 Number 7 July 25, 2016 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Goff-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

September 2001 Information for Subscribers

21ST CENTURY MUSIC SEPTEMBER 2001 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $84.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $36.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $10.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2001 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Typescripts should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors with access to IBM compatible word-processing systems are encouraged to submit a floppy disk, or e-mail, in addition to hard copy. -

From the Artistic Director

From the Artistic Director John Cage was a great American In his composer and deserves centenary to be celebrated for his year, we have enormous contributions considered to the music of the 20th Cage as a century and beyond. Buddhist, That’s obvious, right? After all, thousands of a painter, concerts all over the world will have been devoted poet, and to celebrating this year’s Cage Centennial this philosopher. year. (He was born on September 5, 1912.) Yet in This weekend, those thousands of events we have seen relatively we focus on little attention played to John Cage, Composer. John Cage, We have seen multiple essays and a new book composer. describing Cage’s relationship to Zen Buddhism. We have seen exhibitions of his paintings, his poetry, his correspondence. We have focused on Cage’s personal relationship with Merce Cunningham and his aesthetic rapport with Rauschenberg and Duchamp. We have fêted his well-known interest in Thoreau, in Joyce and Satie. We have saluted the cross- cultural, and even countercultural impulses behind his devotion to chance procedures and the I Ching. A well-known composer, and good friend of mine, claims that Cage was a revolutionary theorist, “but not really a composer” – a view shared by Cage’s most famous teacher, Arnold Schoenberg, who while bemoaning Cage’s utter lack of sensitivity to harmony nevertheless proclaimed him to be, “an inventor of great genius.” Judging from the welcome outpouring of affection and attention this year’s centennial celebrations have presented, Cage is apparently “all of the above.” But is he a real composer? Our answer is, resoundingly, YES! He was a great composer, and furthermore, his music can stand alone as great music with SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS 1 2012-13 SEASON or without the attractive aspects of his personal philosophy and So in his percussion music Cage could specify an artistic taste. -

Jasper String Quartet

Jasper String Quartet CONTACT Jasper String Quartet 205 Forrest Ave Elkins Park, PA 19027 PHONE (314) 607-2042 email | website Biography QUOTES Winner of the prestigious CMA Cleveland Quartet Award, Philadelphia's Jasper String Quartet is the “The [Jasper String Quartet] Professional Quartet in Residence at Temple University's Center for Gifted Young Musicians. displayed joie de vivre and The Jaspers have been hailed as “sonically delightful and expressively compelling” (The Strad) and athleticism - and perhaps most "powerful" (New York Times). "The Jaspers... match their sounds perfectly, as if each swelling chord were tellingly, grins all around.” coming out of a single, impossibly well-tuned organ, instead of four distinct instruments." (New Haven Advocate) – The Strad The quartet records exclusively for Sono Luminus and have released three highly acclaimed albums - Beethoven Op. 131, The Kernis Project: Schubert, and The Kernis Project: Beethoven. “The Jasper Quartet generates an electricity that seems to Current Projects crackle through the crowd.” The Quartet rounds out their commission tour of Aaron Jay Kernis’ 3rd String Quartet "River" in 2016-17 with performances at Wigmore Hall and at Classic Chamber Concerts in Florida. The – Naples Daily News Quartet's Carnegie Hall Recital of the work last season received a glowing review in The Strad. “The music breathed and The Quartet will release their latest album with Sono Luminus in early 2017 featuring quartets by Donnacha Dennehy, Annie Gosfield, Judd Greenstein, Ted Hearne, David Lang, Missy Mazzoli, and swelled in an expressive way Caroline Shaw. without being over-calculated. In addition, this season they will launch their inaugural season of Jasper Chamber Concerts, a series in Even the moments of silence Philadelphia devoted to world class performances of masterworks from around the world and vibrated with an energy.” Philadelphia. -

Victoire Welcome to VIVA! & Gala Friday, February 22, 2013 • 7:30 P.M

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� �������������������� ����� �������� �������� Victoire Welcome to VIVA! & Gala Friday, February 22, 2013 • 7:30 p.m. The new season of concerts at the Cleveland Museum of Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Art showcases 16 outstanding performances from around the globe and the U.S. Among the many highlights of ENSEMBLE the season are programs that tie into exhibitions, the openings of the Renaissance and Islamic galleries, and Missy Mazzoli (compositions, keyboards) the stunningly beautiful Ames Family Atrium. Mellissa Hughes (voice) Olivia De Prato (violin) Tonight please join me in welcoming -

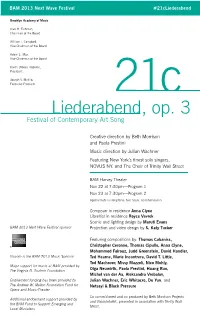

21C Liederabend , Op 3

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #21cLiederabend Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer 21c Liederabend, op. 3 Festival of Contemporary Art Song Creative direction by Beth Morrison and Paola Prestini Music direction by Julian Wachner Featuring New York’s finest solo singers, NOVUS NY, and The Choir of Trinity Wall Street BAM Harvey Theater Nov 22 at 7:30pm—Program 1 Nov 23 at 7:30pm—Program 2 Approximate running time: two hours, no intermission Composer in residence Anna Clyne Librettist in residence Royce Vavrek Scenic and lighting design by Maruti Evans BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Projection and video design by S. Katy Tucker Featuring compositions by: Thomas Cabaniss, Christopher Ceronne, Thomas Cipullo, Anna Clyne, Mohammed Fairouz, Judd Greenstein, David Handler, Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Ted Hearne, Marie Incontrera, David T. Little, Tod Machover, Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Major support for music at BAM provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Olga Neuwirth, Paola Prestini, Huang Ruo, Michel van der Aa, Aleksandra Vrebalov, Endowment funding has been provided by Julian Wachner, Eric Whitacre, Du Yun, and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Netsayi & Black Pressure Opera and Music-Theater Co-commisioned and co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects Additional endowment support provided by and VisionIntoArt, presented in association with Trinity Wall the BAM Fund to Support Emerging and Street. Local Musicians 21c Liederabend Op. 3 Being educated in a classical conservatory, the Liederabend (literally “Song Night” and pronounced “leader-ah-bent”) was a major part of our vocal educations. -

Y | Opera | Studies Today Developing New Opera in the Age of #Metoo

Y | Opera | Studies Today Developing New Opera in the Age of #MeToo A Zoom Conference May 8, 2020 Yale Department of Music May 6 – 7 VIdeo streaMIng of prism (ellen reId and roxIe perkIns, 2018) A link will be emailed to registered participants of the conference. Music Ellen Reid Libretto Roxie Perkins Director James Darrah Conductor Julian Wachner Producer Beth Morrison Projects Featuring Rebecca Jo Loeb, Anna Schubert, noVus ny, and The Choir of Trinity Wall Street Sound design Garth MacAleavey Choreographer and assistant director Chris Emile Set design Adam Rigg Costume design Molly Irelan Lighting design Pablo Santiago-Brandwein May 8 10 a.m. WelcoMe and IntroductIon Gundula Kreuzer lIghtnIng talks and dIscussIon I: neW opera and gender Wayne Heisler Jr. “Bigger than Germont; Or, the Operatic Canon as Codependency” Jane Forner “Opera as Activism and Social Critique: The Works of Cecilie Ore, 2008 – 2019” Lucy Caplan “‘A Little Woman with a Big Thought’: Gender and Labor in a New Production of Shirley Graham’s Tom-Tom” Chair and Respondent: Ryan Minor 11:15 Short break 11:30 lIghtnIng talks and dIscussIon II: opera and/as experIMent Joy Calico “Engaging Experimental Opera: Chaya Czernowin’s Infinite Now (2017)” W. Anthony Sheppard “Shara Nova’s You Us We All and #MeToo” Chair and Respondent: Alessandra Campana poster presentatIon “Ms., Opera, Music, Mr.: A Rhetorical Analysis of Contemporary Classical Music Criticism” Allison Chu and Frances Pollock Chair and Respondent: Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg 1 p.m. lunch break 2:00 conVersatIon: -

May 23–June 11, 2016

FOR RELEASE: March 8, 2016 PROGRAM UPDATES AND Contact: Katherine E. Johnson NEW EVENTS ADDED (212) 875-5718; [email protected] UPDATED May 25, 2016 May 23–June 11, 2016 THREE-WEEK EXPLORATION OF TODAY’S MUSIC PRESENTED BY THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC AND TWELVE PARTNERS IN EIGHT VENUES THROUGHOUT NEW YORK CITY NEWLY ADDED: Insights Series: Free NY PHIL BIENNIAL Preview Night with Alan Gilbert, May 11 at David Rubenstein Atrium NY PHIL BIENNIAL Play Dates: Post-Concert Meet-Ups with Composers and Artists #biennialist Social Media Contest Programs for New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival with Works by More Than 30 Composers June 5–7, 2016, at National Sawdust BOULEZ’s Messagesquisse and STUCKY’s Second Concerto for Orchestra Added to Finale Program with Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic In Tribute to the Late Composers June 11 at David Geffen Hall From May 23 to June 11, 2016, the New York Philharmonic and Music Director Alan Gilbert will present the second NY PHIL BIENNIAL, a wide-ranging exploration of today’s music by an array of contemporary and modern composers. A flagship project of the New York Philharmonic, the NY PHIL BIENNIAL brings together an international roster of composers, performers, and curatorial voices for concerts presented both on the Lincoln Center campus and in venues throughout the city. The 2016 NY PHIL BIENNIAL will feature works by more than 100 composers, more than half of whom are American, spanning in age and experience from students to iconic legends. Reflecting the Philharmonic’s growing collaborations with music education organizations from New York City to Asia, in the second NY PHIL BIENNIAL the Philharmonic will present new-music programs from some of the country’s top music schools, ranging from high school to university levels, and youth choruses from the East and West Coasts. -

Juilliard Orchestra Karina Canellakis, Conductor

Saturday Evening, September 21, 2019, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Karina Canellakis, Conductor MISSY MAZZOLI (b. 1980) Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres) LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 19 Allegro con brio Adagio Rondo: Molto allegro Intermission RICHARD STRAUSS (1864–1949) Ein Heldenleben (A Hero’s Life), Op. 40 The Hero The Hero’s Adversaries The Hero’s Companion The Hero’s Deeds of War The Hero’s Works of Peace The Hero’s Retirement Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including an intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. and gently out-of-tune guitars, and I draw on Notes on the Program inspirations as diverse as Baroque music, by James M. Keller noise, and modern electronica.” Much of that description characterizes Sinfonia (for Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres) Orbiting Spheres), written in 2013 for cham- MISSY MAZZOLI ber orchestra and revised in 2016 for full Born October 27, 1980, in Lansdale, symphony orchestra. She described it as Pennsylvania “music in the shape of a solar system, a collection of rococo loops that twist around An esteemed and productive presence in each other within a larger orbit.” New York City’s new-music scene, Missy Mazzoli has written works in many genres, “The word ‘sinfonia’ refers to baroque from chamber music to symphonic scores works for chamber orchestra,” Mazzoli to operas. -

Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century

A SCENE WITHOUT A NAME: INDIE CLASSICAL AND AMERICAN NEW MUSIC IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY William Robin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Mark Katz Andrea Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Benjamin Piekut © 2016 William Robin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT WILLIAM ROBIN: A Scene Without a Name: Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century (Under the direction of Mark Katz) This dissertation represents the first study of indie classical, a significant subset of new music in the twenty-first century United States. The definition of “indie classical” has been a point of controversy among musicians: I thus examine the phrase in its multiplicity, providing a framework to understand its many meanings and practices. Indie classical offers a lens through which to study the social: the web of relations through which new music is structured, comprised in a heterogeneous array of actors, from composers and performers to journalists and publicists to blog posts and music venues. This study reveals the mechanisms through which a musical movement establishes itself in American cultural life; demonstrates how intermediaries such as performers, administrators, critics, and publicists fundamentally shape artistic discourses; and offers a model for analyzing institutional identity and understanding the essential role of institutions in new music. Three chapters each consider indie classical through a different set of practices: as a young generation of musicians that constructed itself in shared institutional backgrounds and performative acts of grouping; as an identity for New Amsterdam Records that powerfully shaped the record label’s music and its dissemination; and as a collaboration between the ensemble yMusic and Duke University that sheds light on the twenty-first century status of the new-music ensemble and the composition PhD program.