Introduction Going to War: Europe and the Wider World, 1914- 1915

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wwi 1914 - 1918

ABSTRACT This booklet will introduce you to the key events before and during the First World War. Taking place from 1914 – 1918, millions of people across the world lost their lives in what was supposed to be ‘the war to end all wars’. Fighting on this scale had never been seen before. The work in this booklet will help you understand why such a horrific conflict begun. Ms Marsh WWI 1914 - 1918 Year 8 History Why did the First World War begin? L.O: I can explain the causes of the First World War. 1. In what year did the war begin? 2. In what year did the war end? 3. How many years did it last? (Do now answers at end of booklet) The First World War begun in August 1914. It took the world by surprise, and seemed to happen overnight. In reality, tension between countries in Europe had been increasing for some years before. The final event that triggered war, the assassination of a young heir to the Austria – Hungary throne, demonstrates how this tension had been building. Europe in the early 20th century was a place where newly formed countries such as Italy started to challenge the dominance of countries with empires. An empire is when one country rules over others around the world. Some countries began to demand their independence and did not want to be ruled by an empire. The map opposite shows just how vast the empires of Europe were; Britain had control of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, East and South Africa and India. -

Timeline of Start Of

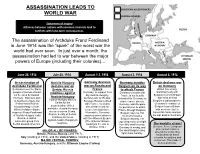

ASSASSINATION LEADS TO EUROPEAN ALLIED POWERS WORLD WAR CENTRAL POWERS Statement of Inquiry Alliances between nations with common interests lead to conflicts with long-term consequences. RUSSIA GERMANY GERMANY The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand FRANCE AUSTRIA- in June 1914 was the “spark” of the worst war the HUNGARY world had ever seen. In just over a month, the Bosnia assassination had led to war between the major OTTOMAN EMPIRE powers of Europe (including their colonies)… June 28, 1914 July 28, 1914 August 1-3, 1914 August 3, 1914 August 4, 1914 Assassination of Austria-Hungary Germany declares Germany invades Britain declares war Archduke Ferdinand declares war on war on Russia and Belgium on its way on Germany Serbia believes the Slavic Serbia; Russia France to attack France Britain has a long- people of Europe should mobilizes against Germany, to support their Germany’s border with standing treaty with Belgium in which Britain not be ruled by Austria- Austria-Hungary ally Austria-Hungary, France is too heavily Hungary. Bosnia is part declares war on Russia. defended for Germany to agreed to defend Austria-Hungary blames of Austria-Hungary, but Because Russia is allied attack France directly. Belgium’s independence. Serbia for the Serbia thinks Bosnia with France, Germany Germany asks Belgium Germany’s invasion of assassination of their should belong to them. also declares war on for permission to attack Belgium leaves Britain archduke. Austria-Hungary When Archduke (future France two days later. France through Belgium. with no choice but to declares war on Serbia. emperor) Franz-Ferdinand Meanwhile, Germany Belgium says no, but honor this treaty and join Russia, an ally of Serbia, of Austria-Hungary visits makes a secret alliance Germany invades the war against Germany. -

Perceptionsjournal of International Affairs

PERCEPTIONSJOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS PERCEPTIONS Summer-Autumn 2015 Volume XX Number 2-3 XX Number 2015 Volume Summer-Autumn PERCEPTIONS The Great War and the Ottoman Empire: Origins Ayşegül SEVER and Nuray BOZBORA Redefining the First World War within the Context of Clausewitz’s “Absolute War” Dystopia Burak GÜLBOY Unionist Failure to Stay out of the War in October-November 1914 Feroz AHMAD Austro-Ottoman Relations and the Origins of World War One, 1912-14: A Reinterpretation Gül TOKAY Ottoman Military Reforms on the eve of World War I Odile MOREAU The First World War in Contemporary Russian Histography - New Areas of Research Iskander GILYAZOV Summer-Autumn 2015 Volume XX - Number 2-3 ISSN 1300-8641 PERCEPTIONS Editor in Chief Ali Resul Usul Deputy Editor Birgül Demirtaş Managing Editor Engin Karaca Book Review Editor İbrahim Kaya English Language and Copy Editor Julie Ann Matthews Aydınlı International Advisory Board Bülent Aras Mustafa Kibaroğlu Gülnur Aybet Talha Köse Ersel Aydınlı Mesut Özcan Florian Bieber Thomas Risse Pınar Bilgin Lee Hee Soo David Chandler Oktay Tanrısever Burhanettin Duran Jang Ji Hyang Maria Todorova Ahmet İçduygu Ole Wæver Ekrem Karakoç Jaap de Wilde Şaban Kardaş Richard Whitman Fuat Keyman Nuri Yurdusev Homepage: http://www.sam.gov.tr The Center for Strategic Research (Stratejik Araştırmalar Merkezi- SAM) conducts research on Turkish foreign policy, regional studies and international relations, and makes scholarly and scientific assessments of relevant issues. It is a consultative body of the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs providing strategic insights, independent data and analysis to decision makers in government. As a nonprofit organization, SAM is chartered by law and has been active since May 1995. -

French Press, Public Opinion and the Murder of Franz Ferdinand In

French press, public opinion and the assassination of Franz Ferdinand (28 June-3 August 1914) How French society entered the Great war? Unlocking sources • The aim of this communication is quite simple: how new ways of getting access to digital contents (through technical process such as OCR and NER) give us the opportunity to understand how French society entered the First World War in August 1914? • Regarding this topic, I have studied both private archives and French press issues made available through the project Europeana 14-18 (chronologically from the 29 of June, the day after the assassination of Franz-Ferdinand , heir of the austro-hungarian monarchy in Sarajevo to the 3rd of August, the day of the declaration of war of Germany on France) • I have used two different technologies I will come back later on: the optical recognition of characters and the named entities recognition, a process we have developped thanks to another European project, Europeana Newspapers Unlocking sources • One of the main concern for me was also to assess the impact of the use of these automated processes applied to historical sources • This question is quite important as I strongly believe that the use of such technical process modify deeply our access and our understanding of historical sources (in other words how automated process lead to a new way of writing history) Starting point Emile Spring 1914 Starting point Letter sent to his family in law 31st of July 1914 French historiography • J-J Becker, How French entered the war, 1977) • If we consider the succession of events from the assassination of the archduke Franz-Ferdinand the 28th of June in Sarajevo to the declaration of war on France the 3rd of August, the point of view promoted by J.J. -

Leigh Chronicle," for This Week Only Four Pages, Fri 21 August 1914 Owing to Threatened Paper Famine

Diary of Local Events 1914 Date Event England declared war on Germany at 11 p.m. Railways taken over by the Government; Territorials Tue 04 August 1914 mobilised. Jubilee of the Rev. Father Unsworth, of Leigh: Presentation of illuminated address, canteen of Tue 04 August 1914 cutlery, purse containing £160, clock and vases. Leigh and Atherton Territorials mobilised at their respective drill halls: Leigh streets crowded with Wed 05 August 1914 people discussing the war. Accidental death of Mr. James Morris, formerly of Lowton, and formerly chief pay clerk at Plank-lane Wed 05 August 1914 Collieries. Leigh and Atherton Territorials leave for Wigan: Mayor of Leigh addressed the 124 Leigh Territorials Fri 07 August 1914 in front of the Town Hall. Sudden death of Mr. Hugh Jones (50), furniture Fri 07 August 1914 dealer, of Leigh. Mrs. J. Hartley invited Leigh Women's Unionist Association to a garden party at Brook House, Sat 08 August 1914 Glazebury. Sat 08 August 1914 Wingate's Band gave recital at Atherton. Special honour conferred by Leigh Buffaloes upon Sun 09 August 1914 Bro. R. Frost prior to his going to the war. Several Leigh mills stopped for all week owing to Mon 10 August 1914 the war; others on short time. Mon 10 August 1914 Nearly 300 attended ambulance class at Leigh. Leigh Town Council form Committee to deal with Tue 11 August 1914 distress. Death of Mr. T. Smith (77), of Schofield-street, Wed 12 August 1914 Leigh, the oldest member of Christ Church. Meeting of Leigh War Distress Committee at the Thu 13 August 1914 Town Hall. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

When Diplomats Fail: Aostrian and Rossian Reporting from Belgrade, 1914

WHEN DIPLOMATS FAIL: AOSTRIAN AND ROSSIAN REPORTING FROM BELGRADE, 1914 Barbara Jelavich The mountain of books written on the origins of the First World War have produced no agreement on the basic causes of this European tragedy. Their division of opinion reflects the situation that existed in June and July 1914, when the principal statesmen involved judged the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg throne, and its consequences from radically different perspectives. Their basic misunderstanding of the interests and viewpoints 'of the opposing sides contributed strongly to the initiation of hostilities. The purpose of this paper is to emphasize the importance of diplomatic reporting, particularly in the century before 1914 when ambassadors were men of influence and when their dispatches were read by those who made the final decisions in foreign policy. European diplomats often held strong opinions and were sometimes influenced by passions and. prejudices, but nevertheless throughout the century their activities contributed to assuring that this period would, with obvious exceptions, be an era of peace in continental affairs. In major crises the crucial decisions are always made by a very limited number of people no matter what the political system. Usually a head of state -- whether king, emperor, dictator, or president, together with those whom he chooses to consult, or a strong political leader with his advisers- -decides on the course of action. Obviously, in times of international tension these men need accurate information not only from their military staffs on the state of their and their opponent's armed forces and the strategic position of the country, but also expert reporting from their representatives abroad on the exact issues at stake and the attitudes of the other governments, including their immediate concerns and their historical background. -

World War I Timeline C

6.2.1 World War I Timeline c June 28, 1914 Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophia are killed by Serbian nationalists. July 26, 1914 Austria declares war on Serbia. Russia, an ally of Serbia, prepares to enter the war. July 29, 1914 Austria invades Serbia. August 1, 1914 Germany declares war on Russia. August 3, 1914 Germany declares war on France. August 4, 1914 German army invades neutral Belgium on its way to attack France. Great Britain declares war on Germany. As a colony of Britain, Canada is now at war. Prime Minister Robert Borden calls for a supreme national effort to support Britain, and offers assistance. Canadians rush to enlist in the military. August 6, 1914 Austria declares war on Russia. August 12, 1914 France and Britain declare war on Austria. October 1, 1914 The first Canadian troops leave to be trained in Britain. October – November 1914 First Battle of Ypres, France. Germany fails to reach the English Channel. 1914 – 1917 The two huge armies are deadlocked along a 600-mile front of Deadlock and growing trenches in Belgium and France. For four years, there is little change. death tolls Attack after attack fails to cross enemy lines, and the toll in human lives grows rapidly. Both sides seek help from other allies. By 1917, every continent and all the oceans of the world are involved in this war. February 1915 The first Canadian soldiers land in France to fight alongside British troops. April - May 1915 The Second Battle of Ypres. Germans use poison gas and break a hole through the long line of Allied trenches. -

The London Gazette, 5 February, 1915

1252 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 5 FEBRUARY, 1915. on the 29th day of October, 1910), are, on or before died in or about the month of September, 1913), are, the 10th day of March, 1915, to send by post, pre- on or before the 9th day of March, 1915, to send by- paid, to Mr. William Edward Farr, a member of the post, prepaid;, to° Mr. H. A. "Carter, of the firm, of firm of Messrs. Booth, Wade, Farr and Lomas- Messrs. Eallowes and Carter, of 39, Bedford-row, Walker, of Leeds, the Solicitors of the defendant, London, W.C., the Solicitor of ,the defendant, Charles Mary Matilda Ingham (the wife of Henry Ingham), Daniel William Edward Brown, the executor of the the administratrix of the estate of the said Eli deceased, their Christian and surname, addresses and Dalton, deceased, their Christian and surnames, descriptions, the full parfcieuJars of their claims, a addresses and descriptions1, the full particulars of statement of (their accounts, and the mature of the their claims, a statement of their accounts, and the securities (if any) held by them, or in default thereof nature of the securities (if any) -held by them, or in they will be peremptorily excluded from it-he* benefit of default thereof they will be peremptorily excluded the said order. Every creditor holding any security is from the benefit of the said judgment. Every credi- to produce the same at the Chambers of the said tor holding any security is to produce the same at Judge, Room No. 696, Royal 'Courts of Justice, the Chambers of Mr. -

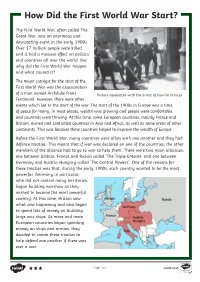

How Did the First World War Start?

How Did the First World War Start? The First World War, often called The Great War, was an enormous and devastating event in the early 1900s. Over 17 million people were killed and it had a massive effect on politics and countries all over the world. But why did the First World War happen and what caused it? The major catalyst for the start of the First World War was the assassination of a man named Archduke Franz Picture associated with the arrest of Gavrilo Princip Ferdinand. However, there were other events which led to the start of the war. The start of the 1900s in Europe was a time of peace for many. In most places, wealth was growing and people were comfortable and countries were thriving. At this time, some European countries, mainly France and Britain, owned and controlled countries in Asia and Africa, as well as some areas of other continents. This was because these countries helped to improve the wealth of Europe. Before the First World War, many countries were allies with one another and they had defence treaties. This meant that if war was declared on one of the countries, the other members of the alliance had to go to war to help them. There were two main alliances, one between Britain, France and Russia called ‘The Triple Entente’ and one between Germany and Austria-Hungary called ‘The Central Powers’. One of the reasons for these treaties was that, during the early 1900s, each country wanted to be the most powerful. Germany in particular, who did not control many territories, began building warships as they wished to become the most powerful country. -

The Assault in the Argonne and Vauquois with the Tenth Division, 1914-1915 Georges Boucheron Preface by Henri Robert

The Assault in the Argonne and Vauquois with the Tenth Division, 1914-1915 Georges Boucheron Preface by Henri Robert. Paris, 1917 Translated by Charles T. Evans © 2014 Charles. T. Evans 1 Translator’s Note: Although the translation is technically completed, I am always willing to reconsider specific translated passages if a reader has a suggestion. Brice Montaner, adjunct assistant professor of history at Northern Virginia Community College, has been of invaluable assistance in completing this translation. Because of copyright concerns, I have not included any maps as part of this translation, but maps will help you understand the Vauquois terrain, and so you should check those that are on the supporting website: worldwar1.ctevans.net/Index.html. 2 To my comrades of the 10th division fallen in the Argonne and at Vauquois, I dedicate these modest memoirs. G. B. 3 (7)1 To the reader. This is the name of a brave man. I am proud to be the friend of Georges Boucheron, and I thank him for having asked me to write a preface for his memoirs of the war. Is it really necessary to tell the public about those who fought to save France? Isn’t it enough to say a word or two about their suffering and their exploits for them to receive our sympathies? Boucheron has done well, so to speak, to write each day of his impressions. Like many other lawyers and like all other young Frenchmen, he has lived through the anxieties and dangers of this terrible war that was desired by Germany. Every night he noted facts, actions, words. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book.