E-Racing Together How Starbucks Reshaped and Deflected Racial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starbucks Corporation Valuation

Universidad de San Andrés Department of Economics Bachelor´s Degree in Economics Starbucks Corporation Valuation Author: Rodrigo Martínez Puente ID: 24136 Mentor: Gabriel Basaluzzo Buenos Aires, May 31st 2017 1 Contents 1. Abstract ............................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Economic Context & Industry Analysis .................................................................................. 7 3.1 Economic Context .................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Industry Analysis & Perspectives ...................................................................................... 9 3.2.1 Industry ............................................................................................................................... 9 3.2.2 Entry Barriers ................................................................................................................. 10 3.2.3 Trends ............................................................................................................................... 11 4. Starbucks ......................................................................................................................................... 13 4.1 Brief History........................................................................................................................... -

National Journalism Awards

George Pennacchio Carol Burnett Michael Connelly The Luminary The Legend Award The Distinguished Award Storyteller Award 2018 ELEVENTH ANNUAL Jonathan Gold The Impact Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB CBS IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY CAROL BURNETT. YOUR GROUNDBREAKING CAREER, AND YOUR INIMITABLE HUMOR, TALENT AND VERSATILITY, HAVE ENTERTAINED GENERATIONS. YOU ARE AN AMERICAN ICON. ©2018 CBS Corporation Burnett2.indd 1 11/27/18 2:08 PM 11TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards Los Angeles Press Club Awards for Editorial Excellence in A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 2017 and 2018, Honorary Awards for 2018 6464 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 870 Los Angeles, California 90028 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (310) 464-3577 E-mail: [email protected] Carper Du;mage Website: www.lapressclub.org Marie Astrid Gonzalez Beowulf Sheehan Photography Beowulf PRESS CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT: Chris Palmeri, Bureau Chief, Bloomberg News VICE PRESIDENT: Cher Calvin, Anchor/ Reporter, KTLA, Los Angeles TREASURER: Doug Kriegel, The Impact Award The Luminary The TV Reporter For Journalism that Award Distinguished SECRETARY: Adam J. Rose, Senior Editorial Makes a Difference For Career Storyteller Producer, CBS Interactive JONATHAN Achievement Award EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus GOLD International Journalist GEORGE For Excellence in Introduced by PENNACCHIO Storytelling Outside of BOARD MEMBERS Peter Meehan Introduced by Journalism Joe Bell Bruno, Freelance Journalist Jeff Ross MICHAEL Gerri Shaftel Constant, CBS CONNELLY CBS Deepa Fernandes, Public Radio International Introduced by Mariel Garza, Los Angeles Times Titus Welliver Peggy Holter, Independent TV Producer Antonio Martin, EFE The Legend Award Claudia Oberst, International Journalist Lisa Richwine, Reuters For Lifetime Achievement and IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY Ina von Ber, US Press Agency Contributions to Society CAROL BURNETT. -

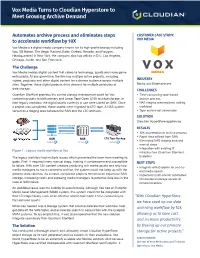

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

The Industrial Eater

THE INDUSTRIAL EATER: AN EXPLORATION INTO THE UNDERLYING VALUES MOTIVATING AMERICAN FAST FOOD CONSUMPTION A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the Degree of Bachelor of Business Administration by Jordan L. Templeton June 2010 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Business Administration Dr. Jane Sojka Professor, Marketing Thesis Advisor Dr. Raymond Frost Professor, Management Information Systems Honors Tutorial College Director of Studies, Business Administration Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 The Link between Fast Food & Industrial Agriculture ................................................... 2 Fast Food and Expanding Waste Lines ....................................................................... 4 Changing Family Structure and Increased Reliance on Fast Food ......................... 6 Increased Availability and Affordability of Fast Food ........................................... 6 Increased Portion Sizes ........................................................................................... 9 Child Targeted and Misleading Food Advertisements ......................................... 11 Increased Sedentary Lifestyles ............................................................................ -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ORR PARTNERS ENGAGED BY VOX MEDIA Reston, VA (January 12, 2016) — Vox Media has selected Orr Partners to manage the expansion of their 1201 Connecticut Avenue office in Washington, DC. The modern media company will utilize the additional space to accommodate the rapid growth of its major brands. The improvements include: • Seating for approximately 100 staff • Recording facilities • Conference and teaming areas • Ancillary / teaming space “We are excited we were selected for this exciting and challenging project,” commented Scott Siegel, President of Orr Partners. “We appreciate Vox’s confidence in our team.” The project will commence immediately with assembly of the full project team and completion of the design. “Vox has a great energy about them,” stated Clif White, Senior Project Manager for Orr Partners. “I look forward to working closely with the project team to deliver a project we will all be proud of.” The project will deliver in spring of 2016. ABOUT ORR PARTNERS Orr Partners, an award-winning Project Management firm in Reston, Virginia, is a leading provider of owner's representation services. Specializing in complex project management, Orr Partners provides services for a diverse client base in multiple disciplines including corporate tenant improvements, multi-family, educational, religious, industrial, healthcare, manufacturing, and public sector work. For more detailed information, please email [email protected], visit orrpartners.com or call Scott Siegel at 703-289-2132. For more information on Orr’s property management business, MacGregor Property Management, visit magregorpm.com. For more information on Orr’s safety and QA/QC business, NSBI, visit nsbuilding.com. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate

NEW YORK, THE REAL ESTATE Jerry Speyer Michael Bloomberg Stephen Ross Marc Holliday Amanda Burden Craig New- mark Lloyd Blankfein Bruce Ratner Douglas Durst Lee Bollinger Michael Alfano James Dimon David Paterson Mort Zuckerman Edward Egan Christine Quinn Arthur Zecken- dorf Miki Naftali Sheldon Solow Josef Ackermann Daniel Boyle Sheldon Silver Steve Roth Danny Meyer Dolly Lenz Robert De Niro Howard Rubinstein Leonard Litwin Robert LiMandri Howard Lorber Steven Spinola Gary Barnett Bill Rudin Ben Bernanke Dar- cy Stacom Stephen Siegel Pam Liebman Donald Trump Billy Macklowe Shaun Dono- van Tino Hernandez Kent Swig James Cooper Robert Tierney Ian Schrager Lee Sand- er Hall Willkie Dottie Herman Barry Gosin David Jackson Frank Gehry Albert Behler Joseph Moinian Charles Schumer Jonathan Mechanic Larry Silverstein Adrian Benepe Charles Stevenson Jr. Michael Fascitelli Frank Bruni Avi Schick Andre Balazs Marc Jacobs Richard LeFrak Chris Ward Lloyd Goldman Bruce Mosler Robert Ivanhoe Rob Speyer Ed Ott Peter Riguardi Scott Latham Veronica Hackett Robert Futterman Bill Goss Dennis DeQuatro Norman Oder David Childs James Abadie Richard Lipsky Paul del Nunzio Thomas Friedan Jesse Masyr Tom Colicchio Nicolai Ourouso! Marvin Markus Jonathan Miller Andrew Berman Richard Brodsky Lockhart Steele David Levinson Joseph Sitt Joe Chan Melissa Cohn Steve Cuozzo Sam Chang David Yassky Michael Shvo 100The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate Bloomberg, Trump, Ratner, De Niro, the Guy Behind Craigslist! They’re All Among Our 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate ower. Webster’s Dictionary defines power as booster; No. 15 Edward Egan, the Catholic archbish- Governor David Paterson (No. -

The 2020 New York Emmy® Award Nominees 1

The 2020 New York Emmy® Award Nominees THE 63rdANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED THIS MORNING! New York, NY – Tuesday, February 25, 2020. The 63rd Annual New York Emmy® Award nominations took place this morning at the studios of (CUNY-TV). Hosting the announcement was NJ Burkett, President, NY NATAS. Presenting the nominees were Emmy® Award-nominee Liliana Ayende, Weather Anchor (Univision 41); Emmy® Award-winner Janice Huff, Chief Meteorologist, (WNBC-TV); Emmy® Award-winner Virginia Huie, Reporter, (News 12 Long Island); and Emmy® Award-winner Marvin Scott, Senior Correspondent, (WPIX-TV). Total Number of Nominated Entries WNJU Telemundo 47 68 New York City College of Technology - CUNY 2 MSG Network 40 New York Football Giants 2 Spectrum News NY1 – News 38 NET-TV 2 WPIX-TV 38 Spectrum News Rochester 2 WXTV Univision 41 – News 36 WJLP-TV 2 WNBC-TV News 29 WLIW 21 2 YES Network 27 WRGB CBS 6 2 News 12 Westchester 26 WSKG 2 SNY 25 WSYR-TV, Syracuse, NY 2 Newsday 23 WTEN-TV 2 WCBS-TV 20 4th Coast Productions 1 New York Jets 19 ba_sk 1 WABC-TV 19 Black Iris Project 1 News 12 Long Island 17 BronxNet 1 CUNY-TV 17 Brooklyn Free Speech 1 WNYW FOX 5 15 Buzz Feed 1 THIRTEEN 10 BuzzFeed News 1 News 12 New Jersey 10 Diva Communications, Inc. 1 WXTV Univision 41 – Promotions 9 Ember Music Productions 1 New York Yankees 8 Hollywoodland Productions 1 NYC Life 8 John Gore Organization 1 Mac Premo, Inc 7 Kean University 1 News 12 Connecticut 6 LCM247 1 Pegula Sports and Entertainment 6 Manhattan College 1 WRNN-TV 6 Maroonhorizon Media 1 BRIC TV 5 Miracle on 42nd Street, Inc 1 News 12 The Bronx 5 News 12 Hudson Valley 1 NJ Advance Media 5 NewYork-Presbyterian's Health Matters 1 WIVB-TV 5 NJTV 1 WKBW 5 NYC & Company 1 WNYT 5 Provost Studio 1 WRGB-TV 4 Quanta Magazine 1 Broadway.com 4 Sammi Mendenhall Creative, Inc. -

Season 2 of NO PASSPORT REQUIRED with Marcus Samuelsson Explores the Food and Culture of America’S Immigrant Communities

Season 2 of NO PASSPORT REQUIRED with Marcus Samuelsson Explores the Food and Culture of America’s Immigrant Communities Full Schedule and Episode Descriptions CHEFS MARCUS AND VIVIAN: A TASTE OF WHAT’S NEXT Friday, December 13, 8:30-9:00 p.m. ET Chefs Vivian Howard and Marcus Samuelsson have been traveling around the country to better understand immigrant foodways. While in Los Angeles, the two chefs visit Grand Central Market to meet new friends that contribute to the richness of L.A.’s food scene. Vivian’s new series SOMEWHERE SOUTH premieres on PBS in 2020. NO PASSPORT REQUIRED - Season 2 Preview “Seattle” – Friday, December 13, 9:00-10:00 p.m. ET Marcus explores Seattle’s thriving Filipino community, learning about their longstanding connection to the city and meeting young Filipino-American chefs who are bringing their passion to the city's vibrant food scene. Along the way, he discovers how their cuisine combines the unique flavors of the island nation’s complex history, which includes Chinese, Spanish, Japanese and American influences. Come along as Marcus visits a variety of restaurants — from food trucks to a trendy speakeasy to cutting-edge fine dining establishments — and samples delicacies including chicken adobo, oyster ceviche, pork blood stew and a unique but tasty cheesecake made with purple yam. “Los Angeles” – Monday, January 20, 9:00-10:00 p.m. ET - Season 2 Premiere Marcus visits Los Angeles, where the largest Armenian community outside of the homeland thrives in the foothills north of downtown L.A. Resilient and entrepreneurial, Armenians are scattered across the world, and Marcus meets Armenians from Russia, Lebanon, Syria, Ethiopia and Egypt. -

Vox Media Flourishes with Scalable Solutions and Support from Chesapeake Systems

VOX MEDIA FLOURISHES WITH SCALABLE SOLUTIONS AND SUPPORT FROM CHESAPEAKE SYSTEMS Archive, asset management, workflow automation, and storage solutions have paved the path for Vox Media’s future growth, providing new functionality that addresses rising trends and viable revenue streams for the company. CASE STUDY Photos by ©Chris Leonard, courtesy of Gensler WWW.CHESA.COM CASE STUDY VOX MEDIA OVERVIEW Premium digital media company Vox Media has grown exponentially over the past 12 years, currently encompassing eight authoritative editorial networks – SB Nation, The Verge, Polygon, Curbed, Eater, Racked, Vox, and Recode. In addition to its position as a powerhouse new media company, Vox Media’s underlying technology has played a key role in the company’s success. Vox Media’s brands are built on the company’s proprietary modern media stack, Chorus, and ad marketplace, Concert. 1 CHESA CHESA.COM 410.752.7729 CASE STUDY VOX MEDIA ABOUT VOX MEDIA On the content creation side, Vox Media’s emphasis on visual impact has driven tremendous growth. For the past six years, Marcos Bueno, Head of Media Technology based at the company’s New York City headquarters, has spearheaded the infrastructure used by Vox Creative, the company’s branded content division. Like all video producers today, the Vox Media studio team requires a robust, reliable, and secure post-production pipeline for effective asset management and archiving. As content creation continues to explode at Vox Media, Bueno has come to rely on Chesapeake Systems as an engaged partner for providing solutions to the team’s evolving needs. “We started working with Chesapeake about four years ago,” Bueno recalls. -

Digital Strategy: Example Deliverable

Digital Strategy: Example Deliverable 1 Contents • Product Overview • Case studies • Key recommendations (excerpt) 2 A go forward strategy project would deliver on three key objectives A synthesized set of key facts and insights to 1 inform, guide and shape the digital strategy and its key recommendations and proposed actions The effort A set of concrete, actionable deliverables X would be 2 can use immediately or in the near-term to guided by maximize X X’s vision and goals An actionable, long-term digital strategy to 3 meet and exceed X’s digital goals over time via a phased plan across key dimensions 3 The strategy effort would provide actionable deliverables and recommendations organized around four key dimensions Key dimensions High-level overview Digital Strategy • A clear, actionable strategy to maximize X’s impact given current and potential resources (e.g., staff, products, brand, partners) Digital • A digital ecosystem that includes effective, productive Ecosystem connections between X’s products and lays out clear, effective connections to deliver X’s goals A Products • A recommended path forward for X’s current and potential A products B Products • A recommended path forward for X’s current and potential B products 4 The effort would provide actionable deliverables and recom- mendations for the near, medium and long-term time frames Long-term Medium-term Near-term Time horizon: • ~0-4 months • ~4-18 months • ~18-36 months Key • Near-term opportunities • Opportunities that use • Strategically critical considerations: that can -

The Carnegie Center'sneighbor

We're Here for You, & We're Here to Stay Dear Carnegie friends! As we continue our journey through the COVID era, please know that the Carnegie Center is here to stay. STAFF As you will see in this new catalog, we are offering a full array of nonfiction, fiction, poetry, and world- language classes—all available only online. We hope you'll find them helpful as you seek community and Neil Chethik, Executive Director make sense of all that's going on. Sarah Chapman, Program Director Erica Cook, Outreach Volunteer Director We are also expanding our tutoring and other children's programs to help families make it through the & pandemic. We understand that this school year will be different than any other. We will work with parents Tom Eblen, Literary Arts Liaison throughout the year to determine children's urgent academic needs. Then, we'll do our best to gather the Randi Ewing, Outreach Associate resources to meet them. Kimber Gray, Multimedia & Marketing Associate Maddy Hamilton, Rental Coordinator If you have kept your job and health during the pandemic, we need your help. More Lexington children Outreach Associate than ever will need tutors. Please contact Tutoring Director Carol Jordan ([email protected]) & if you'd be willing to tutor on Zoom this school year. Brittany Jackson, Development Associate Marcia Thornton Jones, Tutoring Associate Also, with many people out of work, your donations are especially appreciated. To donate to Carnegie, & Author Academy Coordinator visit the Donate button on our homepage, wwwCarnegieCenterLex.org. Carol Jordan, Tutoring Director Jennifer Mattox, Development Director Our plan is to hold the Fall season on Zoom (through Thanksgiving) and decide then whether we can bring the public back to the building in January.