Sociology Following Durkheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starbucks Corporation Valuation

Universidad de San Andrés Department of Economics Bachelor´s Degree in Economics Starbucks Corporation Valuation Author: Rodrigo Martínez Puente ID: 24136 Mentor: Gabriel Basaluzzo Buenos Aires, May 31st 2017 1 Contents 1. Abstract ............................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Economic Context & Industry Analysis .................................................................................. 7 3.1 Economic Context .................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Industry Analysis & Perspectives ...................................................................................... 9 3.2.1 Industry ............................................................................................................................... 9 3.2.2 Entry Barriers ................................................................................................................. 10 3.2.3 Trends ............................................................................................................................... 11 4. Starbucks ......................................................................................................................................... 13 4.1 Brief History........................................................................................................................... -

Identities Bought and Sold, Identity Received As Grace

IDENTITIES BOUGHT AND SOLD, IDENTITY RECEIVED AS GRACE: A THEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF AND ALTERNATIVE TO CONSUMERIST UNDERSTANDINGS OF THE SELF By James Burton Fulmer Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion December, 2006 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Paul DeHart Professor Douglas Meeks Professor William Franke Professor David Wood Professor Patout Burns ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all the members of my committee—Professors Paul DeHart, Douglas Meeks, William Franke, David Wood, and Patout Burns—for their support and guidance and for providing me with excellent models of scholarship and mentoring. In particular, I am grateful to Prof. DeHart for his careful, insightful, and challenging feedback throughout the writing process. Without him, I would have produced a dissertation on identity in which my own identity and voice were conspicuously absent. He never tried to control my project but rather always sought to make it more my own. Special thanks also to Prof. Franke for his astute observations and comments and his continual interest in and encouragement of my project. I greatly appreciate the help and support of friends and family. My mom, Arlene Fulmer, was a generous reader and helpful editor. James Sears has been a great friend throughout this process and has always led me to deeper thinking on philosophical and theological matters. Jimmy Barker, David Dault, and Eric Froom provided helpful conversation as well as much-needed breaks. All my colleagues in theology helped with valuable feedback as well. -

Alcohol and Getting Older: Ageing Well

Reviewing your drinking Ask your pharmacist or doctor whether it’s safe to www.alcoholireland.ie mix your medicine with alcohol. If you are worried about your alcohol use, talk to your GP. S/he will be able to offer you information For general information and advice, and refer you to the support or service on alcohol go to best suited to your needs. Alcohol and Talk to family and friends who you think could be www.alcoholireland.ie of help. Getting Older: It’s never too late to make the changes that will make your life even better. Ageing Well For general information on alcohol go to www.alcoholireland.ie If you are worried about your alcohol use, talk to your GP www.alcoholireland.ie There are many Your health and alcohol How much is too much? benefits Many of us enjoy a drink particularly in a social The guidelines for low-risk drinking are up occasion with friends or family: associated to 14 units a week for a woman (11 standard drinks) and 21 units for a man (17 standard • As we age, however, our ability to break down with reducing drinks), spread out over the week with at alcohol is reduced and we are more susceptible your drinking least 2/3 days alcohol free. These guidelines to the effects of alcohol. As a result, a person apply to healthy adults - if you are ill or on can develop problems with alcohol as they medication, these low-risk guidelines may be grow older, even when drinking habits remain too high. -

Beer & Cider Wine C Ockt Ails Gin Goblet S Jugs

COCKTAILS GIN GOBLETS JUGS JUGS GIN GOBLETS COCKTAILS BEER & CIDER POT PINT WINE 125ml Bott ON TAP COCKTAILS 285ML 570ML CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING — — CLASSICS AVAILABLE PLEASE ASK ROTHBURY ESTATE SPARKLING NV HUNTER VALLEY NSW 10 45 FURPHY REFRESHING ALE 6.5 12 STRAWBERRY SWING 21 AZAHARA MOSCATO NV RED CLIFFS VIC 10 45 FURPHY CRISP LAGER 6.5 12 BOMBAY SAPPHIRE, PAMA LIQUEUR, LEMON, STRAWBERRIES, SUGAR T’GALLANT PROSECCO NV YARRA VALLEY VIC 12 58 CARLTON DRAUGHT 7 13 CHANDON BRUT NV YARRA VALLEY VIC 14 82 WATERMELON SUGAR 20 BALTER XPA 7.5 14 EL JIMADOR, WATERMELON, LIME, SUGAR & SALT RIM CHANDON BRUT ROSÉ NV YARRA VALLEY VIC 14 82 JANSZ BRUT ROSÉ MAGNUM NV TASMANIA 140 LITTLE CREATURES PALE ALE 7.5 14 AMALFI SOUR 21 42 BELOW, BASS & FLINDERS LIMONCELLO, VEUVE CLICQUOT BRUT NV CHAMPAGNE FRANCE 135 PANHEAD SUPERCHARGER IPA 7.5 14 LEMON, SUGAR, EGG WHITE ASAHI SUPER DRY 400ML 13 NANA’S NIGHTCAP 21 ROSÉ & DESSERT 150ml 250ml Bott APPLE PIE MOONSHINE, BACARDI SPICED, APPLE PUREE, WHITE RABBIT DARK ALE 7.5 14 2020 SQUEALING PIG ROSÉ MARLBOROUGH NZ 11 17 52 LEMON, EGG WHITE PIPSQUEAK APPLE CIDER 7 13 2019 DOMAINE DE TRIENNES ROSÉ PROVENCE FRANCE 12 20 60 SPLICE UP YOUR LIFE 20 BREWMANITY TANGO & SPLASH JUICY LAGER 6.5 12 42 BELOW, MIDORI, PEACH SYRUP, PINEAPPLE, LIME 2019 LA LA LAND ROSÉ VIC 43 BIG FREEZE FIGHT MND BEER COFFEE NEGRONI 22 2017 CAPE MENTELLE ROSÉ MARGARET RIVER WA 62 FOUR PILLARS RARE DRY, CAMPARI, SWEET VERMOUTH, 2019 ROGERS & RUFUS ROSÉ MAGNUM 110 COLD BREW COFFEE ASK ABOUT OUR RANGE OF BOTTLES/CANS BAROSSA VALLEY SA MOCKTAIL -

National Journalism Awards

George Pennacchio Carol Burnett Michael Connelly The Luminary The Legend Award The Distinguished Award Storyteller Award 2018 ELEVENTH ANNUAL Jonathan Gold The Impact Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB CBS IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY CAROL BURNETT. YOUR GROUNDBREAKING CAREER, AND YOUR INIMITABLE HUMOR, TALENT AND VERSATILITY, HAVE ENTERTAINED GENERATIONS. YOU ARE AN AMERICAN ICON. ©2018 CBS Corporation Burnett2.indd 1 11/27/18 2:08 PM 11TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards Los Angeles Press Club Awards for Editorial Excellence in A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 2017 and 2018, Honorary Awards for 2018 6464 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 870 Los Angeles, California 90028 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (310) 464-3577 E-mail: [email protected] Carper Du;mage Website: www.lapressclub.org Marie Astrid Gonzalez Beowulf Sheehan Photography Beowulf PRESS CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT: Chris Palmeri, Bureau Chief, Bloomberg News VICE PRESIDENT: Cher Calvin, Anchor/ Reporter, KTLA, Los Angeles TREASURER: Doug Kriegel, The Impact Award The Luminary The TV Reporter For Journalism that Award Distinguished SECRETARY: Adam J. Rose, Senior Editorial Makes a Difference For Career Storyteller Producer, CBS Interactive JONATHAN Achievement Award EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus GOLD International Journalist GEORGE For Excellence in Introduced by PENNACCHIO Storytelling Outside of BOARD MEMBERS Peter Meehan Introduced by Journalism Joe Bell Bruno, Freelance Journalist Jeff Ross MICHAEL Gerri Shaftel Constant, CBS CONNELLY CBS Deepa Fernandes, Public Radio International Introduced by Mariel Garza, Los Angeles Times Titus Welliver Peggy Holter, Independent TV Producer Antonio Martin, EFE The Legend Award Claudia Oberst, International Journalist Lisa Richwine, Reuters For Lifetime Achievement and IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY Ina von Ber, US Press Agency Contributions to Society CAROL BURNETT. -

Neurochemical Mechanisms Underlying Alcohol Withdrawal

Neurochemical Mechanisms Underlying Alcohol Withdrawal John Littleton, MD, Ph.D. More than 50 years ago, C.K. Himmelsbach first suggested that physiological mechanisms responsible for maintaining a stable state of equilibrium (i.e., homeostasis) in the patient’s body and brain are responsible for drug tolerance and the drug withdrawal syndrome. In the latter case, he suggested that the absence of the drug leaves these same homeostatic mechanisms exposed, leading to the withdrawal syndrome. This theory provides the framework for a majority of neurochemical investigations of the adaptations that occur in alcohol dependence and how these adaptations may precipitate withdrawal. This article examines the Himmelsbach theory and its application to alcohol withdrawal; reviews the animal models being used to study withdrawal; and looks at the postulated neuroadaptations in three systems—the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmitter system, the glutamate neurotransmitter system, and the calcium channel system that regulates various processes inside neurons. The role of these neuroadaptations in withdrawal and the clinical implications of this research also are considered. KEY WORDS: AOD withdrawal syndrome; neurochemistry; biochemical mechanism; AOD tolerance; brain; homeostasis; biological AOD dependence; biological AOD use; disorder theory; biological adaptation; animal model; GABA receptors; glutamate receptors; calcium channel; proteins; detoxification; brain damage; disease severity; AODD (alcohol and other drug dependence) relapse; literature review uring the past 25 years research- science models used to study with- of the reasons why advances in basic ers have made rapid progress drawal neurochemistry as well as a research have not yet been translated Din understanding the chemi- reluctance on the part of clinicians to into therapeutic gains and suggests cal activities that occur in the nervous consider new treatments. -

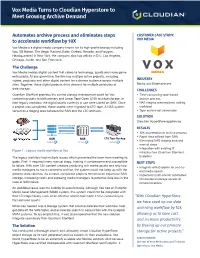

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

Peter Svensson Får Platinagitarren 2017

Peter Svensson 2017-10-18 07:00 CEST Peter Svensson får Platinagitarren 2017 Låtskrivaren och gitarristen Peter Svensson får Stims utmärkelse Platinagitarren för sina framgångar som låtskrivare genom åren och under 2016. Peter Svensson var med och grundade The Cardigans och har skapat musik i mer än 20 år. Han har även varit låtskrivare åt en rad stora internationella artister. Bland de största hitsen senaste åren kan nämnas Ariana Grandes Love Me Harder (3a i USA), USA-ettan och monsterhiten Can't Feel My Face och In The Night (12 i USA), båda framförda av The Weeknd. 1992 bildade hårdrockaren Peter Svensson gruppen The Cardigans tillsammans med Magnus Sveningsson. Fyra år senare slog bandet igenom stort internationellt med världshiten "Lovefool". Världsturneer och ytterligare hits följer, såsom "My Favourite game", "Erase/Rewind" och "I need some fine wine and you, you need to be nicer". - Det känns helt fantastiskt att bli tilldelad Stims Platinagitarr!! Bara att få ingå i den skara av låtskrivare som tidigare fått utmärkelsen gör en stolt. Det är verkligen uppmuntrande och en fin bekräftelse på att det man gör uppskattas. Nu är det bara att hoppas på att jag kan leva upp till det hela och få till det igen, säger Peter Svensson. Parallellt med The Cardigans skrev Peter Svensson hits åt exempelvis Titiyo (Come Along), Lisa Miskovsky och det egna sidoprojektet Paus tillsammans med Joakim Berg från Kent. Peter Svensson har även etablerat sig som låtskrivare åt en rad stora internationella artister såsom One Direction, Ellie Goulding och The Weeknd. Bland Peters största hits de senaste åren kan nämnas Ariana Grandes Love Me Harder (3a i USA), Meghan Trainors Me Too (13e plats i USA) och USA- ettan "Can't Feel My Face" och "In The Night" (12e plats i USA), båda framförda av The Weeknd. -

E-Racing Together How Starbucks Reshaped and Deflected Racial

Public Relations Review 45 (2019) 101773 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Public Relations Review journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pubrev E-Racing together: How starbucks reshaped and deflected racial conversations on social media T ⁎ Alison N. Novaka, , Julia C. Richmondb a Rowan University, 301 High Street, 325, Glassboro, NJ, United States b Drexel University, 3141 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: In March 2015, Starbucks introduced its #RaceTogether campaign to encourage patrons to Starbucks discuss race and ethnicity in global culture. Public reaction to #RaceTogether was largely critical Twitter and resulted in Starbucks' abandoning the campaign within a year. Through an analysis of 5000 Reputation management #RaceTogether tweets, this study examines how users engaged the campaign and each other. Race This study draws three conclusions. First, most #RaceTogether posts featured extremist and Brand racist positions. Second, #RaceTogether posts deflected race conversations and critiqued the Social media organizations role in national racial discourses. Finally, posts in the digital space critiqued Starbucks as a location for inter-racial dialogue because of brand perception. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, com- mercial, or not-for-profit sectors. 1. Introduction In March 2015, Starbucks introduced its #RaceTogether campaign designed to encourage patrons to openly discuss and debate the contemporary treatment and place of race and ethnicity in global culture. In the aftermath of police violence targeted towards American minorities (and specifically Black Americans), the corporation intended to provide a physical and digital space forcus- tomers to reflect on recent events (Hernandez, 2015). -

From Girlfriend to Gamer: Negotiating Place in the Hardcore/Casual Divide of Online Video Game Communities

FROM GIRLFRIEND TO GAMER: NEGOTIATING PLACE IN THE HARDCORE/CASUAL DIVIDE OF ONLINE VIDEO GAME COMMUNITIES Erica Kubik A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2010 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Advisor Amy Robinson Graduate Faculty Representative Kristine Blair Donald McQuarie ii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor The stereotypical video gamer has traditionally been seen as a young, white, male; even though female gamers have also always been part of video game cultures. Recent changes in the landscape of video games, especially game marketers’ increasing interest in expanding the market, have made the subject of women in gaming more noticeable than ever. This dissertation asked how gender, especially females as a troubling demographic marking difference, shaped video game cultures in the recent past. This dissertation focused primarily on cultures found on the Internet as they related to video game consoles as they took shape during the beginning of the seventh generation of consoles, between 2005 and 2009. Using discourse analysis, this dissertation analyzed the ways gendered speech was used by cultural members to define not only the limits and values of a generalizable video game culture, but also to define the idealized gamer. This dissertation found that video game cultures exhibited the same biases against women that many other cyber/digital cultures employed, as evidenced by feminist scholars of technology. Specifically, female gamers were often perceived as less authoritative of technology than male gamers. This was especially true when the concept “hardcore” was employed to describe the ideals of gaming culture. -

Control State News

Monday, October 28, 2019 2900 S. Quincy St., Suite 800 Arlington, VA 22206 www.nabca.org • State Sen. Orr vows to renew push to take State of Alabama out of retail alcohol sales • Historic Soda Rock winery destroyed as Kincade fire has wine country under siege TODAY’S • Canada: Do we need a federal Alcohol Act in Canada to better regulate the substance? HIGHLIGHTS • Taking direct consumer wine distribution to a new level • What’s the drinking age on international flights? CONTROL STATE NEWS The release said during the 2019 Oregon Legislation session, bills were introduced about wine labeling, fruit OR: New Wine Council Forms In Oregon sales outside Oregon, purity standards and creating new licensure laws. One of those was SB111, which was News, Radio 1240 KQEN sponsored by the Oregon Winegrowers Association. It By Kyle Bailey October 28, 2019 was the catalysis for opposition according to the release. It said that the coalition that defeated the legislation is A new wine organization has begun in Oregon. now the OWC. The release said the group believes that The Oregon Wine Council has formed with a board of the OWA “has not represented our best interests, nor the directors and members representing the wine industry interests of the statewide wine industry”. statewide. A release from the OWC said the group Find out more about the new organization by going to formed “from the coalition who defended the wine www.oregonwinecouncil.org. Tuesday’s Inside Douglas industry from anti-competitive wine legislation during County on News Radio 1240 KQEN will focus on the the 2019 Oregon legislature”. -

The Industrial Eater

THE INDUSTRIAL EATER: AN EXPLORATION INTO THE UNDERLYING VALUES MOTIVATING AMERICAN FAST FOOD CONSUMPTION A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the Degree of Bachelor of Business Administration by Jordan L. Templeton June 2010 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the Department of Business Administration Dr. Jane Sojka Professor, Marketing Thesis Advisor Dr. Raymond Frost Professor, Management Information Systems Honors Tutorial College Director of Studies, Business Administration Dr. Jeremy Webster Dean, Honors Tutorial College Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 The Link between Fast Food & Industrial Agriculture ................................................... 2 Fast Food and Expanding Waste Lines ....................................................................... 4 Changing Family Structure and Increased Reliance on Fast Food ......................... 6 Increased Availability and Affordability of Fast Food ........................................... 6 Increased Portion Sizes ........................................................................................... 9 Child Targeted and Misleading Food Advertisements ......................................... 11 Increased Sedentary Lifestyles ............................................................................