Independent Directors in Asia Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cfa Society Ireland Career Guide Cfa Society Ireland Career Guide Cfa Society Ireland

CFA SOCIETY IRELAND CAREER GUIDE CFA SOCIETY IRELAND CAREER GUIDE CFA SOCIETY IRELAND CFA SOCIETY IRELAND CFA Society Ireland is the Irish professional body for those engaged in investment analysis and portfolio management in Ireland. CFA Society Ireland is a member society of CFA Institute, the global association of investment professionals that sets the standard for excellence in the industry. CFA Society Ireland currently has over 500 members across three membership categories – Regular, Affiliate, and Local. Annually we typically have over 500 candidates in the CFA® Program, many of whom join the society as they near completion of Level III. Enrolment in, and completion of, the CFA Program exams are not a requirement of membership, and we actively encourage Irish investment professionals to join the society. The objectives of the society are: Benefits of CFA Society Ireland Membership include the following: • To achieve, foster and maintain high standards of professional ability and • To network with peers in the industry. practice in investment analysis, portfolio management and related disciplines • To be part of an effectual and common in Ireland. voice to develop and protect the interests of the profession. • To encourage the creation and interchange of ideas and information among those • To stay abreast of trends that affect the engaged in these activities. industry in your market. • To advance public understanding of • To take advantage of local professional their functions and techniques and the development opportunities. operation of security and other investment markets. • To socialize with industry insiders . • To support and promote the interests • To access additional resources, such as of the investment community. -

Elements of an Investment Policy Statement for Individual Investors

ELEMENTS OF AN INVESTMENT POLICY STATEMENT FOR INDIVIDUAL INVESTORS ELEMENTS OF AN INVESTMENT POLICY STATEMENT FOR INDIVIDUAL INVESTORS © 2010 CFA Institute. All rights reserved. CFA Institute is the global association of investment professionals that sets the standards for professional excellence. We are a champion for ethical behavior in investment markets and a respected source of knowledge in the global financial community. Our mission is to lead the investment profession globally by promoting the highest standards of ethics, education, and professional excellence for the ultimate benefit of society. ISBN: 978-0-938367-31-4 May 2010 Contents INTRODUCTION 1 1. Scope and Purpose 3 1a. Define the context. 3 1b. Define the investor. 3 1c. Define the structure. 4 2. Governance 6 2a. Specify who is responsible for determining investment policy, executing investment policy, and monitoring the results of implementation of the policy. 6 2b. Describe the process for reviewing and updating the IPS. 6 2c. Describe responsibility for engaging and discharging external advisers. 7 2d. Assign responsibility for determination of asset allocation, including inputs used and criteria for development of input assumptions. 7 2e. Assign responsibility for risk management, monitoring, and reporting. 8 3. Investment, Return, and Risk Objectives 9 3a. Describe the overall investment objective. 9 3b. State the return, distribution, and risk requirements. 9 3c. Define the risk tolerance of the investor. 11 3d. Describe relevant constraints. 12 3e. Describe other considerations relevant to investment strategy. 14 © 2010 CFA INSTITUTE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. iii 4. Risk Management 16 4a. Establish performance measurement and reporting accountabilities. 16 4b. Specify appropriate metrics for risk measurement and evaluation. -

2020 Proxy Statement & Notice of Annual

Republication Date: 3 August 2020 Pages Amended: 54 & 55 Footnote on the bottom of page 55 details the changes made. 2020 PROXY STATEMENT & NOTICE OF ANNUAL MEETING OF MEMBERS 17 May 2020 © 2020 CFA Institute. All Rights Reserved. This page intentionally left blank. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR DEAR FELLOW MEMBERS, In this proxy statement, we present candidates for the Board of Governors of CFA Institute, as well as proposed changes to the Articles of Incorporation and Bylaws to help continue to improve our governance. We would sincerely appreciate it if you would take the time to review these materials and vote: Every vote counts and makes a difference. I would like to update you on the Board’s approach to governance. We strive, wherever possible and appropriate, to follow public company standards of governance. While we are a not-for-profit entity, we believe that, as advocates for integrity in the public markets and in financial reporting, we should follow public company standards. We have adopted a policy of rotating our auditors, and thus our Annual Report and financials have been audited by KPMG LLP for fiscal year 2019. Our Board committee structure mirrors that of a public company, and we believe this approach gives us greater focus and allows us to best utilize the varied and deep skills of our all- volunteer Board. The proposed changes to the Bylaws at the Annual Meeting of Members will enable the Chair to be recommended by the Board and elected annually by the Diane C. Nordin, CFA membership to serve consecutive one-year terms. -

Standards of Practice Handbook Standards of Practice Standards of Practice Handbook

2014 STANDARDS OF PRACTICE OF STANDARDS HANDBOOK STANDARDS OF PRACTICE HANDBOOK ELEVENTH EDITION 2014 ELEVENTH EDITION CFA INSTITUTECFA Standards of Practice Handbook ELEVENTH EDITION 2014 ©2014, 2010, 2006, 2005, 1999, 1996, 1992, 1990, 1988, 1986, 1985 (supplement), 1984, 1982, by CFA Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, record- ing, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission of the copyright holder. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to: Copyright Permissions, CFA Institute, 915 East High Street, Charlottesville, Virginia 22902. CFA®, Chartered Financial Analyst®, CIPM®, Claritas® and GIPS® are just a few of the trademarks owned by CFA Institute. To view a list of CFA Institute trade- marks and the Guide for the Use of CFA Institute Marks, please visit our website at www.cfainstitute.org. ISBN: 978-0-938367-85-7 16 June 2014 (Corrected September 2014) Contents Preface................................................................................................... v Ethics and the Investment Industry ............................................................. 1 CFA Institute Code of Ethics and Standards of Professional Conduct .................. 7 Standard I: Professionalism A. Knowledge of the Law ...............................................................13 B. Independence and Objectivity ....................................................25 -

The Case for Mandatory Separation of Chairperson and Ceo Roles in India

INDIA INSIGHTS THE CASE FOR MANDATORY SEPARATION OF CHAIRPERSON AND CEO ROLES IN INDIA Results of a Membership Survey Conducted by CFA Institute in Partnership with CFA Society India Sivananth Ramachandran, CFA June 2020 THE CASE FOR MANDATORY SEPARATION OF CHAIRPERSON AND CEO ROLES IN INDIA The mission of CFA Institute is to lead the investment profession globally by promoting the highest standards of ethics, education, and professional excellence for the ultimate benefit of society. CFA Institute, with more than 170,000 members worldwide, is the not-for-profit organization that awards the Chartered Financial Analyst® (CFA) and Certifi- cate in Investment Performance Measurement® (CIPM) designations. CFA®, Chartered Financial Analyst®, AIMR-PPS®, and GIPS® are just a few of the trademarks owned by CFA Institute. To view a list of CFA Institute trademarks and the Guide for the Use of CFA Institute Marks, please visit our website at www.cfainstitute.org. © 2020 CFA Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. Contents Acknowledgments v Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 Separation of Chairperson and CEO Roles in the Indian Context 4 Survey Methodology and Highlights 6 Separation of Chairperson and CEO Roles 6 Independent Directors 9 Conclusion 11 Appendix I – Profile of Survey Correspondents 12 © 2020 CFA INSTITUTE. -

Business Education Financial Training Monday June 22 2015 | @Ftreports Schools Adapt to Changing Times Inside

FT SPECIAL REPORT Business Education Financial Training Monday June 22 2015 www.ft.com/reports | @ftreports Schools adapt to changing times Inside There is now a greater risenslightlysince2008,butopportuni- tiesforhisgraduatestofindtradingjobs emphasis on risk have diminished. Many students want management and ethics, toworkincompliance,headds. The Global Masters in “Theneedforregulationandriskcon- Finance programmes writes Jonathan Moules trolhasdramaticallyincreasedafterthe The rankings of the best 2008 banking crisis,”he says. “Recently one of our students obtained a perma- courses in the world heeffectsofthe2008finan- nent position at Banque de France, Page 2 cial crisis continue to rever- which is currently investing signifi- berate around the world’s cantlyinitsriskdepartment.” financial centres. In New The job skills required, Prof Quittard- Follow the money T York, regulators warn of Pinon adds, are a good knowledge of further fines for the rigging of foreign mathematical tools and IT techniques How much more exchange markets following a $5.6bn andakeengraspofglobalfinancialmar- could you earn on settlementthisMayandindividualsstill kets. “Many of our students come to completion of a Masters face court for alleged personal misde- improve these skills and those with meanours. working experience are convinced of in Finance degree? Financial training has had to adapt to thisnecessity.” Page 5 thisworld,notleastbygreateremphasis JacquesOlivier,whorunstheMiFpro- on risk management and updating its gramme and is joint-programme direc- Striking out alone regulations curriculum in line with rule tor of the MBA-MSc international changes. Courses on ethics have gained finance dual degree at HEC Paris, notes Mutaz Qubbaj on why anewdegreeofimportance. that while demand post-2008 for sales he chose to become In a variety of ways, financial training and trading roles has fallen, interest in an entrepreneur is moving on from the crisis. -

Computer-Based Testing

Computer-Based Testing Test Center Locations by Country/Region The following list of planned test center locations is subject to change based on availability and demand. Test center options with confirmed available seating will be presented to you during the scheduling process. Argentina Buenos Aires Armenia Yerevan Australia Brisbane Melbourne Perth Sydney Austria Vienna Azerbaijan Baku Bahamas Nassau Bahrain Manama Bangladesh Dhaka Barbados Bridgetown Belgium Brussels Bermuda Hamilton Bolivia La Paz Botswana Gaborone Brazil Belo Horizonte Brasilia Curitiba Recife Rio de Janeiro Sao Paulo Brunei Darussalam Brunei Bulgaria Sofia Cambodia Phnom Penh Canada Calgary, AB Edmonton, AB Halifax, NS Hamilton, ON London, ON Mississauga, ON Montreal, QC Ottawa, ON Quebec City, QC Regina, SK Saskatoon, SK St. John’s, NL Toronto, ON Vancouver, BC Victoria, BC Winnipeg, MB Cayman Islands Grand Cayman Chile Santiago China (Mainland) Beijing Chang Sha Chengdu Chongqing Dalian Guangzhou Hangzhou Harbin Huzhou Jinan Kunming Macao Nanjing Qingdao Shanghai Shenzhen Tianjin Wuhan Xi’an Colombia Cali Bogota Costa Rica San Jose Croatia Zagreb Cyprus Nicosia Czech Republic Prague Denmark Copenhagen Dominican Republic Santo Domingo Egypt Cairo Finland Helsinki France Marseille Paris Germany Berlin Frankfurt Hamburg Munich Ghana Accra Greece Athens Thessaloniki Guatemala Guatemala City Hong Kong SAR, China Hong Kong Hungary Budapest Iceland Reykjavik India Ahmedabad Bengaluru Bhopal Chennai Gandhinagar Hyderabad Indore Jaipur Kolkata Lucknow Mumbai Navi Mumbai -

Fintech 2018: the Asia Pacific Edition

FINTECH 2018 THE ASIA PACIFIC EDITION ©2018 CFA Institute. All rights reserved. 1 FINTECH 2018 THE ASIA PACIFIC EDITION © 2018 CFA Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission of the copyright holder. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to: Copyright Permissions, CFA Institute, 915 East High Street, Charlottesville, Virginia 22902. CFA®, Chartered Financial Analyst®, CIPM®, Investment Foundations™, and GIPS® are just a few of the trademarks owned by CFA Institute. To view a list of CFA Institute trademarks and the Guide for the Use of CFA Institute Marks, please visit our website at www.cfainstitute.org. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is provided with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. September 2018 What will be the most interesting trends on Fintech going forward? This Fintech report provides insight, analysis and identifies trends on developments in blockchain, artificial intelligence and more. It is a comprehensive study designed to inform people in the industry about upcoming trends, and help them better understand and manage the issues, opportunities, and challenges ahead. Nick Pollard, Managing Director, Asia Pacific, CFA Institute Acknowledgement In addition to the experts who contributed to this volume and spoke at our events, many colleagues at CFA Institute on both sides of the Pacific have worked tirelessly to make this happen. -

Research Challenge Uk Final & Careers Panel

RESEARCH CHALLENGE UK FINAL & CAREERS PANEL 15 MARCH 2018 CFA Society of the UK 4th Floor, Minster House 42 Mincing Lane London EC3R 7AE [email protected] RUNNING ORDER 17:00 Welcome and Introduction from Bank of America Merrill Lynch Simon L Greenwell Head of Research, Bank of America Merrill Lynch 17:05 Welcome from CFA UK Will Goodhart CEO, CFA UK 17:10 Reading of the rules Nick Bartlett, CFA, Director of Education, CFA UK 17:15 Team presentations and Q&A 18:40 Refreshment break 19:00 Importance of networking, soft skills and building resilience in a competitive industry Steve Rook Author and Careers Advisor 19:30 Career challenges faced in equity analysis Mark Manduca, CFA, Managing Director and Equity Research Analyst, Bank of America Merill Lynch 20:00 Announcement of the winners and closing comments James Dolman, CFA, Judging Panel Chair 20:15 Drinks reception CFA UK RESEARCH CHALLENGE & CAREERS PANEL 2018 | 3 WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO... Bank of America Merrill Lynch Lee Harmsworth Robyn Dawson Daniel Giamouridis Muriel Piednoel CFA Society of the UK Will Goodhart Nick Bartlett, CFA Priya Ramsden Fiona Edwards Anna Pinch Nicki Morris Felicity Smith Michael Jackson Hema Patel CFA Institute Steve Wallace, MCSI, CAIA Graders Dr. James Seaton Janice Dorish, CFA Judges Panel Ade Roberts, CFA James Dolman, CFA Greg Collett, CFA Orlaith O’Connor, CFA 4 | CFA UK RESEARCH CHALLENGE & CAREERS PANEL 2018 ABOUT THE GLOBAL INVESTMENT RESEARCH CHALLENGE UK FINAL Welcome to the UK Final of the Global Research Challenge, hosted by the CFA Society of the UK. This is the tenth year the UK has hosted a local Challenge, and we are very grateful for the support of all those involved. -

Computer-Based Testing Test Center Locations the Following List of Planned Test Center Locations Is Subject to Change Based on Availability and Demand

Computer-Based Testing Test Center Locations The following list of planned test center locations is subject to change based on availability and demand. Test center options with confirmed available seating will be presented to you during the scheduling process. ARGENTINA Buenos Aires ARMENIA YEREVAN AUSTRALIA Brisbane Crawley WA Melbourne PERTH Sydney Ultimo AUSTRIA Vienna Azerbaijan Baku Bahamas Nassau BAHRAIN Manama BANGLADESH DHAKA Barbados Bridgetown Belgium BRUSSELS Bermuda Paget BOLIVIA La Paz BRAZIL Belo Horizonte Brasilia Curitiba Recife Rio de Janeiro Sao Paulo Brunei Darussalam Bandar Seri Begawan Brunei BULGARIA SOFIA Cambodia Phnom Penh CANADA Calgary, AB Dartmouth Edmonton Halifax Hamilton LONDON Mississauga Montréal Ottawa Pointe-Claire Quebec City Regina Saskatoon Scarborough St. John's Toronto Vancouver Victoria Winnipeg Cayman Islands Grand Cayman CHILE Las Condes CHINA (Mainland) BEIJING CHANGSHA Chengdu Chongqing Dalian Guangdong Guangzhou HANGZHOU JINAN KUNMING Liaoning NANJING Qingdao SHANGHAI SHENYANG Shenzhen Tianjin WUHAN XI'AN COLOMBIA CALI CHIA COSTA RICA SAN JOSE CROATIA Zagreb CYPRUS NICOSIA CZECH REPUBLIC Prague DENMARK COPENHAGEN DEU Frankfurt DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Santo Domingo EGYPT Cairo FINLAND Helsinki FRANCE MARSEILLE PARIS GERMANY Berlin Frankfurt Hamburg Munich GHANA Accra GREECE Athens Thessaloniki GUAM Dededo GUATEMALA Guatemala City HONG KONG SAR, China Hong Kong KOWLOON Kwai Chung Tsuen Wan NT Tuen Mun, NT HUNGARY BUDAPEST Iceland Reykjavik INDIA BEIJING Bengaluru Bhopal Chennai Gandhinagar Hyderabad -

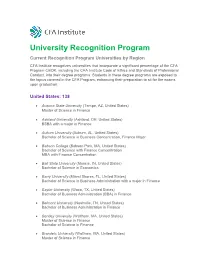

University Recognition Program

University Recognition Program Current Recognition Program Universities by Region CFA Institute recognizes universities that incorporate a significant percentage of the CFA Program CBOK, including the CFA Institute Code of Ethics and Standards of Professional Conduct, into their degree programs. Students in these degree programs are exposed to the topics covered in the CFA Program, enhancing their preparation to sit for the exams upon graduation. United States: 138 Arizona State University (Tempe, AZ, United States) Master of Science in Finance Ashland University (Ashland, OH, United States) BSBA with a major in Finance Auburn University (Auburn, AL, United States) Bachelor of Science in Business Concentration, Finance Major Babson College (Babson Park, MA, United States) Bachelor of Science with Finance Concentration MBA with Finance Concentration Ball State University (Muncie, IN, United States) Bachelor of Science in Economics Barry University (Miami Shores, FL, United States) Bachelor of Science in Business Administration with a major in Finance Baylor University (Waco, TX, United States) Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) in Finance Belmont University (Nashville, TN, United States) Bachelor of Business Administration in Finance Bentley University (Waltham, MA, United States) Master of Science in Finance Bachelor of Science in Finance Brandeis University (Waltham, MA, United States) Master of Science in Finance Brigham Young University (Provo, UT, United States) Bachelor of Science in Finance MBA Butler University -

Historical Curiosities of Wall Street: a Brief Guide

the summary suspension automatically became a CENSURE Effective 7 March 2017, Ronald L. Strauss (Chicago), Revocation on 7 December 2016. Effective 2 March 2017, CFA Institute imposed a Cen- a lapsed charterholder member, permanently On 26 May 2016, in a federal court hearing in sure on Kefei Wang (Beijing, China), a charterholder resigned his membership in CFA Institute and any New York City, Parietti admitted that between 2006 member. CFA Institute found that Wang violated the member society during the course of a Professional and 2008, while employed as a trader with Deutsche CFA Institute Code of Ethics and Standards of Profes- Conduct investigation regarding findings made by Bank US Financial Markets, he participated in a sional Conduct: I(A) – Knowledge of the Law (2014). the SEC that from 2009 until 2011 he dedicated insuf- scheme to manipulate the London Interbank Offered The US Congress created the Immigrant Investor ficient resources to compliance, which contributed Rate (LIBOR). He pleaded guilty to felony charges of Program, also known as the “EB-5 Program,” to to multiple compliance failures at the investment conspiring to commit wire fraud and bank fraud. stimulate the economy through job creation and advisory firm where he served as president until his retirement in 2014. On 30 January 2017, CFA Institute imposed a Summary capital investment by foreign investors. EB-5 invest- Suspension on Gordon D. Brooks (Cathedral City, ments are typically offered as limited partnership Effective 13 March 2017, David E. West (Homer Glen, California), a charterholder member, automatically interests. From January 2010 through May 2014, Illinois), a lapsed charterholder member, perma- suspending his membership and right to use the Wang received $40,000, which constituted his nently resigned his right to reactivate his member- CFA designation.