Master's Degree Programme – Second Cycle (DM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programmagasin 2005

15. oslO INTERNASJONALE FILMFESTIVal 17.-27. november 2005 VELKOMMEN TIL 15. OSLO INTERNASJONALE FILMFESTIVAL 17.-27 NOVEMBER 2005 Velkommen til ny runde med filmfestdager i Oslo. På nytt kan vi tilby et fantastisk program med aktuelle og spennende filmer. Som tidligere vil vi underholde, forarge, skremme og utfordre. Sjekk det beste vi har funnet via godt samarbeid med norske filmimportører. Opplev også filmer som du kanskje aldri seinere får se i Norge. En haug med internasjonale prisvinnere fra Sundance, Berlin, Cannes, Venezia med flere. Vi åpner med en nordisk premiere av George Clooneys filmregi nr. 2: Good Night, and Good Luck. Om legendariske nyhetsjournalister på 50-tallet som ikke vek unna for fokus på rasisme og maktmisbruk. Og hvordan misbruk av frykt som våpen da som nå er en trussel for ethvert demokrati. Kritikerpris, pluss beste manus og skuespiller i Venezia. Åpningsfilm i New York, avslutning i London. Japansk film er på sitt beste i Canary med et gripende portrett av barns verden. Støymusikk lanseres som effektivt middel mot virustrusler i Eli, Eli,..Ny fantasiferd innen japapansk animé med Mind Game. Nordisk festivalpremiere i spesialvisning: Walk the Line, sterkt og vakkert. Suverent tolker Joaquin Phoenix og Reese Witherspoon våre helter Johnny Cash og June Carter. Mer musikk blir det i dypt personlige og inspirerende portretter av unike musikere og kulthelter som Townes Van Zandt, Roky Erickson (regibesøk) og Billy Childish. Og all slags metal får sitt kart og sin fanbegeistrede hyllest i Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey. Fantasifullt, absurd og/eller sprøtt blir møtet med Mirrormask, Bangkok Loco, The District! og Night Watch. -

10,1 MB | 252 S

Sekans Sinema Kültürü Dergisi Aralık 2018, Sayı e9, Ankara © Sekans Sinema Grubu Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Sekans Sinema Kültürü Dergisi ve sekans.org içeriği, Sekans Sinema Grubu ve yazarlardan izin alınmaksızın kullanılamaz. [email protected] http://www.sekans.org Yayın Yönetmeni Ender Bazen Dosya Editörü A. Kadir Güneytepe Kapak Düzenleme ve Tasarım Cem Kayalıgil [email protected] Tansu Ayşe Fıçıcılar [email protected] Web Uygulama Ayhan Yılmaz [email protected] Kapak Fotoğrafı Güz Sonatı (Höstsonaten, Ingmar Bergman, 1978) Katkıda Bulunanlar Natig Ahmedli, Ahmet Akalın, Nurten Bayraktar, Gülizar Çelik, Gizem Çınar, M. Baki Demirtaş, Ekin Eren, Aleksey Fedorchenko, Ulaş Başar Gezgin, Erman Görgü, Dilan İlhan, Erdem İlic, Süheyla Tolunay İşlek, Erbolot Kasymov, Sertaç Koyuncu, Dila Naz Madenoğlu, İlker Mutlu, Yalçın Savuran, Mine Tezgiden, Seda Usubütün, Rukhsora Yusupova Bu elektronik dergi, bir Sekans Sinema Grubu ürünüdür. ÖNSÖZ Bir derginin en iyi yanı bir sayı içerisindeki birçok farklı başlığın sinemanın zengin dünyası içinde sinemanın bambaşka alanlarına sıçramayı sağlayabiliyor olması galiba. Her yeni sayıda yazarlarımızın ilgi alanlarının katkısıyla bu zengin dünyadaki her araştırma, her keşif bir diğer okumayı da besliyor çoğu zaman. Her sayıda olduğu gibi Sekans Sinema Kültürü Dergisi e-9’da da bu amaçla çalışmalara başlanmış, içeriğin ana hatları belirlenmişti. Sinemamızdan ve dünya sinemasından incelemeler, bir yönetmen söyleşisi, belgesel, akım, tür, anısına gibi bölümler, 50 yaşında bir film, bir ülke sinemasını ele alan dosya ile bu sayıda da farklı coğrafyalara, tarihlere, yönetmenlere, ülkelere ve düşüncelere yolculuk etmek için yola çıkılmıştı. Tüm bu çalışmaları okuyucuya ulaştırmanın yoğun çabası içindeyken sinema dünyasından kötü bir haber geldi. İtalyan yönetmen Bernardo Bertolucci, çokça tartışılmış, üzerine defalarca yazılmış, çizilmiş filmlerini ardında bırakarak bu dünyaya gözlerini kapamıştı. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan SOCIAL CRITICISM in the ENGLISH NOVEL

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-8810 CLEMENTS, Frances Marion, 1927- SOCIAL CRITICISM IN THE ENGLISH NOVEL: 1740-1754. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan SOCIAL CRITICISM IN THE ENGLISH NOVEL 1740- 175^ DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Frances Marion Clements, B.A., M.A. * # * * # * The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by (L_Lji.b A< i W L _ Adviser Department of English ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the Library of Congress and the Folger Shakespeare Library for allowing me to use their resources. I also owe a large debt to the Newberry Library, the State Library of Ohio and the university libraries of Yale, Miami of Ohio, Ohio Wesleyan, Chicago, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Wisconsin for their generosity in lending books. Their willingness to entrust precious eighteenth-century volumes to the postal service greatly facilitated my research. My largest debt, however, is to my adviser, Professor Richard D. Altick, who placed his extensive knowledge of British social history and of the British novel at my disposal, and who patiently read my manuscript more times than either of us likes to remember. Both his criticism and his praise were indispensable. VITA October 17, 1927 Born - Lynchburg, Virginia 1950 .......... A. B., Randolph-Macon Women's College, Lynchburg, Virginia 1950-1959• • • • United States Foreign Service 1962-1967. • • • Teaching Assistant, Department of English, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1962 ..... -

English and Armenian Languages

FOUNDATION FOR CIVIL AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Authors and Editors Samvel Mkhitaryan Chairman of the Foundation, Project initiator and Guidebook Editor in Chief Working and expert group Mkrtich Anushyan Roman Melikyan Armen Grigoryan Marine Papyan Karine Mkhitaryan Ruben Gasparyan Sonia Hakobyan Sevak Hakobyan Ashot Mirzoyan Tamar Azarbaryan Taguhi Khachatryan Naira Aharonyan POLITICAL PARTIES OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA PARTICIPATING IN THE NATIONAL ASSASSEEEEMBLYMBLY ELECTIONS 2012 UNDER PROPORTIONAL SYSTEM VOTER’S GUIDEGUIDEBOOKBOOK 2012 YEREVAN “POLITICAL PARTIES OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA PARTICIPATING IN THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS 2012 UNDER PROPORTIONAL SYSTEM” VOTER’S GUIDEBOOK -Yerevan “““FOUNDATION“FOUNDATION FOR CIVIL AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENTDEVELOPMENT””””,,,, YYYEREVYEREVEREVANANANAN,, 2012 ––– 111321323232 pagespages.... Authors and Editors Samvel Mkhitaryan,, Mkrtich Anushyan,, Roman Melikyan, Armen Grigoryan, Marine Papyan, Karine Mkhitaryan, Ruben Gasparyan, Sonia Hakobyan, Sevak Hakobyan, Ashot Mirzoyan, Tamar Azarbaryan, Taguhi Khachatryan, Naira Aharonyan This Voter’s Guidebook presents brief, unbiased, comparative information on activities, objectives, goals and program fundamentals of political parties participating in RA National Assembly elections 2012 under proportional system. This Guidebook is developed on the basis of responses as provided by political parties in the questionnaire developed within the scope of the grant project ''Political Parties of the Republic of Armenia Directory and Voter's Guidebook'' -

Gary Essert Filmex Files, 1966-1981

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9v19q8dc No online items Finding Aid for the Gary Essert Filmex Files, 1966-1981 Processed by Performing Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by N. Vega and J. Graham UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Gary Essert 270 1 Filmex Files, 1966-1981 Descriptive Summary Title: Gary Essert Filmex Files Date (inclusive): 1966-1981 Collection number: 270 Creator: Essert, Gary Extent: 39 boxes (19.25 linear ft.) Abstract: Gary Essert and with the assistance of George Cukor, launched the first Los Angeles International Film Exposition (Filmex) in Hollywood, CA (1971). The collection consists of documents and photographs relating to films shown at the Los Angeles International Film Exposition(Filmex). Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Advance notice required for access. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Sexology, Psychoanalysis, Literature

LANG, DAMOUSI & LEWIS BIRGIT LANG, JOY DAMOUSI AND Birgit Lang is Starting with Central Europe and concluding with the AlISON LEWIS Associate Professor United States of America, A history of the case study tells of German at the story of the genre as inseparable from the foundation The University of Melbourne of sexology and psychoanalysis and integral to the history of European literature. It examines the nineteenth- and Joy Damousi is twentieth-century pioneers of the case study who sought ARC Kathleen answers to the mysteries of sexual identity and shaped Fitzpatrick Laureate the way we think about sexual modernity. These pioneers Fellow and Professor of History at include members of professional elites (psychiatrists, A history of study of case the A history A history of The University psychoanalysts and jurists) and creative writers, writing of Melbourne for newly emerging sexual publics. Alison Lewis Where previous accounts of the case study have is Professor of German at approached the history of the genre from a single The University disciplinary perspective, this book stands out for its the case study of Melbourne interdisciplinary approach, well-suited to negotiating the ambivalent contexts of modernity. It focuses on key Sexology, psychoanalysis, literature formative moments and locations in the genre’s past COVER Schad, Christian where the conventions of the case study were contested (1894–1982): Portrait as part of a more profound enquiry into the nature of the literature psychoanalysis, Sexology, of Dr Haustein, 1928. Madrid, Museo human subject. Thyssen-Bornemisza. Oil on canvas, 80.5 x 55 cm. Dimension with frame: Among the figures considered in this volume are 97 x 72 x 5 cm. -

New Nordic Films Catalogue 2010

18-21 AUGUST 201 0 NEW NORDIC FILMS Welcome to Haugesund WE ARE PLEASED to state that the Nordic coun - International Film Festival an important meeting N O I tries have made Haugesund an important meeting place also for Europe’s producers. For this reason T C place for the international film industry. we have established the Nordic Co-Production U D O Forum as a part of New Nordic Films. R T To achieve our objective of becoming one of the N I leading film festivals for Nordic cinema, we still Support from Innovation Norway has also made it work together with the Gothenburg Film Festival, possible to develop a location programme together which each year hosts the Nordic Film with Film Commission Norway. Market in February. We strongly wish to play an important part in the In this connection, we would like to take the oppor - Nordic and European film industry, and I am tunity to thank the Nordic Film & TV Fund and the delight ed that so many professionals from abroad Nordic Council of Ministers for their annual contri - have decided to visit Haugesund. bution to both Gothenburg and Haugesund. We also thank the Film Institutes of the Nordic Countries for their cooperation and advice. This year we have also received important and highly appreciated support from the MEDIA Programme in Brüssels. As a member of FIAPF (the International Fede - ration of Film Producing Associations), the Norwegian International Film Festival thinks it is Gunnar Johan Løvvik natural to make Norway and the Norwegian Festival Director 2 Contents 2 Welcome to Haugesund 4 Day by day 6 City Map Haugesund 7 Welcome to the 2010 New Nordic Films -THE NORWEGIAN INTERNATIONAL 8 Co-produce – or die? FILM FESTIVAL is owned by 9 Case Study: Babycall FILM & KINO, The Municipality of 10 Final Cut / Canadian Landscape Haugesund and Rogaland County. -

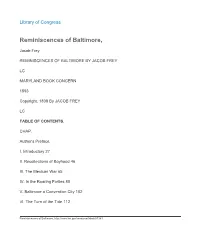

Reminiscences of Baltimore,: a Machine

Library of Congress Reminiscences of Baltimore, Jacob Frey REMINISCENCES OF BALTIMORE BY JACOB FREY LC MARYLAND BOOK CONCERN 1893 Copyright, 1808 By JACOB FREY LC TABLE OF CONTENTS. CHAP. Author's Preface. I. Introductory 27 II. Recollections of Boyhood 46 III. The Mexican War 65 IV. In the Roaring Forties 80 V. Baltimore a Convention City 102 VI. The Turn of the Tide 112 Reminiscences of Baltimore, http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.01361 Library of Congress VII. The War Cloud 125 VIII. After the Storm 139 IX. Charity and Reorganization 146 X. The Constitution of '64 and '67 162 XI. Commotions and Alarms 177 XII. Grove, the Photographer 197 XIII. Baltimore's Military Defenders 211 XIV. Banking Extraordinary 221 XV. “ “ Continued 235 XVI. The Sequence of a Crime 252 XVII. The Wharton-Ketchum Case and Others 266 XVIII. A Chapter of Chat 280 XIX. The Story of a Reformation 293 XX. The Story of Emily Brown 301 XXI. In Recent Years 311 XXII. The Marshal's Office 320 XXIII. The Press of Baltimore 332 Reminiscences of Baltimore, http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.01361 Library of Congress XXIV. The Stage in Baltimore 346 XXV. Educational Institutions and Public Works 364 XXVI. Baltimore Markets 389 XXVII. The Harbor of Baltimore 402 XXVIII. Industrial Baltimore 417 XXIX. Street Railways and Their Relation to Urban Development 434 XXX. Busy Men and Fair Women 443 XXXI. Public and Recent Buildings 456 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. Portrait of Jacob Frey Frontispiece Pratt Street Opposite Page, 30 Washington Monument “ “ 41 Charles Street at Franklin—Looking North “ “ 52 Portrait of C. -

Australian Essays

Australian Essays Adams, Francis W. L. (1862-1893) University of Sydney Library Sydney, Australia 2003 http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/setis/id/adaessa © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by William Inglis & Co. Melbourne 1886. 167pp. All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1886 setis australian etexts criticism essays 1870-1889 Australian Essays Melbourne William Inglis & Co. 1886 To Matthew Arnold in England. ‘Master, with this I send you, as a boy that watches from below some cross-bow bird swoop on his quarry carried up aloft, and cries a cry of victory to his flight with sheer joy of achievement—So to you I send my voice across the sundering sea, weak, lost within the winds and surfy waves, but with all glad acknowledgment fulfilled and honour to you and to sovran Truth!’ January, 1886. Contents. PAGE. PREFACE ix. MELBOURNE AND HER CIVILIZATION I THE POETRY OF ADAM LINDSAY GORDON II THE SALVATION ARMY 27 SYDNEY AND HER CIVILIZATION 50 CULTURE 73 “DAWNWARDS,” A DIALOGUE INTRODUCTION 90 I. 97 II. 105 III. 114 IV. 122 V. 138 VI. 146 Preface. IT would be absurd to suppose that it will not seem clear, to whatever readers this little book may find here, that one of the principal characters of the Dialogue is a man for whom we all, I think, feel more interest, admiration, and respect than any other among us. That this is so in reality, I must beg to deny, and I hope that, when I state that I neither have myself, nor know anyone who has, the honour of his acquaintance—nay, that I have never even seen him—I hope that I shall stand acquitted of all charges of personality. -

© 2011 Kathleen Sclafani ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2011 Kathleen Sclafani ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ‘BORDER CONSCIOUSNESS’ AND THE RE‐IMAGINATION OF NATION IN THE FILMS OF AKIN, DRESEN AND PETZOLD by KATHLEEN J. SCLAFANI A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School‐New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Comparative Literature written under the direction of Fatima Naqvi and approved by _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey JANUARY 2011 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ‘Border Consciousness’ and the Re‐imagination of Nation in the Films of Akin, Dresen and Petzold By KATHLEEN J. SCLAFANI Dissertation Director: Fatima Naqvi In my dissertation I explore the role that borders play in the construction of German identity through the films of Fatih Akin, Andreas Dresen and Christian Petzold. Despite the insistence of conservatives that Germany is not an “immigration country,” I argue that the historical fluctuation of borders and the movement of populations into and out of Germany have resulted in a heightened awareness of borders and their significance that contributes to a sense of ambivalence about national identity. This heightened awareness can be seen as a type of “border consciousness,” a term that originated in Chicano/a studies and has been used to analyze exilic and diasporic cinema but which I reconsider in the context of German film. By examining tropes of borders and border crossings, as well as representations of liminality in the work of German filmmakers from various backgrounds, I argue that in these works, border consciousness can be seen as a function of a relationship to national boundaries rooted in histories of displacement, but not necessarily limited to the experiences of migrants and minorities. -

Volume 13 2012 Volume 13 2012 a Magazine of Creative Expression by Students, Faculty, and Staff at Southeast Community College

Volume 13 2012 Volume 13 Volume 2012 A magazine of creative expression by students, faculty, and staff at Southeast Community College Volume 13 2012 “In art as in love, instinct is enough.” Anatole France 1 C REATIVITY LIVES HERE. 2009 Cameron Koll, “Baby Girl” Winner of the CCHA Merit Award in Fiction 2010 Illuminations 3rd place winner of Best Literary Magazine, CCHA, Central Division 2011 Katrina Bennett, “Brown Walls” Winner of the CCHA 1st place Non-Fiction Award 2011 Illuminations 1st place winner of Best Literary Magazine, CCHA, Central Division Front cover image, “Color Whirl,” by Deborah Hull and back cover image, “Feeling at Home,” by Emilio Franso 2 I LLUMINATIONS VOLUME 13 Editor: Kimberly Fangman Editorial Team: Debrenee Adkisson, Teresa Bissegger, Jennifer Creller, Kara Gall, Trevor Geary, Anna Loden, Elliot Newbold, Danul Patterson, James Redd, Mary Ann Rowe, Kathy Samuelson, Natalie Schwarz, Susan M. Th aler, Sarah Trainin Graphic Designer: Kristine Meek Project Assistants: Cathy Barringer, Rebecca Burt, Dan Everhart, Sue Fielder, Nancy Hagler-Vujovic, Kate Loden, Rachel Mason, Donna Osterhoudt, Merrill Peterson, Janalee Petsch, Carolee Ritter, Amy Rockel, Richard Ross, Kathy Samuelson, Laura Th ompson, Barb Tracy, Bang Tran, Pat Underwood, the English instructors of the Arts and Sciences Division Conceptual Creator: Shane Zephier Illuminations publishes creative prose, poetry, and visual art, as well as academic and literary writing. We encourage submissions from across the disciplines. Our mission is to feature outstanding artistic works with a diversity of voices, styles, and subjects meaningful to the SCC community. Illuminations is further evidence that critical thinking and creative expression are valued at Southeast Community College. -

Centaur Liniments. Children

. «S WHOLE NUMBER 1583. NORWALK, CONNECTICUT, TUESDAY, MAY 7, 1878. YOL. LXI.--NUMBER 19 Bo it enacted by the Senate and nouse of lepr«- The Mother's Lesson. mons anil I fought Mr. Brown energetically ner, which shall be as valid as if recorded by EQUIPMENT. snntntivesin General Assembly convened. NORWALK GAZETTE, • .' Harouu AI Kascliid. REALESTATE. but in vain. The last words he uttered as lie the judgment creditor himself. Number of locomotives (not in-' No lease of any railroad h.-ieafter made BT SALVIA DALE. One day, Haroun Al Kaschid read Sec. 4. Nothing in this act contained shall eluding switching engines). shall be'binding on either of t'ia contracting PUBLISHED EVEBHUiSDAY MOBIIRQ. left the room were, "Depend upon it, Miss Average weight of same includ A book wherein the poet said: lie construed toauthorize any such lien to hold parties for a period of iro n than twilve To Rent. "A story, a story, dear mother," Abigail, I'm right. I seldom make a mistake and be valid as to any real estate, or any in ing lender, water, and fuel. months unless the same shall bj approved by Tlie Seeomt Oldest Paper In tlie State. Centaur Entreated the soft, tender voice, Number of switching engines. •' Where are the kings, and where the rest about such things, and I am certain that Mr. terest therein, which might not have been the stockholders of the ccmpany or com The First Floor of a Dwelling House, with levied upon under an execution On the same Number of passenger cars.