Antelopes: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arabian Ungulate CAMP & Leopard, Tahr, and Oryx PHVA Final Report 2001.Pdf

Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) For The Arabian Ungulates and Leopard & Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) For the Arabian Leopard, Tahr, and Arabian Oryx 1 © Copyright 2001 by CBSG. A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN). 2001. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for the Arabian Leopard and Arabian Ungulates with Population and Habitat Viability Assessments for the Arabian Leopard, Arabian Oryx, and Tahr Reports. CBSG, Apple Valley, MN. USA. Additional copies of Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for the Arabian Leopard and Arabian Ungulates with Population and Habitat Viability Assessments for the Arabian Leopard, Arabian Oryx, and Tahr Reports can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. USA. 2 Donor 3 4 Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) For The Arabian Ungulates and Leopard & Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) For the Arabian Leopard, Tahr, and Arabian Oryx TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: Executive Summary 5. SECTION 2: Arabian Gazelles Reports 18. SECTION 3: Tahr and Ibex Reports 28. SECTION 4: Arabian Oryx Reports 41. SECTION 5: Arabian Leopard Reports 56. SECTION 6: New IUCN Red List Categories & Criteria; Taxon Data Sheet; and CBSG Workshop Process. 66. SECTION 7: List of Participants 116. 5 6 Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) For The Arabian Ungulates and Leopard & Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) For the Arabian Leopard, Tahr, and Arabian Oryx SECTION 1 Executive Summary 7 8 Executive Summary The ungulates of the Arabian peninsula region - Arabian Oryx, Arabian tahr, ibex, and the gazelles - generally are poorly known among local communities and the general public. -

Boselaphus Tragocamelus</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey 2008 Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae) David M. Leslie Jr. U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Leslie, David M. Jr., "Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae)" (2008). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 723. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/723 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MAMMALIAN SPECIES 813:1–16 Boselaphus tragocamelus (Artiodactyla: Bovidae) DAVID M. LESLIE,JR. United States Geological Survey, Oklahoma Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078-3051, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Boselaphus tragocamelus (Pallas, 1766) is a bovid commonly called the nilgai or blue bull and is Asia’s largest antelope. A sexually dimorphic ungulate of large stature and unique coloration, it is the only species in the genus Boselaphus. It is endemic to peninsular India and small parts of Pakistan and Nepal, has been extirpated from Bangladesh, and has been introduced in the United States (Texas), Mexico, South Africa, and Italy. It prefers open grassland and savannas and locally is a significant agricultural pest in India. It is not of special conservation concern and is well represented in zoos and private collections throughout the world. DOI: 10.1644/813.1. -

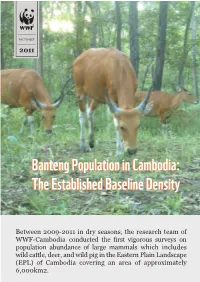

Bantengbanteng Populationpopulation Inin Cambodia:Cambodia: Thethe Establishedestablished Baselinebaseline Densitydensity © FA / WWF-Cambodia

FACTSHEET 2011 BantengBanteng PopulationPopulation inin Cambodia:Cambodia: TheThe EstablishedEstablished BaselineBaseline DensityDensity © FA / WWF-Cambodia Between 2009-2011 in dry seasons, the research team of WWF-Cambodia conducted the first vigorous surveys on population abundance of large mammals which includes wild cattle, deer, and wild pig in the Eastern Plain Landscape (EPL) of Cambodia covering an area of approximately 6,000km2. Banteng: Globally Endangered Species Banteng (bos javanicus) is a species of wild cattle that historically inhabited deciduous and semi- evergreen forests from Northeast India and Southern Yunnan through mainland Southeast Asia and Peninsular Malaysia to Borneo and Java. Since 1996, banteng has been listed by IUCN as globally endangered on the basis of an inferred decline over the last 30 years of more than 50%. Banteng is most likely the ancestor of Southeast Asia’s domestic cattle and it is considered to be one of the most beautiful and graceful of all wild cattle species. In Cambodia, banteng populations have decreased dramatically since the late 1960s. Poaching to sell the meat and horns as trophies constitutes a major threat to remnant populations even though banteng is legally protected. © FA / WWF-Cambodia Monitoring Banteng Population in the Landscape Knowledge of animal populations is central to understanding their status and to planning their management and conservation. That is why WWF has several research projects in the EPL to gain more information about the biodiversity values of PPWS and MPF. Regular line transect surveys are conducted to collect data on large ungulates like banteng, gaur, and Eld’s deer--all potential prey species for large carnivores including tigers. -

Projet De Motion Sur La Dégradation De

WCC-2012-Res-023-EN Support for national and regional initiatives for the conservation of large mammals in the Sahara RECOGNIZING IUCN’s mission, since its creation, to promote the conservation of biodiversity; AWARE that desert ecosystems and their biodiversity are particularly vulnerable to natural and anthropogenic climate change; RECOGNIZING that the Sahara is very rich in biodiversity, which is often underestimated and is potentially important in the provision of ecosystem services and genetic resources; RECOGNIZING that the populations of large mammals have declined dramatically in desert ecosystems, and in the Sahara in particular; ALARMED that all eight species of Saharan ungulates as well as their subspecies are either threatened with extinction or already extinct, the Bubal Hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus buselaphus) is classified as Extinct, the Scimitar-horned Oryx (Oryx dammah) is Extinct in the Wild and six others are classified as Endangered or Critically Endangered; RECOGNIZING that the African Lion (Panthera leo leo) and the African Wild Dog (Lycaon pictus) have been exterminated from the Sahara and that the Northwest African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus hecki) is classified as Critically Endangered; AWARE that three of the large mammal species living in the desert require vast ranges in order to survive; NOTING that desert ecosystems have attracted very little interest or support from the global conservation community, despite covering over 17% of the world’s biomass and containing a high level of biodiversity, including -

Evaluation of 3 Milk Replacers for Hand-Rearing Indian Nilgai (Boselaphus Tragocamelus)

Evaluation of 3 Milk Replacers for Hand-Rearing Indian Nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) Catherine D. Burch, M. Diehl, and M.S Edwards Zoological Society of San Diego, San Diego Wild Animal Park, San Diego, California Hoofstock neonates are often hand-raised for multiple reasons. Feeding maternal milk is optimal, but is rarely available for hand-rearing. Therefore, suitable substitutes must be identified. Published nutrient composition of maternal milk is frequently used as a guide. In many instances, however, no information is available regarding the milk composition of a particular species. Nilgai have been successfully raised at the Wild Animal Park using several formulas. It has yet to be determined which formula(s) produce the best response. Eight nilgai (3 females, 5 males) were received for hand-rearing and were randomly assigned 1 of the following 3 formulas for a blind study: evaporated cows (EC) :nonfat cows (NFC) 2: 1, EC: Milk Matrix 30/55®:water 10: 3: 12, or EC:SPF-Iac® 2: 1. EC: NFC 2: 1, which has been used for several seasons, was designated as the control. The composition of EC:30/55:H2O 10:3: 12 is comparable to the published composition of eland milk, a species taxonomically related to nilgai. EC:SPF-Iac® 2: 1 has lipid and carbohydrate composition intermediate to the other formulas. Response parameters monitored include weight gain, stool consistency, feeding response, and overall body condition. Based on the results, Indian nilgai can be hand-reared successfully on any of the 3 milk replacers. Of the 3, however, the group fed EC:NFC 2: 1 were the heaviest at weaning and the most vigorous throughout the hand-rearing process. -

Reproductive Seasonality in Captive Wild Ruminants: Implications for Biogeographical Adaptation, Photoperiodic Control, and Life History

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 Reproductive seasonality in captive wild ruminants: implications for biogeographical adaptation, photoperiodic control, and life history Zerbe, Philipp Abstract: Zur quantitativen Beschreibung der Reproduktionsmuster wurden Daten von 110 Wildwiederkäuer- arten aus Zoos der gemässigten Zone verwendet (dabei wurde die Anzahl Tage, an denen 80% aller Geburten stattfanden, als Geburtenpeak-Breite [BPB] definiert). Diese Muster wurden mit verschiede- nen biologischen Charakteristika verknüpft und mit denen von freilebenden Tieren verglichen. Der Bre- itengrad des natürlichen Verbreitungsgebietes korreliert stark mit dem in Menschenobhut beobachteten BPB. Nur 11% der Spezies wechselten ihr reproduktives Muster zwischen Wildnis und Gefangenschaft, wobei für saisonale Spezies die errechnete Tageslichtlänge zum Zeitpunkt der Konzeption für freilebende und in Menschenobhut gehaltene Populationen gleich war. Reproduktive Saisonalität erklärt zusätzliche Varianzen im Verhältnis von Körpergewicht und Tragzeit, wobei saisonalere Spezies für ihr Körpergewicht eine kürzere Tragzeit aufweisen. Rückschliessend ist festzuhalten, dass Photoperiodik, speziell die abso- lute Tageslichtlänge, genetisch fixierter Auslöser für die Fortpflanzung ist, und dass die Plastizität der Tragzeit unterstützend auf die erfolgreiche Verbreitung der Wiederkäuer in höheren Breitengraden wirkte. A dataset on 110 wild ruminant species kept in captivity in temperate-zone zoos was used to describe their reproductive patterns quantitatively (determining the birth peak breadth BPB as the number of days in which 80% of all births occur); then this pattern was linked to various biological characteristics, and compared with free-ranging animals. Globally, latitude of natural origin highly correlates with BPB observed in captivity, with species being more seasonal originating from higher latitudes. -

Species of the Day: Banteng

Images © Brent Huffman / Ultimate Ungulate © Brent Huffman Species of the Day: Banteng The Banteng, Bos javanicus, is listed as ‘Endangered’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. A species of wild cattle, the Banteng occurs in Southeast Asia from Myanmar to Indonesia, with a large introduced population in northern Australia. The Banteng has been eradicated from much of its historical range, and the remaining wild population, estimated at no more than 8,000 individuals, is continuing to decline. Habitat loss Geographical range and hunting present the greatest threats to its survival, with the illegal trade in meat and horns www.iucnredlist.org still being widespread in Southeast Asia. www.asianwildcattle.org Help Save Species Although the Banteng is legally protected across its range and occurs in a number of www.arkive.org protected areas, the natural resources of reserves in Southeast Asia often continue to be exploited. The northern Australian population may offer a conservation alternative, although genetic studies hint that the stock may originate from domesticated Bali cattle. Fortunately, a captive population is maintained worldwide which, if managed effectively and supplemented occasionally, can provide a buffer against total extinction, and offer the potential for future re- introductions into the wild. The production of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is made possible through the IUCN Red List Partnership: Species of the Day IUCN (including the Species Survival Commission), BirdLife is sponsored by International, Conservation International, NatureServe and Zoological Society of London.. -

Al Ain Zoo – “Design & Build”

The leisure specialist Al Ain Zoo – “Design & Build” New Ideas for Plaza, UWD entrance and old part of zoo 13.02.2018 NiS 1 Al Ain Zoo EDUCATIONAL EXHIBITION This 900 hectare park near the base of Jebel Hafeet is where visitors can see a large animal collection in enclosures that closely resemble their natural habitats. At several interactive exhibits and film stations, visitors can learn about the natural habits and habitats of animals and plants. FACTS AND FIGURES Client: Al Ain Zoo Location: Al Ain, Emirate of Abu Dhabi, UAE Year: 2017 Scope: Production of signage elements, interactive exhibits and film stations OUR PERFORMANCES design - engineering - content - software – mechanics - electronics - wood – metal – 3D mold - model making – project management 2 Al Ain Zoo 3 Al Ain Zoo 4 Thank You! Al Ain Zoo – “Design & Build” New Ideas for Plaza, UWD entrance and old part of zoo 13.02.2018 NiS 5 Trillian Middle East National Insurance Building Office 504 Port Saeed, Dubai U.A.E. Tel: +971 58 833 33 39 Mail: [email protected] Imprint The booklet at hand including all of its texts, photos, drawings, and graphics, as well as the contents (concepts) presented underlie copyright protection, and are presented in strict confidence. The booklet as a whole or in part, and/ or any of the contents presented therein may not be duplicated, distributed, and/or publicly presented by a third party without prior written permission by Trillian Middle East. A license for the copyright protected right of use must be granted in order to implement or realize the concepts presented. -

Slender-Horned Gazelle Gazella Leptoceros Conservation Strategy 2020-2029

Slender-horned Gazelle Gazella leptoceros Conservation Strategy 2020-2029 Slender-horned Gazelle (Gazella leptoceros) Slender-horned Gazelle (:Conservation Strategy 2020-2029 Gazella leptoceros ) :Conservation Strategy 2020-2029 Conservation Strategy for the Slender-horned Gazelle Conservation Strategy for the Slender-horned Conservation Strategy for the Slender-horned The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of any participating organisation concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organisations. Compiled and edited by David Mallon, Violeta Barrios and Helen Senn Contributors Teresa Abaígar, Abdelkader Benkheira, Roseline Beudels-Jamar, Koen De Smet, Husam Elalqamy, Adam Eyres, Amina Fellous-Djardini, Héla Guidara-Salman, Sander Hofman, Abdelkader Jebali, Ilham Kabouya-Loucif, Maher Mahjoub, Renata Molcanova, Catherine Numa, Marie Petretto, Brigid Randle, Tim Wacher Published by IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group and Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, Edinburgh, United Kingdom Copyright ©2020 IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Recommended citation IUCN SSC ASG and RZSS. 2020. Slender-horned Gazelle (Gazella leptoceros): Conservation strategy 2020-2029. IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group and Royal Zoological Society of Scotland. -

Confirming the Pleistocene Age of the Qurta Rock

EGYPTIAN ARCHAEOLOGY Confirming the Pleistocene age of the Qurta rock art An article in EA 33 made the case for the existence of Pleistocene rock art at Qurta, c.15km north of Kom Ombo. Further fieldwork and laboratory analyses during 2008-09 have proved its pre- Holocene age as Dirk Huyge and Dimitri A G Vandenberghe discuss. The circumstances of the finding of the Qurta rock art in 2005 were described in our 2008 report in EA 33 (pp.25- 28). At Qurta, on the east bank of the Nile between Edfu and Aswan, three rock art sites have been identified: Qurta I, II and III (henceforth QI, QII and QIII). They are located in higher parts of the Nubian sandstone scarp bordering the Nile floodplain. At each site several rock art locations, panels and individual figures have been identified, with a total of at least 185 distinct images. Naturalistically drawn aurochs (Bos primigenius ) are predominant (over 75% of the total number of drawings), View of Qurta II showing the location of rock art panel QII.4.2, which is partly covered by Nubian sandstone rock debris and sediment accumulations followed by birds, hippopotami, gazelle, fish and hartebeest. In addition, some indeterminate During the 2008 field campaign, it became clear that creatures and several highly-stylized representations of rock art panel QII.4.2 was partly covered by sediment human figures appear at the sites. On the basis of the accumulations that were trapped between the engraved intrinsic characteristics of the rock art, its patination and rock face and coarse Nubian sandstone rock debris degree of weathering, as well as the archaeological and that had become separated from the scarp. -

Landscape Planning Objectives for Developing the Arid Middle East By

Landscape Planning Objectives for Developing the Arid Middle East by Safei El-Deen Harned Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fuliillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Design and Planning APPROVED: éobert H. Giles, Jr. Co·Cha.irrnan Robert G. Dyck, Co-Chairman éäéäffgWilliamL. Ochsenwald Saifur Rahman ä i éandolph May, 1988 Blacksburg, Virginia Landscape Planning Objectives for Developing the Arid Middle East by Safei El-Deen Hamed Robert H. Giles, Jr. Co-Chairman Robert G. Dyck, Co-Chairman Environmental Design and Planning (ABSTRACT) The purpose of this dissertation is to develop an approach which may aid decision-makers in the arid regions of the Middle East in formulating a comprehensive and operational set of landscape planning objectives. This purpose is sought through a dual approach; the first deals with objectives as the comerstone of the landscape planning process, and the second focuses on objectives as a signiiicant element of regional development studies. The benefits of developing landscape planning objectives are discussed, and contextual, ethical, political, social, and procedural diliiculties are examined. The relationship between setting public objectives and the rational planning process is surveyed and an iterative model of that process is suggested. Four models of setting public objcctives are compared and comprehensive criteria for evaluating these and other ones are suggested. Three existing approaches to determining landscape planning objectives are described and analyzed. The first, i.e., the Problem-Focused Approach as suggested by Lynch is applied within the context of typical problems that challenge the common land uses in the arid Middle East. -

Gazella Leptoceros

Gazella leptoceros Tassili N’Ajjer : Erg Tihodaïne. Algeria. © François Lecouat Pierre Devillers, Roseline C. Beudels-Jamar, , René-Marie Lafontaine and Jean Devillers-Terschuren Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique 71 Diagram of horns of Rhime (a) and Admi (b). Pease, 1896. The Antelopes of Eastern Algeria. Zoological Society. 72 Gazella leptoceros 1. TAXONOMY AND NOMENCLATURE 1.1. Taxonomy. Gazella leptoceros belongs to the tribe Antilopini, sub-family Antilopinae, family Bovidae, which comprises about twenty species in genera Gazella , Antilope , Procapra , Antidorcas , Litocranius , and Ammodorcas (O’Reagan, 1984; Corbet and Hill, 1986; Groves, 1988). Genus Gazella comprises one extinct species, and from 10 to 15 surviving species, usually divided into three sub-genera, Nanger , Gazella, and Trachelocele (Corbet, 1978; O’Reagan, 1984; Corbet and Hill, 1986; Groves, 1988). Gazella leptoceros is either included in the sub-genus Gazella (Groves, 1969; O’Reagan, 1984), or considered as forming, along with the Asian gazelle Gazella subgutturosa , the sub-genus Trachelocele (Groves, 1988). The Gazella leptoceros. Sidi Toui National Parks. Tunisia. species comprises two sub-species, Gazella leptoceros leptoceros of © Renata Molcanova the Western Desert of Lower Egypt and northeastern Libya, and Gazella leptoceros loderi of the western and middle Sahara. These two forms seem geographically isolated from each other and ecologically distinct, so that they must, from a conservation biology point of view, be treated separately. 1.2. Nomenclature. 1.2.1. Scientific name. Gazella leptoceros (Cuvier, 1842) Gazella leptoceros leptoceros (Cuvier, 1842) Gazella leptoceros loderi (Thomas, 1894) 1.2.2. Synonyms. Antilope leptoceros, Leptoceros abuharab, Leptoceros cuvieri, Gazella loderi, Gazella subgutturosa loderi, Gazella dorcas, var.