Lasting Sorrow: Chinese Literati's Emotions on Their Journeys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Lute of Jade : Being Selections from the Classical Poets of China

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES IN MEMORY OF CARROLL ALCOTT PRESENTED BY CARROLL ALCOTT MEMORIAL LIBRARY FUND COMMITTEE xrbe Mist)om ot tbe iBast Secies Edited by L. CRANMER-BYNG Dr. S. A. KAPADIA A LUTE OF JADE TO PROFESSOR HERBERT GILES WISDOM OF THE EAST A LUTE OF JADE BEING SELECTIONS FROM THE CLASSICAL POETS OF CHINA RENDERED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY L. CRANMER-BYNG AUTHOR or "THE ODES OF CONFUCIUS*' ^'itb lutes of gold and lutes ofjade LiPo ^i.'i NEW YORK E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY 1915 Pnnttd hy Hoiell, Watson <t Viney, Ld., London and AyUAury, SngUmi. 3i77 C8S ^'5 CONTENTS Introduction 9 9 The Ancient Ballads . 12 Poetry before the T'angs The Poets of the T'ang Dynasty U A Poet's Emperor 18 Chinese Verse Form 22 The Influence of Religion on Chinese Poetry 23 Thb Odes of Confucius 29 32 Ch'U Yuan . The Land of Exile 32 Wang Sbng-ju 36 Ch'en TzC-ang 36 Sung Chih-wen 38 40 Kao-Shih . 40 Impressions of a Traveller Desolation 41 Mjsng Hao-jan 43 The Lost One 43 44 A Friend Expected 46 Ch'ang Ch'ien . 46 A Night on the Mountain 1495412 CONTENTS TS'BN-TS'AN. A Dream of Spring Tu Fu The Little Rain . A Night of Song . The Recruiting Sergeant Chants of Autumn UTo To the City of Nan-king Memories with the Dusk Return An Emperor's Love On the Banks of Jo-yeh Thoughts in a Tranquil Night The Guild of Good-fellowship Under the Moon . -

The Sunday Book of Poetry

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fe Wi ilkWMWM niiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii no THE GIFT OF Prof .Aubrey Tealdi iiiiuiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiMiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiuiHiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii.il!!: tJU* A37f , k LONDON : R. CLAY, SON, AND TAYLOR, PRINTERS, BREAD STREET HILL. Fourth Thousand. THE SUNDAY BOOK OF POETRY SELECTED AND ARRANGED BY V,v ., .O" F^-A*! EX A N D E R AUTHOR OF "HYMNS FOR LITTLE CHILDREN," ETC. Jfambou srab Cambridge : MACMILLAN AND CO. 1865. A Taip in&e' when tonat v.... <lu: lie Ria sev ate Pi di . B IT- PREFACE The present volume will, it is hoped, be found to contain a selection of Sacred Poetry, of such a character as can be placed with profit and pleasure in the hands of intelligent children from eight to fourteen years of age, both on Sundays and at other times. It may be well for the Compiler to make some remarks upon the principles which have been adopted in the present selection. Dr. Johnson has said that " the word Sacred should never be applied but where some reference may be made to a higher Being, or where some duty is exacted, or implied." The Compiler be lieves she has selected few poems whose insertion may not be justified by this definition, though several perhaps may not be of such a nature as are popularly termed sacred. Those which appear under the division of the Incarnate Word, and of Praise, and Prayer, are of course in some cases directly hymns, and in all cases founded upon the great doctrines of the Christian faith, or upon the events of the Redeemer's life. -

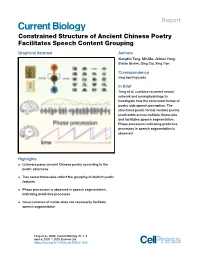

Constrained Structure of Ancient Chinese Poetry Facilitates Speech Content Grouping

Report Constrained Structure of Ancient Chinese Poetry Facilitates Speech Content Grouping Graphical Abstract Authors Xiangbin Teng, Min Ma, Jinbiao Yang, Stefan Blohm, Qing Cai, Xing Tian Correspondence [email protected] In Brief Teng et al. combine recurrent neural network and neurophysiology to investigate how the structured format of poetry aids speech perception. The structured poetic format renders poems predictable across multiple timescales and facilitates speech segmentation. Phase precession indicating predictive processes in speech segmentation is observed. Highlights d Listeners parse ancient Chinese poetry according to the poetic structures d Two neural timescales reflect the grouping of distinct poetic features d Phase precession is observed in speech segmentation, indicating predictive processes d Co-occurrence of words does not necessarily facilitate speech segmentation Teng et al., 2020, Current Biology 30, 1–7 April 6, 2020 ª 2020 Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.059 Please cite this article in press as: Teng et al., Constrained Structure of Ancient Chinese Poetry Facilitates Speech Content Grouping, Current Biology (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.01.059 Current Biology Report Constrained Structure of Ancient Chinese Poetry Facilitates Speech Content Grouping Xiangbin Teng,1,8 Min Ma,2,8 Jinbiao Yang,3,4,5,6 Stefan Blohm,1 Qing Cai,4,7 and Xing Tian3,4,7,9,* 1Department of Neuroscience, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, Frankfurt 60322, Germany 2Google Inc., 111 8th Avenue, New -

Ming-Qing Women's Song Lyrics to the Tune Man Jiang Hong

engendering heroism: ming-qing women’s song 1 ENGENDERING HEROISM: MING-QING WOMEN’S SONG LYRICS TO THE TUNE MAN JIANG HONG* by LI XIAORONG (McGill University) Abstract The heroic lyric had long been a masculine symbolic space linked with the male so- cial world of career and achievement. However, the participation of a critical mass of Ming-Qing women lyricists, whose gendered consciousness played a role in their tex- tual production, complicated the issue. This paper examines how women crossed gen- der boundaries to appropriate masculine poetics, particularly within the dimension of the heroic lyric to the tune Man jiang hong, to voice their reflections on larger historical circumstances as well as women’s gender roles in their society. The song lyric (ci 詞), along with shi 詩 poetry, was one of the dominant genres in which late imperial Chinese women writers were active.1 The two conceptual categories in the aesthetics and poetics of the song lyric—“masculine” (haofang 豪放) and “feminine” (wanyue 婉約)—may have primarily referred to the textual performance of male authors in the tradition. However, the participation of a critical mass of Ming- Qing women lyricists, whose gendered consciousness played a role in * This paper was originally presented in the Annual Meeting of the Association for Asian Studies, New York, March 27-30, 2003. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor Grace S. Fong for her guidance and encouragement in the course of writing this pa- per. I would like to also express my sincere thanks to Professors Robin Yates, Robert Hegel, Daniel Bryant, Beata Grant, and Harriet Zurndorfer and to two anonymous readers for their valuable comments and suggestions that led me to think further on some critical issues in this paper. -

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2020 Committee: Zev Handel William Boltz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2020 Grainger Lanneau University of Washington Abstract Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor Zev Handel Asian Languages and Literature Middle Chinese glottal stop Ying [ʔ-] initials usually develop into zero initials with rare occasions of nasalization in modern day Sinitic1 languages and Sino-Vietnamese. Scholars such as Edwin Pullyblank (1984) and Jiang Jialu (2011) have briefly mentioned this development but have not yet thoroughly investigated it. There are approximately 26 Sino-Vietnamese words2 with Ying- initials that nasalize. Scholars such as John Phan (2013: 2016) and Hilario deSousa (2016) argue that Sino-Vietnamese in part comes from a spoken interaction between Việt-Mường and Chinese speakers in Annam speaking a variety of Chinese called Annamese Middle Chinese AMC, part of a larger dialect continuum called Southwestern Middle Chinese SMC. Phan and deSousa also claim that SMC developed into dialects spoken 1 I will use the terms “Sinitic” and “Chinese” interchangeably to refer to languages and speakers of the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. 2 For the sake of simplicity, I shall refer to free and bound morphemes alike as “words.” 1 in Southwestern China today (Phan, Desousa: 2016). Using data of dialects mentioned by Phan and deSousa in their hypothesis, this study investigates initial nasalization in Ying-initial words in Southwestern Chinese Languages and in the 26 Sino-Vietnamese words. -

Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 489 SO 025 360 AUTHOR Yu-ning, Li, Ed. TITLE Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM Johnson & Associates, 257 East South St., Franklin, IN 46131-2422 (paperback: $25; clothbound: ISBN-1-880938-008, $39; shipping: $3 first copy, $0.50 each additional copy). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chinese Culture; *Cultural Images; Females; Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Legends; Mythology; Role Perception; Sexism in Language; Sex Role; *Sex Stereotypes; Sexual Identity; *Womens Studies; World History; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Asian Culture; China; '`Chinese Literature ABSTRACT This book examines the ways in which Chinese literature offers a vast array of prospects, new interpretations, new fields of study, and new themes for the study of women. As a result of the global movement toward greater recognition of gender equality and human dignity, the study of women as portrayed in Chinese literature has a long and rich history. A single volume cannot cover the enormous field but offers volume is a starting point for further research. Several renowned Chinese writers and researchers contributed to the book. The volume includes the following: (1) Introduction (Li Yu- Wing);(2) Concepts of Redemption and Fall through Woman as Reflected in Chinese Literature (Tsung Su);(3) The Poems of Li Qingzhao (1084-1141) (Kai-yu Hsu); (4) Images of Women in Yuan Drama (Fan Pen Chen);(5) The Vanguards--The Truncated Stage (The Women of Lu Yin, Bing Xin, and Ding Ling) (Liu Nienling); (6) New Woman vs. -

The Study on Translation of Chai Tou Feng by Lu You Based on House's

Advances in Intelligent Systems Research, volume 163 8th International Conference on Management, Education and Information (MEICI 2018) The Study on Translation of Chai Tou Feng by Lu You Based on House’s Translation Quality Assessment Mode Xiaoyan Wu Secondary Vocational and Technical School, Yingcheng, Hubei [email protected] Keywords: House’s Model of Translation Quality Assessment; Chai Tou Feng; Applicability Abstract. Song Ci is a kind of unique literary form in the history of Chinese culture, so it is difficult to translate it into English. This thesis applies House’s model of translation quality assessment to evaluate the English version of Chai Tou Feng by Lu You, which demonstrates its applicability and is helpful to future research of Tang poetry and Song Ci. Introduction Translation Quality Assessment Model, which was put forward by Juliane House in A Model of Translation Quality Assessment and Translation Quality Assessment: A Model Revisited, is considered as the first completely theoretical and practical translation quality assessment model in the field of international translation criticism. It is common to find out that a number of Chinese proses and novels were assessed by some theories, such as Transformational Generative Grammar and Equivalence Theory and so on. However, it is rare to follow House’s Translation Quality Assessment Model to assess literary works, especially Tang poetry and Song Ci, which occupy important positions in the ancient Chinese literature. Therefore, this thesis applies House’s Translation Quality Assessment Model to analyzing Chai Tou Feng by Lu You and its English version. On one hand, it helps us to apply abstract translation theories to analyzing literary works, films and Tv series; on the other hand, it contributes to spreading Chinese culture to the world, which enables the world to learn China better. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

Shijing and Han Yuefu

SONGS THAT TOUCH OUR SOUL A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FOLK SONGS IN TWO CHINESE CLASSICS: SHIJING AND HAN YUEFU by Yumei Wang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Art Graduate Department of the East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Yumei Wang 2012 SONGS THAT TOUCH OUR SOUL A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FOLK SONGS IN TWO CHINESE CLASSICS: SHIJING AND HAN YUEFU Yumei Wang Master of Art Graduate Department of the East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2012 Abstract The subject of my thesis is the comparative study of classical Chinese folk songs. Based on Jeffrey Wainwright, George Lansing Raymond, and Liu Xie’s theories, this study was conducted from four perspectives: theme, content, prosody structure and aesthetic features. The purposes of my thesis are to trace the originality of 160 folk songs in Shijing and 47 folk songs in Han yuefu , to illuminate the origin of Chinese folk songs and to demonstrate the secularism reflected in Chinese folk songs. My research makes contribution to the following four areas: it explores the relation between folk songs in Shijing and Han yuefu and compares the similarities and differences between them ; it reveals the poetic kinship between Shijing and Han yuefu; it evaluates the significance of the common people’s compositions; and it displays the unique artistic value and cultural influence of Chinese early folk songs. ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Professor Graham Sanders for his supervision, inspirations, and encouragements during my two years M.A study in the Department of East Asian Studies at University of Toronto. -

Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Author(S): Eugene Yuejin Wang Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Author(s): Eugene Yuejin Wang Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 76, No. 3, (Sep., 1994), pp. 511-534 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3046042 Accessed: 17/04/2008 11:17 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Eugene Yuejin Wang a 1 Jian (looking/mirror), stages of development of ancient ideograph (adapted from Zhongwendazzdian [Encyclopedic dictionary of the Chinese language], Taipei, 1982, vi, 9853) History as Mirror: Trope and Artifact people. -

An Explanation of Gexing

Front. Lit. Stud. China 2010, 4(3): 442–461 DOI 10.1007/s11702-010-0107-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE XUE Tianwei, WANG Quan An Explanation of Gexing © Higher Education Press and Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Gexing 歌行 is a historical and robust prosodic style that flourished (not originated) in the Tang dynasty. Since ancient times, the understanding of the prosody of gexing has remained in debate, which focuses on the relationship between gexing and yuefu 乐府 (collection of ballad songs of the music bureau). The points-of-view held by all sides can be summarized as a “grand gexing” perspective (defining gexing in a broad sense) and four major “small gexing” perspectives (defining gexing in a narrow sense). The former is namely what Hu Yinglin 胡应麟 from Ming dynasty said, “gexing is a general term for seven-character ancient poems.” The first “small gexing” perspective distinguishes gexing from guti yuefu 古体乐府 (tradition yuefu); the second distinguishes it from xinti yuefu 新体乐府 (new yuefu poems with non-conventional themes); the third takes “the lyric title” as the requisite condition of gexing; and the fourth perspective adopts the criterion of “metricality” in distinguishing gexing from ancient poems. The “grand gexing” perspective is the only one that is able to reveal the core prosodic features of gexing and give specification to the intension and extension of gexing as a prosodic style. Keywords gexing, prosody, grand gexing, seven-character ancient poems Received January 25, 2010 XUE Tianwei ( ) College of Humanities, Xinjiang Normal University, Urumuqi 830054, China E-mail: [email protected] WANG Quan International School, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing 100029, China E-mail: [email protected] An Explanation of Gexing 443 The “Grand Gexing” Perspective and “Small Gexing” Perspective Gexing, namely the seven-character (both unified seven-character lines and mixed lines containing seven character ones) gexing, occupies an equal position with rhythm poems in Tang dynasty and even after that in the poetic world. -

Dissertation Section 1

Elegies for Empire The Poetics of Memory in the Late Work of Du Fu (712-770) Gregory M. Patterson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 ! 2013 Gregory M. Patterson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Elegies for Empire: The Poetics of Memory in the Late Work of Du Fu (712-770) Gregory M. Patterson This dissertation explores highly influential constructions of the past at a key turning point in Chinese history by mapping out what I term a poetics of memory in the more than four hundred poems written by Du Fu !" (712-770) during his two-year stay in the remote town of Kuizhou (modern Fengjie County #$%). A survivor of the catastrophic An Lushan rebellion (756-763), which transformed Tang Dynasty (618-906) politics and culture, Du Fu was among the first to write in the twilight of the Chinese medieval period. His most prescient anticipation of mid-Tang concerns was his restless preoccupation with memory and its mediations, which drove his prolific output in Kuizhou. For Du Fu, memory held the promise of salvaging and creatively reimagining personal, social, and cultural identities under conditions of displacement and sweeping social change. The poetics of his late work is characterized by an acute attentiveness to the material supports—monuments, rituals, images, and texts—that enabled and structured connections to the past. The organization of the study attempts to capture the range of Du Fu’s engagement with memory’s frameworks and media. It begins by examining commemorative poems that read Kuizhou’s historical memory in local landmarks, decoding and rhetorically emulating great deeds of classical exemplars.