Gifting the Bear and a Nostalgic Desire for Childhood Innocence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLUB MAGAZINE the Magazine for Steiff Club Members – August 2017 EDITORIAL

CLUB MAGAZINE The magazine for Steiff Club members – August 2017 EDITORIAL Dear Steiff friends, It's 1 July, and despite the As already mentioned earlier, inconsistencies of the weather, the we are also presenting the Steiff Sommer is again attracting Margarete Steiff Edition 2017 to lots of visitors from near and far. you in this issue. This homage The magazine is about to go to to Richard Steiff concludes the press, and it's high time I get on exclusive series that is dedicated with the editorial. I'm not finding to Margarete Steiff's nephews. it so easy at the moment, though, Please refer to pages 14 to 17. Our because my thoughts are revolving portraits of Margarete's nephews entirely around yesterday. To me also come to a close in this issue. personally, the days in the run-up Apart from that, the magazine to 30 June were very special, and contains both historical and the preparations for the journey contemporary topics of interest for through “25 Years of the Steiff you, which I hope you will enjoy Club” awoke so many memories. reading. Incidentally, the next issue Our efforts were rewarded when we will also honour the designers were able to welcome over 600 Club amongst you who took part in the members to the Giengen Schranne! competition in the February issue. I'd like to take this opportunity to You can start looking forward to it thank you all again for coming. I now! hope you all enjoyed looking back at 25 years of the Club’s history. -

October 20 Online Auction

10/02/21 12:35:21 October 20 Online Auction Auction Opens: Thu, Oct 15 6:00pm ET Auction Closes: Tue, Oct 20 7:00pm ET Lot Title Lot Title 1 ***UPDATE: Sells To The Highest Bidder*** 1010 1889 D Morgan Dollar Coin From Estate Carbine Rifle - Model 1894 Winchester 30-30 1011 14K Gold Plated Indian Head 1898 Cent, Cal, Circa 1947 Serial #1588547, Wood & Very Nice Statement Ring Size 11, Good Steel, Very Good Condition, Works as New, Condition Looks Like New, First Production Post WWII ***Preview Will Be 1PM To 2PM On 1012 Silvertone With Turquoise Indian Style Saturday*** **Sells with Owner's Bracelet, Good Condition Confirmation** Note: This Item is Located 1013 1944 Iran 1 Rial 1975 Iran Irial 1977 Iran 5 Off-Site. PayPal is NOT Accepted as a Form Rial Unc. Coins, Hard to Find of Payment for This Item. Please Contact 1014 New Black Rhodium Plated Princess Cut 1BID Office to Arrange for Pickup with Amethyst Ring Size 7 1/2, Impressive Seller. 1015 Five 1964 Half Dollar Coins and One 1973 10 Vermont Country Eggnog Bottle and Half Dollar Coin From Estate Osterizer, Mini Blend Container, Good Condition, 4" to 8 1/2"H 1016 Genuine Stamped 925 Poison Ring, Has Nice Garnet Looking Stone On Top, Use Your 100 Cool Wood Golf Ball Display or Your Use Favorite Poison, You Don't See These Very Rack, Missing Adornments At Three Often, Size 9 Corners, Good Condition Otherwise, I Bolts for Hanging, 22"W x 39"H 1017 1957 P Franklin Silver Half Dollar, Choice Unc. -

The Court of International Trade Holds Fantasy Toys Eligible for Duty-Free Status Under the Generalized System of Preferences

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 13 Number 2 Article 10 Spring 1988 How E.T. Got through Customs: The Court of International Trade Holds Fantasy Toys Eligible for Duty-Free Status under the Generalized System of Preferences Patti L. Holt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Part of the Commercial Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Patti L. Holt, How E.T. Got through Customs: The Court of International Trade Holds Fantasy Toys Eligible for Duty-Free Status under the Generalized System of Preferences, 13 N.C. J. INT'L L. 387 (1988). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol13/iss2/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How E.T. Got Through Customs: The Court of International Trade Holds Fantasy Toys Eligible for Duty-Free Status Under the Generalized System of Preferences E.T., the extraterrestrial character in the Stephen Spielberg movie of the same name, I recently appeared in a new role as the star of an international trade case. The plot involved the economic de- velopment of third world countries and the growing importance of the United States as the world's biggest consumer of stuffed toys. In order to advance both of these interests, the Court of International Trade (CIT) overruled previous trade cases and redefined a tariff classification in order to allow stuffed figures of E.T. -

1 Part One. Parts of the Sentence. Identify the Function of The

Part One. Parts of the Sentence. Identify the function of the underlined portion in sentences 1-26. 1. With his customary eagerness to begin his Scranton Prep school day, John Nicholson bounded into the school lobby and greeted Mrs. Nagurney, the assistant principal, with a cheerful “Good morning!” A. predicate nominative B. adjectival phrase C. appositive phrase D. noun clause 2. “Hello, John,” Mrs. Nagurney responded and smiled as John breezed past her on his way to find his friends, Frank Herndon, Buddy Adams, and Jim Timmons. A. past participial phrase B. adverbial clause C. noun clause D. infinitive phrase 3. Mrs. Nagurney noticed that John was carrying the latest edition of the popular magazine Nature Conservancy and remembered that he and most of his classmates were quite enthusiastic in their commitment to conservation. A. predicate nominative B. predicate adjective C. indirect object D. direct object 4. In fact, John had recently told her that he, Frank, Buddy, and Jim, as well as several other sophomore boys, were working on their forestry badges in their quest to become Eagle Scouts. Mrs. Nagurney had commended these students for their effort to achieve this highest rank in Boy Scouts of America. A. indirect object B. direct object C. object of the preposition D. predicate nominative 5. Seeing his friends at their third-floor lockers, John waved the magazine and said, “Wait until you see this awesome issue! It’s all about the centennial, the one-hundredth anniversary, of the National Park Service on August 25, 2016.” A. gerund phrase B. nonessential clause C. -

STAAR Grade 3 Reading TB Released 2017

STAAR® State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness GRADE 3 Reading Administered May 2017 RELEASED Copyright © 2017, Texas Education Agency. All rights reserved. Reproduction of all or portions of this work is prohibited without express written permission from the Texas Education Agency. READING Reading Page 3 Read the selection and choose the best answer to each question. Then fill in theansweronyouranswerdocument. from Jake Drake, Teacher’s Pet by Andrew Clements 1 When I was in third grade, we got five new computers in our classroom. Mrs. Snavin was my third-grade teacher, and she acted like computers were scary, especially the new ones. She always needed to look at a how-to book and the computer at the same time. Even then, she got mixed up a lot. Then she had to call Mrs. Reed, the librarian, to come and show her what to do. 2 So it was a Monday morning in May, and Mrs. Snavin was sitting in front of a new computer at the back of the room. She was confused about a program we were supposed to use for a math project. My desk was near the computers, and I was watching her. 3 Mrs. Snavin looked at the screen, and then she looked at this book, and then back at the screen again. Then she shook her head and let out this big sigh. I could tell she was almost ready to call Mrs. Reed. 4 I’ve always liked computers, and I know how to do some stuff with them. Like turn them on and open programs, play games and type, make drawings, and build Web pages—things like that. -

Finding Aid to the GUND, Inc. Records, 1912-2002

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play GUND, Inc. Records Finding Aid to the GUND, Inc. Records, 1912-2002 Summary Information Title: GUND, Inc. records Creator: GUND, Inc. (primary) ID: 115.915 Date: 1912-2002 (inclusive); 1942-1969, 1984-1998 (bulk) Extent: 38 linear feet Language: The materials in this collection are in English. Abstract: The GUND, Inc. records are a compilation of historic business records from GUND, Inc. The bulk of the materials are dated between 1942 and 1969, and again from 1984-1998. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, the company has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Custodial History: The GUND, Inc. records were donated to The Strong in March 2015 as a gift from GUND, Inc. The papers were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 115.915. The records were received from Bruce Raiffe, President of GUND, Inc., in 53 boxes, along with a donation of historic GUND plush toys and GUND trade catalogs. Preferred citation for publication: GUND, Inc. records, Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong Processed by: Julia Novakovic, June-October 2015 Controlled Access Terms Personal Names Leibovitz, Annie Raiffe, Bruce S. -

Teddy Bear Featured in Prima December 2008 of Next St; Rem Remaining; Rep Row

Teddy Bear Featured in Prima December 2008 of next st; rem remaining; rep row. Next row [Skpo, k2, k2tog] 4 times. Shape top repeat; skpo sl 1, k1, pass 16 sts. K 1 row. Next row [Skpo, k2tog] Next row K2tog tbl, k8, k2tog, k1, k2tog tbl, slipped st over; sk2togpo slip 4 times. 8 sts. K 1 row. Next row [Skpo, k8, k2tog. 21 sts. K 1 row. Next row K2tog 1, k2tog, pass slipped st over; k2tog] twice. 4 sts. Break yarn, thread tbl, k6, k2tog, k1, k2tog tbl, k6, k2tog. 17 st(s) stitch(es); tbl through back through rem sts, pull up and secure. sts. K 1 row. Next row K2tog tbl, k4, k2tog, loop; tog together. k1, k2tog tbl, k4, k2tog. 13 sts. K 1 row. SNOUT Next row K2tog tbl, k2, k2tog, k1, k2tog tbl, BODY Make 1 piece. With 3mm needles, cast k2, k2tog. 9 sts. K 1 row. Next row K2tog Make 2 pieces, beg at on 36 sts. K 10 rows. Next row * K1, tbl, k2tog, k1, k2tog tbl, k2tog. 5 sts. K 1 shoulders. With 3mm needles, k2tog; rep from * to end. 24 sts. K 1 row. row. Next row K2tog tbl, k1, k2tog. 3 sts. cast on 22 sts. K 10 rows. Cont Next row [K2tog] to end. 12 sts. K 1 row. Next row K3tog and fasten off. in garter st and inc 1 st at each Break yarn, thread through sts, pull up and end of next row and 6 foll 6th secure. EARS rows. 36 sts. -

A Downloadable Pdf Version

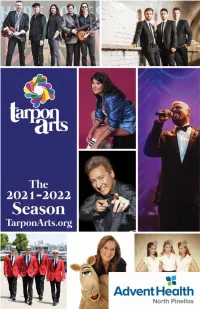

Tarpon Arts operates in four distinct venues providing patrons with affordable, world-class arts, culture and entertainment. Performing Arts Center 324 Pine Street Tarpon Arts presents stimulating, engaging, and educational (inside City Hall) performances, workshops, festivals, concerts, and visual Open for shows only arts that celebrate the unique heritage and culture of State-of-the-art Tarpon Springs and the State of Florida, while bringing 295 seat theater nationally-acclaimed artists to the community establishing Tarpon Springs as a dynamic cultural destination. Cultural Center 2021 - 2022 Season Sponsor 101 South Pinellas Avenue 70 seat theater Performances Exhibitions Special Events Heritage Museum & Media Hospitality Sponsors Sponsors Tarpon Arts Ticket Office 100 Beekman Lane Monday - Friday 10:00 AM - 4:00 PM tampabay.com $5.00 admission Greek History & Ecology Wings Performances | Special Events Grant Partners 1883 Safford House 23 Parkin Court Wednesday - Friday 11:00 AM - 3:00 PM $5.00 admission Guided Tours | Special Events Tarpon Arts is proud to have the support for all community theatre performances at the Cultural Center and The Art of Health in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. 1 2 SEASON AT A GLANCE SEASON AT A GLANCE AUGUST 2021 FEBRUARY 2022 14 Welcome Back Concert in the Park - ELLADA! 5 Changes in Latitudes - Jimmy Buffett Tribute 11-13, 18-20 Funny Little Thing Called Love 11 Destination Motown Featuring the Sensational Soul Cruisers SEPTEMBER 2021 20 Icons Show Starring Tony Pace 11-12, -

Chapter 18 Video, “The Stockyard Jungle,” Portrays the Horrors of the Meatpacking Industry First Investigated by Upton Sinclair

The Progressive Movement 1890–1919 Why It Matters Industrialization changed American society. Cities were crowded with new immigrants, working conditions were often bad, and the old political system was breaking down. These conditions gave rise to the Progressive movement. Progressives campaigned for both political and social reforms for more than two decades and enjoyed significant successes at the local, state, and national levels. The Impact Today Many Progressive-era changes are still alive in the United States today. • Political parties hold direct primaries to nominate candidates for office. • The Seventeenth Amendment calls for the direct election of senators. • Federal regulation of food and drugs began in this period. The American Vision Video The Chapter 18 video, “The Stockyard Jungle,” portrays the horrors of the meatpacking industry first investigated by Upton Sinclair. 1889 • Hull House 1902 • Maryland workers’ 1904 opens in 1890 • Ida Tarbell’s History of Chicago compensation laws • Jacob Riis’s How passed the Standard Oil the Other Half Company published ▲ Lives published B. Harrison Cleveland McKinley T. Roosevelt 1889–1893 ▲ 1893–1897 1897–1901 1901–1909 ▲ ▲ 1890 1900 ▼ ▼ ▼▼ 1884 1900 • Toynbee Hall, first settlement • Freud’s Interpretation 1902 house, established in London of Dreams published • Anglo-Japanese alliance formed 1903 • Russian Bolshevik Party established by Lenin 544 Women marching for the vote in New York City, 1912 1905 • Industrial Workers of the World founded 1913 1906 1910 • Seventeenth 1920 • Pure Food and • Mann-Elkins Amendment • Nineteenth Amendment Drug Act passed Act passed ratified ratified, guaranteeing women’s voting rights ▲ HISTORY Taft Wilson ▲ ▲ 1909–1913 ▲▲1913–1921 Chapter Overview Visit the American Vision 1910 1920 Web site at tav.glencoe.com and click on Chapter ▼ ▼ ▼ Overviews—Chapter 18 to preview chapter information. -

GIFTS by AGE, and GENDER. If You Wish to Give a Gift Card, Please Buy

Thank you for spreading Christmas joy this year! The following items are suggested gifts to meet the needs and wants of families served by CU Mission. This is a general list only, and gifts re- ceived will go to children not sponsored. Please DO NOT WRAP GIFTS, but LABEL GIFTS BY AGE, and GENDER. If you wish to give a Gift Card, please buy from: Target, Wal-Mart, H&M, Old Navy, GameStop, Forever 21, Payless, Macy’s, Best Buy, or Marshall’s. Be sure to mark the amount on the card or envelope. Please do not include food or candy with any gift. All gifts are requested by December 10, 2018. Your kindness and generosity will make a world of difference in the life of a child this Christmas Season. Infant – 1 year old Ages 2 - 4 years Ages 2 - 4 years The Beginner's Bible: Timeless The Beginner's Bible: Timeless Toy Musical Instruments Children's Stories Children's Stories Magnetic Alphabet Set Stuffed toys Stuffed toys/Pillow Pets Doctor Dress up set Toy cars and trucks (fire trucks, Toy cars and trucks Hot Wheels T-Ball Set police cars, etc.) Baby Alive My Little Pony Set Baby Books Walk-N-Roll/Ride-on toys Play-Doh Baby Einstein toys/games Books Chunky Puzzle Fisher-Price Brilliant Basics Ba- Leap Frog Learning games Play tool set by's First Blocks Write and Learn Toys Veggie Tales, Disney, Hello Kit- Leap Frog Toys V-Tech Learning games ty, Dora the Explorer, Transform- ers or Marvel (including videos) Teether activity toys Playschool toys Balls Playhouse/Playset Bath time fun toys Play House Toys (Play Kitchen, Paw Patrol Bumpy Ball Picnic Basket, etc.) Teddy Ruxpin Vtech Toys (Learning Walker, Children’s puzzle Mr. -

Collectors Catalogue Autumn/Winter 2017

Collectors Catalogue Autumn/Winter 2017 Contents Steiff Collectors Manufacturing 4-5 Materials 6 Perfected unique specimen 7 Replicas 8-11 Limited Editions 12-25 Designer's Choice 26-29 Licensed Pieces 30-37 Country Exclusives 38-45 Steiff Club 46-50 Manufacturing In keeping with tradition Some things may be thousands or several hundred years old – but they cannot be significantly improved. However, they can be continued at the highest level: That’s why we like Steiff’s manufacturing concept so much. “Manufacture” as an old Latin term: “manus”, the hand, “facere” to do, build or produce something. And if this thought, this concept hadn’t already existed, we at Steiff would surely have invented it. Creating something with your hands. Allowing skill, experience and craftsmanship to flow into the creation process. Bringing in passion, commitment and lots of love for detail into the creative process – in order to bring something extraordinary and unique to life. But that’s what it is: For us, manufacture is far more than just a fashionable word. Because, true to the spirit of our founder Margarete Steiff, we are fully committed to not only honour the tradition of manufacture, but to continually imbue it with new life. Day after day. With every animal leaving our company so steeped in tradition. www.steiff.com 5 Materials Millimetre by millimetre and thread for thread: simply the best. Those wanting to create something special and unique of lasting value will need nothing less than the perfect “ingredients”. This not only applies to many other areas but especially to our Steiff manufacture, where we only use “ingredients” of the highest quality: for every Steiff animal, from head to paw. -

The Angelic Bears Volume 20 – No

The Angelic Bears Volume 20 – No. 3 August 1, 2021 Grand Chapter of Maine, Order of the Eastern Star Catherine J. Wood, Worthy Grand Matron Arthur C. Dunlap, Worthy Grand Patron _____________________________________________________________________________ Special Project Needs You! Triennial Assembly The work day for the Worthy Grand Matron’s Instead of the in-person Triennial Assembly that Special Project will be held on Monday, August was to be held in Salt Lake City, there will be a 16 at the Auburn Masonic Hall at 1021 Turner Virtual Assembly for two days and it will be held Street in Auburn. Coffee and refreshments will at the Belmont House in Washington D.C., the commence at 9 a.m. with actual work starting at Eastern Star Headquarters. 10 a.m. This is a casual dress event and all are welcome to attend. Nancy Jacobs and Lynda The dates are Wednesday, November 3rd and Bell are the Co-Chairmen for this event with Thursday, November 4th. The first day will be the Jolene Farnsworth and Theo Heald as the Business Session and the second day will be the refreshment committee. Installation of the 2021-2024 General Grand Chapter Officers. Grand Family Reception Any member of the Order may attend virtually The Angels Gather Here Grand Family either or both of these two days with the deadline Reception will be held on August 21 for registration being September 1. All registered commencing at 11 a.m. with a social hour and a and fee paid members ($25) will receive by mail noon luncheon at Jeff’s Catering, 151 Littlefield an attractive souvenir Welcome Bag and the Road in Brewer.