Theodore Roosevelt and the Political Rhetoric of Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Part One. Parts of the Sentence. Identify the Function of The

Part One. Parts of the Sentence. Identify the function of the underlined portion in sentences 1-26. 1. With his customary eagerness to begin his Scranton Prep school day, John Nicholson bounded into the school lobby and greeted Mrs. Nagurney, the assistant principal, with a cheerful “Good morning!” A. predicate nominative B. adjectival phrase C. appositive phrase D. noun clause 2. “Hello, John,” Mrs. Nagurney responded and smiled as John breezed past her on his way to find his friends, Frank Herndon, Buddy Adams, and Jim Timmons. A. past participial phrase B. adverbial clause C. noun clause D. infinitive phrase 3. Mrs. Nagurney noticed that John was carrying the latest edition of the popular magazine Nature Conservancy and remembered that he and most of his classmates were quite enthusiastic in their commitment to conservation. A. predicate nominative B. predicate adjective C. indirect object D. direct object 4. In fact, John had recently told her that he, Frank, Buddy, and Jim, as well as several other sophomore boys, were working on their forestry badges in their quest to become Eagle Scouts. Mrs. Nagurney had commended these students for their effort to achieve this highest rank in Boy Scouts of America. A. indirect object B. direct object C. object of the preposition D. predicate nominative 5. Seeing his friends at their third-floor lockers, John waved the magazine and said, “Wait until you see this awesome issue! It’s all about the centennial, the one-hundredth anniversary, of the National Park Service on August 25, 2016.” A. gerund phrase B. nonessential clause C. -

STAAR Grade 3 Reading TB Released 2017

STAAR® State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness GRADE 3 Reading Administered May 2017 RELEASED Copyright © 2017, Texas Education Agency. All rights reserved. Reproduction of all or portions of this work is prohibited without express written permission from the Texas Education Agency. READING Reading Page 3 Read the selection and choose the best answer to each question. Then fill in theansweronyouranswerdocument. from Jake Drake, Teacher’s Pet by Andrew Clements 1 When I was in third grade, we got five new computers in our classroom. Mrs. Snavin was my third-grade teacher, and she acted like computers were scary, especially the new ones. She always needed to look at a how-to book and the computer at the same time. Even then, she got mixed up a lot. Then she had to call Mrs. Reed, the librarian, to come and show her what to do. 2 So it was a Monday morning in May, and Mrs. Snavin was sitting in front of a new computer at the back of the room. She was confused about a program we were supposed to use for a math project. My desk was near the computers, and I was watching her. 3 Mrs. Snavin looked at the screen, and then she looked at this book, and then back at the screen again. Then she shook her head and let out this big sigh. I could tell she was almost ready to call Mrs. Reed. 4 I’ve always liked computers, and I know how to do some stuff with them. Like turn them on and open programs, play games and type, make drawings, and build Web pages—things like that. -

Teddy Bear Featured in Prima December 2008 of Next St; Rem Remaining; Rep Row

Teddy Bear Featured in Prima December 2008 of next st; rem remaining; rep row. Next row [Skpo, k2, k2tog] 4 times. Shape top repeat; skpo sl 1, k1, pass 16 sts. K 1 row. Next row [Skpo, k2tog] Next row K2tog tbl, k8, k2tog, k1, k2tog tbl, slipped st over; sk2togpo slip 4 times. 8 sts. K 1 row. Next row [Skpo, k8, k2tog. 21 sts. K 1 row. Next row K2tog 1, k2tog, pass slipped st over; k2tog] twice. 4 sts. Break yarn, thread tbl, k6, k2tog, k1, k2tog tbl, k6, k2tog. 17 st(s) stitch(es); tbl through back through rem sts, pull up and secure. sts. K 1 row. Next row K2tog tbl, k4, k2tog, loop; tog together. k1, k2tog tbl, k4, k2tog. 13 sts. K 1 row. SNOUT Next row K2tog tbl, k2, k2tog, k1, k2tog tbl, BODY Make 1 piece. With 3mm needles, cast k2, k2tog. 9 sts. K 1 row. Next row K2tog Make 2 pieces, beg at on 36 sts. K 10 rows. Next row * K1, tbl, k2tog, k1, k2tog tbl, k2tog. 5 sts. K 1 shoulders. With 3mm needles, k2tog; rep from * to end. 24 sts. K 1 row. row. Next row K2tog tbl, k1, k2tog. 3 sts. cast on 22 sts. K 10 rows. Cont Next row [K2tog] to end. 12 sts. K 1 row. Next row K3tog and fasten off. in garter st and inc 1 st at each Break yarn, thread through sts, pull up and end of next row and 6 foll 6th secure. EARS rows. 36 sts. -

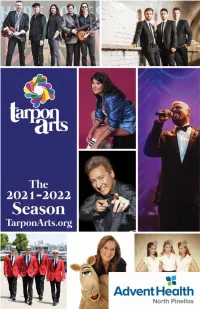

A Downloadable Pdf Version

Tarpon Arts operates in four distinct venues providing patrons with affordable, world-class arts, culture and entertainment. Performing Arts Center 324 Pine Street Tarpon Arts presents stimulating, engaging, and educational (inside City Hall) performances, workshops, festivals, concerts, and visual Open for shows only arts that celebrate the unique heritage and culture of State-of-the-art Tarpon Springs and the State of Florida, while bringing 295 seat theater nationally-acclaimed artists to the community establishing Tarpon Springs as a dynamic cultural destination. Cultural Center 2021 - 2022 Season Sponsor 101 South Pinellas Avenue 70 seat theater Performances Exhibitions Special Events Heritage Museum & Media Hospitality Sponsors Sponsors Tarpon Arts Ticket Office 100 Beekman Lane Monday - Friday 10:00 AM - 4:00 PM tampabay.com $5.00 admission Greek History & Ecology Wings Performances | Special Events Grant Partners 1883 Safford House 23 Parkin Court Wednesday - Friday 11:00 AM - 3:00 PM $5.00 admission Guided Tours | Special Events Tarpon Arts is proud to have the support for all community theatre performances at the Cultural Center and The Art of Health in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. 1 2 SEASON AT A GLANCE SEASON AT A GLANCE AUGUST 2021 FEBRUARY 2022 14 Welcome Back Concert in the Park - ELLADA! 5 Changes in Latitudes - Jimmy Buffett Tribute 11-13, 18-20 Funny Little Thing Called Love 11 Destination Motown Featuring the Sensational Soul Cruisers SEPTEMBER 2021 20 Icons Show Starring Tony Pace 11-12, -

Chapter 18 Video, “The Stockyard Jungle,” Portrays the Horrors of the Meatpacking Industry First Investigated by Upton Sinclair

The Progressive Movement 1890–1919 Why It Matters Industrialization changed American society. Cities were crowded with new immigrants, working conditions were often bad, and the old political system was breaking down. These conditions gave rise to the Progressive movement. Progressives campaigned for both political and social reforms for more than two decades and enjoyed significant successes at the local, state, and national levels. The Impact Today Many Progressive-era changes are still alive in the United States today. • Political parties hold direct primaries to nominate candidates for office. • The Seventeenth Amendment calls for the direct election of senators. • Federal regulation of food and drugs began in this period. The American Vision Video The Chapter 18 video, “The Stockyard Jungle,” portrays the horrors of the meatpacking industry first investigated by Upton Sinclair. 1889 • Hull House 1902 • Maryland workers’ 1904 opens in 1890 • Ida Tarbell’s History of Chicago compensation laws • Jacob Riis’s How passed the Standard Oil the Other Half Company published ▲ Lives published B. Harrison Cleveland McKinley T. Roosevelt 1889–1893 ▲ 1893–1897 1897–1901 1901–1909 ▲ ▲ 1890 1900 ▼ ▼ ▼▼ 1884 1900 • Toynbee Hall, first settlement • Freud’s Interpretation 1902 house, established in London of Dreams published • Anglo-Japanese alliance formed 1903 • Russian Bolshevik Party established by Lenin 544 Women marching for the vote in New York City, 1912 1905 • Industrial Workers of the World founded 1913 1906 1910 • Seventeenth 1920 • Pure Food and • Mann-Elkins Amendment • Nineteenth Amendment Drug Act passed Act passed ratified ratified, guaranteeing women’s voting rights ▲ HISTORY Taft Wilson ▲ ▲ 1909–1913 ▲▲1913–1921 Chapter Overview Visit the American Vision 1910 1920 Web site at tav.glencoe.com and click on Chapter ▼ ▼ ▼ Overviews—Chapter 18 to preview chapter information. -

“Cheat Sheet” for the Story of the Teddy

Teacher's "Cheat Sheet" for "MISSISSIPPI'S TEDDY BEAR" Following are answers to questions from the "Mississippi's Teddy Bear" story, as well as discussion and extension ideas. Reading Comprehension: Answer these questions about the story on a separate piece of paper. 1. Where does the story take place? Little Sunflower River, Mississippi 2. Why are bears rare in 1902? "People from the East, North, and South moved to Mississippi and cut the trees and drained the swamps, leaving no habitat for bears." They had nowhere to live! At the same time, bear hunting became popular and many, many bears were killed. 3. Who found the bear? The dogs, and Holt Collier, the bear hunting guide. What evidence from the text supports your answer? "Suddenly, the dogs howled loudly. They had found the scent of a bear!" ""Finally, the dogs saw the bear. It was old and hurt. Holt Collier blew his bugle to call the men." 4. Pretend you are President Roosevelt, what would you do next? How do you feel? 5. What would YOU have done? Additional Comprehension questions: 1. Why were the dogs there? Make an inference. To help the people find the bear and to chase the bear towards the people. They can hear and smell the scent of a bear very well. 2. What is the main idea of the story? Excessive bear hunting combined with habitat loss led to a severe reduction in bear population. There were not many bears left in Mississippi by the early 1900s. The name "teddy" bear came from a bear hunt in Mississippi where President Teddy Roosevelt refused to shoot an injured bear. -

LEAGUE NEWS the Newsletter of the League of Historical Societies of New Jersey

LEAGUE NEWS The Newsletter of the League of Historical Societies of New Jersey Vol. 37 No. 3 www.lhsnj.org August 2012 PRINCETON BATTLEFIELD AMONG Summer Meeting MOST ENDANGERED PLACES Friends of Waterloo On June 6, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named Princeton Village Battlefield in Princeton, N.J., to its 2012 list of America’s 11 Most Endangered October 20, 2012 Historic Places. This annual list spotlights important examples of the nation’s ************************* architectural, cultural, and natural heritage that are at risk of destruction or irrepa- Article, registration rable damage. More than 230 sites have been on the list over its 25-year history, form, and directions, and in that time, only a handful of listed sites have been lost. p. 23, 24 Princeton Battlefield is the site of a pivotal Revolutionary War battle where General George Washington rallied his forces to defeat British troops. Waged 235 years ago, the battle at Princeton was a crucial turning point in America’s War of Independence, marking one of General Washington’s first victories over professional British soldiers. Not only did Washington’s success inspire countless soldiers to renew their commissions, but it also reinvigorated financial and political support for the war effort throughout the colonies. Many historians believe that this battle, along with the Battle of Trenton, saved the American Revolution and changed the course of world history. A portion of the battle site is now threatened by a 15-unit housing development planned by the Institute for Advanced Study. As proposed, the project would radically alter the integrity of the historic landscape, which has never been built upon, burying or destroying potential archeological resources and dramatically changing the topography of the terrain — an important element of the battle and essential to interpreting the battle today. -

Teddy Bears & Soft Toys Dolls, Dolls' Houses and Traditional Toys

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Teddy Bears & Soft Toys Dolls, Dolls’ Houses and Traditional Toys 25th & 26th June 2019 at 11:00 Viewing: 24th June 2019 10:00-16:00 25th June 2019 09:00-16:00 9:00 Morning of each auction Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Fax: 0871 714 6905 [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Daniel Agnew Dolls & Teddy Bears Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price SAS Live Premium: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 22.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 27% of the Hammer Price Order of Auction Day One Tuesday 25th June 2019 at 11:00 Limited Edition & Collector’s Teddy Bears 1-133 Antique & Vintage Teddy Bears & Soft Toys 134-312 Day Two Wednesday 26th June 2019 at 11:00 Post-war Dolls 313-341 Antique & Vintage Dolls 342-474 Doll’s Accessories 475-528 Dolls’ Houses & Chattels 529- 631 Traditional Toys 632-715 The Bob Bura Puppet Collection 716-746 2 www.specialauctionservices.com Limited Edition & Collector’s Teddy Bears 1. A Steiff limited edition Winnie the Pooh, (20 inches), 2475 of 3500, in original bag, 2004 £60-80 6. A Steiff limited edition Harley 15. A Steiff limited edition Millennium Davidson 100th Anniversary Bear, 3424 of Band, 793 of 2000, musical, in original box 5000, in original box with certificate, 2003 with certificate, 2000 (has been dusty, the (some scuffing to box) £80-120 bears heads could do with a firmer brush, box flattened and worn) £150-200 7. -

National Historic Site

Theodore Roosevelt tsirthplace National Historic Site ro F.,,* '. e.' N " *" X h, ffi t W % * Fi'1 ru i:r+.:d 'ffi ffi t f mg:t Areas Proclaimed as National Parks During the Administration of Theodore Roosevelt Chalmette N.H.P. Louisiana Established as Chalmette Monument and Grounds, March 4, 1907 Crater Lake National Park Oregon Established May 22, l9O2 Devils Tower National Monument Wyoming Proclaimed September 24, 1906 El Morro National Monument New Mexico Proclaimed December 8, 1906 Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument New Mexico Proclaimed November 16, 1907 Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Proclaimed National Monument January 11, 1908 Jewel Cave National Monument South Dakota Proclaimed February 7, 1908 Lassen Volcanic National Park California Proclaimed as Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone National Monuments May 6, 1907 Mesa Verdes National Park Colorado Established June 29, 1906 Montezuma Castle National Monument Arizona Proclaimed December 8, 1906 Muir Woods National Monument California Proclaimed January 9, 1908 Natural Bridges National Monument Utah Proclaimed April 16, 1908 Olympic National Park Washington Proclaimed as Mount Olympus National Monument, March 2, lW9 Petrified Forest National Park Arizona Proclaimed December 8, 1906 as a National Monument Pinnacles National Monument California Proclaimed January 16, 1908 Platt National Park Oklahoma Authorized as Sulphur Springs Reservation, July 1, 1902 Redesignated Platt National Park, June 29, 1906 Chickasaw National Recreation Area as of March 17 , 1976 Tonto National Monument -

Progressive Era Notes

Progressive Era Notes Mr. Williams US History Akimel A-al Middle School Newspaper Notes! You will be taking your notes this unit in the form of a newspaper – because of how important the press was during the Progressive Era. Some days you may be able to use laptops to get your information, but with interim tests I never know if I will have enough You will eventually have four pieces of paper with your notes written on them, and you will staple them together before having me check them in order to give you completion points. 40 points total – 5 per points page, 8 sides on four pieces of paper. DO NOT LOSE THESE. If you do you will need to copy down all of the information from another student on a notebook piece of paper. The Gilded Age: The Gilded Age was a time of great wealth in America in the late 1800s/early 1900s. Something “gilded” is gold-plated: nice and shiny on the outside, but could be terrible on the inside. Many Americans felt like this was a perfect metaphor of how our country was at the time, and therefore many wanted to make changes to it. An Era of Reform: Many people during the Gilded Age swung into action to reform society – meaning, to change for the better. People who called for reform during this time were called “reformers” Many African Americans, Native Americans, immigrants, and women called for reforms for improved treatment of their communities. The Muckrakers: Some reformers during the Progressive Era were also called muckrakers – who were journalists that helped “dig up dirt” on problems in society and published stories about them in newspapers and magazines. -

Teddy Bear.Pdf

Teddy Bear Question A money box, or piggy bank, often takes the shape of a pig. I can understand this because live pigs used to be a kind of reserve in winter. Whatever was left in terms of food, you gave to your pig. Children’s cuddly toys often have the shape of a bear and even toys with another appearance are often called “teddy bear”. I do not understand why children’s toys often take the form of a bear. What is the reason that children’s toys often take the shape of a bear? Why is this? C. Hilverda, Hurdegaryp Answer Thank you very much for asking your question to the University of Groningen. Such a nice question! We do not have any experts in this specific area, but we can find an answer to your question, though it is not based on scientific proof. We have to go back to 1902, when Theodore Roosevelt was the president of the United States. He went bear hunting, but refused to shoot a bear himself. There are several versions of the story: one story goes that it was a bear cub, another that it was a bear that had been caught, which did not prove to be any challenge to Roosevelt. Not long after, a cartoon appeared in the Washington Post showing Roosevelt as a hunter that refuses to shoot a bear. This bear was to become known as “Teddy’s bear”. These events and the hype surrounding the cartoon were soon picked up by a toymaker from Brooklyn. He invented and created the first toy bears made of plush and sold them as teddy bears. -

Artist Doll & Teddy Bear Newsletter

Susan Quinlan Doll & Teddy Bear Museum Artist Doll & Teddy Bear Newsletter Volume 2, No. 2 September 2017 2018 Quinlan Artist Doll and Teddy Bear Convention The 8th annual Artist Doll and Teddy Bear Convention, otherwise referred to as the “Quinlan Show” by the artist community, will be held again at the Clarion Hotel in Philadelphia on April 12-14, 2018. Registration is not available until November 1. Eventually, all the information about the convention will be at www.quinlanshow.com. We expect there again will be 130 artist sales tables (sellers will all be artists – no dealers/vendors) at the Saturday Conven- tion Show and Sale. The Friday-Saturday convention fee is $195 for artists, collectors and spouses. Those attending Thursday workshops will register directly with the instructor and send them the workshop fee (instructor contact information will be provided). Below is a very preliminary and brief summary of the convention agenda. Thursday, April 12, 2018 • Optional half day and full day workshops (extra fee) • Boot camp indoctrination for first-time attendees • Signature Piece Doll & Teddy Bear Sale & Judging for Bullard/Port Awards • All day free coffee, tea and lemonade • Complimentary wine, beer, and soda open bar • Meals available in private dining room or hotel restaurant (on your own) • Professional photographer service (nominal fee) Friday, April 13, 2018 • Convention begins with Friday breakfast and ends with Saturday banquet • Two collectable rare convention artist souvenir pins • New and old doll and teddy bear magazines