Condition Survey of Aquia Creek Sandstone Columns from the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Stones of Our Nation's Capital

/h\q AaAjnyjspjopiBs / / \ jouami aqi (O^iqiii^eda . -*' ", - t »&? ?:,'. ..-. BUILDING STONES OF OUR NATION'S CAPITAL The U.S. Geological Survey has prepared this publication as an earth science educational tool and as an aid in understanding the history and physi cal development of Washington, D.C., the Nation's Capital. The buildings of our Nation's When choosing a building stone, Capital have been constructed with architects and planners use three char rocks from quarries throughout the acteristics to judge a stone's suitabili United States and many distant lands. ty. It should be pleasing to the eye; it Each building shows important fea should be easy to quarry and work; tures of various stones and the geolog and it should be durable. Today it is ic environment in which they were possible to obtain fine building stone formed. from many parts of the world, but the This booklet describes the source early builders of the city had to rely and appearance of many of the stones on materials from nearby sources. It used in building Washington, D.C. A was simply too difficult and expensive map and a walking tour guide are to move heavy materials like stone included to help you discover before the development of modern Washington's building stones on your transportation methods like trains and own. trucks. Ancient granitic rocks Metamorphosed sedimentary""" and volcanic rocks, chiefly schist and metagraywacke Metamorphic and igneous rocks Sand.gravel, and clay of Tertiary and Cretaceous age Drowned ice-age channel now filled with silt and clay Physiographic Provinces and Geologic and Geographic Features of the District of Columbia region. -

Draft National Mall Plan / Environmental Impact Statement the National Mall

THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT DRAFT NATIONAL MALL PLAN / ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT THE NATIONAL MALL THE MALL CONTENTS: THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................................... 249 Context for Planning and Development of the National Mall ...................................................................251 1790–1850..................................................................................................................................................251 L’Enfant Plan....................................................................................................................................251 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................252 1850–1900..................................................................................................................................................253 The Downing Plan...........................................................................................................................253 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................253 1900–1950..................................................................................................................................................254 The McMillan Plan..........................................................................................................................254 -

Field Trips Guide Book for Photographers Revised 2008 a Publication of the Northern Virginia Alliance of Camera Clubs

Field Trips Guide Book for Photographers Revised 2008 A publication of the Northern Virginia Alliance of Camera Clubs Copyright 2008. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced or copied in any manner whatsoever. 1 Preface This field trips guide book has been written by Dave Carter and Ed Funk of the Northern Virginia Photographic Society, NVPS. Both are experienced and successful field trip organizers. Joseph Miller, NVPS, coordinated the printing and production of this guide book. In our view, field trips can provide an excellent opportunity for camera club members to find new subject matter to photograph, and perhaps even more important, to share with others the love of making pictures. Photography, after all, should be enjoyable. The pleasant experience of an outing together with other photographers in a picturesque setting can be stimulating as well as educational. It is difficullt to consistently arrange successful field trips, particularly if the club's membership is small. We hope this guide book will allow camera club members to become more active and involved in field trip activities. There are four camera clubs that make up the Northern Virginia Alliance of Camera Clubs McLean, Manassas-Warrenton, Northern Virginia and Vienna. All of these clubs are located within 45 minutes or less from each other. It is hoped that each club will be receptive to working together to plan and conduct field trip activities. There is an enormous amount of work to properly arrange and organize many field trips, and we encourage the field trips coordinator at each club to maintain close contact with the coordinators at the other clubs in the Alliance and to invite members of other clubs to join in the field trip. -

Building Stones of the National Mall

The Geological Society of America Field Guide 40 2015 Building stones of the National Mall Richard A. Livingston Materials Science and Engineering Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA Carol A. Grissom Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA Emily M. Aloiz John Milner Associates Preservation, 3200 Lee Highway, Arlington, Virginia 22207, USA ABSTRACT This guide accompanies a walking tour of sites where masonry was employed on or near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It begins with an overview of the geological setting of the city and development of the Mall. Each federal monument or building on the tour is briefly described, followed by information about its exterior stonework. The focus is on masonry buildings of the Smithsonian Institution, which date from 1847 with the inception of construction for the Smithsonian Castle and continue up to completion of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. The building stones on the tour are representative of the development of the Ameri can dimension stone industry with respect to geology, quarrying techniques, and style over more than two centuries. Details are provided for locally quarried stones used for the earliest buildings in the capital, including A quia Creek sandstone (U.S. Capitol and Patent Office Building), Seneca Red sandstone (Smithsonian Castle), Cockeysville Marble (Washington Monument), and Piedmont bedrock (lockkeeper's house). Fol lowing improvement in the transportation system, buildings and monuments were constructed with stones from other regions, including Shelburne Marble from Ver mont, Salem Limestone from Indiana, Holston Limestone from Tennessee, Kasota stone from Minnesota, and a variety of granites from several states. -

Local Arrangements Guide for 2020

SCS/AIA DC-area Local Arrangements Guide Contributors: • Norman Sandridge (co-chair), Howard University • Katherine Wasdin (co-chair), University of Maryland, College Park • Francisco Barrenechea, University of Maryland, College Park • Victoria Pedrick, Georgetown University • Elise Friedland, George Washington University • Brien Garnand, Howard University • Carolivia Herron, Howard University • Sarah Ferrario, Catholic University This guide contains information on the history of the field in the DC area, followed by things to do in the city with kids, restaurants within walking distance of the hotel and convention center, recommended museums, shopping and other entertainment activities, and two classically-themed walking tours of downtown DC. 2 History: In the greater Washington-Baltimore area classics has deep roots both in academics of our area’s colleges and universities and in the culture of both cities. From The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore—with one of the oldest graduate programs in classics in the country to the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, VA, classicists and archaeologists are a proud part of the academic scene, and we take pleasure in inviting you during the SCS and AIA meetings to learn more about the life and heritage of our professions. In Maryland, the University of Maryland at College Park has strong programs and offers graduate degrees in classical languages, ancient history, and ancient philosophy. But classics also flourishes at smaller institutions such as McDaniel College in Westminster, MD, and the Naval Academy in Annapolis. Right in the District of Columbia itself you will find four universities with strong ties to the classics through their undergraduate programs: The Catholic University of America, which also offers a PhD, Howard University, Georgetown University, and The Georgetown Washington University. -

Comments Received

PARKS & OPEN SPACE ELEMENT (DRAFT RELEASE) LIST OF COMMENTS RECEIVED Notes on List of Comments: ⁃ This document lists all comments received on the Draft 2018 Parks & Open Space Element update during the public comment period. ⁃ Comments are listed in the following order o Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions o Comments from Local & Regional Agencies o Comments from Interest Groups o Comments from Interested Individuals Comments from Federal Agencies & Institutions United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE National Capital Region 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. IN REPLY REFER TO: Washington, D.C. 20242 May 14, 2018 Ms. Surina Singh National Capital Planning Commission 401 9th Street, NW, Suite 500N Washington, DC 20004 RE: Comprehensive Plan - Parks and Open Space Element Comments Dear Ms. Singh: Thank you for the opportunity to provide comments on the draft update of the Parks and Open Space Element of the Comprehensive Plan for the National Capital: Federal Elements. The National Park Service (NPS) understands that the Element establishes policies to protect and enhance the many federal parks and open spaces within the National Capital Region and that the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) uses these policies to guide agency actions, including review of projects and preparation of long-range plans. Preservation and management of parks and open space are key to the NPS mission. The National Capital Region of the NPS consists of 40 park units and encompasses approximately 63,000 acres within the District of Columbia (DC), Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia. Our region includes a wide variety of park spaces that range from urban sites, such as the National Mall with all its monuments and Rock Creek Park to vast natural sites like Prince William Forest Park as well as a number of cultural sites like Antietam National Battlefield and Manassas National Battlefield Park. -

Aquia Sandstone in Carlyle House and in Nearby Colonial Virginia by Rosemary Maloney

Carlyle House August, 2012 D OCENT D ISPATC H Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority Aquia Sandstone in Carlyle House and in Nearby Colonial Virginia By Rosemary Maloney John Carlyle wanted to build an imposing home, and he The source of this tan to light-gray sandstone was wanted to build it of stone, like the great stone houses of familiar to the early settlers of Virginia. A quarry England and Scotland. But comparable stone was not was created there as early as 1650. Today, there available in the Atlantic coastal plain of Virginia. For are still ledges exposed on both sides of Interstate Carlyle the only convenient local source of stone hard 95 near Stafford and along Aquia Creek. This enough for building was the sandstone (or freestone as it stone is suitable for building purposes because of was known in colonial times) from the area around the cementation by silica of its components: Aquia Creek in Stafford County, Virginia, about 35 quartz, sand, and pebbles. But Aquia sandstone miles south of Alexandria. The name Aquia is believed has its flaws. It tends to weather unevenly and to be a corruption of the original Algonquin word therefore is more suitable for interior than exterior “Quiyough,” meaning gulls. construction. Construction of Carlyle House In a letter dated November 12, 1752, to his brother George in England, John Carlyle remarks on the difficulty of building his house in Alexandria. But his frustration is blended with optimism as he writes: “...the Violent Rains we have had this Fall, has hurt the Stone Walls that We Was obliged to Take down A part After it Was nigh its Height, which has been A Loss & great disapointment To me, however Time & patience Will over come all (I am In hopes)...” Apart from this single mention of stone walls, nowhere in the letters to George does John mention Aquia sandstone, or how it was quarried and transported. -

Balls Bluff Battlefield National Historic Landmark

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BALL’S BLUFF BATTLEFIELD HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Historic District Other Name/Site Number: VDHR 253-5021 / 053-0012-0005 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Not for publication: X City/Town: Leesburg, Virginia Vicinity: X State: VA County: Loudoun Code: 107 Zip Code: 20176 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: X District: _X_ Public-State: _ X_ Site: ___ Public-Federal: _X _ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 5 115 buildings 11 5 sites 8 24 structures 0 7 objects 24 151 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 10_ 7: Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Historic District (M : 12-46) 2: Catoctin Rural Historic District (VDHR 053-0012) 1: Murray Hill (VDHR 053-5783) Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: The Civil War in Virginia, 1861 – 1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources. NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BALL’S BLUFF BATTLEFIELD HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

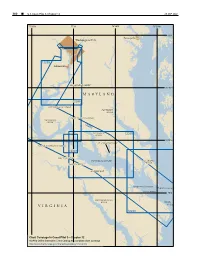

M a R Y L a N D V I R G I N

300 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 26 SEP 2021 77°20'W 77°W 76°40'W 76°20'W 39°N Annapolis Washington D.C. 12289 Alexandria PISCATAWAY CREEK 38°40'N MARYLAND 12288 MATTAWOMAN CREEK PATUXENT RIVER PORT TOBACCO RIVER NANJEMOY CREEK 12285 WICOMICO 12286 RIVER 38°20'N ST. CLEMENTS BAY UPPER MACHODOC CREEK 12287 MATTOX CREEK POTOMAC RIVER ST. MARYS RIVER POPES CREEK NOMINI BAY YEOCOMICO RIVER Point Lookout COAN RIVER 38°N RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER Smith VIRGINIA Point 12233 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 12 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 ¢ 301 Chesapeake Bay, Potomac River (1) This chapter describes the Potomac River and the above the mouth; thence the controlling depth through numerous tributaries that empty into it; included are the dredged cuts is about 18 feet to Hains Point. The Coan, St. Marys, Yeocomico, Wicomico and Anacostia channels are maintained at or near project depths. For Rivers. Also described are the ports of Washington, DC, detailed channel information and minimum depths as and Alexandria and several smaller ports and landings on reported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), these waterways. use NOAA Electronic Navigational Charts. Surveys and (2) channel condition reports are available through a USACE COLREGS Demarcation Lines hydrographic survey website listed in Appendix A. (3) The lines established for Chesapeake Bay are (12) described in 33 CFR 80.510, chapter 2. Anchorages (13) Vessels bound up or down the river anchor anywhere (4) ENCs - US5VA22M, US5VA27M, US5MD41M, near the channel where the bottom is soft; vessels US5MD43M, US5MD44M, US4MD40M, US5MD40M sometimes anchor in Cornfield Harbor or St. -

Washington–Rochambeau Revolutionary Route

Resource Study & Environmental Assessment WASHINGTON–ROCHAMBEAU REVOLUTIONARY ROUTE Northeast and National Capital Regions National Park Service—U.S. Department of the Interior October 2006 ABOUT THIS DOCUMENT This document is the Resource Study and Environmental Assessment (study/EA) for the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route. It describes the National Park Service’s preferred approach to preserving and interpreting route resources and one other alternative. The evaluation of potential environmental impacts that may result from imple- mentation of these alternatives is integrated in this document. This study/EA is available for public review for a period of 30 days. During the review period, the National Park Service is accepting comments from interested parties via the Planning, Environment and Public Comment website http://parkplanning.nps.gov/, at public meetings which may be held, and at the address below. At the end of the re- view period, the National Park Service will carefully review all comments and determine whether any changes should be made to the report. No sooner than thirty (30) days from the end of the review period, the National Park Service will prepare and publish a finding of no significant impact (FONSI) to explain which alternative has been selected, and why it will not have any significant environmental impacts. A summary of responses to public comments will be prepared. Factual corrections or additional material submitted by commentators that do not affect the alternative may be incorporated in errata sheets and attached to the study/EA. The study/EA and FONSI will be transmitted to the Secretary of the Interior who will make a recommendation to Congress. -

Capitol Buildings and Grounds

CAPITOL BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS UNITED STATES CAPITOL OVERVIEW OF THE BUILDING AND ITS FUNCTION The United States Capitol is among the most architecturally impressive and symbolically important buildings in the world. It has housed the meeting chambers of the Senate and the House of Representatives for almost two centuries. Begun in 1793, the Capitol has been built, burnt, rebuilt, extended, and restored; today, it stands as a monument not only to its builders but also to the American people and their government. As the focal point of the government's Legislative Branch, the Capitol is the centerpiece of the Capitol Complex, which includes the six principal Congressional office buildings and three Library of Congress buildings constructed on Capitol Hill in the 19th and 20th centuries. In addition to its active use by Congress, the Capitol is a museum of American art and history. Each year, it is visited by an estimated seven to ten million people from around the world. A fine example of 19th-century neoclassical architecture, the Capitol combines function with aesthetics. Its designs derived from ancient Greece and Rome evoke the ideals that guided the Nation's founders as they framed their new republic. As the building was expanded from its original design, harmony with the existing portions was carefully maintained. Today, the Capitol covers a ground area of 175,170 square feet, or about 4 acres, and has a floor area of approximately 161¤2 acres. Its length, from north to south, is 751 feet 4 inches; its greatest width, including approaches, is 350 feet. Its height above the base line on the east front to the top of the Statue of Freedom is 287 feet 51¤2 inches; from the basement floor to the top of the dome is an ascent of 365 steps. -

Basin Instinct CHERRY BLOSSOMS SPECIAL SECTION: the Trees Have Yet to fl Aunt Their Petals, but Already the Masses Feel the Primal Pull of Spring

A PUBLICATION OF TWP | MARCH 22-24, 2013 | FREE DAILY Basin Instinct CHERRY BLOSSOMS SPECIAL SECTION: The trees have yet to fl aunt their petals, but already the masses feel the primal pull of spring. Join them, won’t you? PAGES 14-25 JOHN S. DYKES/FOR EXPRESS March Madness: Hoyas jump into the fray, plus an NCAA TV guide 10-12 2 | EXPRESS | 03.22.2013 | FRIDAY CHRIS RADBURN/GETTY IMAGES eye openers STICKY FINGERS Police Find Baffled Thieves Stuck to Getaway Vehicles Thieves are illegally tapping maple trees on private property in Maine and stealing sap that is used to make maple syrup. Forest Ranger Jeff Currier says the Maine Forest Service has gotten a dozen complaints from landowners finding taps in their trees with buck- ets or jugs underneath to collect the sap. (AP) PAYING IT FORWARD “We are always on the lookout for ways to recycle.” — KATHY COX, OF DOGS ALOUD, A DOG-GROOMING SALON IN ENGLAND, WHICH IS ENCOURAGING RESIDENTS TO TAKE HAIR FROM THE SALON AND LEAVE IT OUTSIDE THEIR HOMES FOR BIRDS TO MAKE NESTS WITH, THE BLACKPOOL GAZETTE REPORTED THURSDAY REVIEWS ‘That Was the Priciest Bumper-Car Ride Ever’ San Diego police are searching for a couple who crashed a $250,000 Lamborghini only hours after it was purchased. KGTV-TV reported that police were called Monday after witnesses said a 2008 black Lam- borghini Murcielago left Interstate 5 at a high speed ‘KATE NEEDED THE CARRIAGE’ Queen Elizabeth II boards a train Wednesday and crashed; they said a man and woman got out and on her way to Baker Street Underground Station, where she was to mark the 150th ran off.