Milton A. Dickerson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Stones of Our Nation's Capital

/h\q AaAjnyjspjopiBs / / \ jouami aqi (O^iqiii^eda . -*' ", - t »&? ?:,'. ..-. BUILDING STONES OF OUR NATION'S CAPITAL The U.S. Geological Survey has prepared this publication as an earth science educational tool and as an aid in understanding the history and physi cal development of Washington, D.C., the Nation's Capital. The buildings of our Nation's When choosing a building stone, Capital have been constructed with architects and planners use three char rocks from quarries throughout the acteristics to judge a stone's suitabili United States and many distant lands. ty. It should be pleasing to the eye; it Each building shows important fea should be easy to quarry and work; tures of various stones and the geolog and it should be durable. Today it is ic environment in which they were possible to obtain fine building stone formed. from many parts of the world, but the This booklet describes the source early builders of the city had to rely and appearance of many of the stones on materials from nearby sources. It used in building Washington, D.C. A was simply too difficult and expensive map and a walking tour guide are to move heavy materials like stone included to help you discover before the development of modern Washington's building stones on your transportation methods like trains and own. trucks. Ancient granitic rocks Metamorphosed sedimentary""" and volcanic rocks, chiefly schist and metagraywacke Metamorphic and igneous rocks Sand.gravel, and clay of Tertiary and Cretaceous age Drowned ice-age channel now filled with silt and clay Physiographic Provinces and Geologic and Geographic Features of the District of Columbia region. -

Aquia Sandstone in Carlyle House and in Nearby Colonial Virginia by Rosemary Maloney

Carlyle House August, 2012 D OCENT D ISPATC H Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority Aquia Sandstone in Carlyle House and in Nearby Colonial Virginia By Rosemary Maloney John Carlyle wanted to build an imposing home, and he The source of this tan to light-gray sandstone was wanted to build it of stone, like the great stone houses of familiar to the early settlers of Virginia. A quarry England and Scotland. But comparable stone was not was created there as early as 1650. Today, there available in the Atlantic coastal plain of Virginia. For are still ledges exposed on both sides of Interstate Carlyle the only convenient local source of stone hard 95 near Stafford and along Aquia Creek. This enough for building was the sandstone (or freestone as it stone is suitable for building purposes because of was known in colonial times) from the area around the cementation by silica of its components: Aquia Creek in Stafford County, Virginia, about 35 quartz, sand, and pebbles. But Aquia sandstone miles south of Alexandria. The name Aquia is believed has its flaws. It tends to weather unevenly and to be a corruption of the original Algonquin word therefore is more suitable for interior than exterior “Quiyough,” meaning gulls. construction. Construction of Carlyle House In a letter dated November 12, 1752, to his brother George in England, John Carlyle remarks on the difficulty of building his house in Alexandria. But his frustration is blended with optimism as he writes: “...the Violent Rains we have had this Fall, has hurt the Stone Walls that We Was obliged to Take down A part After it Was nigh its Height, which has been A Loss & great disapointment To me, however Time & patience Will over come all (I am In hopes)...” Apart from this single mention of stone walls, nowhere in the letters to George does John mention Aquia sandstone, or how it was quarried and transported. -

Balls Bluff Battlefield National Historic Landmark

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BALL’S BLUFF BATTLEFIELD HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Historic District Other Name/Site Number: VDHR 253-5021 / 053-0012-0005 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Not for publication: X City/Town: Leesburg, Virginia Vicinity: X State: VA County: Loudoun Code: 107 Zip Code: 20176 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: X District: _X_ Public-State: _ X_ Site: ___ Public-Federal: _X _ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 5 115 buildings 11 5 sites 8 24 structures 0 7 objects 24 151 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 10_ 7: Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Historic District (M : 12-46) 2: Catoctin Rural Historic District (VDHR 053-0012) 1: Murray Hill (VDHR 053-5783) Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: The Civil War in Virginia, 1861 – 1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources. NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BALL’S BLUFF BATTLEFIELD HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

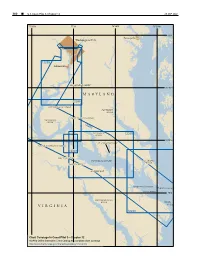

M a R Y L a N D V I R G I N

300 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 26 SEP 2021 77°20'W 77°W 76°40'W 76°20'W 39°N Annapolis Washington D.C. 12289 Alexandria PISCATAWAY CREEK 38°40'N MARYLAND 12288 MATTAWOMAN CREEK PATUXENT RIVER PORT TOBACCO RIVER NANJEMOY CREEK 12285 WICOMICO 12286 RIVER 38°20'N ST. CLEMENTS BAY UPPER MACHODOC CREEK 12287 MATTOX CREEK POTOMAC RIVER ST. MARYS RIVER POPES CREEK NOMINI BAY YEOCOMICO RIVER Point Lookout COAN RIVER 38°N RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER Smith VIRGINIA Point 12233 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 12 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 ¢ 301 Chesapeake Bay, Potomac River (1) This chapter describes the Potomac River and the above the mouth; thence the controlling depth through numerous tributaries that empty into it; included are the dredged cuts is about 18 feet to Hains Point. The Coan, St. Marys, Yeocomico, Wicomico and Anacostia channels are maintained at or near project depths. For Rivers. Also described are the ports of Washington, DC, detailed channel information and minimum depths as and Alexandria and several smaller ports and landings on reported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), these waterways. use NOAA Electronic Navigational Charts. Surveys and (2) channel condition reports are available through a USACE COLREGS Demarcation Lines hydrographic survey website listed in Appendix A. (3) The lines established for Chesapeake Bay are (12) described in 33 CFR 80.510, chapter 2. Anchorages (13) Vessels bound up or down the river anchor anywhere (4) ENCs - US5VA22M, US5VA27M, US5MD41M, near the channel where the bottom is soft; vessels US5MD43M, US5MD44M, US4MD40M, US5MD40M sometimes anchor in Cornfield Harbor or St. -

Potomac Basin Large River Environmental Flow Needs

Potomac Basin Large River Environmental Flow Needs PREPARED BY James Cummins, Claire Buchanan, Carlton Haywood, Heidi Moltz, Adam Griggs The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street Suite PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 R. Christian Jones, Richard Kraus Potomac Environmental Research and Education Center George Mason University 4400 University Drive, MS 5F2 Fairfax, VA 22030-4444 Nathaniel Hitt, Rita Villella Bumgardner U.S. Geological Survey Leetown Science Center Aquatic Ecology Branch 11649 Leetown Road, Kearneysville, WV 25430 PREPARED FOR The Nature Conservancy of Maryland and the District of Columbia 5410 Grosvenor Lane, Ste. 100 Bethesda, MD 20814 WITH FUNDING PROVIDED BY The National Park Service Final Report May 12, 2011 ICPRB Report 10-3 To receive additional copies of this report, please write Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe St., PE-08 Rockville, MD 20852 or call 301-984-1908 Disclaimer This project was made possible through support provided by the National Park Service and The Nature Conservancy, under the terms of their Cooperative Agreement H3392060004, Task Agreement J3992074001, Modifications 002 and 003. The content and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the policy of the National Park Service or The Nature Conservancy and no official endorsement should be inferred. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the opinions or policies of the U. S. Government, or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. Acknowledgments This project was supported by a National Park Service subaward provided by The Nature Conservancy Maryland/DC Office and by the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, an interstate compact river basin commission of the United States Government and the compact's signatories: Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and the District of Columbia. -

Appendix E – Development and Refinement of Hydrologic Model

Appendix E – Development and Refinement of Hydrologic Model Contents Hydrologic modeling efforts for the MPRWA project had multiple components. Detailed descriptions about the hydrologic modeling methodology are provided in the files on the attached disc. The file names listed below are identical to the file names on the disc. Disc Contents Documents (PDF files) AppendixE_HydrologicModel.pdf (74 KB) – this file FutureScenarios_110712.pdf (1,891 KB) Describes the development of the five future scenarios in the CBP HSPF modeling environment. It also spatially presents the resulting hydrologic alteration in seven selected flow metrics. Watershed_delineation_011712.pdf (537 KB) Describes how biological monitoring points were selected from the Chessie BIBI database and, once selected, how the watersheds draining to those locations were delineated. Resegmentation_at_Impoundments_011712.pdf (376 KB) Describes the methodology utilized to re-segment the CBP HSPF model at “significant” impoundments in the study area. Pot-Susq_CART_analysis_011712.pdf (486 KB) Describes how thresholds of flow alteration risk were identified by a CART analysis of the Potomac-Susquehanna dataset of gaged watersheds. Baseline_Landuse_011212.pdf (143 KB) Describes the calculation of land uses in the baseline model scenario. Baseline_Scenario_011212.pdf (580 KB) Describes the development of the baseline scenario in the CBP HSPF modeling environment including the removal of impoundments, withdrawals, and discharges, and conversion of current to baseline land uses. Select results of the baseline scenario are also presented. WOOOMM_Inputs_011012.pdf (525 KB) Describes the inputs needed to establish the ELOHA watersheds in the VADEQ WOOOMM environment and documents how those inputs were developed. Application_of_ModelingTools_011312.pdf (619 KB) Describes the evaluation of the CBP Phase 5 model and VADEQ WOOOMM module for use in the Middle Potomac River Watershed Assessment. -

TNW Report.Pdf

ARCHEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL DETERMINATION OF TRADITIONALLY NAVIGABLE WATERS IN NORTHERN VIRGINIA AND A COMPREHENSIVE METHODOLOGY FOR THE DETERMINATION OF THE TRADITIONAL NAVIGABILITY OF WATERWAYS IN THE UNITED STATES Goose Creek Canal, Loudoun County Virginia William P. Barse, Ph.D. and Boyd Sipe July 2007 5300 Wellington Branch Drive • Suite 100 • Gainesville, VA 20155 • Phone 703.679.5600 • Fax 703.679.5601 www.wetlandstudies.com A Division of Wetland Studies and Solutions, Inc. ABSTRACT This document presents the results of an archival and documentary study on the Traditional Navigability of Waterways in Northern Virginia. The study area is depicted in Attachment 1 of this report and is roughly bounded by the Potomac River on the north and east, the Opequon Creek watershed on the west and the Rappahannock River watershed on the south. The study was conducted by Thunderbird Archeology, a division of Wetland Studies and Solutions, Inc. of Gainesville, Virginia. The purposes of this work are threefold. The primary purpose is to assist consultants and regulators in completing Section III of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Approved Jurisdictional Form. In order to accomplish this goal, a working definition of what constitutes Traditional Navigable Waterways was prepared. This definition will aid in the determination of Waters of the United States jurisdiction for the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers within the study area. Secondly, using specific archeological and historical information, the paper demonstrates that certain rivers and streams can be identifiable as Traditional Navigable Waterways. It is also possible to consider the use of streams for recreation, e.g. -

Potomac Basin Comprehensive Water Resources Plan

One Basin, One Future Potomac River Basin Comprehensive Water Resources Plan Prepared by the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin - 2018 - Dedication i VISION This plan provides a roadmap to achieving our shared vision that the Potomac River basin will serve as a national model for water resources management that fulfills human and ecological needs for current and future generations. The plan will focus on sustainable water resources management that provides the water quantity and quality needed for the protection and enhancement of public health, the environment, all sectors of the economy, and quality of life in the basin. The plan will be based on the best available science and data. The ICPRB will serve as the catalyst for the plan's implementation through an adaptive process in collaboration with partner agencies, institutions, organizations, and the public. Dedication ii DEDICATION This plan is dedicated to Herbert M. Sachs, an ICPRB Maryland Commissioner and Executive Director. He also served for decades with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the Department of the Environment. He passed away in 2017. During his nearly 30-year tenure of service to ICPRB, Sachs led the agency’s efforts in supporting the regional Chesapeake Bay Program; reallocation of water supplies, cooperative law enforcement, and water quality efforts at Jennings Randolph Reservoir; and establishment of the North Brach Potomac Task Force, a group of stakeholders and officials facilitated by ICPRB that gives stakeholders a voice in management decisions. He also was at the helm when ICPRB embarked on its successful effort to restore American shad to the Potomac River. -

Historic Resources Survey Stafford County Virginia

Historic Resources Survey Stafford County Virginia Final Report Prepared BY Traceries With Assistance From P Consulting Services and Preservation Technologies For Stafford County Planning Department and Virginia Department of Historic Resources June 1992 This project could not have been completed without the assistance and support of Stafford County's citizens and members of the Stafford County Planning Department. Several individuals have helped Traceries with this project by providing personal knowledge and information on Stafford County's architecture and history. Jeff O'Dell, Architectural Historian with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, provided overall guidance to Traceries during the survey and encouraged the close examination of Stafford County's agricultural resources. Jeff reviewed our survey forms, photographs and historic context report, and provided helpful comments and suggestions that were incorporated into the final products. Traceries extends special thanks to Kathy Baker and David Grover of the Stafford County Planning Department. Kathy and David and the Planning Department provided Traceries the opportunity to conduct this survey and report, and offered us guidance throughout the project. Kathy and David assisted Traceries in the administrative and research aspects of the survey and supported all of our efforts. Members of the Historical Society and Citizens to Serve Stafford County met with Traceries and helped to answer questions and guide us to historic resources in the county. Mr. and Mrs. John Scott, Barbara Kirby and Ruth Carlone spent time with members of the survey team and provided important insight into the county's history. Mr. George Gordon also met with Traceries to discuss the survey project. -

Potomac River Basin

POTOMAC RIVER BASIN WATERBODY AND AFFECTED AFFECTED LOCALITIES CONTAMINANT SPECIES ADVISORIES/RESTRICTIONS BOUNDARIES Potomac River Basin American Eel (the following tributaries between the VA/MD state line near Rt. 340 bridge (Loudoun County) to the I-395 bridge in Arlington County (above Loudoun Co., the Woodrow Wilson Bridge): Goose Creek up to Fairfax Co., PCBs No more than two meals/month the Dulles Greenway Road Bridge, Broad Run up Arlington Co. to Rt. 625 bridge, Difficult Run up to Rt. 7 bridge, and Pimmit Run up to Rt. 309 bridge. These tributaries comprise ~24 miles) Carp PCBs DO NOT EAT American Eel PCBs DO NOT EAT Channel Catfish ≥ 18 inches PCBs DO NOT EAT Channel Catfish < 18 inches PCBs Potomac River Basin Bullhead Catfish PCBs (the tidal portion of the following tributaries and embayments from I- Largemouth Bass 395 bridge (above the Woodrow Arlington Co, PCBs Wilson Bridge) to the Potomac River Alexandria City, Bridge at Rt. 301: Four Mile Run, Fairfax Co., Anadromous (coastal) Hunting Creek, Little Hunting Creek, Striped Bass Prince William Co., PCBs Pohick Creek, Accotink Creek, Stafford Co., Occoquan River, Neabsco Creek, King George Co. Sunfish Species Powell Creek, Quantico Creek, PCBs Chopawamsic Creek, Aquia Creek, No more than two meals/month and Potomac Creek. These tributaries Smallmouth Bass comprise ~126 miles) PCBs White Catfish PCBs White Perch PCBs Gizzard Shad PCBs Yellow Perch PCBs Gizzard Shad PCBs Potomac River Basin White Perch (the tidal portion of the following tributaries from the Potomac River King George Co., Bridge at Rt. 301 to mouth of river near Westmoreland Co., PCBs No more than two meals/month Smith Point: Upper Machodoc Creek, Northumberland Co. -

TRANSPORTATION Aquia Landing Steamers and Railroads by Jane and Al Conner for Years, the Most Common Mode of Land Transportation

TRANSPORTATION Aquia Landing Steamers and Railroads by Jane and Al Conner For years, the most common mode of land transportation in Stafford County was horse or horse and wagon, or stagecoach. If one wished to travel north it was a long journey which depended upon the weather, as the eastern Chopawamsic Creek area in northern Stafford became a swampy, muddy bog after rain and impeded traffic for weeks. The average trip from Richmond to Washington was thirty-eight hours in duration. The year 1815 brought forth a dramatic change with the emergence of the steamboat. Daily steamboat runs were established from Washington D.C. to Aquia Creek Landing. Aquia Landing became a busy port, as many transfers would disembark and catch a stagecoach and travel south to Richmond. (In 1817, James Madison left Washington, D.C., after his presidency. He and his wife, Dolley, departed the White House, boarded a steamer at the Navy Yard, and traveled to Aquia Landing. There they boarded a carriage for their trip to Montpelier.) Twenty-seven years later, in 1842, another transportation change took place making Aquia Landing an important terminus. The RF&P. Railroad (Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad) had track connecting Richmond to Aquia Landing. This cut the travel time from Washington to Richmond to 9 hours, consisting of a 3 ½ hour steamboat trip from Washington to Aquia Landing and then a 5 ½ hour trip aboard the RF&P to Richmond. During the Civil War, the railroads were taken over by both the Confederates and Union forces. Neither side wanted the other to take control of the area. -

A Study of the Properties of the U.S. Capitol Sandstone

NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS REPORT 4998 A STUDY OP THE PROPERTIES OF THE U.S. CAPITOL SANDSTONE fey Arthur Ho ckTnan and D. W. Kessler Report to the Architect of the Capitol U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Sinclair Weeks, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS A. V. Astin, Director THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The scope of activities of the National Bureau of Standards at its headquarters in Washington, D. C., and its major field laboratories in Boulder, Colorado, is suggested in the following listing of the divisions and sections engaged in technical work. In general, each section carries out spe- cialized research, development, and engineering in the field indicated by its title. A brief description of the activities, and of the resultant reports and publications, appears on the inside back cover of this report. WASHINGTON, D. C. Electricity and Electronics. Resistance and Reactance. Electron Tubes. Electrical Instruments. Magnetic Measurements. Dielectrics. Engineering Electronics. Electronic Instrumentation. Electrochemistry. Optics and Metrology. Photometry and Colorimetry. Optical Instruments. Photographic Technology. Length. Engineering Metrology. Heat and Power. Temperature Physics. Thermodynamics. Cryogenic Physics. Rheology and Lubrication. Engine Fuels. Atomic and Radiation Physics. Spectroscopy. Radiometry. Mass Spectrometry. Solid State Physics. Electron Physics. Atomic Physics. Nuclear Physics. Radioactivity. X-rays. Betatron. Nucleonic Instrumentation. Radiological Equipment. AEC Radiation Instruments. Chemistry. Organic Coatings. Surface Chemistry. Organic Chemistry. Analytical Chemistry. Inorganic Chemistry. Electrodeposition. Gas Chemistry. Physical Chemistry. Thermo- chemistry. Spectrochemistry. Pure Substances. Mechanics. Sound. Mechanical Instruments. Fluid Mechanics. Engineering Mechanics. Mass and Scale. Capacity, Density, and Fluid Meters. Combustion Controls. Organic and Fibrous Materials.