Depleted Uranium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainable Tourism for Rural Lovren, Vojislavka Šatrić and Jelena Development” (2010 – 2012) Beronja Provided Their Contributions Both in English and Serbian

Environment and sustainable rural tourism in four regions of Serbia Southern Banat.Central Serbia.Lower Danube.Eastern Serbia - as they are and as they could be - November 2012, Belgrade, Serbia Impressum PUBLISHER: TRANSLATORS: Th e United Nations Environment Marko Stanojević, Jasna Berić and Jelena Programme (UNEP) and Young Pejić; Researchers of Serbia, under the auspices Prof. Branko Karadžić, Prof. Milica of the joint United Nations programme Jovanović Popović, Violeta Orlović “Sustainable Tourism for Rural Lovren, Vojislavka Šatrić and Jelena Development” (2010 – 2012) Beronja provided their contributions both in English and Serbian. EDITORS: Jelena Beronja, David Owen, PROOFREADING: Aleksandar Petrović, Tanja Petrović Charles Robertson, Clare Ann Zubac, Christine Prickett CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Prof. Branko Karadžić PhD, GRAPHIC PREPARATION, Prof. Milica Jovanović Popović PhD, LAYOUT and DESIGN: Ass. Prof. Vladimir Stojanović PhD, Olivera Petrović Ass. Prof. Dejan Đorđević PhD, Aleksandar Petrović MSc, COVER ILLUSTRATION: David Owen MSc, Manja Lekić Dušica Trnavac, Ivan Svetozarević MA, PRINTED BY: Jelena Beronja, AVANTGUARDE, Beograd Milka Gvozdenović, Sanja Filipović PhD, Date: November 2012. Tanja Petrović, Mesto: Belgrade, Serbia Violeta Orlović Lovren PhD, Vojislavka Šatrić. Th e designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Moreover, the views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations, nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. Acknowledgments Th is publication was developed under the auspices of the United Nations’ joint programme “Sustainable Tourism for Rural Development“, fi nanced by the Kingdom of Spain through the Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund (MDGF). -

Informal Videoconference of Ministers Responsible for Foreign Affairs 14 August

Informal videoconference of Ministers responsible for Foreign Affairs 14 August Participants Belgium: Mr Philippe GOFFIN Minister for Foreign Affairs and Defence Bulgaria: Mr Petko DOYKOV Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Czech Republic: Mr Tomáš PETŘÍČEK Minister for Foreign Affairs Denmark: Mr Jesper MØLLER SØRENSEN State Secretary for Foreign Policy Germany: Mr Heiko MAAS Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs Estonia: Mr Urmas REINSALU Minister for Foreign Affairs Ireland: Mr Derek LAMBE FAC/GAC Attaché Greece: Mr Nikolaos-Georgios DENDIAS Minister for Foreign Affairs Spain: Ms Arancha GONZÁLEZ LAYA Minister for Foreign Affairs, the European Union and Cooperation France: Mr Clément BEAUNE Minister of State with responsibility for European Affairs, attached to the Minister for Europe and for Foreign Affairs Croatia: Mr Gordan GRLIĆ RADMAN Minister for Foreign and European Affairs Italy: Mr Luigi DI MAIO Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation Cyprus: Mr Nikos CHRISTODOULIDES Minister for Foreign Affairs Latvia: Mr Edgars RINKĒVIČS Minister for Foreign Affairs Lithuania: Mr Linas LINKEVIČIUS Minister for Foreign Affairs Luxembourg: Mr Jean ASSELBORN Minister for Foreign and European Affairs, Minister for Immigration and Asylum Hungary: Mr Csaba Sándor BALOGH Minister of State for Administrative Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade Malta: Mr Evarist BARTOLO Minister for Foreign and European Affairs Netherlands: Mr Stef BLOK Minister for Foreign Affairs Austria: Mr Alexander SCHALLENBERG Federal Minister for European and International Affairs Poland: Mr Jacek CZAPUTOWICZ Minister for Foreign Affairs Portugal: Ms Ana Paula ZACARIAS State Secretary for European Affairs Romania: Mr Bogdan Lucian AURESCU Minister for Foreign Affairs Slovenia: Mr Tone KAJZER State Secretary at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Slovakia: Mr Ivan KORČOK Minister for Foreign and European Affairs Finland: Mr Pekka HAAVISTO Minister for Foreign Affairs Sweden: Ms Ann LINDE Minister for Foreign Affairs Commission: Mr Olivér VÁRHELYI Membre . -

Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

Public Disclosure Authorized FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF YUGOSLAVIA BREAKING WITH THE PAST: THE PATH TO STABILITY AND GROWTH Volume II: Assistance Priorities and Public Disclosure Authorized Sectoral Analyses Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS………………………………………………………...viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT……………………………………………………………………….. ix CHAPTER 1. AN OVERVIEW OF THE ECONOMIC RECOVERY AND TRANSITION PROGRAM…………………………………………………………………………………….... 1 A. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..... 1 B. The Government’s medium-term Challenges…………………………………………..... 3 C. Medium-term External Financing Requirements………………………………….……... 4 D. The 2001 Program………………………………………………………………………... 8 E. Implementing the Program………………………………………………………….…....13 CHAPTER 2. FISCAL POLICY AND MANAGEMENT………………….…………………..15 A. Reducing Quasi Fiscal Deficits and Hidden Risks…………………………………….. ..16 B. Transparency and Accountability of Public Spending………………….………………..27 C. Public Debt Management………………………………………………………………...34 D. Tax Policy and Administration…………………………………………….…………... ..39 CHAPTER 3. TRADE………………………………………...…………………….…………..48 A. Patterns of Trade in Goods and Services ……………………………..………..……… ..48 B. Trade Policies: Reforms to date and plans for the future………………………………...51 C. Capacity to Trade: Institutional and other constraints to implementation…………….....55 D. Market Access: The global, European and regional dimension……………………….. ..57 E. Policy recommendations………………………………………………………………....60 F. Donor Program……………………………………………………………….…………..62 -

Assessment of Irrigation Water Quality of Kosovo Plain

Original scientific paper Оригиналан научни рад UDC: 628.1`034.3:631.67 DOI: 10.7251/AGREN1603243R Assessment of Irrigation Water Quality of Kosovo Plain Smajl Rizani1,2, Perparim Laze1,2, Alban Ibraliu1,2 1Agricultural University of Tirana, Faculty of Agriculture and Environment, Albania 2Department of Plant Science and Technology, Tirana, Albania Abstract The study aims to assess the quality of irrigation water of the Kosovo Plain. Twelve water samples were collected from sampling points in the peak of dry season in July 2015. Samples were taken from rivers, canals and pumping stations. The contents of the samples have been analyzed. The classification used to assess qualities and the suitability of irrigation water is based on FAO’s and USSL’s classification criteria of irrigation water. The study revealed that important constituents which influence the quality of irrigation water such as: electrical conductivity, total dissolved solids, sodium adsorption ratio, soluble sodium percentage, residual sodium bicarbonate, permeability index and Kelly’s ratio, were found within the permissible limits of water for irrigation purposes. Therefore, the surface water of this area is deemed to be of an excellent quality and its use is highly recommended for the irrigation of crops. Key words: water, irrigation, quality, classification, assessment Agro-knowledge Journal, vol. 17, no. 3, 2016, 243-253 243 Introduction The quality of the irrigation water may affect both crop yields and soil physical conditions, even if all other conditions and cultural practices are optimal (FAO, 1985). Irrigation waters whether derived from springs, diverted from streams, or pumped from wells, contain appreciable quantities of chemical substances in solution that may reduce crop yield and deteriorate soil fertility. -

Law and Military Operations in Kosovo: 1999-2001, Lessons Learned For

LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS IN KOSOVO: 1999-2001 LESSONS LEARNED FOR JUDGE ADVOCATES Center for Law and Military Operations (CLAMO) The Judge Advocate General’s School United States Army Charlottesville, Virginia CENTER FOR LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS (CLAMO) Director COL David E. Graham Deputy Director LTC Stuart W. Risch Director, Domestic Operational Law (vacant) Director, Training & Support CPT Alton L. (Larry) Gwaltney, III Marine Representative Maj Cody M. Weston, USMC Advanced Operational Law Studies Fellows MAJ Keith E. Puls MAJ Daniel G. Jordan Automation Technician Mr. Ben R. Morgan Training Centers LTC Richard M. Whitaker Battle Command Training Program LTC James W. Herring Battle Command Training Program MAJ Phillip W. Jussell Battle Command Training Program CPT Michael L. Roberts Combat Maneuver Training Center MAJ Michael P. Ryan Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Peter R. Hayden Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Mark D. Matthews Joint Readiness Training Center SFC Michael A. Pascua Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Jonathan Howard National Training Center CPT Charles J. Kovats National Training Center Contact the Center The Center’s mission is to examine legal issues that arise during all phases of military operations and to devise training and resource strategies for addressing those issues. It seeks to fulfill this mission in five ways. First, it is the central repository within The Judge Advocate General's Corps for all-source data, information, memoranda, after-action materials and lessons learned pertaining to legal support to operations, foreign and domestic. Second, it supports judge advocates by analyzing all data and information, developing lessons learned across all military legal disciplines, and by disseminating these lessons learned and other operational information to the Army, Marine Corps, and Joint communities through publications, instruction, training, and databases accessible to operational forces, world-wide. -

BULGARIA and HUNGARY in the FIRST WORLD WAR: a VIEW from the 21ST CENTURY 21St -Century Studies in Humanities

BULGARIA AND HUNGARY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR: A VIEW FROM THE 21ST CENTURY 21st -Century Studies in Humanities Editor: Pál Fodor Research Centre for the Humanities Budapest–Sofia, 2020 BULGARIA AND HUNGARY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR: A VIEW FROM THE 21ST CENTURY Editors GÁBOR DEMETER CSABA KATONA PENKA PEYKOVSKA Research Centre for the Humanities Budapest–Sofia, 2020 Technical editor: Judit Lakatos Language editor: David Robert Evans Translated by: Jason Vincz, Bálint Radó, Péter Szőnyi, and Gábor Demeter Lectored by László Bíró (HAS RCH, senior research fellow) The volume was supported by theBulgarian–Hungarian History Commission and realized within the framework of the project entitled “Peripheries of Empires and Nation States in the 17th–20th Century Central and Southeast Europe. Power, Institutions, Society, Adaptation”. Supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences NKFI-EPR K 113004, East-Central European Nationalisms During the First World War NKFI FK 128 978 Knowledge, Lanscape, Nation and Empire ISBN: 978-963-416-198-1 (Institute of History – Research Center for the Humanities) ISBN: 978-954-2903-36-9 (Institute for Historical Studies – BAS) HU ISSN 2630-8827 Cover: “A Momentary View of Europe”. German caricature propaganda map, 1915. Published by the Research Centre for the Humanities Responsible editor: Pál Fodor Prepress preparation: Institute of History, RCH, Research Assistance Team Leader: Éva Kovács Cover design: Bence Marafkó Page layout: Bence Marafkó Printed in Hungary by Prime Rate Kft., Budapest CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................... 9 Zoltán Oszkár Szőts and Gábor Demeter THE CAUSES OF THE OUTBREAK OF WORLD WAR I AND THEIR REPRESENTATION IN SERBIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY .................................. 25 Krisztián Csaplár-Degovics ISTVÁN TISZA’S POLICY TOWARDS THE GERMAN ALLIANCE AND AGAINST GERMAN INFLUENCE IN THE YEARS OF THE GREAT WAR................................ -

Подкласс Exogenia Collin, 1912

Research Article ISSN 2336-9744 (online) | ISSN 2337-0173 (print) The journal is available on line at www.ecol-mne.com Contribution to the knowledge of distribution of Colubrid snakes in Serbia LJILJANA TOMOVIĆ1,2,4*, ALEKSANDAR UROŠEVIĆ2,4, RASTKO AJTIĆ3,4, IMRE KRIZMANIĆ1, ALEKSANDAR SIMOVIĆ4, NENAD LABUS5, DANKO JOVIĆ6, MILIVOJ KRSTIĆ4, SONJA ĐORĐEVIĆ1,4, MARKO ANĐELKOVIĆ2,4, ANA GOLUBOVIĆ1,4 & GEORG DŽUKIĆ2 1 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Biology, Studentski trg 16, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 2 University of Belgrade, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, Bulevar despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 3 Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia, Dr Ivana Ribara 91, 11070 Belgrade, Serbia 4 Serbian Herpetological Society “Milutin Radovanović”, Bulevar despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 5 University of Priština, Faculty of Science and Mathematics, Biology Department, Lole Ribara 29, 38220 Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia 6 Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia, Vožda Karađorđa 14, 18000 Niš, Serbia *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Received 28 March 2015 │ Accepted 31 March 2015 │ Published online 6 April 2015. Abstract Detailed distribution pattern of colubrid snakes in Serbia is still inadequately described, despite the long historical study. In this paper, we provide accurate distribution of seven species, with previously published and newly accumulated faunistic records compiled. Comparative analysis of faunas among all Balkan countries showed that Serbian colubrid fauna is among the most distinct (together with faunas of Slovenia and Romania), due to small number of species. Zoogeographic analysis showed high chorotype diversity of Serbian colubrids: seven species belong to six chorotypes. South-eastern Serbia (Pčinja River valley) is characterized by the presence of all colubrid species inhabiting our country, and deserves the highest conservation status at the national level. -

Skanderbeg's Activity During the Period of 1443 – 1448

History Research 2021; 9(1): 49-57 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/history doi: 10.11648/j.history.20210901.16 ISSN: 2376-6700 (Print); ISSN: 2376-6719 (Online) Skanderbeg's Activity During the Period of 1443 – 1448 Bedri Muhadri Department of the Medieval History, Institution of History “Ali Hadri”, Prishtina, Kosovo Email address: To cite this article: Bedri Muhadri. Skanderbeg's Activity During the Period of 1443 – 1448. History Research. Vol. 9, No. 1, 2021, pp. 49-57. doi: 10.11648/j.history.20210901.16 Received : December 17, 2020; Accepted : January 29, 2021; Published : March 3, 2021 Abstract: The period of 1443-1448 marks the first step of the unification of many Albanian territories, under the leadership of Gjergj Kastriot-Skanderbeg, for the overall organization to fight the Ottoman invader and the usurper, the Republic of Venice. This union was realized with the Assembly of Lezha on March 2 of 1444 with the participation of all the Albanian princes, where the appropriate institutions were formed in the overall political and military organization of the country. Skanderbeg was appointed as commander and leader of the League of Lezha and Commander of the Arber Army. In such commitments the country was united politically and economically in the interest of realisation of a liberation war. In its beginnings the League of Lezha achieved great success by expelling Ottoman invaders in a number of cities and the headquarters of the League of Lezha became Kruja, the seat of the Kastriots. In an effort to preserve the territorial integrity of the country and to create preconditions for the country's economic development, the Lezha League headed by Skanderbeg had to go into war with the Republic of Venice, as a result of the Venetian occupation of the city of Deja, this war ended with the peace signed on 4 October of 1448. -

20202605 ENG Programme for Participants FINAL

Version – 26 May 2020 INTERNATIONAL DONORS CONFERENCE IN SOLIDARITY WITH VENEZUELAN REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS IN THE COUNTRIES OF THE REGION AMID COVID-19 VIDEOCONFERENCE PROGRAMME 26th MAY 2020 (Subjected to minor changes upon technical issues) Link to streaming in Youtube https://youtu.be/SSzGpNaazoo Contact numbers (+34) 661 664 152 (Spanishl) (+34) 676 181 797 (Spanish and English) (+34) 687 294 878 (Spanish and English) (+34) 657 494 199 (Spanish and English) Contact e-mail To: [email protected] CC: [email protected] Connexion 14:00-15:45 Delegations connect and test their links to the videoconference 15:45 All delegations should be connected to the videoconference room. Welcome 16:00 Minister for Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation of the Kingdom of Spain, Arancha González Laya. (3 mins) 16:03 High Representative and Vice-President of the European Commission, Josep Borrell. (3 mins) 16:06 Welcome by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, António Guterres (video) 16:08 UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi. 16:11 Director-General of the International Organization for Migration, Antonio Vitorino. 1 Version – 26 May 2020 16:14 Update from the RMRP by Eduardo Stein, Special Joint Representative IOM/UNHCR for the Venezuelan refugees and migrants. HOST COUNTRIES • 3 minutes interventions • Order of intervention: By protocol ranK and if ranK is equal then by number of Venezuelan refugees and migrants hosted in the country. 16:17 Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Colombia, Claudia Blum. 16:20 Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Peru, Gustavo Meza-Cuadra. -

(1389) and the Munich Agreement (1938) As Political Myths

Department of Political and Economic Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Helsinki The Battle Backwards A Comparative Study of the Battle of Kosovo Polje (1389) and the Munich Agreement (1938) as Political Myths Brendan Humphreys ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in hall XII, University main building, Fabianinkatu 33, on 13 December 2013, at noon. Helsinki 2013 Publications of the Department of Political and Economic Studies 12 (2013) Political History © Brendan Humphreys Cover: Riikka Hyypiä Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISSN-L 2243-3635 ISSN 2243-3635 (Print) ISSN 2243-3643 (Online) ISBN 978-952-10-9084-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-9085-1 (PDF) Unigrafia, Helsinki 2013 We continue the battle We continue it backwards Vasko Popa, Worriors of the Field of the Blackbird A whole volume could well be written on the myths of modern man, on the mythologies camouflaged in the plays that he enjoys, in the books that he reads. The cinema, that “dream factory” takes over and employs countless mythical motifs – the fight between hero and monster, initiatory combats and ordeals, paradigmatic figures and images (the maiden, the hero, the paradisiacal landscape, hell and do on). Even reading includes a mythological function, only because it replaces the recitation of myths in archaic societies and the oral literature that still lives in the rural communities of Europe, but particularly because, through reading, the modern man succeeds in obtaining an ‘escape from time’ comparable to the ‘emergence from time’ effected by myths. -

Kosovo Field Trip Study Report

Kosovo – from theory of human rights protection and monitoring to the complex realities on the ground By Güler Alkan, student representative What was our Kosovo field trip about and what did we learn from the experience on the ground? Was it a "journey" into a post-conflict country, a "tour" of international organizations, a great opportunity to talk to top-level diplomats and politicians, both national and international ones, and to hear from civil society and local NGOs? It was all of that and even more. The list of organizations, speakers and venues is too long to name them all – from the headquarters of UNMIK, EULEX or the OSCE mission in Pristina to visits to the Kosovo Assembly or official bodies like the Kosovo Judicial Centre as well as meetings with representatives from local NGOs, media and oppositional politicians. Every speaker was very eager to answer our questions – from the Minister of Trade and Industry, Mimoza Kusari-Lila, to Igballe Rogova, the founder of Kosovo Women's Network who shared with us her personal experiences and the daily struggle for women's and LGBT rights in Kosovo, to Albin Kurti, a political activist with whom we discussed lively about issues of self-determination, about how far one can go when protesting on the streets and about the limits of authorities repressing street protests. Our Kosovo trip went beyond purely academic or legal matters. We gained invaluable insights into the various dimensions of human rights issues in a post-conflict environment . We realized that establishing a functioning rule of law system is not only about adopting laws but also about the implementation of the provisions and the challenges faced in practice. -

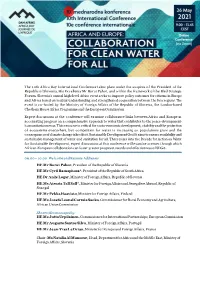

10Th Africa Day International Conference

The 10th Africa Day International Conference takes place under the auspices of the President of the Republic of Slovenia, His Excellency Mr Borut Pahor, and within the framework of the Bled Strategic Forum. Slovenia’s annual high-level Africa event seeks to improve policy outcomes for citizens in Europe and Africa based on mutual understanding and strengthened cooperation between the two regions. The event is co-hosted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Slovenia, the London-based Chatham House Africa Programme and the European Commission. Expert discussions at the conference will examine collaborative links between Africa and Europe in accelerating progress on a comprehensive approach to water that contributes to the peace-development- humanitarian nexus. This resource is critical for socio-economic development, stability and the protection of ecosystems everywhere, but competition for water is increasing as populations grow and the consequences of climate change take effect. Sustainable Development Goal 6 aims to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. Three years into the Decade for Action on Water for Sustainable Development, expert discussions at this conference will examine avenues through which African-European collaboration can foster greater progress towards and effectiveness of SDG 6. 09.00 – 10.00 Welcome and Keynote Addresses HE Mr Borut Pahor, President of the Republic of Slovenia HE Mr Cyril Ramaphosa*, President of the Republic of South Africa HE Dr Anže Logar, Minister