X Block 1.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merry Wives (Edited 2019)

!1 The Marry Wives of Windsor ACT I SCENE I. Windsor. Before PAGE's house. BLOCK I Enter SHALLOW, SLENDER, and SIR HUGH EVANS SHALLOW Sir Hugh, persuade me not; I will make a Star-chamber matter of it: if he were twenty Sir John Falstaffs, he shall not abuse Robert Shallow, esquire. SIR HUGH EVANS If Sir John Falstaff have committed disparagements unto you, I am of the church, and will be glad to do my benevolence to make atonements and compremises between you. SHALLOW Ha! o' my life, if I were young again, the sword should end it. SIR HUGH EVANS It is petter that friends is the sword, and end it: and there is also another device in my prain, there is Anne Page, which is daughter to Master Thomas Page, which is pretty virginity. SLENDER Mistress Anne Page? She has brown hair, and speaks small like a woman. SIR HUGH EVANS It is that fery person for all the orld, and seven hundred pounds of moneys, is hers, when she is seventeen years old: it were a goot motion if we leave our pribbles and prabbles, and desire a marriage between Master Abraham and Mistress Anne Page. SLENDER Did her grandsire leave her seven hundred pound? SIR HUGH EVANS Ay, and her father is make her a petter penny. SHALLOW I know the young gentlewoman; she has good gifts. SIR HUGH EVANS Seven hundred pounds and possibilities is goot gifts. Enter PAGE SHALLOW Well, let us see honest Master Page. PAGE I am glad to see your worships well. -

Merry Wives of Windsor

The Merry Wives of Windsor by William Shakespeare Presented by Paul W. Collins © Copyright 2012 by Paul W. Collins The Merry Wives of Windsor By William Shakespeare Presented by Paul W. Collins All rights reserved under the International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this work may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, audio or video recording, or other, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Contact: [email protected] Note: Spoken lines from Shakespeare’s drama are in the public domain, as is the Globe edition (1864) of his plays, which provided the basic text of the speeches in this new version of The Merry Wives of Windsor. But The Merry Wives of Windsor, by William Shakespeare: Presented by Paul W. Collins is a copyrighted work, and is made available for your personal use only, in reading and study. Student, beware: This is a presentation, not a scholarly work, so you should be sure your teacher, instructor or professor considers it acceptable as a reference before quoting characters’ comments or thoughts from it in your report or term paper. 2 Chapter One Confrontations aiting outside George Page’s stately Windsor home this fine sunny morning is Hugh W Evans, a kindly Welsh cleric. The parson hopes to resolve a complaint being made by the visiting uncle of a parishioner. “Sir Hugh, persuade me not,” insists the wizened old man, a veteran of the war, and now one of the keepers of the king’s grounds. -

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Fat, Disreputable Sir John Falstaff Pursues Two Housewives, Mistress Ford and Mistress Page, Who Outwit and Humiliate Him Instead

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Get even more from the Folger You can get your own copy of this text to keep. Purchase a full copy to get the text, plus explanatory notes, illustrations, and more. Buy a copy Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 1 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 1 ACT 2 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 3 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 ACT 4 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 6 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 5 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. -

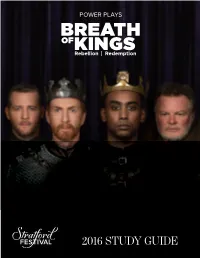

2016 Study Guide

2016 STUDY ProductionGUIDE Sponsor 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER BREATH OF KINGS: REBELLION | REDEMPTION BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE CONCEIVED AND ADAPTED BY GRAHAM ABBEY WORLD PREMIÈRE COMMISSIONED BY THE STRATFORD FESTIVAL DIRECTORS MITCHELL CUSHMAN AND WEYNI MENGESHA TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by The Brian Linehan Charitable Foundation and by Martie & Bob Sachs INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: From left: Graham Abbey, Tom Rooney, Araya Mengesha, Geraint Wyn Davies.. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis .............................................................................................................. -

Henry V Booklet

William Shakespeare Henry V with Samuel West • Timothy West • Cathy Sara and full cast CLASSIC DRAMA NA320512D 1 Prologue Enter Chorus CHORUS: O for a muse of fire… 3:09 2 Act I Scene 1 An antechamber in King Henry’s palace Enter the two Bishops of Canterbury and Ely CANTERBURY: My lord, I’ll tell you, that self bill is urged… 4:48 3 Act I Scene 2 The council chamber in King Henry’s palace Enter the King, Gloucester, Bedford, Clarence, Westmorland and Exeter and attendants KING: Where is my gracious lord of Canterbury? 8:59 4 Act I Scene 2 (cont.) CANTERBURY: Therefore doth heaven divide… 2:41 5 Act I Scene 2 (cont.) Enter Ambassador of France (with attendants) KING: Now are we well prepared to know the pleasure 5:08 6 Act II Enter Chorus CHORUS: Now all the youth of England are on fire… 2:04 2 7 Act II Scene 1 London. The Boar’s Head tavern Enter Corporal Nym and Lieutenant Bardolph BARDOLPH: Well met, Corporal Nym6:42 8 Act II Scene 2 Southampton Enter Exeter, Bedford and Westmorland BEDFORD: ‘Fore God, his grace is bold to trust these traitors. 3:47 9 Act II Scene 2 (cont.) KING: The mercy that was quick in us… 7:00 10 Act II Scene 3 London. The Boar’s Head tavern Enter Pistol, Nym, Bardolph, Boy and Hostess HOSTESS: Prithee, honey-sweet husband, let me bring thee to Staines. 0:33 11 Act II Scene 3 HOSTESS: Nay he’s not in hell. He’s in Arthur’s bosom… 3:21 12 Act II Scene 4 France. -

The Life of King Henry the Fifth. Edited by Herbert Arthur Evans

@- THE ARDEN SHAKESPEARE GENERAL EDITOR : W. J. CRAIG THE LIFE OF KING HENRY THE FIFTH THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE LIFE OF KING HENRY THE FIFTH EDITED BY HERBERT ARTHUR EVANS ? ^^C:<^ METHUEN AND CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON Second Edition /f/7 CONTENTS _ PAGB Introduction -^^ The Life of King Henry the Fifth . i Appendix ^ vfi First Published . Octobir 33rd igoj Seccmd Edition . /g/7 INTRODUCTION — Connexion of Henry V. with the preceding Histories, p. ix Its first on the and in xi — xiv—The appearance stage print, p. —Date, p. Quarto text and its relation—to the Foho, p. xvii Henry V. and the Fatnous Victories^ p. xxv Shakespeare's conception of Henry's xxxi—Conduct of the action and function of the character, p. Chorus,— p. xli —Supposed allusions to contemporary politics, p. xliii This Edition, p. xlvii. The emergence of the historical drama during the last decade of Elizabeth's reign, and the popularity which it achieved during its brief existence, were the natural out- come of the consciousness of national unity and national greatness to which England was then awakening. Haunted for more than a quarter of a century by the constant dread of foreign invasion and domestic treachery, the country could at last breathe freely, and the fervid patriotism which now animated every order in the State found appropriate " " expression in a noble and solid curiosity to learn the story of the nation's past. Of this curiosity the theatres, then as always the reflection of the popular taste, were not slow to take advantage. -

Vol. 13, No. 6 November 2004

Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promena Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembran Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Ga Salut d'Amour • Mot d'AmourElgar • Bizarrerie Society • O Happy Eyes • My Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenad Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda Snow • Fly, Singing ournalBird • From the Bavarian Highlands • The L Life • King Olaf • Imperial March • The Banner of St George • Te and Benedictus • Caractacus • Variations on an Original T (Enigma) • Sea Pictures • Chanson de Nuit • Chanson de Matin • Characteristic Pieces • The Dream of Gerontius • Serenade Ly Pomp and Circumstance • Cockaigne (In London Town) • C Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May Song • Dream Chil Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • Skizze • Offertoire Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduction and Allegro • Ev Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wand of Youth • How Calm Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine • Elegy • Violin Concer minor • Romance • Symphony No 2 • O Hearken Thou • Coro March • Crown of India • Great is the Lord • Cantique • The Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • Sospiri • The Birthright • The Win • Death on the Hills • Give Unto the Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Un dans le Desert • The Starlight Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The of England • The Fringes of the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • Sonata in E minorNOVEMBER • String Quartet 2004 in E Vol.13,minor •No Piano.6 Quint minor • Cello Concerto in E minor • King Arthur • The Wand E i M h Th H ld B -

Toxic Masculinity in Henry V

The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research Volume 21 Article 2 2020 Toxic Masculinity in Henry V Abigail King [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation King, Abigail. "Toxic Masculinity in Henry V." The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research 21 (2020): -. Web. [date of access]. <https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol21/iss1/2>. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/ur/vol21/iss1/2 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Toxic Masculinity in Henry V Abstract Toxic masculinity motivates the characters and plot of Henry V by William Shakespeare. The play revolves around King Henry V and how he is a model leader of England during the Hundred Years War. Henry uses what a “true” man should be to inspire his soldiers when morale is low. Further, manlihood is seen in the characters or lack thereof. Characters that fail to follow the high expectations of masculinity are killed. Audience members recognize the importance of masculinity throughout the play, although the outcomes of those stereotypes are dangerous seen in the superficial friendships and suppression of authentic self. Keywords toxic masculinity, Shakespeare, friendship Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank Dr. Deborah Uman for encouraging me to submit my work and always helping me develop my writing. -

9 King Henry V Ap 98

Play: King Henry V Author: Shakespeare Text used: New Cambridge Library ref: Key: enter from within enter from without exit inwards Exit outwards Act door Entering door Space-time indication Commentary /sc IN characters OUT and notes I.o Chorus CHOR. O for a muse of fire... (1) Entrance from the high status door? Chorus CHOR. Admit me Chorus to this history...(32) I.i Canterbury, CANT. My lord, I’ll tell you, that They enter together deep in Ely self bill is urged...(1) conversation. Canterbury, CANT. The French ambassador Despite the reference to going ‘in’ Ely upon that instant Craved audi- to the court to hear the embassy, ence, and the hour I think is this is a loop scene, a prelude to come To give him hearing. Is it their entry from outwards into the four o’clock? court of the next scene. ELY. It is. CANT. Then go we in, to know his embassy...(91-5) I.ii King, KING. Where is my gracious lord The court is brought ‘out’ onto the Gloucester, of Canterbury? stage (throne set, etc.) prior to the Bedford, EXETER. Not here in presence. audience with the ambassador. Clarence, KING. Send for him, good uncle. Westmorland, WEST. Shall we call in th’am- Exeter etc. bassador, my liege? (1-3) Canterbury, CANT. God and his angels guard They now return to the stage, Ely your sacred throne...(7) coming in to the court. Attendant KING. Call in the messengers sent from the Dauphin. (221) Ambassador, KING. ...Now are we well prepared Attendant returns from outwards etc. -

The Merry Wives of Windsor

William Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor Kingsmen Shakespeare Festival Summer 2019 PROLOGUE The characters interact in a montage-like scene 1m1 We hear a jaunty score not unlike the opening of a situation comedy, which eventually leads us into the scene 1 minute ACT 1 Scene 1 The Windsor Resort; a delightful vacation retreat which may remind some of similar resorts in the Catskills. The kind of place where Jerry Orbach might have taken his family on vacation. Enter SHALLOW, SLENDER, who have just finished a round of Golf, and SIR HUGH EVANS who, apparently has been notoriously wronged SHALLOW Sir Hugh, persuade me not; I will make a Star- chamber matter of it: if he were twenty Sir John Falstaffs, he shall not abuse Robert Shallow, esquire. SLENDER In the county of Gloucester; justice of peace. SHALLOW Ay, cousin Slender, and 'Custalourum. SLENDER Ay, and 'Rato-lorum' too; and a gentleman born, master parson; who writes himself… SIR HUGH EVANS If Sir John Falstaff hath committed disparagements unto you, I am of the church, and will be glad to do my benevolence to make atonements and compremises between you. SHALLOW The council shall bear it; it is a riot. SIR HUGH EVANS It is not meet the council hear a riot; there is no 1 fear of Got in a riot. SHALLOW Ha! o' my life, if I were young again, the sword should end it. SIR HUGH EVANS It is petter that friends is the sword, and end it: and there is also another device in my prain, which peradventure prings goot discretions with it: there is Anne Page, which is daughter to Master Thomas Page, which is pretty virginity. -

Henry the Fifth. a Historical Play in Five Acts

PR 2812 M2 N5 Zopy 2 \^a' DE WITT'S ACTING- PLAYS. (Number 180.) HENRY THE FIFTH. A HISTOBICAL FLAT, IN FIVE ACTS. By WILLIAM. SHAKSPEARE. AS PEODTJCED AT BOOTH'S THEATRE, NEW YORK, FEB. 8,1875. WITH NOTES UPON ITS A HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE PLAY, REMARKS AND CHARACTERS AND INCIDENTS, AND A COMPLETE DESCRIP- TION OF THE COSTUMES, PROPRRTIES, STAGE BUSINESS AND SCENERY. Kedited, and abkangkd fob kepkesestation, by CHARLES E. NEWTON, (C. E. PEEINE ), Love in Author of ''Out at Sea,' ''Cast upon the Worldrj' Italy;' ''AIL her own Fault,' "A Chapter of Mis- takes;' "Le Pavilion Rouge;' etc., etc. TO WHICH AKE ADDED, -Cast of the Characters A description (»f the Costumes—Synopsis of the Piece —Entrances and Exits -Relative Positions of the Performers on the Stage, and the whole of the Stage Business. • • RT M. DE WITT, PUBLISHER, No. 33 Hose Street. OUT AT SEA. A Drama. In a Prologue and Four Acts. By Charles NOW J E. Newton. Price 15 cents. A BREACH OF PROMISE, A Comic Drama. In Two Acts. By JRJEADT. I T. W. Robertson. Price 15 cents. DE WITT'S HALF-DIME MUSIC OP THE BEST SONGS FOR VOICE AND PIANO. }HIS 8E(RlE8 of first class Songs contains the Words and Music {with the Piano accompaniment) of the most choice and exquisite Pieces, by the most able^ gifted and most popular composers. It contains every style of good Music—from the solemn and pathetic to the light and humorous. In brief this collection is a complete Musical Library in itself both of Vocal AND Piano-Forte Music. -

Shakespeare As a Military Critic

The Open Court Volume XLII (No. 5) MAY, 1928 Number 864 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Frontispiece— IVilUam Shakespeare Shakespeare as a Military Critic, geo. h. daugherty, jr '257 The Philosophy of Meh Ti. quentin kuie yuan huang 277 Jestts and Gotama. carlyle summerbell 290 Insanity, Relafiz'ity, and Group-Formation, thomas d. eliut..303 The Future of Religion in Asia, daljit singh sadharia 315 Published monthly by THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY ZZ7 East Chicago Avenue Chicago, Illinois Subscription rates : $2.00 a year ; 20c a copy. Remittances may be made by personal checks, drafts, post-office or express money orders, payable to the Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago. While the publishers do not hold themselves responsible for manu- scripts sent to them, they endeavor to use the greatest care in returning those not found available, if postage is sent. As a precaution against loss, mistakes, or delay, they request that the name and address of the author be placed at the head of every manuscript (and not on a separate slip) and that all manuscripts and correspondence concerning them be addressed to the Open Court Publishing Company and not to individuals. Address all correspondence to the Open Court Publishing Company, 337 East Chicago Ave., Chicago. Entered as Second-Class matter March 26, 1897, at the Post Office at Chicago, Illinois, under Act of March 3, 1879. Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Company, 1928. Printed in the United States of .America. PHILOSOPHY TODAY A collection of Essays by Outstanding Philosophers of Europe and America Describing the Leading Tendencies in the Various Fields of Contemporary Philosophy.