Redeeming Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Iv, Parts One &

HENRY IV, PARTS ONE & TWO by William Shakespeare Taken together, Shakespeare's major history plays cover the 30-year War of the Roses, a struggle between two great families, descended from King Edward III, for the throne of England. The division begins in “Richard II,” when that king, of the House of York, is deposed by Henry Bolingbroke of the House of Lancaster, who will become Henry IV. The two Henry IV plays take us through this king's reign, ending with the coronation of his ne'er-do-well son, Prince Hal, as Henry V. In subsequent plays, we follow the fortunes of these two families as first one, then the other, assumes the throne, culminating in “Richard III,” which ends with the victory of Henry VII, who ends the War of the Roses by combining both royal lines into the House of Tudor and ruthlessly killing off all claimants to the throne. What gives the Henry IV plays their great appeal is the presence of a fat, rascally knight named Falstaff, with whom Prince Hal spends his youth. Falstaff is one of Shakespeare's most memorable characters and his comedy tends to dominate the action. He was so popular with audiences that Shakespeare had to kill him off in “Henry V,” lest he detract from the heroism of young King Henry V. “Henry IV, Part One,” deals with a rebellion against King Henry by his former allies. The subplot concerns the idle life led by the heir to the throne, Prince Hal, who spends his time with London's riffraff, even going so far as to join them in robbery. -

Merry Wives (Edited 2019)

!1 The Marry Wives of Windsor ACT I SCENE I. Windsor. Before PAGE's house. BLOCK I Enter SHALLOW, SLENDER, and SIR HUGH EVANS SHALLOW Sir Hugh, persuade me not; I will make a Star-chamber matter of it: if he were twenty Sir John Falstaffs, he shall not abuse Robert Shallow, esquire. SIR HUGH EVANS If Sir John Falstaff have committed disparagements unto you, I am of the church, and will be glad to do my benevolence to make atonements and compremises between you. SHALLOW Ha! o' my life, if I were young again, the sword should end it. SIR HUGH EVANS It is petter that friends is the sword, and end it: and there is also another device in my prain, there is Anne Page, which is daughter to Master Thomas Page, which is pretty virginity. SLENDER Mistress Anne Page? She has brown hair, and speaks small like a woman. SIR HUGH EVANS It is that fery person for all the orld, and seven hundred pounds of moneys, is hers, when she is seventeen years old: it were a goot motion if we leave our pribbles and prabbles, and desire a marriage between Master Abraham and Mistress Anne Page. SLENDER Did her grandsire leave her seven hundred pound? SIR HUGH EVANS Ay, and her father is make her a petter penny. SHALLOW I know the young gentlewoman; she has good gifts. SIR HUGH EVANS Seven hundred pounds and possibilities is goot gifts. Enter PAGE SHALLOW Well, let us see honest Master Page. PAGE I am glad to see your worships well. -

Henry IV, Part 2, Continues the Story of Henry IV, Part I

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Get even more from the Folger You can get your own copy of this text to keep. Purchase a full copy to get the text, plus explanatory notes, illustrations, and more. Buy a copy Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play Induction Scene 1 ACT 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 2 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 1 ACT 3 Scene 2 Scene 1 ACT 4 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 5 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 Epilogue From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. -

X Block 1.P65

ENG-02-X (1) Institute of Distance and Open Learning Gauhati University MA in English Semester 2 Paper X Drama I Block 1 Shakespeare’s Contemporaries Contents: Block Introduction: Unit 1 : General Introduction to English Renaissance Drama Unit 2 : Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta Unit 3 : Ben Jonson’s Volpone (1) Contributors: Dr. Aparna Bhattacharya Associate Professor, Dept. of English (Units 1 & 2) Gauhati University Biswajit Saikia Gauhati University (Unit 3) Editorial Team Dr. Asha Kuthari Choudhury Associate Professor, Dept. of English Gauhati University Dr. Uttara Debi Asst. Professor in English IDOL, GU Prasenjit Das Asst. Professor in English KKHSOU, Guwahati Sanghamitra De Lecturer in English IDOL, GU Manab Medhi Lecturer in English IDOL, GU Cover Page Designing: Kaushik Sarma : Graphic Designer CET, IITG February, 2011 © Institute of Distance and Open Learning, Gauhati University. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the Institute of Distance and Open Learning, Gauhati University. Further information about the Institute of Distance and Open Learning, Gauhati University courses may be obtained from the University's office at IDOL Building, Gauhati University, Guwahati-14. Published on behalf of the Institute of Distance and Open Learning, Gauhati University by Dr. Kandarpa Das, Director and printed at Maliyata Offset Press, Mirza. Copies printed 1000. Acknowledgement The Institute of Distance and Open Learning, Gauhati University duly acknowledges the financial assistance from the Distance Education Council, IGNOU, New Delhi, for preparation of this material. (2) Block Introduction: This block is entitled "Shakespeare's Contemporaries" which refers you clearly to the Elizabethan period in English literary history. -

Merry Wives of Windsor

The Merry Wives of Windsor by William Shakespeare Presented by Paul W. Collins © Copyright 2012 by Paul W. Collins The Merry Wives of Windsor By William Shakespeare Presented by Paul W. Collins All rights reserved under the International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this work may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, audio or video recording, or other, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Contact: [email protected] Note: Spoken lines from Shakespeare’s drama are in the public domain, as is the Globe edition (1864) of his plays, which provided the basic text of the speeches in this new version of The Merry Wives of Windsor. But The Merry Wives of Windsor, by William Shakespeare: Presented by Paul W. Collins is a copyrighted work, and is made available for your personal use only, in reading and study. Student, beware: This is a presentation, not a scholarly work, so you should be sure your teacher, instructor or professor considers it acceptable as a reference before quoting characters’ comments or thoughts from it in your report or term paper. 2 Chapter One Confrontations aiting outside George Page’s stately Windsor home this fine sunny morning is Hugh W Evans, a kindly Welsh cleric. The parson hopes to resolve a complaint being made by the visiting uncle of a parishioner. “Sir Hugh, persuade me not,” insists the wizened old man, a veteran of the war, and now one of the keepers of the king’s grounds. -

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Fat, Disreputable Sir John Falstaff Pursues Two Housewives, Mistress Ford and Mistress Page, Who Outwit and Humiliate Him Instead

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Get even more from the Folger You can get your own copy of this text to keep. Purchase a full copy to get the text, plus explanatory notes, illustrations, and more. Buy a copy Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 1 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 1 ACT 2 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 3 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 ACT 4 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 6 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 5 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. -

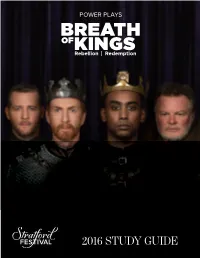

2016 Study Guide

2016 STUDY ProductionGUIDE Sponsor 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER BREATH OF KINGS: REBELLION | REDEMPTION BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE CONCEIVED AND ADAPTED BY GRAHAM ABBEY WORLD PREMIÈRE COMMISSIONED BY THE STRATFORD FESTIVAL DIRECTORS MITCHELL CUSHMAN AND WEYNI MENGESHA TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by The Brian Linehan Charitable Foundation and by Martie & Bob Sachs INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: From left: Graham Abbey, Tom Rooney, Araya Mengesha, Geraint Wyn Davies.. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis .............................................................................................................. -

Henry V Booklet

William Shakespeare Henry V with Samuel West • Timothy West • Cathy Sara and full cast CLASSIC DRAMA NA320512D 1 Prologue Enter Chorus CHORUS: O for a muse of fire… 3:09 2 Act I Scene 1 An antechamber in King Henry’s palace Enter the two Bishops of Canterbury and Ely CANTERBURY: My lord, I’ll tell you, that self bill is urged… 4:48 3 Act I Scene 2 The council chamber in King Henry’s palace Enter the King, Gloucester, Bedford, Clarence, Westmorland and Exeter and attendants KING: Where is my gracious lord of Canterbury? 8:59 4 Act I Scene 2 (cont.) CANTERBURY: Therefore doth heaven divide… 2:41 5 Act I Scene 2 (cont.) Enter Ambassador of France (with attendants) KING: Now are we well prepared to know the pleasure 5:08 6 Act II Enter Chorus CHORUS: Now all the youth of England are on fire… 2:04 2 7 Act II Scene 1 London. The Boar’s Head tavern Enter Corporal Nym and Lieutenant Bardolph BARDOLPH: Well met, Corporal Nym6:42 8 Act II Scene 2 Southampton Enter Exeter, Bedford and Westmorland BEDFORD: ‘Fore God, his grace is bold to trust these traitors. 3:47 9 Act II Scene 2 (cont.) KING: The mercy that was quick in us… 7:00 10 Act II Scene 3 London. The Boar’s Head tavern Enter Pistol, Nym, Bardolph, Boy and Hostess HOSTESS: Prithee, honey-sweet husband, let me bring thee to Staines. 0:33 11 Act II Scene 3 HOSTESS: Nay he’s not in hell. He’s in Arthur’s bosom… 3:21 12 Act II Scene 4 France. -

The Life of King Henry the Fifth. Edited by Herbert Arthur Evans

@- THE ARDEN SHAKESPEARE GENERAL EDITOR : W. J. CRAIG THE LIFE OF KING HENRY THE FIFTH THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE LIFE OF KING HENRY THE FIFTH EDITED BY HERBERT ARTHUR EVANS ? ^^C:<^ METHUEN AND CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON Second Edition /f/7 CONTENTS _ PAGB Introduction -^^ The Life of King Henry the Fifth . i Appendix ^ vfi First Published . Octobir 33rd igoj Seccmd Edition . /g/7 INTRODUCTION — Connexion of Henry V. with the preceding Histories, p. ix Its first on the and in xi — xiv—The appearance stage print, p. —Date, p. Quarto text and its relation—to the Foho, p. xvii Henry V. and the Fatnous Victories^ p. xxv Shakespeare's conception of Henry's xxxi—Conduct of the action and function of the character, p. Chorus,— p. xli —Supposed allusions to contemporary politics, p. xliii This Edition, p. xlvii. The emergence of the historical drama during the last decade of Elizabeth's reign, and the popularity which it achieved during its brief existence, were the natural out- come of the consciousness of national unity and national greatness to which England was then awakening. Haunted for more than a quarter of a century by the constant dread of foreign invasion and domestic treachery, the country could at last breathe freely, and the fervid patriotism which now animated every order in the State found appropriate " " expression in a noble and solid curiosity to learn the story of the nation's past. Of this curiosity the theatres, then as always the reflection of the popular taste, were not slow to take advantage. -

Shakespeare's Widows of a Certain

Working Papers in the Humanities Shakespeare’s Widows of a Certain Age: Celibacy and Economics Dorothea Faith Kehler San Diego State University Abstract Often more honoured in the breach than the observance, the prevailing discourse of early modern England encouraged widows to live as celibates, to epitomize piety, and to devote themselves to safeguarding their children’s interests. Of these injunctions, celibacy was crucial. Among Shakespeare’s elderly widows, all but Mistress Quickly remain single, a condition most vehemently prescribed by Catholic writers, who reluctantly exempted only the youngest widows— prejudged as concupiscent by virtue of their nubility and gender. In print, if not practice, Catholics and Protestants alike appeared to regard celibacy as the only suitable state for older widows. My paper briefly considers five widows of a certain age: Mistress Quickly, who violates the injunction when, between Henry IV, Part 2 and Henry V, she weds Ancient Pistol; Paulina of The Winter’s Tale who, by the end of Act V, has not formally accepted Camillo as a substitute for Antigonus; and the celibate, child-focused widows of Coriolanus and All’s Well That Ends Well, ‘widows indeed’. Whether these characters remarry or remain celibate depends, to a significant extent, on their financial situations, those with greater economic needs remarrying if they can. Although neglected as a category, widows are prominent in Shakespeare’s plays, appearing in every genre. Including ‘seeming widows’—wives uncertain of their marital status like -

The Interpretive Power of Context, Or Why Henry V’S “St

The Interpretive Power of Context, or Why Henry V’s “St. Crispin’s Day” Monologue is Bullshit TYE LANDELS In his short book On Bullshit (2005), Harry Frankfurt develops an analytic theory of bullshit. Bullshit, as defined by Frankfurt, has two definitive conditions. First, its claims are neither deliberatively true nor false. As Frankfurt notes, “[the bullshitter’s] intention is neither to report the truth nor conceal it” (55). Second, its claims attempt to “convey a certain impression” (18) of the speaker. My paper will dis- cuss the ways in which Frankfurt’s definition of bullshit informs an understanding of Henry’s “St. Crispin’s Day” monologue in Shake- speare’s Henry V. I will argue that Henry’s language in this mono- logue satisfies Frankfurt’s definition of bullshit insofar as it conveys an intentional impression of Henry that is neither deliberatively honest nor false. Moreover, I will argue that the extra-dramatic au- dience’s omnispective1 knowledge of Henry’s internal motivations and self-consciousness and the play’s subplot provides neces- sary context within which to identify this monologue as bullshit. Henry’s “St. Crispin’s Day” monologue is a clear act of bullshit, albeit a successful one. In this monologue, Henry notorious- ly appeals to abstract notions of “honor” (Shakespeare 4.3.28) and brotherhood (4.3.60). He constructs two hypothetical scenarios: in the first, he states that, if any soldier “hath no stomach for this fight, / Let him depart; his passport shall be made / And crowns for convoy put into his purse” (4.3.35-37). -

Vol. 13, No. 6 November 2004

Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promena Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembran Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Ga Salut d'Amour • Mot d'AmourElgar • Bizarrerie Society • O Happy Eyes • My Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenad Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda Snow • Fly, Singing ournalBird • From the Bavarian Highlands • The L Life • King Olaf • Imperial March • The Banner of St George • Te and Benedictus • Caractacus • Variations on an Original T (Enigma) • Sea Pictures • Chanson de Nuit • Chanson de Matin • Characteristic Pieces • The Dream of Gerontius • Serenade Ly Pomp and Circumstance • Cockaigne (In London Town) • C Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May Song • Dream Chil Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • Skizze • Offertoire Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduction and Allegro • Ev Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wand of Youth • How Calm Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine • Elegy • Violin Concer minor • Romance • Symphony No 2 • O Hearken Thou • Coro March • Crown of India • Great is the Lord • Cantique • The Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • Sospiri • The Birthright • The Win • Death on the Hills • Give Unto the Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Un dans le Desert • The Starlight Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The of England • The Fringes of the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • Sonata in E minorNOVEMBER • String Quartet 2004 in E Vol.13,minor •No Piano.6 Quint minor • Cello Concerto in E minor • King Arthur • The Wand E i M h Th H ld B