Painting Women Phillippy, Patricia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01-2017 Index Good Short Total Song 1 36 0 36 LOUISA JOHNSON

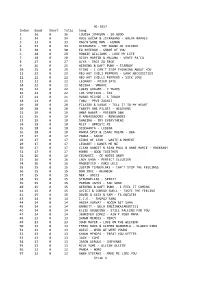

01-2017 Index Good Short Total Song 1 36 0 36 LOUISA JOHNSON - SO GOOD 2 34 0 34 RUDI BUČAR & ISTRABAND - GREVA NAPREJ 3 33 0 33 RAG'N'BONE MAN - HUMAN 4 33 0 33 DISTURBED - THE SOUND OF SILENCE 5 30 0 30 ED SHEERAN - SHAPE OF YOU 6 28 0 28 ROBBIE WILLIAMS - LOVE MY LIFE 7 28 0 28 RICKY MARTIN & MALUMA - VENTE PA'CA 8 27 0 27 ALYA - SRCE ZA SRCE 9 26 0 26 WEEKEND & DAFT PUNK - STARBOY 10 25 0 25 STING - I CAN'T STOP THINKING ABOUT YOU 11 23 0 23 RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS - DARK NECESSITIES 12 22 0 22 RED HOT CHILLI PEPPERS - SICK LOVE 13 22 0 22 LEONART - POJEM ZATE 14 22 0 22 NEISHA - VRHOVI 15 22 0 22 LUKAS GRAHAM - 7 YEARS 16 22 0 22 LOS VENTILOS - ČAS 17 21 0 21 RUSKO RICHIE - S TOBOM 18 21 0 21 TABU - PRVI ZADNJI 19 20 0 20 FILATOV & KARAS - TELL IT TO MY HEART 20 20 0 20 TWENTY ONE PILOTS - HEATHENS 21 19 0 19 OMAR NABER - POSEBEN DAN 22 19 0 19 X AMBASSADORS - RENEGADES 23 19 0 19 SHAKIRA - TRY EVERYTHING 24 18 0 18 NIET - OPROSTI MI 25 18 0 18 SIDDHARTA - LEDENA 26 18 0 18 MANCA ŠPIK & ISAAC PALMA - OBA 27 17 0 17 PANDA - SANJE 28 17 0 17 KINGS OF LEON - WASTE A MOMENT 29 17 0 17 LEONART - DANES ME NI 30 17 0 17 CLEAN BANDIT & SEAN PAUL & ANNE MARIE - ROCKBABY 31 17 0 17 HONNE - GOOD TOGETHER 32 16 0 16 ČEDAHUČI - ČE HOČEŠ GREM 33 16 0 16 LADY GAGA - PERFECT ILLUSION 34 16 0 16 MAGNIFICO - KUKU LELE 35 15 0 15 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE - CAN'T STOP THE FEELINGS 36 15 0 15 BON JOVI - REUNION 37 15 0 15 NEK - UNICI 38 15 0 15 STRUMBELLAS - SPIRIT 39 15 0 15 PARSON JAMES - SAD SONG 40 15 0 15 WEEKEND & DAFT PUNK - I FEEL IT COMING 41 15 0 15 AVIICI & CONRAD SWELL - TASTE THE FEELING 42 15 0 15 DAVID & ALEX & SAM - TA OBČUTEK 43 14 0 14 I.C.E. -

The Masterpieces of Titian; Sixty Reproductions of Photographs From

COWANS S ART BOOKS 6*mT THE MASTERPIECES O T0 LONDON O GLASGOW, GOWANS & QRAY, L m From the Library of Frank Simpson « Telegraphic Address Telephone No. ** GALERADA, 1117, LONDON.” MAYFAIR. CLAUDE & TREVELYAN, THE CARLTON GALLERY, PALL MALL PLACE, LONDON, S,W* PURCHASERS AND SELLERS OF FINE PICTURES BY THE BEST OLD MASTERS. Messrs. CLAUDE & TREVELYAN also invite the attention of anyone desiring Portraits painted in Pastel, to the works of Mr. E. F. Wells, the clever painter of Portraits in Pastel. Attention is also directed to the work of Mr. Hubert Coop and Mr. Gregory Robinson, exceptionally clevet painters of Marine and Landscape Pictures in Oil and Water Colour, and to the exceedingly fine Portraits of Horses by Mr. Lynwood Palmer. Pictures and Engravings Cleaned and Restored. Valuations made for Probate or otherwise. Collections Classified and Arranged, CREAT CONTINENTAL SUCCESSES No. 1 KARL . HEINRICH The Original of the Play OLD HEIDELBERG Which has been acted with such very great success by Mr. George Alexander. By W. MEYER-FORSTER. WITH 12 ILLUSTRATIONS. THE ONLY TRANSLATION. Cloth, 3/6 Net. GOWANS & GRAY, Ltd., London and Glasgow. m Is Its* mmt ksfamssSteg Sites is lU^ws&shsr® t® *M mfe» ®»fe to Bwy ©r S^J Q0IUIKE ANTIQUES. FREE TO CONNOISSEURS «y hxssiRATEfi Catalogue Goods Purchased mmen Returnable if Disapproved* Sm&M Items seal oe appro, to satisfactory applicants. S©S Ev®r-clsaftg1f!g Pieees of ©Id gteina, &sd P&ttmy siwaye an feanS, The , . Connoisseur tre&fM ®n elf euBl«efs (ntensfing fo Coffttefor® mb persont #f culture. HE articles are written fey T acknowledged experts, and are illustrated fey unique photographs mtd drawings of ha* portaat examples a»d collections fro® every part of the world. -

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

Elisabetta Sirani Dipinti Devozionali E “Quadretti Da Letto” Di Una Virtuosa Del Pennello

Temporary exhibition from the storage. LISABETTA E IRANI DipintiS devozionali e “quadretti da letto” di una virtuosa del pennello Palazzo Pepoli Campogrande 18 september - 25 november 2018 Elisabetta Sirani Dipinti devozionali e “quadretti da letto” di una virtuosa del pennello The concept of the exhibition is linked to an important recovery realized by the Nucleo Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale of Bologna: the finding on the antique market, thanks to the advisory of the Pinacoteca, of a small painting with a Virgin praying attributed to the well-known Bolognese painter Elisabetta Sirani (Bologna 1638-1665), whose disappearance has been denounced by Enrico Mauceri in 1930. The restitution of the work to the Pinacoteca and its presentation to the public is accompanied by an exposition of some paintings of Elisabetta, usually kept into the museum storage, with the others normally showed in the gallery (Saint Anthony of Padua adoring Christ Child) and in Palazzo Pepoli Elisabetta Sirani, Virgin praying, Campogrande (Saint Mary Magdalene and Saint Jerome). canvas, cm 46x36, Inv. 625 The aim of this intimate exhibition is to ce- lebrate Elisabetta Sirani as one of the most representative personalities of the Bolognese School in the XVII century, who followed the artistic lesson of the divine Guido Reni. Actually, Elisabetta was not directly a student of Reni, who died when she was four years old. First of four kids, she learnt from her father Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who was direct student of Guido. We can imagine how much the collection of Reni’s drawings kept by Giovanni inspired our young painter, who started to practise in a short while. -

Descriptive Catalogue of the Bowdoin College Art Collections

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Museum of Art Collection Catalogues Museum of Art 1895 Descriptive Catalogue of the Bowdoin College Art Collections Bowdoin College. Museum of Art Henry Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/art-museum-collection- catalogs Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bowdoin College. Museum of Art and Johnson, Henry, "Descriptive Catalogue of the Bowdoin College Art Collections" (1895). Museum of Art Collection Catalogues. 11. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/art-museum-collection-catalogs/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum of Art at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Museum of Art Collection Catalogues by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOWDOIN COLLEGE Desgriptive Catalogue OF THE Art Collections DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGUE OF THE BOWDOIN COLLEGE ART COLLECTIONS BY HENRY JOHNSON, Curator BRUNSWICK, ME. 1895 PUBLISHED BY THE COLLEGE. PRINTED AT JOURNAL OFFICE, LEWISTON, ME. Historical Introduction. The Honorable James Bowdoin, only son of the emi- nent statesman and patriot, Governor James Bowdoin of Massachusetts, returned to this country in 1809 from Europe, where he had been engaged in important diplomatic missions for the United States government. His death occurred in 1811. He bequeathed to the College, besides his library and other valuable property, his collection of paintings, seventy in number, brought together chiefly in Europe, and two portfolios of drawings. The drawings were received by Mr. John Abbot, the agent of the College, December 3, 1811, along with the library, of which they were reckoned a part. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Anti-Makeup: Learning a Bi-Level Adversarial Network for Makeup

Anti-Makeup: Learning A Bi-Level Adversarial Network for Makeup-Invariant Face Verification Yi Li, Lingxiao Song, Xiang Wu, Ran He∗, and Tieniu Tan National Laboratory of Pattern Recognition, CASIA Center for Research on Intelligent Perception and Computing, CASIA Center for Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology, CAS University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China [email protected], flingxiao.song, rhe, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Makeup is widely used to improve facial attractiveness and is well accepted by the public. However, different makeup styles will result in significant facial appearance changes. It remains a challenging problem to match makeup and non-makeup face images. This paper proposes a learning from generation approach for makeup-invariant face verification by introduc- ing a bi-level adversarial network (BLAN). To alleviate the negative effects from makeup, we first generate non-makeup images from makeup ones, and then use the synthesized non- makeup images for further verification. Two adversarial net- works in BLAN are integrated in an end-to-end deep net- work, with the one on pixel level for reconstructing appeal- ing facial images and the other on feature level for preserv- ing identity information. These two networks jointly reduce Figure 1: Samples of facial images with (the first and the the sensing gap between makeup and non-makeup images. third columns) and without (the second and the fourth Moreover, we make the generator well constrained by incor- columns) the application of cosmetics. The significant dis- porating multiple perceptual losses. Experimental results on crepancy of the same identity can be observed. -

ELISABETTA SIRANI's JUDITH with the HEAD of HOLOFERNES By

ELISABETTA SIRANI’S JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES by JESSICA COLE RUBINSKI (Under the Direction of Shelley Zuraw) ABSTRACT This thesis examines the life and artistic career of the female artist, Elisabetta Sirani. The paper focuses on her unparalleled depictions of heroines, especially her Judith with the Head of Holofernes. By tracing the iconography of Judith from masters of the Renaissance into the mid- seventeenth century, it is evident that Elisabetta’s painting from 1658 is unique as it portrays Judith in her ultimate triumph. Furthermore, an emphasis is placed on the relationship between Elisabetta’s Judith and three of Guido Reni’s Judith images in terms of their visual resemblances, as well as their symbolic similarities through the incorporation of a starry sky and crescent moon. INDEX WORDS: Elisabetta Sirani, Judith, Holofernes, heroines, Timoclea, Giovanni Andrea Sirani, Guido Reni, female artists, Italian Baroque, Bologna ELISABETTA SIRANI’S JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES by JESSICA COLE RUBINSKI B.A., Florida State University, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 © 2008 Jessica Cole Rubinski All Rights Reserved ELISABETTA SIRANI’S JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES by JESSICA COLE RUBINSKI Major Professor: Dr. Shelley Zuraw Committee: Dr. Isabelle Wallace Dr. Asen Kirin Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2008 iv To my Family especially To my Mother, Pamela v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank Robert Henson of Carolina Day School for introducing me to the study of Art History, and the professors at Florida State University for continuing to spark my interest and curiosity for the subject. -

Makeup's Effects on Self-Perception

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons OTS Master's Level Projects & Papers STEM Education & Professional Studies 2010 Makeup's Effects on Self-Perception Lauren Silverio Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/ots_masters_projects Recommended Citation Silverio, Lauren, "Makeup's Effects on Self-Perception" (2010). OTS Master's Level Projects & Papers. 49. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/ots_masters_projects/49 This Master's Project is brought to you for free and open access by the STEM Education & Professional Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in OTS Master's Level Projects & Papers by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAKEUP’S EFFECTS ON SELF-PERCEPTION A Research Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Occupational and Technical Studies At Old Dominion University In Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Occupational and Technical Studies By Lauren A. Silverio September 2009 SIGNATURE PAGE This research paper was prepared by Lauren A. Silverio under the direction of Dr. John M. Ritz in OTED 636, Problems in Occupational and Technical Education. It was submitted to the Graduate Program Director as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Occupational and Technical Studies. Approved by: _____________________________ __________________ Dr. John M. Ritz Date Graduate Program Director Occupation and Technical Studies Old Dominion University i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SIGNATURE PAGE…………………………………………………………………… i LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………… iv CHAPTERS I. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………. 1 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM ……………………………… 2 RESEARCH GOALS …………………………………………….. 2 BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE ………………………… 2 LIMITATIONS ……………………………………………………. -

The Eleven Caesars Sample Question Paper

Oxford Cambridge and RSA A Level Ancient History H407/22 The Eleven Caesars Sample Question Paper Date – Morning/Afternoon Time allowed: 2 hours 30 minutes You must have: the OCR 12-page Answer Booklet (OCR12 sent with general stationery) Other materials required: None INSTRUCTIONS Use black ink. Complete the boxes on the front of the Answer Booklet. There are two sections in this paper: Section A and Section B. In Section A, answer Question 1 or 2 and Question 3. In Section B, answer Question 4 and Question 5 or 6. Write the number of each question clearly in the margin. Additional paper may beSPECIMEN used if required but you must clearly show your candidate number, centre number and question number(s). Do not write in the bar codes. INFORMATION The total mark for this paper is 98. The marks for each question are shown in brackets [ ]. Quality of extended response will be assessed in questions marked with an asterisk (*) This document consists of 4 pages. © OCR 2016 H407/22 Turn over 603/0805/9 C10056/3.0 2 Section A: The Julio-Claudian Emperors, 31 BC–AD 68 Answer either question 1 or question 2 and then question 3. Answer either question 1 or question 2. 1* To what extent was there discontent with the emperors during this period? You must use and analyse the ancient sources you have studied as well as your own knowledge to support your answer. [30] 2* How important a role did imperial women play during the reigns of Claudius and Nero? You must use and analyse the ancient sources you have studied as well as your own knowledge to support your answer. -

Rethinking Savoldo's Magdalenes

Rethinking Savoldo’s Magdalenes: A “Muddle of the Maries”?1 Charlotte Nichols The luminously veiled women in Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo’s four Magdalene paintings—one of which resides at the Getty Museum—have consistently been identified by scholars as Mary Magdalene near Christ’s tomb on Easter morning. Yet these physically and emotionally self- contained figures are atypical representations of her in the early Cinquecento, when she is most often seen either as an exuberant observer of the Resurrection in scenes of the Noli me tangere or as a worldly penitent in half-length. A reconsideration of the pictures in connection with myriad early Christian, Byzantine, and Italian accounts of the Passion and devotional imagery suggests that Savoldo responded in an inventive way to a millennium-old discussion about the roles of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene as the first witnesses of the risen Christ. The design, color, and positioning of the veil, which dominates the painted surface of the respective Magdalenes, encode layers of meaning explicated by textual and visual comparison; taken together they allow an alternate Marian interpretation of the presumed Magdalene figure’s biblical identity. At the expense of iconic clarity, the painter whom Giorgio Vasari described as “capriccioso e sofistico” appears to have created a multivalent image precisely in order to communicate the conflicting accounts in sacred and hagiographic texts, as well as the intellectual appeal of deliberately ambiguous, at times aporetic subject matter to northern Italian patrons in the sixteenth century.2 The Magdalenes: description, provenance, and subject The format of Savoldo’s Magdalenes is arresting, dominated by a silken waterfall of fabric that communicates both protective enclosure and luxuriant tactility (Figs. -

Musica Sanat Corpus Per Animam': Towar Tu Erstanding of the Use of Music

`Musica sanat corpus per animam': Towar tU erstanding of the Use of Music in Responseto Plague, 1350-1600 Christopher Brian Macklin Doctor of Philosophy University of York Department of Music Submitted March 2008 BEST COPY AVAILABLE Variable print quality 2 Abstract In recent decadesthe study of the relationship between the human species and other forms of life has ceased to be an exclusive concern of biologists and doctors and, as a result, has provided an increasingly valuable perspective on many aspectsof cultural and social history. Until now, however, these efforts have not extended to the field of music, and so the present study representsan initial attempt to understand the use of music in Werrn Europe's responseto epidemic plague from the beginning of the Black Death to the end of the sixteenth century. This involved an initial investigation of the description of sound in the earliest plague chronicles, and an identification of features of plague epidemics which had the potential to affect music-making (such as its geographical scope, recurrence of epidemics, and physical symptoms). The musical record from 1350-1600 was then examined for pieces which were conceivably written or performed during plague epidemics. While over sixty such pieces were found, only a small minority bore indications of specific liturgical use in time of plague. Rather, the majority of pieces (largely settings of the hymn Stella coeli extirpavit and of Italian laude whose diffusion was facilitated by the Franciscan order) hinted at a use of music in the everyday life of the laity which only occasionally resulted in the production of notated musical scores.