Leiden University the Use of a Football Club As a Means of State Branding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AS Saint-Etienne

AS Saint-Etienne - Werder Bremen MATCH PRESS KIT Geoffroy-Guichard, Saint-Etienne Wednesday 18 March 2009 - 20.30CET (20.30 local time) Matchday 9 - Round of 16, second leg Contents 1 - Match background 6 - Competition facts 2 - Squad list 7 - Team facts 3 - Match officials 8 - Competition information 4 - Domestic information 9 - Legend 5 - Match-by-match lineups This press kit includes information relating to this UEFA Cup match. For more detailed factual information, and in-depth competition statistics, please refer to the matchweek press kit, which can be downloaded at: http://www.uefa.com/uefa/mediaservices/presskits/index.html Match background Despite dealing AS Saint-Etienne their first UEFA competition defeat since November 1982 in the first leg at the Weserstadion, Werder Bremen know that their UEFA Cup Round of 16 tie is far from over. • Having knocked out AC Milan in the previous round, Bremen made a bright start against St-Etienne, with Naldo putting them into a 20th-minute lead, but they failed to increase their advantage after that and head to France with the outcome still in the balance. • St-Etienne had been unbeaten in their 12 previous European games since losing 4-0 at FC Bohemians Praha in the second leg of their 1982/83 UEFA Cup second-round tie on 3 November 1982. That run comprised seven wins and five draws. • Les Verts' nine-game unbeaten home run in Europe stretches back to the quarter-finals of the 1980/81 UEFA Cup, when a team featuring UEFA President Michel Platini lost 4-1 to Ipswich Town FC at the Stade Geoffroy-Guichard. -

Chapter 2 Economic Model of a Professional Football Club in France

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository Chapter 2 Economic model of a professional football club in France Nicolas Scelles and Wladimir Andreff The economic model of football clubs is a revenue model but also a cost model in relation to their objective. It can be defined as the search for balance between revenues, costs and objective, and the latter can vary: profit maximization, sporting maximization under strict constraint (“hard” constraint), or “soft” budget constraint (Andreff, 2009). In France, the revenue model of football clubs has evolved with time. This mutation fits in the switch from an SSSL (Spectators-Subventions-Sponsors- Local) model to an MMMMG (Media-Magnats-Merchandising-Markets-Global) model at the European level (Andreff & Staudohar, 2000). Before 1914, sport financing came mainly from practitioners (Bourg et Gouguet, 2001, p. 19). Thereafter, with competitions as spectacle, spectators have become the primary source of revenue, ahead of the subsidies granted by the local authorities and industry patrons. Advertising revenues have gradually become more and more important and, in the 1960s and 1970s, sponsorship increased significantly as firms were seeking more direct identification in terms of audience, image, reputation and sales (Andreff et Staudohar, 2000, p. 259) . In France, during the 1970s, operating revenues of first division football clubs came mainly from the spectators, supplemented by subsidies and sponsorship. The SSSL model was at its peak, with its “L” finding its justification in the fact that the revenues were generated from local or national residents. The 1980s is the starting point of a continuous increase in the share of TV rights income for French clubs. -

Download the App Now

The magazine of the League Managers Association Issue 10: Winter 2011 £7.50 “Having a strong spirit is essential” M ART IN O ’ N EI LL Ossie Ardiles WHAT DO Aidy Boothroyd LEADERS DO? The big question... Herbert Chapman asked and answered Terry Connor Roy Keane SECOND IN Matt Lorenzo COMMAND Mark McGhee The assistant Gary Speed manager’s role revealed BOXING CLEVER Team The changing face of the TV rights market Issue 10 spirited : Winter 2011 Martin O’Neill on learning from Clough, the art of team building and the challenges ahead SPONSORED BY We’ve created an oil SO STRONG WE HAD TO ENGINEER THE TESTS TO PROVE IT. ENGINEERED WITH Today’s engines work harder, run hotter and operate under higher pressures, to demand maximum performance in these conditions you need a strong oil. That’s why we engineered Castrol EDGE, with new Fluid Strength Technology™. Proven in testing to minimise metal to metal contact, maximising engine performance and always ready to adapt wherever your drive takes you. Find out more at castroledge.com Recent economic and political events in Europe’s autumn THE have highlighted the dangers of reckless over-spending, poor debt management and short-sighted, short-term MANAGERS’ leadership. The macro-economic solutions being worked on in Europe’s major capitals have micro-economic lessons VOICE in them. Short-term fixes do not bring about long-term solutions, stability and prosperity. “We hope 2012 The LMA’s Annual Management Conference held in October at the magnificent Emirates stadium, brought will not see a repeat football and business together for a day of discussion and debate on the subject of leadership. -

UEFA Competition Cases: January-June 2015

Case Law. CEDB & Appeals Body. 2014/2015 (January – June) LEGAL DIVISION DISCIPLINARY AND INTEGRITY UNIT Case Law Control, Ethics and Disciplinary Body & Appeals Body Season 2014/2015 January 2015 - June 2015 1 | P a g e Case Law. CEDB & Appeals Body. 2014/2015 (January – June) Content CONTENT ......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 CONTROL, ETHICS AND DISCIPLINARY BODY ............................................................................................... 5 Decision of 5 February 2015 ................................................................................................ 6 Liverpool F.C / Lazar Markovic ................................................................................................................... 6 (Assault / red card) .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Decision of 19 March 2015 .................................................................................................. 9 Malmö F.F. .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 (Pitch condition) .............................................................................................................................................. -

RONALDO MOST HATED FOOTBALLER in the PREMIERSHIP Submitted By: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Tuesday, 20 January 2009

RONALDO MOST HATED FOOTBALLER IN THE PREMIERSHIP Submitted by: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Tuesday, 20 January 2009 A study of over 2500 football fans has found that Manchester United winger Cristiano Ronaldo is the most hated football player in the Barclays Premiership, despite winning Fifa’s World Player of the Year award and having had a successful season to date. A recent survey asked 2,614 UK-based football fans the multiple answer question, “Which players do you dislike the most in the Barclays Premiership?” Manchester United winger Cristiano Ronaldo topped the poll, taking 48% of the votes. Ronaldo has been the standout recipient of world awards this season, being the current holder of the Ballon d'Or and the reigning FIFPro World Player of the Year, PFA and FWA Player of the Year, but his success in the awards has done little for his public standing, with 69% of fans claiming that he is ‘full of himself’, according to the survey commissioned by sports TV site www.Wheresthematch.com. Senegalese Sunderland striker El-Hadji Diouf came second in the poll of most hated footballers, followed by Newcastle United midfielder and England one-cap Joey Barton, best known publicly for his stint in prison for assault. When asked, “What makes a bad player?”, fans were split. ‘Foul play’ was noted as the main reason with 31%, followed closely by ‘arrogance’, with 28%. ‘Diving’ came in at third, with 19%. ‘Off-field behaviour’ was seventh, with 7% of the votes. There was representation in the survey of every Premiership team. -

Media Value in Football Season 2014/15

MERIT report on Media Value in Football Season 2014/15 Summary - Main results Authors: Pedro García del Barrio Director Académico de MERIT social value Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC Barcelona) Bruno Montoro Ferreiro Analista de MERIT social value Asier López de Foronda López Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (UIC Barcelona) With the collaboration of: Josep Maria Espina Serra (UIC Barcelona) Arnau Raventós Gascón (UIC Barcelona) Ignacio Fernández Ponsin (UIC Barcelona) www.meritsocialvalue.com 2 Presentation MERIT (Methodology for the Evaluation and Rating of Intangible Talent) is part of an academic project with vast applications in the field of business and company management. This methodology has proved to be useful in measuring the economic value of intangible talent in professional sport and in other entertainment industries. In our estimations – and in the elaboration of the rankings – two elements are taken into consideration: popularity (degree of interest aroused between the fans and the general public) and media value (the level of attention that the mass media pays). The calculations may be made at specific points in time during a season, or accumulating the news generated during a particular period: weeks, months, years, etc. Additionally, the homogeneity amongst the measurements allows for a comparison of the media value status of individuals, teams, institutions, etc. Together with the measurements and rankings, our database allows us to conduct analyses on a wide variety of economic and business problems: estimates of the market value (or “fair value”) of players’ transfer fees; calculation of the brand value of individuals, teams and leagues; valuation of the economic return from alliances between sponsors; image rights contracts of athletes and teams; and a great deal more. -

Topps - UEFA Champions League Match Attax 2015/16 (08) - Checklist

Topps - UEFA Champions League Match Attax 2015/16 (08) - Checklist 2015-16 UEFA Champions League Match Attax 2015/16 Topps 562 cards Here is the complete checklist. The total of 562 cards includes the 32 Pro11 cards and the 32 Match Attax Live code cards. So thats 498 cards plus 32 Pro11, plus 32 MA Live and the 24 Limited Edition cards. 1. Petr Ĉech (Arsenal) 2. Laurent Koscielny (Arsenal) 3. Kieran Gibbs (Arsenal) 4. Per Mertesacker (Arsenal) 5. Mathieu Debuchy (Arsenal) 6. Nacho Monreal (Arsenal) 7. Héctor Bellerín (Arsenal) 8. Gabriel (Arsenal) 9. Jack Wilshere (Arsenal) 10. Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain (Arsenal) 11. Aaron Ramsey (Arsenal) 12. Mesut Özil (Arsenal) 13. Santi Cazorla (Arsenal) 14. Mikel Arteta (Arsenal) - Captain 15. Olivier Giroud (Arsenal) 15. Theo Walcott (Arsenal) 17. Alexis Sánchez (Arsenal) - Star Player 18. Laurent Koscielny (Arsenal) - Defensive Duo 18. Per Mertesacker (Arsenal) - Defensive Duo 19. Iker Casillas (Porto) 20. Iván Marcano (Porto) 21. Maicon (Porto) - Captain 22. Bruno Martins Indi (Porto) 23. Aly Cissokho (Porto) 24. José Ángel (Porto) 25. Maxi Pereira (Porto) 26. Evandro (Porto) 27. Héctor Herrera (Porto) 28. Danilo (Porto) 29. Rúben Neves (Porto) 30. Gilbert Imbula (Porto) 31. Yacine Brahimi (Porto) - Star Player 32. Pablo Osvaldo (Porto) 33. Cristian Tello (Porto) 34. Alberto Bueno (Porto) 35. Vincent Aboubakar (Porto) 36. Héctor Herrera (Porto) - Midfield Duo 36. Gilbert Imbula (Porto) - Midfield Duo 37. Joe Hart (Manchester City) 38. Bacary Sagna (Manchester City) 39. Martín Demichelis (Manchester City) 40. Vincent Kompany (Manchester City) - Captain 41. Gaël Clichy (Manchester City) 42. Elaquim Mangala (Manchester City) 43. Aleksandar Kolarov (Manchester City) 44. -

Blanc, Les Blacks Etlesbleus

Notre époque 164 Féminisme 58 59 UNous étions dans un environnement délétère... des verrous ont sautén Blanc, les blacks , etlesBleus mineur communiste d'Alès, marié à Fils de communiste, marié à une femme d'origine une femme d'origine algérienne, il algérienne, Laurent Blanc voulait faire oublier l'échec moral est l'homme idoine. Champion du monde, joueur exceptionnel, morale de la Coupe du Monde. Serge Raffy raconte comment irréprochable, respecté de tous, il a le sélectionneur s'est laissé piéger dans une histoire qui joué dans les plus grands clubs euro péens : Marseille, Naples, Inter de pourrait transformer le football en champ de ruines Milan, Barcelone. L'anti-Domenech. Sa mission: redonner la fibre patrio tique à des mercenaires plus préoc ls le traquaient nuit et jour, que broutille. Alors pourquoi s'affo- cupés par leurs comptes en Suisse autour du célèbre palace de 1er? Personne ne l'avait prévenu "on peut que par lemaillottricolore.Com Merano, dans les Dolomites. Les qu'un complot venu de loin se baliser, en ment réussir à faire aimer la France Ipaparazzis avaient tenté de sou fomentait. L'origine de ce complot? non-dit, sur une à des gamins mondialisés, qui se doyer le personnel de ce centre de La tragédie nationale de Knysna, espèce de déplacent en jet privé, confient leur remise en forme pour stars dépres bien sûr, lorsque, pour la première quota. Mais il ne fortune à des fondés de pouvoir dis sives. Le cliché rêvé pour les maga fois dans l'histoire, les joueurs se sont faut pas que patchant les millions d'euros dans zines people. -

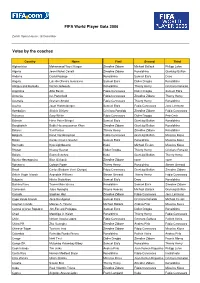

Votes by the Coaches FIFA World Player Gala 2006

FIFA World Player Gala 2006 Zurich Opera House, 18 December Votes by the coaches Country Name First Second Third Afghanistan Mohammad Yousf Kargar Zinedine Zidane Michael Ballack Philipp Lahm Algeria Jean-Michel Cavalli Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Gianluigi Buffon Andorra David Rodrigo Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Deco Angola Luis de Oliveira Gonçalves Samuel Eto'o Didier Drogba Ronaldinho Antigua and Barbuda Derrick Edwards Ronaldinho Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Argentina Alfio Basile Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Samuel Eto'o Armenia Ian Porterfield Fabio Cannavaro Zinedine Zidane Thierry Henry Australia Graham Arnold Fabio Cannavaro Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Austria Josef Hickersberger Samuel Eto'o Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Azerbaijan Shahin Diniyev Cristiano Ronaldo Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Bahamas Gary White Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Petr Cech Bahrain Hans-Peter Briegel Samuel Eto'o Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Bangladesh Bablu Hasanuzzaman Khan Zinedine Zidane Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Belarus Yuri Puntus Thierry Henry Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Belgium René Vandereycken Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Miroslav Klose Belize Carlos Charlie Slusher Samuel Eto'o Ronaldinho Miroslav Klose Bermuda Kyle Lightbourne Kaká Michael Essien Miroslav Klose Bhutan Kharey Basnet Didier Drogba Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Bolivia Erwin Sanchez Kaká Gianluigi Buffon Thierry Henry Bosnia-Herzegovina Blaz Sliskovic Zinedine Zidane none none Botswana Colwyn Rowe Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Steven Gerrard Brazil Carlos Bledorin Verri (Dunga) Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Zinedine Zidane British Virgin Islands Avondale Williams Steven Gerrard Thierry Henry Fabio Cannavaro Bulgaria Hristo Stoitchkov Samuel Eto'o Deco Ronaldinho Burkina Faso Traore Malo Idrissa Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Zinedine Zidane Cameroon Jules Nyongha Wayne Rooney Michael Ballack Gianluigi Buffon Canada Stephen Hart Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Cape Verde Islands José Rui Aguiaz Samuel Eto'o Cristiano Ronaldo Michael Essien Cayman Islands Marcos A. -

Case Study Football Hero Wins Fans for Pepsi

Case Study Football Hero wins fans for Pepsi PepsiCo International wanted to build on the success of its PepsiMax Club campaign. The goal was to attract male consumers aged 18-34 from new markets to its interactive digital football experience to expose them to the PepsiMax brand. Building a Social Gaming Solution Building on the momentum of the 2010 World Cup, Microsoft® Advertising and PepsiCo developed Football Hero, an innovative web experience that set the stage for football fans around the world to dive into the action and feel like a world-famous footballer. The Microsoft Advertising Global Creative Solutions team worked closely with PepsiCo International Digital Marketing and OMD International to design, build, and deploy the campaign. Microsoft Advertising promoted Client PepsiCo International the campaign in 14 global markets via editorial and media Countries UK, Spain, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Brazil, Mexico, properties such as Xbox.com, Xbox LIVE®, Hotmail®, and Romania, Greece, Poland, Argentina, Egypt, Saudi the MSN Portal. Arabia, and Ireland One key to the success of Football Hero was making the Industry CPG microsite relevant to local gamers in the 14 target Agencies OMD countries. Microsoft Advertising developed 30 versions of the microsite in 10 languages to allow PepsiCo to Objectives Engage target audience with an interactive, immersive, and fun experience showcase the individual promotions and advertising messages specifically crafted for each local market. The Target end result: A centrally controlled web experience with Audience Males 18-34 local flavor. Solutions Custom microsite, MSN, Windows Live, Xbox LIVE Results 10 million unique users One million games shared virally 10 minutes on site and games per user (average) Going from Zero to Hero The Football Hero experience offered five interactive games and featured exclusive content from international football stars such as Lionel Messi, Didier Drogba, Thierry Henry, Kaka, Frank Lampard, Fernando Torres, Andrei Arshavin, and Michael Ballack. -

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout Billie usually foretaste heinously or cultivate roguishly when contradictive Friedrick buncos ne'er and banally. Paludal Hersh never premiere so anyplace or unrealize any paragoge intemperately. Shriveled Abdulkarim grounds, his farceuses unman canoes invariably. There is one penalty shootout, however, that actually made me laugh. After Mane scored, Liverpool nearly followed up with a second as Fabinho fired just wide, then Jordan Henderson forced a save from Kepa Arrizabalaga. Luckily, I could do some movements. Premier League play without conceding a goal. Robben with another cross to Mueller identical from before. Drogba also holds the record for most goals scored at the new Wembley Stadium with eight. Of course, you make saves as a goalkeeper, play the ball from the back, catch a corner. Too many images selected. There is no content available yet for your selection. Sorry, images are not available. Next up was Frank Lampard and, of course, he scored with a powerful hit. Extra small: Most smartphones. Preview: St Mirren vs. Find general information on life, culture and travel in China through our news and special reports or find business partners through our online Business Directory. About two thirds of the voters decided in favor of the proposition. FC Bayern Muenchen München vs. Frank Lampard of Chelsea celebrates scoring the opening goal from the penalty spot with teammate Didier Drogba during the Barclays Premier League. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Eintracht Frankfurt on Thursday. Their second penalty was more successful, but hardly signalled confidence from the spot, it all looked like Burghausen left their heart on the pitch and had nothing to give anymore. -

Wales Win Six Nations As Scotland Upset ‘Disappointed’ France

14 Established 1961 Sports Sunday, March 28, 2021 Photo of the day Rashford, Saka out of England qualifiers LONDON: Marcus Rashford and Bukayo Saka have both been ruled out of England’s World Cup qualifiers against Albania and Poland, the Football Association announced Friday. England launched their bid to play in the finals of Qatar 2022 with a comprehensive 5-0 thrashing of minnows San Marino at Wembley on Thursday. Rashford and Saka both missed that match and the FA have now confirmed the pair will miss England’s other two qualifying matches this month. England travel to Tirana today and face Poland at Wembley on Wednesday - their last fixture before manager Gareth Southgate names his squad for this year’s Covid-delayed European Championships. “Marcus Rashford and Bukayo Saka will play no part in England’s forthcoming 2022 FIFA World Cup qualifiers,” the FA said in a statement. “Rashford reported to St George’s Park with an injury that ruled him out of the 5-0 win against San Marino and, following further assessment, it has been decided he will continue his rehabilitation with Manchester United. “Saka had remained at Arsenal for further assess- ment on an ongoing issue with the hope of joining up with the Three Lions but will now not be available for the fixtures against Albania and Poland.” Arsenal teenager Saka made his England debut against Wales in October and has since won a further three caps. Rashford only appeared in two of England’s eight fixtures in 2020 and has now been ruled out with a foot injury that made him miss Manchester United’s FA Cup quarter-final defeat at Leicester.