Universal Design in Architectural Education: Who Is Doing It? How Is It Being Done?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Curriculum in Art and Design

Planning Curriculum in Art and Design Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Planning Curriculum in Art and Design Melvin F. Pontious (retired) Fine Arts Consultant Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Tony Evers, PhD, State Superintendent Madison, Wisconsin This publication is available from: Content and Learning Team Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction 125 South Webster Street Madison, WI 53703 608/261-7494 cal.dpi.wi.gov/files/cal/pdf/art.design.guide.pdf © December 2013 Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction does not discriminate on the basis of sex, race, color, religion, creed, age, national origin, ancestry, pregnancy, marital status or parental status, sexual orientation, or disability. Foreword Art and design education are part of a comprehensive Pre-K-12 education for all students. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction continues its efforts to support the skill and knowledge development for our students across the state in all content areas. This guide is meant to support this work as well as foster additional reflection on the instructional framework that will most effectively support students’ learning in art and design through creative practices. This document represents a new direction for art education, identifying a more in-depth review of art and design education. The most substantial change involves the definition of art and design education as the study of visual thinking – including design, visual communications, visual culture, and fine/studio art. The guide provides local, statewide, and national examples in each of these areas to the reader. The overall framework offered suggests practice beyond traditional modes and instead promotes a more constructivist approach to learning. -

'Design for All' Versus 'One-Size-Fits-All': the Case Of

‘Design for All’ versus ‘One-Size-Fits-All’: the Case of Cultural Heritage 1 2 Daniela Fogli , Alberto Arenghi 1Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione Università degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy [email protected] 2Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile, Architettura, Territorio e Ambiente e di Matematica Università degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy [email protected] Abstract. This paper would like to discuss the design trade-offs that might emerge during the development of technological solutions for promoting and enhancing the fruition of cultural heritage. To this aim, the paper briefly describes the UniBSArt4All project, which employs advanced interactive technologies, such as artwork recognition and wireless sensors, to obtain engaging and accessible visitor experiences customized to different users’ profiles. By reflecting on the project development and its preliminary results, the paper finally proposes a meta-design approach to inclusive design in the CH domain. Keywords: Cultural heritage, augmented reality, beacon, end-user development, meta-design, inclusive design, design for all 1 Introduction In our everyday life, we often encounter trade-offs, namely situations where we need to renounce to something in order to gain something else. Problem solving usually represents such a situation, in which a solution must be designed by taking into account both the goals one would like to satisfy and the different constraints that impose choosing among those goals. Therefore, usually design “is the identification, discussion and resolution of trade-offs” [15]. Indeed, as underlined by Gerhard Fischer, a design problem does not have a correct solution or a right answer, but the solution or the answer depends on the values and interests of the involved stakeholders [6][7]. -

Ergonomics, Design Universal and Fashion

Work 41 (2012) 4733-4738 4733 DOI: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0761-4733 IOS Press Ergonomics, design universal and fashion Martins, S. B. Dr.ª and Martins, L. B.Dr.b a State University of Londrina, Department of Design, Rodovia Celso Garcia Cid Km. 380 Campus Universitário,86051-970, Londrina, PR, Brazil. [email protected] b Federal University of Pernambuco, Department of Design, Av. Prof. Moraes Rego, 1235, Cidade Universitária, 50670-901, Recife- PE, Brazil. [email protected] Abstract. People who lie beyond the "standard" model of users often come up against barriers when using fashion products, especially clothing, the design of which ought to give special attention to comfort, security and well-being. The principles of universal design seek to extend the design process for products manufactured in bulk so as to include people who, because of their personal characteristics or physical conditions, are at an extreme end of some dimension of performance, whether this is to do with sight, hearing, reach or manipulation. Ergonomics, a discipline anchored on scientific data, regards human beings as the central focus of its operations and, consequently, offers various forms of support to applying universal design in product development. In this context, this paper sets out a reflection on applying the seven principles of universal design to fashion products and clothing with a view to targeting such principles as recommendations that will guide the early stages of developing these products, and establish strategies for market expansion, thereby increasing the volume of production and reducing prices. Keywords: Ergonomics in fashion, universal design, people with disabilities 1. -

![[ENTER NAME of PROJECT] PROJECT CHARTER SMALL to MEDIUM PROJECTS [Enter Date] V1.0](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0065/enter-name-of-project-project-charter-small-to-medium-projects-enter-date-v1-0-230065.webp)

[ENTER NAME of PROJECT] PROJECT CHARTER SMALL to MEDIUM PROJECTS [Enter Date] V1.0

[ENTER NAME OF PROJECT] PROJECT CHARTER SMALL TO MEDIUM PROJECTS [Enter Date] V1.0 Campus Planning and Facilities Management – Design and Construction 1276 University of Oregon, Eugene OR 97403-1276 541-346-8292 | fax 541-346-6927 cpfm.uoregon.edu/design-construction An equal-opportunity, affirmative-action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act PROJECT NAME PROJECT NUMBER TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………….. 3 Purpose of the Project Charter ………………………………………… 3 2. BASIC PROJECT DELIVERY PROCESS ….……………………………… 4 3. PROJECT OVERVIEW/GOALS ……………………..……………………. 4 4. SCOPE ……………………………………………………………………. 5 4.1 Objectives ………………………………………………………… 5 4.2 Boundaries ……………………………………………………….. 5 5. ASSUMPTIONS AND RISKS ……………………………………………… 5 5.1 Assumptions ……………………………………………………... 5 5.2 Risks ……………………………………………………………... 5 5.3 Exclusions ………………………………………………………… 5 6. DURATION ……………………………………………………………….. 5 5.1Timeline …………………………………………………………... 5 7. BUDGET OPINION …………………………………………………... 6 6.1 Funding Source ………………………………………………..... 6 6.2 Estimate ………………………………………………………..... 6 8. CONTRACT METHODOLOY ………………………………………... …… 7 9. PROJECT ORGANIZATION ……………………………………………… 8 10. FUNDING SOURCES ……………………………………………………. 11 11. PROJECT CHARTER APPROVALS…………………………………….. 12 APPENDIX A: KEY ACRONYMS AND TERMS …………………………….. 13 APPENDIX B: REFERENCE MATERIALS …………………………………. 15 APPENDIX C: PROJECT CHARTER CHANGE TRACKING ........................ 16 Page 3 of 20 PROJECT NAME PROJECT NUMBER 1. INTRODUCTION -

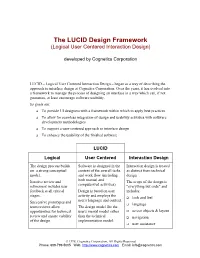

The LUCID Design Framework (Logical User Centered Interaction Design)

The LUCID Design Framework (Logical User Centered Interaction Design) developed by Cognetics Corporation LUCID – Logical User Centered Interaction Design – began as a way of describing the approach to interface design at Cognetics Corporation. Over the years, it has evolved into a framework to manage the process of designing an interface in a way which can, if not guarantee, at least encourage software usability. Its goals are: q To provide UI designers with a framework within which to apply best practices q To allow for seamless integration of design and usability activities with software development methodologies q To support a user-centered approach to interface design q To enhance the usability of the finished software LUCID Logical User Centered Interaction Design The design process builds Software is designed in the Interaction design is treated on a strong conceptual context of the overall tasks as distinct from technical model. and work flow (including design. both manual and Iterative review and The scope of the design is computerized activities). refinement includes user "everything but code" and feedback at all critical Design is based on user includes: stages. activity and employs the q look and feel user's language and context. Successive prototypes and q language team reviews allow The design model fits the opportunities for technical user's mental model rather q screen objects & layout review and ensure viability than the technical q navigation of the design implementation model. q user assistance © 1998, Cognetics Corporation, All Rights Reserved Phone: 609-799-5005 Web: http://www.cognetics.com Email: [email protected] An Introduction to the LUCID Framework Page 2 Over the past 30 years, several techniques for managing software development projects have been developed and documented. -

Design for All: Not Excluded by Design

A Friendly Rest Room: Developing Toilets of the Future for Disabled and Elderly People 7 J.F.M. Molenbroek et al. (Eds.) IOS Press, 2011 © 2011 The authors. All rights reserved. doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-752-9-7 Design for All: Not Excluded by Design Johan F.M. MOLENBROEKa,1, Theo J.J. GROOTHUIZENb, R. DE BRUINc a Faculty of Industrial Design – Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands b Design Consultant – Groothuizen Beheer bv, Rotterdam, The Netherlands c Erin Ergonomics and Industrial Design, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Abstract. Inclusive Design or Design for All refers to the design philosophy of including as many users groups as possible in the target population of a to-be- designed product and to be aware of the ones that are excluded. This paper explains about the history, current status and possibilities of Inclusive Design as strategy. Within the FRR-project this strategy was leading when design decisions had to be taken. The outcome is a truly Friendly Rest Room, fulfilling the needs of disabled and elderly in a non-stigmatizing manner, and thus favoured by us all. Keywords: Inclusive Design, Design for All, Universal Design 1. Introduction 1.1. The Need to Design for All In Europe and the Western world in general, the quality of life for its inhabitants has dramatically improved over the last couple of decades. The numbers of people that reach the age of 65 have been fast growing. For instance in the Netherlands 6% of the population in 1900 was aged 65+ to more than 12% in 2000 and perhaps 25% in 2050. -

Inclusive Design for Mobile Devices with WCAG and Attentional Resources in Mind

Linköping University | Department of Computer and Information Science Master’s thesis, 30 credits | Cognitive science Spring term 2020 | ISRN: LIU-IDA/KOGVET-A--20/010--SE Inclusive Design for Mobile Devices with WCAG and Attentional Resources in Mind An investigation of the sufficiency of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines when designing inclusively and the effects of limited attentional resources. Josefin Carlbring Tutor: Erik Marsja (IBL) Examinator: Arne Jönsson (IDA) Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – for a period of 25 years starting from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. The online availability of the document implies permanent permission for anyone to read, to download, or to print out single copies for his/hers own use and to use it unchanged for non-commercial research and educational purpose. Subsequent transfers of copyright cannot revoke this permission. All other uses of the document are conditional upon the consent of the copyright owner. The publisher has taken technical and administrative measures to assure authenticity, security and accessibility. According to intellectual property law the author has the right to be mentioned when his/her work is accessed as described above and to be protected against infringement. For additional information about the Linköping University Electronic Press and its procedures for publication and for assurance of document integrity, please refer to its www home page: http://www.ep.liu.se/. © Josefin Carlbring ii iii Abstract When designing for the general population it is important to design inclusively in order to invite to participation in today’s digital society. -

9.2 MB Fort Mcnair Design Narrative

Design Narrative 100% Design Submission FY21 - McNair Group 01 Quarters 10 - 15 USACE Project reference: JBMHH Army Family Housing Project number: 60615576 June 09, 2021 Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family Housing Solicitation Number – W912DR21BXXXX Prepared for: USACE AECOM Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family Housing Solicitation Number – W912DR21BXXXX Quality information Prepared Checked Verified by Approved by by by Blank Blank Blank Blank Krista Joshua Ryan Krista Kehrer Levy Horner/Troy Kehrer Project Metz Manager Revision History Revision Revision Details Authorized Name Position date 0 Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Distribution List # Hard PDF Association / Company Name Copies Required Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank blank Prepared for: USACE AECOM Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family Housing Solicitation Number – W912DR21BXXXX Prepared for: USACE W912DR21BXXXX -W912DR19F0647 Vivian Wong 2 Hopkins Plaza Baltimore, MD 21201 Prepared by: Krista Kehrer Project Manager T: 703-682-4973 M: 703-867-7948 E: [email protected] AECOM 3101 Wilson Boulevard Arlington, VA 22201 aecom.com Copyright © 2019 by AECOM All rights reserved. No part of this copyrighted work may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of AECOM. Prepared for: USACE AECOM Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family -

What Is Universal Design…Inclusive Design…Design-For-All?

What is universal design…inclusive design…design-for-all? …a framework for the design of places, things, information, communication and policy that focuses on the user, on the widest range of people operating in the widest range of situations without special or separate design. Or, more simply: Human-Centered design (of everything) with everyone in mind Universal Design Principles: Equitable Use: The design does not disadvantage or stigmatize any group of users. Flexibility in Use: The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities. Simple, Intuitive Use: Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level. Perceptible Information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities. Tolerance for Error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions. Low Physical Effort: The design can be used efficiently and comfortably, and with a minimum of fatigue. Size and Space for Approach & Use: Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use, regardless of the user’s body size, posture, or mobility. [Developed by a group of US designers and design educators from five organizations in 1997. Principles are copyrighted to the Center for Universal Design, School of Design, State University of North Carolina at Raleigh. The Principles are in use internationally.] Relationship between Legally Mandated Accessibility & Inclusive Design Legally mandated requirements for accessible design, within a civil or human rights context, provide a vital basis for autonomy and equal opportunity for people with disabilities. -

Urban Environment Development Based on Universal Design Principles

E3S Web of Conferences 31, 09010 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20183109010 ICENIS 2017 Urban Environment Development based on Universal Design Principles Bangun IR Harsritanto1,* 1Architecture Department of Engineering Faculty, Diponegoro University, Semarang - Indonesia Abstract. Universal Design is a design which facilitated full range of human diversity. By applying Universal design principles, urban environment can be more functional and more user-friendly for everyone. This study examined five urban streets of South Korea as a country experienced on developing various urban street designs based on universal design. This study aimed to examine and compare the South Korea cases using seven principles of universal design. The research methods of this study are literature study, case study, and site observation. The results of this study are: South Korea cases are good practices, urgency of implementing the direction into local regulations; and change of urban development paradigm. 1 Introduction 2. Site observation was used to inspect South Korea urban streets with evaluation sheet which Urban streetscape which designed and developed in constructed before, and measured by interval scales detail with a special theme or purpose of urban of five points. development. However, not all people can access the 3. Case study was used to explain several phenomena specialized street easily because of their different ability happening on the site observation and later on can (as the elderly, children and people with special needs). be generalized into the bigger scope of research Universal design (also called inclusive design or area. accessible design) refers to facility designs that accommodate the widest range of potential users, including people with mobility and visual disabilities 3 Discussions and other special needs [11]. -

Engineering an Undergraduate Innovation Eco-System

First in Europe - First in Ireland - First in Innovation Engineering an Undergraduate Innovation Eco-System Pictorial Compendium of International & National Innovation Awards Vincent Forde pictured with Sons Sacha, Blaise and Jude Enterprise Ireland Student Entrepreneur Awards Overall Winner and Student Entrepreneur of the Year 2016 Vincent Forde, Gasgon Medical, Cork Institute of Technology CIT Multidisciplinary Teams Win All Five Major Awards at National Finals (1) Enterprise Ireland Overall Winner and Student Entrepreneur of the Year 2016 (2) Cruickshank Intellectual Property Attorneys National Award 2016 (3) Grant Thornton National Award 2016 (4)Intel ICT National Award 2016 (5)Enterprise Ireland Academic Innovation National Award 2016 National Prize-Winners in Engineering Innovation, Design & Entrepreneurship Innovative Product Development Laboratories Recent National student successes include: Three Enterprise Ireland / Invest Northern Ireland Young Entrepreneur of the Year First Place National Awards ( 2016, 2013, 2007 ) Three Enterprise Ireland / Invest Northern Ireland Academic Innovation National Awards ( 2016, 2012, 2009 ) One Accenture Leaders of Tomorrow First Place National Award Accenture HQ Grand Canal Square Dublin ( 2016 ) Five Enterprise Ireland Cruickshank Most Technologically Innovative Project First Place National Awards(2016, 2013, 2009, 2008, 2007) Nine MEETA Asset Management and Maintenance National Awards ( 2016(x2), 2015(x2), 2014, 2013(x2), 2011, 2006 ) One James Dyson Design National Award Ireland ( 2016 ) -

Guide to the Elaine Ostroff Universal Design Papers

Guide to the Elaine Ostroff Universal Design Papers NMAH.AC.1356 Alison Oswald 2016 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Personal/Biographical Materials, 1967 - 2008.......................................... 5 Series 2: Subject Files, 1965 - 2008....................................................................... 7 Series 3: Universal Design Education Program Files,