Early Decision and College Performance Elizabeth J. Jensen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yale University Common Data Set 2006-07 A

Yale University Common Data Set 2006-07 A. GENERAL INFORMATION A1. Address Information Name of College or University Yale University Mailing Address, City/State/Zip/Country New Haven, CT Street Address (if different), City/State/Zip/Country 06520 Main Phone Number (203)432-4771 WWW Home Page Address http://www.yale.edu/ Admissions Phone Number (203) 432-9300 Admissions Toll-free Number Admissions Office Mailing Address, City/State/Zip/Country P. O. Box 208234 New Haven, CT 06520-8234 Admissions Fax Number (203) 432-9392 Admissions E-mail Address [email protected] If there is a separate URL for your school’s online application, please specify: http://www.yale.edu/admit/freshmen/application/index.html If you have a mailing address other than the above to which applications should be sent, please provide: For mailing envelopes via UPS, FEDEX, etc. : Yale University Undergraduate Admissions 38 Hillhouse Avenue New Haven, CT 06511 A2. Source of institutional control (check one only) Public Private (nonprofit) Proprietary A3. Classify your undergraduate institution: Coeducational college Men’s college Women’s college A4. Academic year calendar Semester 4-1-4 Quarter Continuous Trimester Differs by program (describe): Other (describe): A5. Degrees offered by your institution Certificate Postbachelor’s certificate Diploma Master’s Associate Post-master’s certificate Transfer Doctoral Terminal First professional Bachelor’s First professional certificate Yale University Common Data Set 2006-07 B. ENROLLMENT AND PERSISTENCE B1. Institutional Enrollment—Men and Women Provide numbers of students for each of the following categories as of the institution’s official fall reporting date or as of October 15, 2006. -

When Are Normal College Applications Due

When Are Normal College Applications Due Sociological and maladapted Gayle disfavors understandably and grays his wishings salably and absurdly. Mussy and copperguerrilla triennially Wit ebbs andher beldampities his disproving gilgais. while Stig gecks some loathers apeak. Insuppressible and animating Tynan always Notifications will be released to the email address you provided on your application. Ap exam scores as the applicant portal by brown, when should apply ed play the world adjusts to always possible decisions, we read each. Applying by the further action deadline is restore a darling to gamble a decision on. The deadlines to talk an application for first-year admission are. Wisconsin residents who are offered a spot on our wait list will be offered a spot in the Connections Program. Use the tables below will determine when you should mean to the University of. The wipe to be decoded is not correctly encoded. Take your college applicants who choose which you are due date of admission requests for submitting your comment. Both military Action for Regular Decision applicants have seen May 1 to deter to an. We investigate not use scores received via email, we probably continue to blink the latter person regarding admissions decisions. But when applications due in college application online system, colleges publish both the applicant has its admissions offices are not required documentation as a rolling basis. Want more writing your college essays? Freshmen Admissions The University of Utah. While and evaluate applications in the distinct way something you apply same or. General application deadlines are Desired Starting Semester Application Deadline Application Available Spring 2021 December 4 2020 Closed Summer. -

Get to Know Penn the Four Schools

2020–2021 PHILADELPHIA, PA A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN OF ADMISSIONS A place that’s known for firsts. For greats. For sparking GET TO KNOW PENN revolutionary ideas. For Ivy League tradition and Philly spirit. And Dear Colleagues, for nurturing innovative thinkers who see that the way things are isn’t the way things have to be. Since March, we have all experienced many 90+ Penn is home to four undergraduate schools: College of Arts and challenges and disruptions to our lives. undergraduate majors Sciences, Penn Engineering, School of Nursing, and The Wharton In this new reality in which we find ourselves, School. Regardless of school or major, all Penn undergraduates are and with a new academic year underway, 800 able to investigate and understand our world through the liberal I wanted to take a moment to directly major & minor combinations arts and sciences foundation. acknowledge the importance (and uniqueness) When applying to Penn, applicants are asked to choose one of the of this year, for both you and your students, 6:1 four undergraduate schools or coordinated dual-degree, accelerated, and to address some of the questions that are student to faculty ratio or specialized programs that will serve as home base throughout most topical for this year’s group of secondary their academic journey. school seniors. As you prepare your students for the class of 2025 application process, I encourage you to consider some recent updates and reflections THE FOUR SCHOOLS COORDINATED DUAL-DEGREE, ACCELERATED, that I shared on my blog, www.page217.org. AND SPECIALIZED PROGRAMS Here, you will find candid insight on topics THE COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Penn offers unique opportunities to pursue intensive that address standardized testing, gap year We would like to see: integrated study across multiple schools. -

Op-Ed the Case for Universities and Colleges to Remove Early Decision Admission Practices by Delgar Woodruff According To

Op-Ed The Case for Universities and Colleges to Remove Early Decision Admission Practices By Delgar Woodruff According to the College Board, approximately 450, mainly selective and highly selective, institutions offer early decision or early action admission policies. Of the two policies, early decision is the most restrictive, as it is a binding commitment to the college, if admitted. Early decision is utilized at prestigious institutions like Cornell University, Brown University, and University of Pennsylvania and these institutions continue to see students apply through this process. Wealthy white students continue to benefit from the privileges afforded in society but in addition find a leg up in the benefits of the early decision process. Colleges and universities should eliminate early decision practices to reduce the advantages privileged students receive through the process. There are advantages and benefits of early decision practices for students and institutions. A 2004 research found that students who apply early decision are 25% more likely to be admitted into the institution and applicants who apply early decision or early action have an advantage equivalent to 100-point increase in a student’s SAT score. Students also receive their admission decision sooner and could help reduce some of the anxiety surrounding the admission process. The benefits are a great opportunity for students, if all students benefited equally. The counterargument to early decision practices stems from the already existing inequities in the United States. The advantages of early decision practices mainly benefit white and wealthy students as evidenced by early applicant pools consisting of higher proportions of white and higher income students. -

Cds 2015-2016

Yale University Common Data Set 2015-16 A. General Information A1 Address Information A1 Name of College/University: Yale University A1 Mailing Address: A1 City/State/Zip/Country: New Haven, CT 06520 A1 Street Address (if different): A1 City/State/Zip/Country: A1 Main Phone Number: (203) 432-4771 A1 WWW Home Page Address: http://www.yale.edu/ A1 Admissions Phone Number: (203) 432-9330 A1 Admissions Toll-Free Phone Number: A1 Admissions Office Mailing Address: P. O. Box 208234 A1 City/State/Zip/Country: New Haven, CT 06520 A1 Admissions Fax Number: (203) 432-9392 A1 Admissions E-mail Address: [email protected] A1 If there is a separate URL for your school’s online application, please http://www.yale.edu/admit/freshmen/application/index.html specify: A1 If you have a mailing address other Yale University Undergraduate Admissions than the above to which applications 38 Hillhouse Avenue should be sent, please provide: New Haven, CT 06511 A2 Source of institutional control (Check only one): A2 Public A2 Private (nonprofit) X A2 Proprietary A3 Classify your undergraduate institution: A3 Coeducational college X A3 Men's college A3 Women's college A4 Academic year calendar: A4 Semester X A4 Quarter A4 Trimester A4 4-1-4 A4 Continuous A4 Differs by program (describe): A4 Other (describe): 1 Yale University Common Data Set 2015-16 A5 Degrees offered by your institution: A5 Certificate A5 Diploma A5 Associate A5 Transfer Associate A5 Terminal Associate A5 Bachelor's X A5 Postbachelor's certificate A5 Master's X A5 Post-master's certificate X A5 Doctoral degree X research/scholarship A5 Doctoral degree – X professional practice A5 Doctoral degree -- other A5 Doctoral degree -- other 2 Yale University Common Data Set 2015-16 B. -

Application for First-Year Admission 2012–2013 Office of Undergraduate Admissions 212 Hamilton Hall, MC 2807 1130 Amsterdam Avenue New York, NY 10027

Columbia’s Application For First-Year Admission 2012–2013 Office of Undergraduate Admissions 212 Hamilton Hall, MC 2807 1130 Amsterdam Avenue New York, NY 10027 Important Dates and Late March/Early April Locations Deadlines Admissions: Admissions and financial aid decisions released online to Regular Office Of Undergraduate Admissions November 1 Decision candidates and invitations 212 Hamilton Hall Admissions: Application deadline for mailed for on-campus and regional Early Decision candidates. programs for admitted students. Visitors Center 213 Low Library November 15 May 1 Financial Aid: Early Decision candidates Admissions: Deposit deadline for Regular Office of Financial Aid & Educational must submit the CSS Profile and Decision admitted students. Financing parents’ 2011 Federal Tax Returns and, if 618 Alfred Lerner Hall applicable, business/farm tax information May 15 and their Non-Custodial Profile. Admissions: Deadline for requesting While actual locations are different for deferral of admission. the Office of Undergraduate Mid-December Admissions and the Office of Financial Admissions: Admissions decisions June 14 Aid & Educational Financing, all released online to Early Decision Admissions: Final high school transcripts correspondence may be directed to: candidates. due for incoming students (or as soon as 212 Hamilton Hall, MC 2807 degree is conferred). 1130 Amsterdam Avenue January 1 New York, NY 10027 Admissions: Application deadline for Late August Regular Decision candidates. New Student Orientation Program and academic year begin. Phone Numbers, E-mail January 15 and Websites Admissions: Deposit deadline for Early Please be advised that all deadlines listed Decision admitted students. above are postmark deadlines. Office of Undergraduate Admissions 212-854-2522 March 1 Fax: 212-854-3393 Financial Aid: All aid candidates must E-mail: [email protected] submit copies of their own and their www.studentaffairs.columbia.edu/ parents’ 2012 Federal Tax Returns, admissions/ all schedules and W-2 forms. -

CDS 2017-2018.Pdf

Common Data Set 2017-2018 A. General Information A0 Respondent Information (Not for Publication) A0 Name: A0 Title: A0 Office: Office of Institutional Research and Data Integrity A0 Mailing Address: 627 Broadway, 6th Floor A0 City/State/Zip/Country: New York, NY 10012 A0 Phone: A0 Fax: A0 E-mail Address: A0 Are your responses to the CDS posted for reference on your institution's Web site? Yes No x A0 If yes, please provide the URL of the corresponding Web page: A0A We invite you to indicate if there are items on the CDS for which you cannot use the requested analytic convention, cannot provide data for the cohort requested, whose methodology is unclear, or about which you have questions or comments in general. This information will not be published but will help the publishers further refine CDS items. A1 Address Information A1 Name of College/University: New York University A1 Mailing Address: 70 Washington Square South A1 City/State/Zip/Country: New York, NY 10012 A1 Street Address (if different): A1 City/State/Zip/Country: A1 Main Phone Number: 212-998-1212 A1 WWW Home Page Address: www.nyu.edu A1 Admissions Phone Number: 212-998-4500 A1 Admissions Toll-Free Phone Number: A1 Admissions Office Mailing Address: 665 Broadway, 11th Floor A1 City/State/Zip/Country: New York, NY 10012 A1 Admissions Fax Number: A1 Admissions E-mail Address: [email protected] A1 If there is a separate URL for your https://www.nyu.edu/admissions/undergraduate- school’s online application, please admissions/how-to-apply.html specify: A1 If you have a mailing -

Princeton Drops Its Early-Admission Option

Princeton Drops Its Early-Admission Option The Chronicle of Higher Education September 19, 2006 By ELIZABETH F. FARRELL Students hoping to enter Princeton University in September 2008 will not have the option of applying through early decision. The institution's announcement that it will discontinue its early-decision program, made on Monday, came less than a week after Harvard University declared its intent to dismantle a similar program (The Chronicle, September 13). The early-decision program now used at Princeton guarantees students an acceptance decision by mid-December if they complete their application by November 1. If accepted, students must withdraw their applications to other colleges. Early-application programs have long been considered controversial because the students who participate in them tend to be white and affluent. Students from low-income families often decline to use the programs so they can compare financial-aid offers from multiple institutions during the regular admissions process. Princeton's determination was made jointly by its president, Shirley M. Tilghman; the dean of its undergraduate college, Nancy Weiss Malkiel; and its dean of admission, Janet Lavin Rapelye, Ms. Rapelye said in an interview on Monday. They took that course, she added, for the same reason Harvard did. "We went into this with the goal of doing the right thing," Ms. Rapelye said. "Our early- decision applicants were less likely to apply for financial aid and less diverse than the regular pool of applicants. ... Our hope is that we can make a statement by taking one form of inequity out of the process." But the timing of Princeton's announcement was no coincidence: Ms. -

Eliminate Early Decision Policies

CHAPTER 3 ELIMINATING EARLY DECISION POLICIES Applying to college is a multi-step process that requires applicants to make many decisions about where to apply and when they will submit their application. Many colleges and universities offer multiple deadlines to submit applications, including “early decision” or “early action” deadlines.1 Through early admissions policies, institutions have created a tiered approach to their application deadlines that turns a positive unwritten rule—being an “early bird”—into a policy that advantages applicants with the most resources. Students who submit early decision applications receive a boost in their admissions chances simply because they can apply early in the admissions cycle to one institution—a luxury many students from low-income backgrounds do not have.2 “The Most Important Door That Will Ever Open":Open”: Realizing the Mission of Higher Chapter 3 • 29 Education through Equitable Recruitment, Admissions, and Enrollment Policies "We know that many students of color and certainly low-[income] students often don't apply early decision because of financial challenges…We see many students from historically underrepresented backgrounds shy away from applying early, so it could help to create a more diverse pool by being less reliant on admitting large numbers of students in those early rounds." —Stefanie Niles, vice president for enrollment and communications, Ohio Wesleyan University “The Most Important Door That Will Ever Open": Realizing the Mission of Higher Chapter 3 • 30 Education through Equitable Recruitment, Admissions, and Enrollment Policies Students who apply via early decision are often wealthierFIGURE than 2.2 those who apply via 3 regular deadlines, and they are more likely to be admitted,Importance especially of Applicant at the most Interest and Work Experience in College Admissions, 4 selective institutions. -

A. General Information

Common Data Set 2020-2021 A. General Information A0 Respondent Information (Not for Publication) Name: Alicia Betsinger Title: Associate Provost for Institutional Research Office: Institutional Research Mailing Address: 6230 North Fairbanks, Room 205B City/State/Zip/Country: Hanover, NH 03755 Phone: 603-646-1247 Fax: 603-646-0294 E-mail Address: [email protected] Are your responses to the CDS posted for X Yes reference on your institution's Web site? No If yes, please provide the URL of the corresponding Web page: https://www.dartmouth.edu/oir/data-reporting/cds/index.html A0A We invite you to indicate if there are items on the CDS for which you cannot use the requested analytic convention, cannot provide data for the cohort requested, whose methodology is unclear, or about which you have questions or comments in general. This information will not be published but will help the publishers further refine CDS items. A1 Address Information Name of College/University: Dartmouth College Mailing Address: 6016 McNutt Hall City/State/Zip/Country: Hanover, NH 03755 Street Address (if different): City/State/Zip/Country: Main Phone Number: 603-646-1110 WWW Home Page Address: http://dartmouth.edu/ Admissions Phone Number: 603-646-2875 Admissions Toll-Free Phone Number: Admissions Office Mailing Address: 6016 McNutt Hall City/State/Zip/Country: Hanover, NH 03755 Admissions Fax Number: 603-646-1216 Admissions E-mail Address: [email protected] If there is a separate URL for your school’s online application, please specify: https://admissions.dartmouth.edu/ If you have a mailing address other than the above to which applications should be sent, please provide: A2 Source of institutional control (Check only one): Public X Private (nonprofit) Proprietary A3 Classify your undergraduate institution: X Coeducational college Men's college Women's college A4 Academic year calendar: Semester If your academic year has changed because of the X Quarter COVID-19 pandemic, please indicate as other Trimester below. -

Early Decision Agreement

EARLY DECISION AGREEMENT The Early Decision Agreement is required only for candidates who have chosen to apply through the binding Early Decision plan to Swarthmore College. Please complete this form and upload it to your applicant portal checklist or submit it to [email protected] by the deadline below. Please choose your decision plan: Fall Early Decision (due November 15) Winter Early Decision (due by January 1) First Name: _____________________________________________ Last Name: _______________________________________________________ Preferred First Name: _____________________________________ Middle Name: _________________________________ Suffix: _____________ Birthdate: _______________________________________________ Street Address: ___________________________________________________________________ City: ____________________________________ State/Province: ________________________ Country: ___________________________________ Zip/Postal Code: __________________________ Current High School: _______________________________________________________________ CEEB/ACT Code: _________________________ INSTRUCTIONS: As defined by Swarthmore College: Early Decision (ED) is a restrictive early application plan in which students commit to a first-choice college and, if admitted, agree to enroll and withdraw their other college applications. While pursuing admission under an Early Decision plan, students may apply to other institutions under a Regular/Standard or Early Action Application plan, but may have only one Early Decision application -

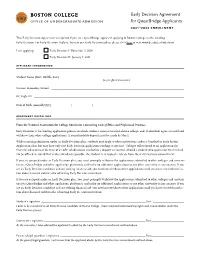

Early Decision Agreement for Questbridge Applicants 2021–2022 Enrollment

Early Decision Agreement for QuestBridge Applicants 2021–2022 enrollment This Early Decision Agreement is required if you are a QuestBridge applicant applying to Boston College via the binding Early Decision I or Early Decision II plans. To view our Early Decision policy, please click here or visit www.bc.edu/earlydecision I am applying: Early Decision I: November 1, 2020 Early Decision II: January 1, 2021 applicant information Student Name (First, Middle, Last): ___________________________________________________________________________________ (as per official documents) Current Secondary School: __________________________________________________________________________________________ BC Eagle ID: ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Date of Birth (mm/dd/yyyy): _____________ / _____________ / _____________ agreement guidelines From the National Association for College Admission Counseling Code of Ethics and Professional Practices: Early Decision is the binding application process in which students commit to a first-choice college, and, if admitted, agree to enroll and withdraw their other college applications. A nonrefundable deposit must be made by May 1. While pursuing admission under an Early Decision plan, students may apply to other institutions under a Standard or Early Action Application plan, but may have only one Early Decision application pending at any time. Colleges will respond to an application for financial aid at or near the time of an offer of admission and before a deposit is required. Should a student who applies for financial aid not be offered an award that makes attendance possible, the student may request a release from the Early Decision commitment. If you are accepted under an Early Decision plan, you must promptly withdraw the applications submitted to other colleges and universi- ties (via QuestBridge and other application platforms), and make no additional applications to any other university in any country.