Actsofcivility: Implicit Arguments for the Role of Ci- Vility and the Paradox of Confrontation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christie and Mrs. Mccain

Oliver Harper: [0:11] It's my great pleasure to have been asked yesterday to introduce Cindy McCain and Governor Christie. The Harpers have had the special privilege of being friends with the McCains for many years, social friends, political friends, and great admirers of the family. [0:33] Cindy is a remarkable person. She's known for her incredible service to the community, to the country, and to the world. She has a passion for doing things right and making the world better. [0:48] Cindy, after her education at USC in special ed, became a teacher at Agua Fria High School in special ed and had a successful career there. She also progressed to become the leader of the family company, Hensley & Company, and continues to lead them to great heights. [1:13] Cindy's interest in the world and special issues has become very apparent over the years. She serves on the board of the HALO Trust. She serves on the board of Operation Smile and of CARE. [1:31] Her special leadership as part of the McCain Institute and her special interest and where her heart is now is in conquering the terrible scourge of human trafficking and bringing those victims of human trafficking to a full, free life as God intended them to have. [1:57] I want to tell you just a quick personal experience with the McCains. Sharon and I will socialize with them often. We'll say, "What are you going to be doing next week, Sharon or Ollie?" [2:10] Then we'll ask the McCains what they're doing. -

Impact Report the Sedona Forum Award for Courage and Leadership

impact report 2017 The Sedona Forum Award for Courage and Leadership Next Generation Leaders Combatting Human Trafficking Human Rights And Democracy Global Rule of Law and Governance Events Leadership Training 5-Year Highlights LEADERSHIP TRAINING MCCain Institute at arizona state university 1 THE MISSION Guided by values that have animated the career of Senator John McCain and the McCain family for generations, ASU’s McCain Institute is a non- partisan do-tank dedicated to advancing message from character-driven global leadership based on security, economic opportunity, freedom and human dignity – in the United States our Executive Director and around the world. Dear Friends, It my great pleasure to present to you • Our Global Rule of Law and as U.S. Special Representative for the McCain Institute’s annual Impact Governance program has also Ukraine Negotiations. I continue to Report. The following pages outline experienced compelling growth, lead the Institute while volunteering Board of Trustees our most significant accomplishments already attracting considerable my efforts to establish peace and in 2017. funding in grants in its first full year restore Ukraine’s sovereignty and of operations. territorial integrity. Although Ukraine Kelly Ayotte Robert Day David H. Petraeus The year marked the Institute’s continues to suffer, I am pleased that David Berry Phil Handy Lynn Forester de Rothschild fifth anniversary. Since its launch The McCain Institute is proud to be our efforts have raised awareness of in 2012, the Institute has achieved part of Arizona State University, which the ongoing conflict, clarified U.S. Don Brandt Sharon Harper Rick Shangraw growth and impact well beyond our under the leadership of Dr. -

Reassessing U. S. International Broadcasting

REASSESSING U. S. INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING S. ENDERS WIMBUSH ELIZABETH M. PORTALE MARCH 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 3 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 7 II. THE WORLD TODAY AND THE CHANGED MEDIA ENVIRONMENT ............................. 16 III. MISSION ........................................................................................................................................ 21 IV. THE GREAT DIVIDE: PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND SURROGATE BROADCASTING ..... 25 V. AMERICAN VALUES .................................................................................................................... 29 VI. TELLING AMERICA’S STORY ................................................................................................... 33 VII. AUDIENCES ................................................................................................................................. 38 VIII. NETWORK INDEPENDENCE, OBJECTIVE JOURNALISM AND FIREWALLS ............ 42 IX. DOES BROADCASTING CONNECT TO U.S. FOREIGN POLICY STRATEGIES? ............ 46 X. CAN IT BE FIXED? POSSIBLE NEW MODELS ....................................................................... 52 XI. WHY NOT START OVER: A NEW PARADIGM ..................................................................... 55 APPENDIX: INTERVIEWEES ............................................................................................................ -

Afghanistan Stay Or Go

Kurt Volker: [0:01] ...illuminate some complex policy issues, giving different points of view equal and fair time and making sure that we try to take the partisanship out of the debate so we get to the real issues that underlie our options as a country. [0:14] Tonight's debate will focus on Afghanistan. America's been involved in Afghanistan for nearly 12 years. There's been remarkable progress in education, health care, women's rights, children, governance, the economy. And yet, there has come, at a cost of hundreds of billions of dollars, thousands of lives. The question remains, is it really sustainable? [0:37] We're now committed to a transition in Afghanistan, as President Obama said, ending America's war in Afghanistan by the end of 2014. But is Afghanistan ready? And what will happen when America leaves? On the other hand, would it really be any better if we stayed? [0:54] We have four distinguished panelists tonight representing four distinct perspectives on Afghanistan and US policy. We hope that their debate helps eliminate the challenges that we still face as a country. [1:05] Before introducing our moderator, allow me to introduce the man whose life and whose family has inspired the creation of this institute, the man who's dedicated his family and his career to national service, Senator John McCain. [applause] Senator John McClain: [1:22] Thank you very much, Kurt. I'd like to thank Jenna Lee, who's going to be our moderator here and our panelists, all of whom I have had the opportunity of knowing and interacting with over a number of years. -

Reinvigorating U.S. Efforts to Promote Human Rights in China

REINVIGORATING U.S. EFFORTS TO PROMOTE HUMAN RIGHTS IN CHINA MAY 2017 ABOUT THE STRAUSS CENTER The Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law integrates expertise from across the University of Texas at Austin, as well as from the private and public sectors, in pursuit of practical solutions to emerging international challenges. The Robert Strauss Center’s Understanding China program features both a speaker series on campus at UT (focused on improving understanding of China’s evolving role in the international system) and a planned research-and-conference series examining China’s human rights record. ABOUT THE MCCAIN INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL LEADERSHIP AT ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Guided by values that have animated the career of Senator John McCain and the McCain family for generations, the McCain Institute is a non-partisan do-tank dedicated to advancing character-driven global leadership based on security, economic opportunity, freedom and human dignity – in the United States and around the world. The Institute seeks to promote humanitarian action, human rights and democracy, and national security, and to embrace technology in producing better designs for educated decisions in national and international policy. The McCain Institute is committed to: sustaining America’s global leadership; upholding freedom, democracy and human rights as universal human values; supporting humanitarian goals; maintaining a strong, smart national defense; and serving causes greater than one’s self-interest. The Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law at the University of Texas at Austin and the McCain Institute for International Leadership at Arizona State University convened a workshop in November 2016 in Washington DC, where policy-makers (past and present), scholars, practitioners, and dissidents met to brainstorm and refine policy-relevant, concrete recommendations for more effectively advancing human rights in China. -

Georgian Orthodox Church; the Country’S Hopeful but Fragile Transition to Democracy; And, of Course, Its Past and Present Relationship to Russia

GEORGIA’S INFORMATION ENVIRONMENT THROUGH THE LENS OF RUSSIA’S INFLUENCE PREPARED BY THE NATO STRATEGIC COMMMUNICATIONS CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE 1 Georgia’s Information Environment through the Lens of Russia’s Influence Project Director: Elīna Lange-Ionatamišvili Project Manager: James McMillan Content Editors: Elīna Lange-Ionatamišvili, James McMillan Language Editors: Tomass Pildagovičs, James McMillan Authors: Nino Bolkvadze, Ketevan Chachava, Gogita Ghvedashvili, Elīna Lange-Ionat- amišvili, James McMillan, Nana Kalandarishvili, Anna Keshelashvili, Natia Kuprashvili, Tornike Sharashenidze, Tinatin Tsomaia Design layout: Tornike Lordkipanidze We would like to thank our anonymous peer reviewers from King’s College London for their generous contribution. ISBN: 978-9934-564-36-9 This publication does not represent the opinions or policies of NATO or NATO StratCom COE. © All rights reserved by the NATO StratCom COE. Reports may not be copied, reproduced, distributed or publicly displayed without reference to the NATO StratCom COE. The views expressed here do not represent the views of NATO. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................7 CHAPTER 1: GEORGIA’S STRATEGIC INTERESTS ............................................. 11 By Tornike Sharashenidze CHAPTER 2: RUSSIA’S STRATEGIC INTERESTS IN GEORGIA .......................... 23 By Nana Kalandarishvili -

1) Birds of a Feather... You Know the Saying... They CLAIM to Fight Child Trafficking, but Do They REALLY? in This Thread

WhiteHatWannabee @HatWannabee 8 Nov 19 • 52 tweets • HatWannabee/status/1192779317597614081 1) Birds of a feather... you know the saying... They CLAIM to fight child trafficking, but do they REALLY? In this thread, we are going to take a look at some who are HIGHLY suspect! http://www.slaveryfreeworld.org/congressman-erik- paulsen-holds-an-anti-trafficking-roundtable-in-dc/ 2) We will work backwards through this list as some of these organizations were outed long ago. The #McCain Institute had a terrible track record! At the very least, "McCain Institute Caught Stealing Millions In Child Trafficking Donations" McCain Institute Steals Millions In Child Trafficking Donations Th M C i I tit t l i it i t t fi ht h t ffi ki b t d it illi The McCain Institute claims it exists to fight human trafficking, but despite millions in donations none was spent on human trafficking. https://newspunch.com/mccain-institute-child-trafficking/ 3) It is widely believed that the McCains were involved in trafficking in AZ. Here is Cindy McCain sporting her pedo swirl, as well as the tell tale medical boot that suggests she has an ankle monitor. McStain abandoned his first wife to marry into this major crime family. 4) John Kasich was famously filmed admitting that McStain was "put to death" while Meghan McCain's comment "you can't kill him again" was also captured, verifying that the penalty for his Crimes Against Humanity was indeed, severe. 5) Moving on to the next known criminal enterprise, in Q drop 1830, we were advised: Clinton Foundation Linked to National Human Trafficking Hotline COUNTLESS organizations used this number, most notably, the Polaris Project which is a member of the Clinton Global Initiative 6) We even discovered an organization that distributed the phone number to hotels and events surrounding the Super Bowl; America's event that has the highest incidents of human trafficking. -

Timeline of Alleged Ukrainian- Democrat Meddling in 2016 Presidential Election

12/14/19, 1027 PM Page 1 of 1 ! LOG IN SUBSCRIBE The Democratic National Headquarters in Washington on Jan. 30, 2018. (Samira Bouaou/The Epoch Times) MORE US NEWS Timeline of Alleged Ukrainian- Democrat Meddling in 2016 Presidential Election BY SHARYL ATTKISSON November 25, 2019 Updated: December 11, 2019 Experience the best way to read The Epoch Times online. Download our app here. As we rapidly approach Campaign 2020, Democrats! 37 CommentsComments and Republicans! have fired! up a! new debate about which foreign entities tried to interfere in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Turn your phone into a beacon of freedom and independent news. Download The Epoch Times app. Both sides agree that Russian interests made attempts to meddle in the 2016 campaign. Special counsel Robert Mueller wasn’t able to connect any Americans to the alleged scheme, but filed a case against 13 Russians. He charged that they were instructed to write social media posts opposing Clinton and “to support Bernie Sanders and then- candidate Donald Trump.” Although it hasn’t been widely reported, Mueller also testified there were instances of Russian social media support for Hillary Clinton as well. But there’s widespread disagreement on the role Ukraine may have had in U.S. election interference in 2016. This past week, Democrats stepped up efforts to dismiss such allegations as “debunked” and a “conspiracy theory.” Republicans doubled down, stating that the alleged Ukrainian efforts may not have been a “top-down” operation—as they believe Russia’s was—but could have been significant all the same and deserve serious investigation. -

DEFENSE ACQUISITION REFORM: WHERE DO WE GO from HERE? a Compendium of Views by Leading Experts

United States Senate PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Carl Levin, Chairman John McCain, Ranking Minority Member DEFENSE ACQUISITION REFORM: WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? A Compendium of Views by Leading Experts STAFF REPORT PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE October 2, 2014 SENATOR CARL LEVIN Chairman SENATOR JOHN McCAIN Ranking Minority Member PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS ELISE J. BEAN Staff Director and Chief Counsel HENRY J. KERNER Staff Director and Chief Counsel to the Minority BRADLEY M. PATOUT Senior Policy Advisor to the Minority LAUREN M. DAVIS Professional Staff Member to the Minority MARY D. ROBERTSON Chief Clerk 10/2/14 Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations 199 Russell Senate Office Building – Washington, D.C. 20510 Majority: 202/224-9505 – Minority: 202/224-3721 Web Address: http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/subcommittees/investigations DEFENSE ACQUISITION REFORM: WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? A Compendium of Views by Leading Experts TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 1 II. BIOGRAPHIES AND ESSAYS PROVIDED BY CONTRIBUTORS ............. 5 1. Brigadier General Frank J. Anderson, USAF (Ret.) ........................... 5 2. The Honorable Norman R. Augustine ...................................... 11 3. Mr. David J. Berteau ................................................... 17 4. Mr. Irv Blickstein...................................................... 23 5. General James Cartwright, -

THE STAINS of JOHN Mccain

REMEMBER JOHN MCCAIN AS A WARMONGER AND A CUNNING OPPORTUNIST AND LEAVE THE HERO WORSHIP TO HIS LACKEYS THE STAINS OF JOHN McCAIN BY STEPHEN LEMONS EDITED BY TOM FINKEL • ILLUSTRATION BY RICHARD BORGE By Stephen Lemons edited by Tom Finkel Cover Illustration by Richard Borge Front Page Confidential: News, commentary, and historical per- spectives on all matters related to free speech. The website is pub- lished by Michael Lacey and Jim Larkin and edited by Tom Finkel. © 2018 Front Page Confidential. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: McCain the MiNO: Maverick in Name Only He cultivated the image of a political iconoclast, but McCain’s track record as a flip-flopper with the ethical conscience of a weathervane earned him the sobriquet “Jukebox John.” 7 Chapter 2: Low Friends in High Places New to Arizona, McCain embraced Darrow “Duke” Tully and Charles Keating, Jr., two frauds whose respective scandals marred the up-and- coming politician’s record. 21 Chapter 3: Sweetheart of Saudi Arabia A serial human-rights abuser and suspected backer of international ter- rorism, Saudi Arabia furnished $1 million to McCain’s namesake nonprof- it, the McCain Institute for International Leadership. A grateful senator promotes the Middle Eastern nation’s interests in Congress. 34 Chapter 4: The Making of a Militarist McCain should be remembered for his warmongering and jingoism, particularly in regard to the cataclysmic U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, and for milking his status as a former POW throughout his political career, shamelessly using it to further his ambitions. 43 Chapter 5: Family Ties Following his return from Vietnam, McCain left his handicapped first wife for a comely Arizona beer heiress – a calculating first step on his rise to prominence and power. -

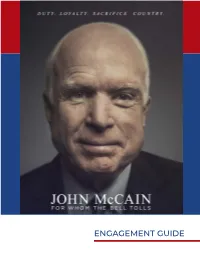

Engagement Guide Table of Contents

ENGAGEMENT GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION > 3 USING THIS GUIDE > 4 LEARNING OBJECTIVES > 5 FILM SUMMARY > 6 KEY PEOPLE > 7 BEFORE SCREENING > 9 INTERACTIVE DISCUSSION > 11 ACTIVITIES > 16 JOHN MCCAIN | 2 INTRODUCTION Legendary six-term US senator and war hero John McCain agreed to participate in this documentary near the end of his life, providing unprecedented access to his daily activities in Washington, DC, and at home in Arizona. This sweeping account combines the senator’s own voice—culled from original interviews, commentary, and speeches—with archival news footage and previously unseen home movies and photographs. The film also features interviews with family, friends, colleagues, and other leading political figures. Senator McCain’s continuing crusade for the causes he believed in, even during his battle with brain cancer, underscores his fighting spirit and resilience. What emerges is a portrait of a maverick with an unerring sense of duty who never forgot the most important American ideals. JOHN MCCAIN | 3 USING THIS GUIDE This discussion guide is designed as a tool for high school classroom teachers and facilitators to incorporate excerpts of the 2018 HBO film John McCain: For Whom the Bell Tolls and over 28 hours of additional interview footage in the Interview Archive on the Kunhardt Film Foundation website. These materials are an informative and inspiring complement to teaching US history, government, and civics. They illustrate the significance of bipartisanship, moral leadership, and ethical decision-making. Through a rich visual retelling of McCain’s causes and alliances, a portrait of a man dedicated to ideas, rather than party, emerges. -

CHINA: Is Engagement Still Working

p.1 CHINA: Is Engagement Still Working Paris Dennard: Good evening. My name is Paris Dennard. I'm the Events Director here at the McCain Institute. We're delighted to have all of you here. I want you to do me a favor. If you have an iPhone, anything that's a device that rings, that buzzes, we want it to buzz tonight, so put it on vibrate for me. But I want you to participate throughout the course of tonight's debate. If you're on Twitter or Facebook or Instagram, please, first, follow us, @McCainInstitute. I see some of you all from our last debate. I asked you if you followed us and you said, "No." I hope tonight we can change your mind and you follow us, @McCainInstitute on Twitter, on Facebook and on Instagram, and our YouTube page as well. Throughout the course of tonight's event, you can look inside of here and you can see the Twitter hashtag for tonight's debate. That page, it says "MIDebateChina." Use that hashtag. Our moderator @TomNagorski and the rest of our panelists have their Twitter handles there as well. I hope that you will be engaged tonight. Let people know where you are, let them know that you're excited, and let them know what you're listening to this evening. Last point. There will be a portion for question and answer, so please, if you have the microphone given to you, please stand up, let the audience know your name and your affiliation. Make it easier on everyone that's here.