Popularization of Mongol Language and Culture in the Late Koryŏ Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Romancing race and gender : intermarriage and the making of a 'modern subjectivity' in colonial Korea, 1910-1945 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9qf7j1gq Author Kim, Su Yun Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Romancing Race and Gender: Intermarriage and the Making of a ‘Modern Subjectivity’ in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Su Yun Kim Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Yoneyama, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Jin-kyung Lee Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Yingjin Zhang 2009 Copyright Su Yun Kim, 2009 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Su Yun Kim is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………...……… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………... iv List of Figures ……………………………………………….……………………...……. v List of Tables …………………………………….……………….………………...…... vi Preface …………………………………………….…………………………..……….. vii Acknowledgements …………………………….……………………………..………. viii Vita ………………………………………..……………………………………….……. xi Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………. xii INTRODUCTION: Coupling Colonizer and Colonized……………….………….…….. 1 CHAPTER 1: Promotion of -

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Women's Life During the Chosŏn Dynasty

International Journal of Korean History(Vol.6, Dec.2004) 113 Women’s Life during the Chosŏn Dynasty Han Hee-sook* 1 Introduction The Chosŏn society was one in which the yangban (aristocracy) wielded tremendous power. The role of women in this society was influenced greatly by the yangban class’ attempts to establish a patriarchal family order and a Confucian-based society. For example, women were forced, in accordance with neo-Confucian ideology, to remain chaste before marriage and barred from remarrying once their husbands had passed away. As far as the marriage system was concerned, the Chosŏn era saw a move away from the old tradition of the man moving into his in-laws house following the wedding (男歸女家婚 namgwiyŏgahon), with the woman now expected to move in with her husband’s family following the marriage (親迎制度 ch΄inyŏng jedo). Moreover, wives were rigidly divided into two categories: legitimate wife (ch΄ŏ) and concubines (ch΄ŏp). This period also saw a change in the legal standing of women with regards to inheritance, as the system was altered from the practice of equal, from a gender standpoint, rights to inheritance, to one in which the eldest son became the sole inheritor. These neo-Confucianist inspired changes contributed to the strengthening of the patriarchal system during the Chosŏn era. As a result of these changes, Chosŏn women’s rights and activities became increasingly restricted. * Professor, Dept. of Korean History, Sookmyung Women’s University 114 Women’s Life during the Chosŏn Dynasty During the Chosŏn dynasty women fell into one of the following classifications: female members of the royal family such as the queen and the king’s concubines, members of the yangban class the wives of the landed gentry, commoners, the majority of which were engaged in agriculture, women in special professions such as palace women, entertainers, shamans and physicians, and women from the lowborn class (ch’ŏnin), which usually referred to the yangban’s female slaves. -

Nomadic Incursion MMW 13, Lecture 3

MMW 13, Lecture 3 Nomadic Incursion HOW and Why? The largest Empire before the British Empire What we talked about in last lecture 1) No pure originals 2) History is interrelated 3) Before Westernization (16th century) was southernization 4) Global integration happened because of human interaction: commerce, religion and war. Known by many names “Ruthless” “Bloodthirsty” “madman” “brilliant politician” “destroyer of civilizations” “The great conqueror” “Genghis Khan” Ruling through the saddle Helped the Eurasian Integration Euroasia in Fragments Afro-Eurasia Afro-Eurasian complex as interrelational societies Cultures circulated and accumulated in complex ways, but always interconnected. Contact Zones 1. Eurasia: (Hemispheric integration) a) Mediterranean-Mesopotamia b) Subcontinent 2) Euro-Africa a) Africa-Mesopotamia 3) By the late 15th century Transatlantic (Globalization) Africa-Americas 12th century Song and Jin dynasties Abbasids: fragmented: Fatimads in Egypt are overtaken by the Ayyubid dynasty (Saladin) Africa: North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa Europe: in the periphery; Roman catholic is highly bureaucratic and society feudal How did these zones become connected? Nomadic incursions Xiongunu Huns (Romans) White Huns (Gupta state in India) Avars Slavs Bulgars Alans Uighur Turks ------------------------------------------------------- In Antiquity, nomads were known for: 1. War 2. Migration Who are the Nomads? Tribal clan-based people--at times formed into confederate forces-- organized based on pastoral or agricultural economies. 1) Migrate so to adapt to the ecological and changing climate conditions. 2) Highly competitive on a tribal basis. 3) Religion: Shamanistic & spirit-possession Two Types of Nomadic peoples 1. Pastoral: lifestyle revolves around living off the meat, milk and hides of animals that are domesticated as they travel through arid lands. -

Proposal for a Korean Script Root Zone LGR 1 General Information

(internal doc. #: klgp220_101f_proposal_korean_lgr-25jan18-en_v103.doc) Proposal for a Korean Script Root Zone LGR LGR Version 1.0 Date: 2018-01-25 Document version: 1.03 Authors: Korean Script Generation Panel 1 General Information/ Overview/ Abstract The purpose of this document is to give an overview of the proposed Korean Script LGR in the XML format and the rationale behind the design decisions taken. It includes a discussion of relevant features of the script, the communities or languages using it, the process and methodology used and information on the contributors. The formal specification of the LGR can be found in the accompanying XML document below: • proposal-korean-lgr-25jan18-en.xml Labels for testing can be found in the accompanying text document below: • korean-test-labels-25jan18-en.txt In Section 3, we will see the background on Korean script (Hangul + Hanja) and principal language using it, i.e., Korean language. The overall development process and methodology will be reviewed in Section 4. The repertoire and variant groups in K-LGR will be discussed in Sections 5 and 6, respectively. In Section 7, Whole Label Evaluation Rules (WLE) will be described and then contributors for K-LGR are shown in Section 8. Several appendices are included with separate files. proposal-korean-lgr-25jan18-en 1 / 73 1/17 2 Script for which the LGR is proposed ISO 15924 Code: Kore ISO 15924 Key Number: 287 (= 286 + 500) ISO 15924 English Name: Korean (alias for Hangul + Han) Native name of the script: 한글 + 한자 Maximal Starting Repertoire (MSR) version: MSR-2 [241] Note. -

2021 Workshop

2021 WORKSHOP: How did I never notice that your username is Santa Claus and mine is reindeer? Produced by Olivia Murton, Kevin Wang, Wonyoung Jang, Jordan Brownstein, Adam Fine, Will Holub-Moorman, Athena Kern, JinAh Kim, Zachary Knecht, Caroline Mao, Christopher Sims, and Will Grossman Packet 13 Tossups 1. The final manuscript of this collection, known as its “Chigi” (“KEE-jee”) form, is discussed in Ernest Wilkins’s book titled The Making of [this collection]. While at his country home in France, the speaker of this collection laments their “sixteenth year of sighs.” A woman in this collection appears along with Love, Chastity, Death, and Fame in the collection Triumphs. Sections titled (*) “In Life” and “In Death” divide this collection, which ends with a poem addressed to the Virgin Mary. This collection was popularized through translations by the Earl of Surrey and Thomas Wyatt. This collection begins, “You who hear the sound in scattered rhymes,” and is about a woman the author met on Good Friday. For 10 points, name this collection of 366 poems by Petrarch dedicated to Laura (“LAO-rah”). ANSWER: Il Canzoniere [or Songbook] <FW, European Literature> 2. A piece in this genre opens with the low strings playing the recurring theme F-sharp, D, C-sharp, D, B, [pause] low F-sharp, which then modulates up by a third every two measures. Sir Donald Tovey referred to a section of a non-Beethoven piece in this genre as “The Great Bassoon Joke” because it includes dueling bassoons playing a “Fox Song”; that piece concludes with a C major maestoso finale section. -

Lesson Title the Yuan Empire, the Silk Road and the Mongols Class

Lesson Title The Yuan Empire, the Silk Road and the Mongols Class and Grade level(s) History, Grades 6-8 Goals and Objectives The student will be able to: Identify the boundaries of the Mongol Empire Understand that Mongol rule was a time of cosmopolitan cultural exchange in China and across Asia Understand the values of the Mongol leaders that underlined this cultural exchange Understand how this might have differed from those of the Chinese dynasties that came before them, particularly the Song dynasty Understand the concept of Eurasia and the Silk Road Appreciate that a desire for global trade seen in the operation of the Silk Road foreshadowed the exploration and colonization of the Americas Connect the exchange of ideas and goods along the Silk Road to our current exchanges through the internet, and compare the spread of ideas (cultural diffusion) throughout the Mongolian Empire to the spread of American ideas throughout the world Read, understand and contextualize two primary sources. Time required/class periods needed 5 class periods, 44 minutes each. Primary source bibliography 1. Marco Polo’s description in translation at: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/china/polo_hangzhou.pdf 2. Objects traded on the Silk Road http://www.advantour.com/silkroad/goods.htm 3. The Beijing Qing Ming Scroll, viewable at: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/song/pop/c_scroll.htm interactive roll-over version: http://www.npm.gov.tw/exh96/orientation/flash_4/index.html Other resources used http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols/ Two lesson plans about Marco Polo’s travels: http://edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plan/marco-polo- takes-trip http://edsitement.neh.gov/curriculum-unit/road-marco-polo (This one has an interactive map that allows students to take Polo’s route by answering questions about his travels) Required materials/supplies Outline maps of Eurasia Colored pencils and paper Vocabulary Mongol, Yuan dynasty, Silk Road, Confucianism, caravan Procedure First Class Period 1. -

Mongolian Interest in Architecture and Construction in China (7Th C

REVIEW OF INTERNATIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL EDUCATION ISSN: 2146-0353 ● © RIGEO ● 11(4), WINTER, 2021 www.rigeo.org Research Article Mongolian Interest in Architecture and Construction in China (7th C. AH/ 13th C. AD) Prof. Dr. Suaad Hadi Hassan Al-Taai Department of History, College of Education ibn Rushd for Humanities, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq [email protected] Abstract The Mongols were interested in architecture and construction, whether in Mongolia or China, especially after they mixed with civilized peoples. They merged with them and were affected by their civilization and their arts, and they borrowed a lot from them, especially in the field of construction and architecture. After establishing his rule in China, Kublai (658-693 A.H., 1260-1294 A.D.) was keen on building a new capital for him, which he called Dadu, to replace his previous capital, Khanbaliq. After consulting with the wise men of his palace and astrologers, Kublai was interested in building luxurious palaces for himself and his family, and he used a large number of engineers and craftsmen to build them to be a model for contemporary cities and compete with them in architecture and luxury. Kublai gave several priorities to build his capital by providing it with large funds to provide all service institutions its residents need. He split rivers, built canals, reclaimed and cultivated lands, built roads, Keywords Kublai, Engineers, Walls, Rivers, The Capital, Princesses. To cite this article: Al-Taai, Prof.Dr, S, H, H.; (2021) Mongolian Interest in Architecture and Construction in China (7th C. AH/ 13th C. -

The Mongol and Ming Empire

Zhu Yuanzhang a peasant leader, created a rebel army that defeated the Mongols and pushed them back beyond the Great Wall It could be cruel if you were not a Mongol. Mongols had more privileges than Chinese people. The Mongols held more government jobs. And If you were Chinese you had to pay a tribute to the Mongols at the end of each month They restored the civil service system They were able to delegate responsibility to lower levels of government to reduce corruption They improved new ways for farming and restored the canal to improve trading What advantage would riding on horseback have during warfare? Section 2 Unit 12 The Mongols were nomadic people who grazed their horses and sheep in Central Asia In the early 1200’s, a brilliant Mongol chieftain united tribes. This chieftain took the name Genghis Khan meaning “universal ruler” Mongol forces conquered a vast empire that stretched from the Pacific Ocean to Eastern Europe Genghis Khan demanded absolute loyalty His army had the most skilled horsemen in the world He could order the massacre of an entire city The Mongols and the Chinese would often attack each other by launching missiles against each other from metal tubes filled with gunpowder Although Genghis Khan did not live to complete his conquest of China his heirs continued to expand the empire. The Mongols dominated much of Asia The Mongols allowed people they conquered to live peaceful lives as long as they paid tribute to the Mongols In the 1200’s and 1300’s the sons and grandsons of Genghis Khan established peace and order. -

From Kashgar to Xanadu in the Travels of Marco Polo Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

From Kashgar to Xanadu in the Travels of Marco Polo Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. From Kashgar to Xanadu in the Travels of Marco Polo. 2020. hal- 02563026 HAL Id: hal-02563026 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02563026 Preprint submitted on 5 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. From Kashgar to Xanadu in the Travels of Marco Polo Amelia Carolina Sparavigna Politecnico di Torino Uploaded 21 April 2020 on Zenodo DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3759380 Abstract: In two previous papers (Philica, 2017, Articles 1097 and 1100), we investigated the travels of Marco Polo, using Google Earth and Wikimapia. We reconstructed the Polo’s travel from Beijing to Xanadu and from Sheberghan to Kashgar. Here we continue the analysis of this travel from today Kashgar to Xanadu. Keywords: Satellite Images, Google Earth, Wikimapia, Marco Polo, Taklamakan, Southwest Xinjiang, Lop Desert, Xanadu, Marco Polo, China. The Travels of Marco Polo is a 13th-century book writen by Rustchello da Pisa, reportng the stories told by Marco to Rustchello while they were in prison together in Genoa. This book is describing the several travels through Asia of Polo and the period that he spent at the court of Kublai Khan [1]. -

Chapter 4: China in the Middle Ages

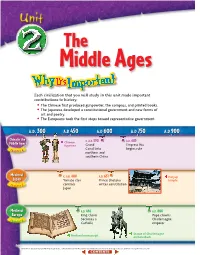

The Middle Ages Each civilization that you will study in this unit made important contributions to history. • The Chinese first produced gunpowder, the compass, and printed books. • The Japanese developed a constitutional government and new forms of art and poetry. • The Europeans took the first steps toward representative government. A..D.. 300300 A..D 450 A..D 600 A..D 750 A..DD 900 China in the c. A.D. 590 A.D.683 Middle Ages Chinese Middle Ages figurines Grand Empress Wu Canal links begins rule Ch 4 apter northern and southern China Medieval c. A.D. 400 A.D.631 Horyuji JapanJapan Yamato clan Prince Shotoku temple Chapter 5 controls writes constitution Japan Medieval A.D. 496 A.D. 800 Europe King Clovis Pope crowns becomes a Charlemagne Ch 6 apter Catholic emperor Statue of Charlemagne Medieval manuscript on horseback 244 (tl)The British Museum/Topham-HIP/The Image Works, (c)Angelo Hornak/CORBIS, (bl)Ronald Sheridan/Ancient Art & Architecture Collection, (br)Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 0 60E 120E 180E tecture Collection, (bl)Ron tecture Chapter Chapter 6 Chapter 60N 6 4 5 0 1,000 mi. 0 1,000 km Mercator projection EUROPE Caspian Sea ASIA Black Sea e H T g N i an g Hu JAPAN r i Eu s Ind p R Persian u h . s CHINA r R WE a t Gulf . e PACIFIC s ng R ha Jiang . C OCEAN S le i South N Arabian Bay of China Red Sea Bengal Sea Sea EQUATOR 0 Chapter 4 ATLANTIC Chapter 5 OCEAN INDIAN Chapter 6 OCEAN Dahlquist/SuperStock, (br)akg-images (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tr)Werner Forman/Art Resource, NY, (c)Ancient Art & Archi NY, Forman/Art Resource, (tr)Werner (tc)National Museum of Taipei, (tl)Aldona Sabalis/Photo Researchers, A..D 1050 A..D 1200 A..D 1350 A..D 1500 c. -

Chinggis Khan on Film: Globalization, Nationalism, and Historical Revisionism

Volume 16 | Issue 22 | Number 1 | Article ID 5214 | Nov 15, 2018 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Chinggis Khan on Film: Globalization, Nationalism, and Historical Revisionism Robert Y. Eng Few personalities in world history have had a (which had been replaced by the Cyrillic more compelling personal story or a greater script), the rehabilitation of Chinggis Khan, and impact on the world than Temüjin, who rose the revival of Tibetan Buddhism. Mongols from destitute circumstances to be crowned as celebrated the rediscovery of Chinggis Khan as Chinggis Khan in 1206 and became the founder a national symbol through religious of the world’s greatest contiguous land empire. celebrations, national festivals, academic Today, eight and a half centuries after his birth, conferences, poetic renditions, art exhibitions, Chinggis Khan remains an object of personal and rock songs.3 His name and image were also and collective fascination, and his image and commodified. The international airport at life story are appropriated for the purposes of Ulaanbaatar is named after Chinggis, as are constructing national identity and commercial one of the capital’s fanciest hotels and one of profit. its most popular beers. Chinggis’ image appears on every denomination of the Vilified as a murderous tyrant outside his Mongolian currency. homeland, yet celebrated by the Mongols as a great hero and object of cultic worship for This revival of a national cult, one that had centuries,1 Chinggis Khan’s reputation been banned during the socialist era, is a underwent an eclipse even in Mongolia when it response to endemic corruption, growing fell under Soviet domination in the early economic inequalities, and a host of other twentieth century.