A Primer on ASEAN Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Higher Education Database Whed Iau Unesco

WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO Página 1 de 438 WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO Education Worldwide // Published by UNESCO "UNION NACIONAL DE EDUCACION SUPERIOR CONTINUA ORGANIZADA" "NATIONAL UNION OF CONTINUOUS ORGANIZED HIGHER EDUCATION" IAU International Alliance of Universities // International Handbook of Universities © UNESCO UNION NACIONAL DE EDUCACION SUPERIOR CONTINUA ORGANIZADA 2017 www.unesco.vg No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted without written permission. While every care has been taken in compiling the information contained in this publication, neither the publishers nor the editor can accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions therein. Edited by the UNESCO Information Centre on Higher Education, International Alliance of Universities Division [email protected] Director: Prof. Daniel Odin (Ph.D.) Manager, Reference Publications: Jeremié Anotoine 90 Main Street, P.O. Box 3099 Road Town, Tortola // British Virgin Islands Published 2017 by UNESCO CENTRE and Companies and representatives throughout the world. Contains the names of all Universities and University level institutions, as provided to IAU (International Alliance of Universities Division [email protected] ) by National authorities and competent bodies from 196 countries around the world. The list contains over 18.000 University level institutions from 196 countries and territories. Página 2 de 438 WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO World Higher Education Database Division [email protected] -

Masterlist of Private Schools Sy 2011-2012

Legend: P - Preschool E - Elementary S - Secondary MASTERLIST OF PRIVATE SCHOOLS SY 2011-2012 MANILA A D D R E S S LEVEL SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL HEAD POSITION TELEPHONE NO. No. / Street Barangay Municipality / City PES 1 4th Watch Maranatha Christian Academy 1700 Ibarra St., cor. Makiling St., Sampaloc 492 Manila Dr. Leticia S. Ferriol Directress 732-40-98 PES 2 Adamson University 900 San Marcelino St., Ermita 660 Manila Dr. Luvimi L. Casihan, Ph.D Principal 524-20-11 loc. 108 ES 3 Aguinaldo International School 1113-1117 San Marcelino St., cor. Gonzales St., Ermita Manila Dr. Jose Paulo A. Campus Administrator 521-27-10 loc 5414 PE 4 Aim Christian Learning Center 507 F.T. Dalupan St., Sampaloc Manila Mr. Frederick M. Dechavez Administrator 736-73-29 P 5 Angels Are We Learning Center 499 Altura St., Sta. Mesa Manila Ms. Eva Aquino Dizon Directress 715-87-38 / 780-34-08 P 6 Angels Home Learning Center 2790 Juan Luna St., Gagalangin, Tondo Manila Ms. Judith M. Gonzales Administrator 255-29-30 / 256-23-10 PE 7 Angels of Hope Academy, Inc. (Angels of Hope School of Knowledge) 2339 E. Rodriguez cor. Nava Sts, Balut, Tondo Manila Mr. Jose Pablo Principal PES 8 Arellano University (Juan Sumulong campus) 2600 Legarda St., Sampaloc 410 Manila Mrs. Victoria D. Triviño Principal 734-73-71 loc. 216 PE 9 Asuncion Learning Center 1018 Asuncion St., Tondo 1 Manila Mr. Herminio C. Sy Administrator 247-28-59 PE 10 Bethel Lutheran School 2308 Almeda St., Tondo 224 Manila Ms. Thelma I. Quilala Principal 254-14-86 / 255-92-62 P 11 Blaze Montessori 2310 Crisolita Street, San Andres Manila Ms. -

Enhancing Curriculum in Philippine Schools in Response to Global Community Challenges

Edith Cowan University Research Online EDU-COM International Conference Conferences, Symposia and Campus Events 1-1-2008 Enhancing Curriculum in Philippine Schools in Response to Global Community Challenges Luisito C. Hagos Our Lady of Fatima University Erlinda G. Dejarme Our Lady of Fatima University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ceducom Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons EDU-COM 2008 International Conference. Sustainability in Higher Education: Directions for Change, Edith Cowan University, Perth Western Australia, 19-21 November 2008. This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ceducom/21 Hagos, L.C. and Dejarme, E.G., Our Lady of Fatima University, Philippines Enhancing Curriculum in Philippine Schools in Response to Global Community Challenges Luisito C. Hagos1 and Erlinda G. Dejarme2 1Our Lady of Fatima University Valenzuela, Philippines 2Our Lady of Fatima University Valenzuela, Philippines ABSTRACT The world is changing so fast that in order for schools and universities to cope with new innovations, they should keep at pace with the tempo of societal changes and technological progress. The schools of today should participate in the educational and social revolution. Thus, the curriculum in Philippine schools today has to be geared to the rapid societal changes and the new responsibilities for the new breed of Filipinos. The three most important sectors of society that give direct input to the improvement of the curriculum are the academe (institutions), the government, and the industries (both public and private companies). Some government institutions, such as the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) and the Department of Education (DepEd), are directly involved in upgrading the curricular programs of learning institutions. -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta. -

Directory of Higher Education Institutions As of October 23, 2009

Directory of Higher Education Institutions as of October 23, 2009 04001 Abada College Private Non-Sectarian President : Atty. Miguel D. Ansaldo, Jr. Region : IVB - MIMAROPA Address : Marfrancisco, Pinamalayan, Oriental Mindoro 5208 Telephone : (043) 443-13-56 (043)284-41-50 Fax : (043)443-13-56 E-mail : Year Established : April 26, 1950 Website : 06128 ABE International Coll of Business and Economics-Bacolod Private Non-Sectarian School Director : Joretta M. Abraham Region : VI - Western Visayas Address : Luzuriaga Street, Bacolod City, Negros Occidental 6100 Telephone : (034)-432-2484 to 85 Fax : E-mail : [email protected] Year Established : 2001 Website : www.amaes.edu.ph 01122 ABE International College of Business and Accountancy Private Non-Sectarian School Director : Mr. Juanito Mendiola Region : I - Ilocos Region Address : 3rd flr. E&R Bldg. Malolos Crossing, City of Malolos (Capital), Bulacan, Cebu City, Bulacan 2428 Telephone : (032) 234-2421 Fax : (044)662-1018 E-mail : [email protected]/abe_urdaneta_city@hot mail.com Year Established : 2001 Website : http://amaes.educ.ph. 13309 ABE International College of Business and Accountancy-Las Piñas Private Non-Sectarian President : Mr. Amable C. Aguiluz IX Region : NCR - National Capital Region Address : RCS Bldg III, Zapote, Alabang Road, Pamplona, Las Piñas City, City of Las Piñas, Fourth District Telephone : (02) 872-01-83; 872-61-62 Fax : (02) 872-02-20 E-mail : Year Established : 2001 Website : 1 Directory of Higher Education Institutions as of October 23, 2009 13308 ABE International College of Business and Accountancy-Quezon City Private Non-Sectarian President : Mr. Amable C. Aguiluz IX Region : NCR - National Capital Region Address : #878 Rempson Bldg., Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon City, Quezon City, Second District Telephone : (02) 912-95-77; 912-95-78 Fax : (02) 912-95-78 E-mail : Year Established : 2000 Website : 13350 ABE International College of Business and Accountancy-Taft Private Non-Sectarian President : Mr. -

List of Registered Serials and Publishers 2020

LIST OF REGISTERED SERIALS AND PUBLISHERS 2020 ISSN National Centre of the Philippines Bibliographic Services Division National Library of the Philippines LIST OF REGISTERED SERIALS AND PUBLISHERS 2020 ISSN 2599-5324 (CD) ISSN 2782-9561 (ONLINE) Prepared by: ISSN National Centre of the Philippines Bibliographic Services Division Published by: Research and Publications Division National Library of the Philippines CONTACT INFORMATION: ADDRESS: National Library of the Philippines T.M. Kalaw, Ermita, Manila 1000 TEL. NO.: (02) 5336-7200 / 5310-5056 / 5310-5035 loc. 406-407 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: web.nlp.gov.ph i BIBLIOGRAPHIC SERVICES DIVISION STAFF OIC, Librarian IV Jennifer B. Dimasaca Librarian III Marie Joy H. Bestoir Librarian II Romnic Henric Henry M. Gayanilo Librarian II Maria Loreta M. Go Librarian II Joel P. Lascano Librarian I Gabrielle Josephine M. Napao ii TABLE OF CONTENT Bibliographic Services Division Staff ii Table of Content iii Preface iv Introduction v Frequency vii List of Registered Serials 1 List of Online Journals 36 List of Publishers 39 iii PREFACE The International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) Directory is a list of Registered Serials and Publishers in the Philippines. The Directory is prepared annually by the Bibliographic Services Division. This 2020 annual accumulation consists of 295 number of serial and continuing resources. Serial and continuing resources title with different format have different ISSNs such as: Sample entry: The Bright Pen (title of the publication in printed format) Pamantasan ng -

School Calendar

New Era University No.9 Central Avenue, New Era, Quezon City 1107, Philippines Tel. No.: (632) 8981-4221 to 4231 | Fax: (632) 8981-4240 Web Site: www.neu.edu.ph ______________________________________________________________________ ACADEMIC CALENDAR FOR THE TERTIARY LEVEL FIRST SEMESTER, AY 2021 – 2022 DURATION: August 23, 2021 - December 23, 2021 July 1 – August 20 (T-F) = ENROLLMENT PERIOD August 19 (Th) = Special Holiday – Quezon Day August 21 (S) = Special Non-Working Day – Ninoy Aquino Day August 23 (M) = START OF CLASSES August 23 (M) = Last Day for Dissolution of Classes August 27 (F) = Last Day for Course Changes Due to Dissolved Classes August 30 (M) = Regular Holiday – National Heroes Day September 13 (M) = Start of Classes – CMD Levels 1 & 2 September 24 (F) = Last Day for Filing of Application for Graduation for Second Semester AY 2021-2022 Sept 27 – Oct.2 (M-S) = Preliminary Examinations - CMD Level 3 October 4 & 8 (M&F) = Post-Medicine Week Celebration (Presidential Proclamation No. 439) October 5 (T) = National Teachers’ Day (RA 10743) October 15 – 20 (F-W) = MID-TERM EXAMINATIONS October 18 – 23 (M-S) = Preliminary Examinations – CMD Levels 1 & 2 October 18 – 24 (M-Su) = Mid-Term Examinations – COL October 30 (S) = Last Day for Official Dropping of Courses – COL October 31 (Su) = Special Holiday – Church Holiday November 1 (M) = Special Non-Working Day November 2 (T) = Additional Special Non-Working Day November 8 – 13 (M-S) = Mid-Term Examinations – CMD Level 3 November 26 (F) = Last Day for Official Dropping of Courses Nov.27 – Dec.4 (S-S) = Mid-Term Examinations – CMD Levels 1 & 2 November 30 (T) = Regular Holiday – Bonifacio Day December 8 (W) = Special Non-Working Day December 13 – 18 (M-S) = Final Examinations – CMD Level 3 December 17 – 23 (F-Th) = FINAL EXAMINATIONS Dec.24 – Jan.16 (F-Su) = SEMESTRAL/HOLIDAY BREAK December 24 (F) = Additional Special Non-Working Day New Era University No.9 Central Avenue, New Era, Quezon City 1107, Philippines Tel. -

List of Recognized Institutions Updated: January 2017

Knowledge First Financial ‐ List of Recognized Institutions Updated: January 2017 To search this list of recognized institutions use <CTRL> F and type in some, or all, of the school name. Or click on the letter to navigate down this list: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 1ST NATIONS TECH INST-LOYALIST COLL Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory ON Canada 5TH WHEEL TRAINING INSTITUTE, NEW LISKEARD NEW LISKEARD ON Canada A1 GLOBAL COLLEGE OF HEALTH BUSINESS AND TECHNOLOG MISSISSAUGA ON Canada AALBORG UNIVERSITETSCENTER Aalborg Foreign Prov Denmark AARHUS UNIV. Aarhus C Foreign Prov Denmark AB SHETTY MEMORIAL INSTITUTE OF DENTAL SCIENCE KARNATAKA Foreign Prov India ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY Aberystwyth Unknown Unknown ABILENE CHRISTIAN UNIV. Abilene Texas United States ABMT COLLEGE OF CANADA BRAMPTON ON Canada ABRAHAM BALDWIN AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE Tifton Georgia United States ABS Machining Inc. Mississauga ON Canada ACADEMIE CENTENNALE, CEGEP MONTRÉAL QC Canada ACADEMIE CHARPENTIER PARIS Paris Foreign Prov France ACADEMIE CONCEPT COIFFURE BEAUTE Repentigny QC Canada ACADEMIE D'AMIENS Amiens Foreign Prov France ACADEMIE DE COIFFURE RENEE DUVAL Longueuil QC Canada ACADEMIE DE ENTREPRENEURSHIP QUEBECOIS St Hubert QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASS. ET D ORTOTHERAPIE Gatineau (Hull Sector) QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE ET D ORTHOTHERAPIE GATINEAU QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE DRUMMONDVILLE Drummondville QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE LANAUDIERE Terrebonne QC Canada ACADEMIE DE MASSAGE SCIENTIFIQUE QUEBEC Quebec QC Canada ACADEMIE DE SECURITE PROFESSIONNELLE INC LONGUEUIL QC Canada Knowledge First Financial ‐ List of Recognized Institutions Updated: January 2017 To search this list of recognized institutions use <CTRL> F and type in some, or all, of the school name. Or click on the letter to navigate down this list: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z ACADEMIE DECTRO INTERNATIONALE Quebec QC Canada Académie des Arts et du Design MONTRÉAL QC Canada ACADEMIE DES POMPIERS MIRABEL QC Canada Académie Énergie Santé Ste-Thérèse QC Canada Académie G.S.I. -

List of No Billing Statements Submission

LIST OF NO BILLING STATEMENTS SUBMISSION Source: PEAC National Secretariat (as of June 3, 2020) No. Region Private Higher Education Institution 1 Region 1 AMA Computer College-La Union 2 Region 1 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 3 Region 1 Data Center College of the Philippines-Vigan City 4 Region 1 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 5 Region 1 Divine Word College of Vigan 6 Region 1 Golden West Colleges 7 Region 1 La Finn's Scholastica 8 Region 1 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 9 Region 1 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 10 Region 1 Osias Educational Foundation 11 Region 1 Phinma-Upang College Urdaneta 12 Region 1 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 13 Region 1 PIMSAT Colleges-San Carlos City 14 Region 1 Saint Columban's College 15 Region 1 Saint Paul College of Ilocos Sur 16 Region 1 San Carlos College 17 Region 1 STI College-Vigan 18 Region 2 Northeastern College 19 Region 2 Sierra College 20 Region 3 Academia de San Lorenzo dema Ala 21 Region 3 ACLC College of Malolos, Inc. 22 Region 3 ACLC College of Meycauayan 23 Region 3 ACLC College of Sta. Maria 24 Region 3 ACLC College-Baliuag 25 Region 3 AMA Computer College-Angeles City 26 Region 3 Angeles University Foundation 27 Region 3 Aurora Polytechnic College 28 Region 3 Baliuag Maritime Academy 29 Region 3 Bestlink College of The Philippines-Bulacan 30 Region 3 Camiling Colleges Central Luzon College of Science and Technology-City of San Fernando Region 3 31 (Pampanga) 32 Region 3 Central Luzon College of Science and Technology-Olongapo City 33 Region 3 Central Luzon Doctors' Hospital Educational Institution 34 Region 3 Colegio de San Juan de Letran-Abucay 35 Region 3 Colegio de Sebastian-Pampanga 36 Region 3 College of Subic Montesorri-Dinalupihan 37 Region 3 Columban College-Sta. -

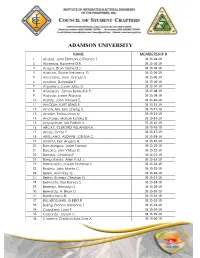

Adamson University Name Membership # 1

ADAMSON UNIVERSITY NAME MEMBERSHIP # 1. Abdon, John Emmanuel Francis T. 3S-15-01-19 2. Abrenica, Roxanne D.R. 3S-15-02-19 3. Alagar, David Elshe D.J. 3S-15-03-19 4. Alarcon, Glace Veronica G. 3S-15-04-19 5. Alcantara, John Joaquin S. 3S-15-05-19 6. Alcoriza, Dannielle P. 3S-15-06-19 7. Aligonero, Jason Julius O. 3S-15-07-19 8. Allauigan, James Benedick P. 3S-15-08-19 9. Alojado, Jason Alojado 3S-15-09-19 10. Alonzo, John Vincent E. 3S-15-10-19 11. AMODIA, KURT LEWIS E. 3S-15-11-19 12. Amon, Ma. Kim Cheng S. 3S-15-12-19 13. Ampler, Shelou Mae N. 3S-15-13-19 14. Anchores, Mariah Katrina B. 3S-15-14-19 15. Anyayahan, Ian Patrick V. 3S-15-15-19 16. ARCAY, CLEFORD VILLANUEVA 3S-15-16-19 17. Arcay, Omar Y. 3S-15-17-19 18. ARELLANO, ALDWIN JOSHUA C. 3S-15-18-19 19. Azanza, Ken Angelo A. 3S-15-19-19 20. Bacalangco, Justin Samuel 3S-15-20-19 21. Bacorro, Jims Vhiber D. 3S-15-21-19 22. Banday, Christian F. 3S-15-22-19 23. Bangalando, Allen Paul J. 3S-15-23-19 24. Barrameda,Joseph Nataniel v. 3S-15-24-19 25. Bedina, Jake Martin C. 3S-15-25-19 26. Belen, Alvin Rey G. 3S-15-26-19 27. Belino, Romeo Christian O. 3S-15-27-19 28. Belmonte, Kiel Harvey S. 3S-15-28-19 29. Bermejo, Remalyn S. 3S-15-29-19 30. -

SOM Qualified Applicants (AY 2021- 2022)

A Saint Louis University L I S T O F Q U A L I F I E D I N C O M I N G SCHOOL OF MEDICINE F R E S H M E N ( F I R S T B A T C H ) N Academic Year 2021-2022 I PLEASE PREPARE THE FOLLOWING AMOUNTS: S 1. APPLICATION PROCESSING FEE: I a. Filipino: PhP 3,330.00 (if not yet paid) b. Foreigner: $ 580.00 (if not yet paid) 2. RESERVATION FEE: a. PhP 50,000 D To all listed below, kindly sign the waiver sent to your e-mail addresses then send it to [email protected]. E Deadline for the payment of the Reservation fee of PhP 50,000 (deductible from 1st semester AY 2021 – 2022 tuition fee) is on or before April 19, 2021. You can pay your reservation fee on this link: https://slupaygway.slu.edu.ph/med/ M A V I V LIST OF QUALIFIED INCOMING FRESHMEN (FIRST BATCH) ABUAN, Kim S. Saint Louis University A AGUILAR, Angelica Mae B. Saint Louis University ALCANTARA, Almira Mae S. Saint Louis University ALCON, Cherry Lyn M. University of the Philippines Los Banos ALSIKEN, Josabel B. Benguet State University ANDRADA, Eddie Greg D. New Era University N ANGELES, John Gwire M. Saint Louis University AQUIEN, Wenchille A. Saint Louis University I AQUINO, Adelede P. University of the Philippines Los Banos AQUINO, Roze anne Nicole R. Saint Louis University ARAGON, Miguel IV R. Saint Louis University S ARANCA, Measy Faith L. Saint Louis University AYBAN, Shielynne Khale M. -

GENERAL ASSEMBLY and INDUCTION/AWARDING CEREMONIES by Kaori B

PHILIPPINE ASSOCIATION OF ACADEMIC/RESEARCH LIBRARIANS, INC. NO. 1 JANUARY — M A R C H 2 0 1 5 ISSN - 0116- 14 nd 42 GENERAL ASSEMBLY AND INDUCTION/AWARDING CEREMONIES By Kaori B. Fuchigami INSIDE THIS ISSUE: 42nd General Assembly and Dr. Elizabeth Q. Lahoz, President, Technological Institute of the Philippines with the Induction / Awarding Cere- 1 newly elected members of the board as they take their oath. monies By Kaori B. Fuchigami he Philippine Associa- University-Diliman) ; Secretary, to work on the following priority 2015 PAARL Executive 3 tion of Academic/ Willian S.A. Frias (De La Salle needs of the association: Board Research Librarians University) ; Treasurer, Estela A. Increase advocacy and mar- nd Upholding PAARL’s Dream held its 42 General Montejo ( Ateneo de Manila Uni- keting of the Association Amidst Current Issues and T 4 Assembly and Induction/ versity Rizal Library) ; Auditor, Develop and manage the Trends Awarding Ceremonies last Janu- Aniline A. Vidal (University of By Maribel A. Estepa Association’s financial re- ary 30, 2015 at the Technological Perpetual Help System DAL- sources Inspirational Messege 7 Institute of the Philippines- TA) ; Public Relations Officer, By Dr. Elizabth Q. Lahoz Work on promoting the or- Manila. The keynote speaker on Kaori B. Fuchigami (University ganization towards increased President’s Report 8 this significant event was the of Santo Tomas Miguel de Be- By Sharon Maria S. Esposo-Betan membership president of the Technological navides Library) ; Directors, Continue with the publica- 2014 Audited Finalcial Re- Institute of the Philippines, Dr. Rosela D. Del Mundo (Jose Rizal 13 tion of the PAARL Research port Elizabeth Quirino-Lahoz.