The Management of Lithic Resources During the V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extensión De La Banda Ancha En La Provincia De Huesca Listado De

Extensión de la banda ancha en la provincia de Huesca Listado de núcleos UNIÓN EUROPEA Extensión banda ancha en la provincia de Huesca Listado de las 321 entidades singulares de población sobre las que actuará la Diputación Provincial de Huesca dentro del Plan de Extensión de la Banda Ancha Comarca Municipio Núcleo Alto Gállego Biescas Aso de Sobremonte Alto Gállego Biescas Escuer Alto Gállego Biescas Oliván Alto Gállego Biescas Orós Alto Alto Gállego Biescas Orós Bajo Alto Gállego Biescas Yosa de Sobremonte Alto Gállego Caldearenas Anzánigo Alto Gállego Caldearenas Aquilué Alto Gállego Caldearenas Javierrelatre Alto Gállego Caldearenas Latre Alto Gállego Caldearenas San Vicente Alto Gállego Hoz de Jaca Hoz de Jaca Alto Gállego Panticosa Panticosa Alto Gállego Panticosa Pueyo de Jaca (El) Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Artosilla Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Aurín Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Cartirana Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Ibort Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Isún de Basa Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Lárrede Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Larrés Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Latas Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Osán Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Pardinilla Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Puente de Sabiñánigo (El) Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Sabiñánigo Alto Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Sardas Alto Gállego Sabiñánigo Sorripas Alto Gállego Sallent de Gállego Escarrilla Alto Gállego Sallent de Gállego Formigal Alto Gállego Sallent de Gállego Lanuza Alto Gállego Sallent de Gállego Sallent de Gállego Alto Gállego Sallent de Gállego Sandiniés Alto Gállego Yebra de Basa Yebra de Basa Bajo Cinca Ballobar Ballobar -

Mapa Sanitario Comunidad Autónoma De Aragón

MAPA SANITARIO COMUNIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE ARAGÓN DIRECCIÓN DEL DOCUMENTO MANUEL GARCÍA ENCABO Director General de Planificación y Aseguramiento Departamento de Salud y Consumo JULIÁN DE LA BÁRCENA GUALLAR Jefe de Servicio de Ordenación y Planificación Sanitaria Dirección General de Planificación y Aseguramiento Departamento de Salud y Consumo ELABORACIÓN MARÍA JOSÉ AMORÍN CALZADA Servicio de Planificación y Ordenación Sanitaria Dirección General de Planificación y Aseguramiento Departamento de Salud y Consumo OLGA MARTÍNEZ ARANTEGUI Servicio de Planificación y Ordenación Sanitaria Dirección General de Planificación y Aseguramiento Departamento de Salud y Consumo DIEGO JÚDEZ LEGARISTI Médico Interno Residente de Medicina Preventiva y Salud Pública Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa AGRADECIMIENTOS Se agradece la colaboración prestada en la revisión de este documento a Javier Quíntin Gracia de la Dirección de Atención Primaria del Servicio Aragonés de Salud, y a María Luisa Gavín Lanzuela del Instituto Aragonés de Estadística. Además, este documento pretende ser continuación de la labor iniciada hace años por compañeros de la actual Dirección de Atención Primaria del Servicio Aragonés de Salud. Zaragoza, septiembre de 2004 Mapa Sanitario de Aragón 3 ÍNDICE ORGANIZACIÓN TERRITORIAL.................................................................... 5 SECTOR DE BARBASTRO ........................................................................................................ 13 SECTOR DE HUESCA ............................................................................................................. -

Sin Título-2

� � L PROGRAMA DE AYUDAS � � � � EUROPEO PRODER DESPIERTA � � � � � GRAN INTERÉS EN EL MUNICIPIO � � � E Está dotado con seis millones de euros. � � � cón aprovecharse de los fondos � PRODER (Programa de Diversi- � ficación Económica –Rural). � � El programa está impulsado � por las comarcas del Bajo Cinca, Cinca Medio y Litera y ha sido aprobado por el Departamento de Agricultura del la Diputación General de Aragón y dotado con seis millones de euros. La Agencia de Empleo y De- sarrollo Rural de Altorricón está El Ayuntamiento de Altorricón apro- recibiendo una gran afluencia de perso- bó por unanimidad apoyar la solicitud nas y empresas interesadas en solicitar de CEDER-ZONA ORIENTAL, proyec- información sobre el programa. to que permite a los vecinos de Altorri- (continúa pág. 5) PEDRO SANZ, GANADOR DEL CARTEL DE LAS FIESTAS MAYORES 2002 El oscense, Pedro Sanz Vitalla, ha si- Sanz Vitalla, se ha presentado a otros do el ganador del concurso del cartel concursos y ha obtenido algunos premios anunciador de las Fiestas Mayores de como fue, el cartel anunciador de las Fies- Altorricón 2002, dotado con 150 euros. tas Mayores de Alcalá de Gurrea, el logoti- � Sanz Vitalla, tiene 27 años y es ad- po de la Concejalía de Cultura del Ayunta- � � miento de Picassent (Valencia) entre otros. � ministrativo de profesión. En su tiempo � � libre se dedica al diseño gráfico, además � � de la pintura al óleo y acuarela. � El autor define el cartel como una � obra colorista “me he centrado en las � raíces de Altorricón, lo más solariego � � pero vistiéndolos de gala para que � tuviera un toque más festivo, además de � � los fuegos artificiales que son también � � parte de cualquier fiesta”. -

La Cueva De Chaves: Estudio De La Organización Microespacial Durante El Neolítico the Cave of Chaves: Microspatial Distribution in Neolithic

SALDVIE n.º 15 2015 pp. 35-51 La cueva de Chaves: estudio de la organización microespacial durante el Neolítico The cave of Chaves: microspatial distribution in Neolithic Pilar Sánchez Cebrián* Resumen El estudio pretende mostrar una aproximación general de la distribución microespacial de los objetos hallados en la cueva de Chaves en sus dos niveles neolíticos, Ib (cardial) y Ia (cardial final). Los materiales se han dividido en dos categorías, una mayor (compuesta por restos de fauna, cerámica e industria lítica) que dibuja y muestra las concentraciones mediante curvas de isodensidades; y cinco agrupaciones menores (industria ósea, adornos, cantos con ocre, minerales y restos vegetales) que se reflejan sobre las plantas de la cueva mediante símbolos. El objetivo principal es contribuir a completar la información sobre la cavidad y conocer el espacio doméstico mediante las zonas «habitadas» de la cueva de Chaves en su cronología neolítica a través de la dispersión que ofrecen los restos arqueológicos. Palabras clave: Distribución microespacial. Cueva de Chaves. Neolitico. Abstract This essay intends to explain a general approximation of the microspatial distribution at the cave of Chaves. Using the materials found in his two neolithic levels, Ib (cardial) and Ia (cardial end). The materials have been divided in two categories, the big ones (composed by remains of animals´ bones, pottery and lithic industry) that draws the concentrations of curves of isodensities; and five minor groups (bone industry, jewlery, ocher painted blocks, minerals and vegetable remains) that are reflected on the ground through symbols. The main objective is to expand the information about the cave. -

Relación De Las Coordenadas UTM, Superficie Municipal, Altitud Del Núcleo Capital De Los Municipios De Aragón

DATOS BÁSICOS DE ARAGÓN · Instituto Aragonés de Estadística Anexo: MUNICIPIOS Relación de las coordenadas UTM, superficie municipal, altitud del núcleo capital de los municipios de Aragón. Superficie Altitud Municipio Núcleo capital Comarca Coordenada X Coordenada Y Huso (km 2) (metros) 22001 Abiego 22001000101 Abiego 07 Somontano de Barbastro 742146,4517 4667404,7532 30 38,2 536 22002 Abizanda 22002000101 Abizanda 03 Sobrarbe 268806,6220 4680542,4964 31 44,8 638 22003 Adahuesca 22003000101 Adahuesca 07 Somontano de Barbastro 747252,4904 4670309,6854 30 52,5 616 22004 Agüero 22004000101 Agüero 06 Hoya de Huesca / Plana de Uesca 681646,6253 4691543,2053 30 94,2 695 22006 Aísa 22006000101 Aísa 01 La Jacetania 695009,6539 4727987,9613 30 81,0 1.041 22007 Albalate de Cinca 22007000101 Albalate de Cinca 08 Cinca Medio 262525,9407 4622771,7775 31 44,2 189 22008 Albalatillo 22008000101 Albalatillo 10 Los Monegros 736954,9718 4624492,9030 30 9,1 261 22009 Albelda 22009000101 Albelda 09 La Litera / La Llitera 289281,1932 4637940,5582 31 51,9 360 22011 Albero Alto 22011000101 Albero Alto 06 Hoya de Huesca / Plana de Uesca 720392,3143 4658772,9789 30 19,3 442 22012 Albero Bajo 22012000101 Albero Bajo 10 Los Monegros 716835,2695 4655846,0353 30 22,2 408 22013 Alberuela de Tubo 22013000101 Alberuela de Tubo 10 Los Monegros 731068,1648 4643335,9332 30 20,8 352 22014 Alcalá de Gurrea 22014000101 Alcalá de Gurrea 06 Hoya de Huesca / Plana de Uesca 691374,3325 4659844,2272 30 71,4 471 22015 Alcalá del Obispo 22015000101 Alcalá del Obispo 06 Hoya de Huesca -

Provincia De HUESC A

Provincia de HUESC A Comprende esta provincia los siguientes municipios, por partldosjudlciale s Partido de Barbastro Partido de Boltaña Abiego . Hoz de Barbastroe Abizanda . Laguarta . Adahuesca . Huerta de Vero . Aínsa. Laspuña. Alberuela de la Llena . Ilche . Albella y Jánovas . Linás de Broto . Alfántega. Laluenga . Arcusa . Mediano. Alquézar. Laperdiguera . Bárcabo . Morillo de Monclús . Azara . Lascellas . Benasque . Muro de Roda . Azlor . Mipanas . Bergua-Basarán . Olsón . Barbastro . Monzón. Bielsa . Palo. Barbuñales. Naval . Bisaurri . Plan. Berbegal . Peraltilla. Boltaña . Puértolas . Bierge. Pomar. Broto Pueyo de Araguás (El) . Buera. Ponzano . Burgasé. Rodellar . Castejón del Puente . Pozán de Vero . Campo . Sahún . Castillazuelo . Pueyo de Santa Cruz_ Castejón de Sobrarbe . San Juan de Plan . Colungo . Radiquero. Castejón de Sos . Santa María de Buil . Coscojuela de Fantova . Salas Altas. Ciamcsa . Sarsa de Surta. Costeán. Salas Bajas . Cortinas . Seira . Cregenzán . Salinas de Hoz. Coscojuela de Sobrarbe. Sesué . Fonz . Selgua . Chía . Siesta. Grado (El). Fanlo. Sin y Salinas. Fiscal . Talla . Partido de Benabarre Foradada de Tascar. Toledo de Lanata . Gerbe y Griébal . Torta . Aguinaliu . Merli . Gistain . Valle de Bardagí . Arén . Monesma de Benabarre. Guaso . Valle de Lierp. Benabarre . Montanúy. Labuerda . Villanova . Beranúy . Neril. Betesa . Olvena. Partido de Fraga Bonansa . Panillo . Bono . Perarrúa . AlbaIate de Cinca . Fraga . Cajigar. Pilzán . Alcolea de Cinca . Ontiñena . Caladrones . Puebla de Castro (La) . Ballobar . Osso. Calvera. Puebla de Fantova (La). Belver. Peñalba . Capella . Puebla de Roda (La) . Binaced . Torrente de Cinca . Caseras del Castillo . Puente de Montañana . Candasnos . Valfarta . Castanesa . Purroy de la Solana . Chalamera. Velilla de Cinca . Castigaleu. Roda de Isábena. Esplús . Zaidín. Cornudella de Baliera . Santa Liestra y San Qullez. Espés . Santoréns . Partido de Huesc a Fel . -

3. Cueva De Chaves .87 3.1

NICCOLÒ MAZZUCCO The Human Occupation of the Southern Central Pyrenees in the Sixth-Third Millennia cal BC: a Traceological Analysis of Flaked Stone Assemblages TESIS DOCTORAL DEPARTAMENT DE PREHISTÒRIA FACULTAT DE LETRES L Director: Dr. Ignacio Clemente-Conte Co-Director: Dr. Juan Francisco Gibaja Bao Tutor: Dra. Maria Saña Seguí Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2014 This work has been founded by the JAE-Predoc scholarship program (year 2010-2014) of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), realized at the Milà i Fontanals Institution of Barcelona (IMF). This research has been carried out as part of the research group “Archaeology of the Social Dynamics” (Grup d'Arqueologia de les dinàmiques socials) of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology of the IMF. Moreover, the author is also member of the Consolidated Research Group by the Government of Catalonia “Archaeology of the social resources and territory management” (Arqueologia de la gestió dels recursos socials i territori - AGREST 2014-2016 - UAB-CSIC) and of the research group “High-mountain Archaeology” (Grup d'Arqueologia d'Alta Muntanya - GAAM). 2 Todos los trabajos de arqueología, de una forma u otra, se podrían considerar trabajos de equipo. Esta tesis es el resultado del esfuerzo y de la participación de muchas personas que han ido aconsejándome y ayudándome a lo largo de su desarrollo. Antes de todo, quiero dar las gracias a mis directores, Ignacio Clemente Conte y Juan Francisco Gibaja Bao, por la confianza recibida y, sobre todo, por haberme dado la posibilidad de vivir esta experiencia. Asimismo, quiero extender mis agradecimientos a todos los compañeros del Departamento de Arqueología y Antropología, así como a todo el personal de la Milà i Fontanals. -

Anuncio De La Apertura De Cobranza

7 Julio 2020 Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de Huesca Nº 128 SELLO ADMINISTRACIÓN LOCAL DIPUTACIÓN PROVINCIAL DE HUESCA 07/07/2020 TESORERÍA RECAUDACION DE TRIBUTOS SERVICIOS CENTRALES Publicado en tablón de edictos 2335 ANUNCIO APERTURA DE COBRANZA DEL IMPUESTO SOBRE VEHÍCULOS DE TRACCIÓN MECÁNICA, IMPUESTO SOBRE BIENES INMUEBLES DE NATURALEZA URBANA Y DE CARACTERÍSTICAS ESPECIALES, AÑO 2020 Y TASAS Y PRECIOS PÚBLICOS, SEGUNDO PERÍODO DE RECAUDACIÓN AÑO 2020 . De conformidad con los artículos 23 y 24 del Reglamento General de Recaudación, aprobado por Real Decreto 939/2005, de 29 de julio, se pone en conocimiento de los contribuyentes, que desde el próximo día 15 de julio y hasta el día 19 de octubre de 2020, se con ambos inclusive, tendrá lugar la cobranza anual, por recibo, en período voluntario, del firma Sede no la IMPUESTO SOBRE VEHÍCULOS DE TRACCIÓN MECÁNICA (AÑO 2020), IMPUESTO una que en y SOBRE BIENES INMUEBLES DE NATURALEZA URBANA Y DE CARACTERÍSTICAS documento CSV menos ESPECIALES (AÑO 2020) Y DE TASAS Y PRECIOS PÚBLICOS de los conceptos, el el al períodos y ayuntamientos que se especifican, con arreglo al calendario que se publica en el con Electrónica Boletín Oficial de la Provincia y en los Edictos que se remitirán por el Servicio Provincial de obtener contiene Recaudación de Tributos Locales para su exposición en el Tablón de anuncios de los Sede acceda la respectivos Ayuntamientos. necesita de original Si originales, Ayuntamientos de los que se realiza el cobro del fuera Impuesto sobre Vehículos de Tracción validar. Mecánica (año 2020): documento firmas El realizada pudo las Electrónica. -

P R O V in C Ia D E H U Esc A

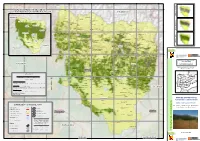

630 660 690 720 750 780 810 A C I F Á R G O 4750 4750 P O ANSO T MAPA DE DISTRIBUCIÓN DEL HÁBITAT D A D DE LA TRUFA NEGRA EN LA PROVINCIA DE HUESCA I FRANCIA L A I C N E T O P NAVARRA SALLENT DE GALLEGO CANFRANC BORAU PANTICOSA A C I JACETANIA VALLE DE HECHO T ARAGÜES DEL PUERTO Á M I AISA-CANDANCHU L C JASA HOZ DE JACA TORLA BIELSA D GISTAIN A SOBRARBE VILLANUA D ALTO I GÁLLEGO L A BENASQUE I C N SAN JUAN DE PLAN E BORAU T YESERO CASTIELLO DE JACA BIESCAS O SAHUN P RIBAGORZA TELLA-SIN 47 FANLO 47 20 CANAL DE BERDUN 20 HOYA DE HUESCA PUENTE LA REINA DE JACA BROTO PUERTOLAS SOMONTANO VILLANOVACASTEJON DE SOS MONTANUY A PLAN C DE Jaca SESUE I SANTA CILIA DE JACA F BARBASTRO Á D JACA CHIA E SANTA CRUZ DE LA SEROS LASPUÑA D A SEIRA D I PUEYO DE ARAGUAS BISAURRI L LA LITERA A I CINCA BAILO YEBRA DE BASA FISCAL C N MEDIO LASPAULES E T MONEGROS O LABUERDAPUEYO DE ARAGUAS P CAMPO VALLE DE BARDAJI BONANSA LLEIDA FORADADA DEL TOSCAR BOLTAÑA Aínsa VALLE DE LIERP VERACRUZ ZARAGOZA BAJO CINCA CALDEARENAS TORRE LA RIBERA LAS PEÑAS DE RIGLOS SABIÑANIGO LA FUEVA SOPEIRA AINSA-SOBRARBE 46 PALO SANTA LIESTRA Y SAN QUILEZ 46 90 ISABENA 90 ARGUIS AREN AGÜERO LOARRE NUENO PERARRUA ABIZANDA BARCABO BIERGE MONESMA Y CAJIGAR MAPA DE APTITUD PARA EL CULTIVO LA SOTONERA AYERBE CASBAS DE HUESCA DE LA TRUFA NEGRA ADAHUESCA CASTIGALEU LOSCORRALES LOPORZANO (Tuber melanosporum Vittad.) NAVAL SECASTILLA LASCUARRE NAVARRA IGRIES Graus BISCARRUES CAPELLA EN LA PROVINCIA DE HUESCA COLUNGO PUENTE DE MONTAÑANA BANASTAS ALQUEZAR CHIMILLAS HOZ Y COSTEAN Juan Barriuso ; Roberto -

Efectuados a Cada Entidad Local En El Año 2015 | 374.804

IMPORTE DE LOS ANTICIPOS POR RECAUDACIÓN VOLUNTARIA EFECTUADOS A CADA ENTIDAD LOCAL EN EL AÑO 2015 ORDENADO DE MAYOR A MENOR IMPORTE ORDEN ENTIDAD LOCAL ANTICIPO 1 HUESCA 11.558.421,02 2 JACA 5.218.927,75 3 FRAGA 3.522.889,39 4 MONZÓN 3.419.984,76 5 BARBASTRO 3.274.747,95 6 SABIÑANIGO 2.512.169,93 7 BINEFAR 2.398.553,74 8 SARIÑENA 1.129.404,10 9 BENASQUE 1.117.280,22 10 TAMARITE DE LITERA 895.363,59 11 BIESCAS 889.356,24 12 ALMUDEVAR 828.483,28 692.642,28 13 IMONTANUY | 624.031,38 14 GRAUS i 607.103,20 15 AINSA-SOBRARBE : 16 COMARCA DE LA RIBAGORZA 507.000,00 17 PANTICOSA 504.777,82 18 ¡GRANEN 495.811,94 19 ALCALÁ DE GURREA 478.468,86 20 AISA 442.677,58 418.487,61 21 TARDIENTA : 411.717,17 22 GURREA DE GALLEGO i 374.804,43 23 CANFRANC | 24 VILLANUA 373.098,22 25 COMARCA DE LOS MONEGROS 370.000,00 26 BOLTAÑA 323.445,47 27 LUPINEN-ORTILLA 317.094,85 313.037,64 28 FUE VA, LA : 312.060,71 29 LALUEZA | ÍALTORRICON 307.790,26 31 ILANAJA 305.360,07 32 IFONZ 287.314,62 33 IGRADO, EL 281.621,63 IMPORTE DE LOS ANTICIPOS POR RECAUDACIÓN VOLUNTARIA EFECTUADOS A CADA ENTIDAD LOCAL EN EL AÑO 2015 ORDENADO DE MAYOR A MENOR IMPORTE ORDEN ENTIDAD LOCAL ANTICIPO 34 ¡ZAIDIN 262.860.52 35 ICOMARCA DE LA JACETANIA 261.000.00 36 ICASTEJON DE SOS 260.176,70 DE CINCA 260.029,64 38 ,AYERBE 252.477,76; 39 ESPLUS 227.025,01 40 BINACED 218.566,13 41 BIELSA 217.968,66 42 ¡SAN MIGUEL DEL CINCA 216.495,17 43 ¡SOTONERA, LA 213.147,22j 44 ÍVIACAMP Y LITERA 206.606,84 45 ¡CAMPO 205.772,82 46 BELVER DE CINCA 194.446,99 SE CASTILLA 47 ! 192.926,32 48 ¡ESTAD ILLA 190.166,81 -

Graduados Altoaragoneses En Las Facultades De Leyes Y Canones De La Universidad De Huesca

GRADUADOS ALTOARAGONESES EN LAS FACULTADES DE LEYES Y CANONES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE HUESCA José MF LAHQZ FINESTRES La Universidad de Huesca fue fundada en 1354 por Pedro IV de Aragón, quien satisfacía así una petición del municipio oscense. El examen de la documentación de aquella época indica que el Estudio General se Cerro poco tiempo después de su fun- dacion, de modo que fue necesario refundar el Centro en 1465. En este ano la Universidad obtuvo, entre otros apoyos, el refrendo del Papa Pablo II. Esta confirma- cion pontificia fue decisiva para el Estudio General de Huesca, ya que comenzó a reci- bir el apoyo de la Iglesia. Así, esta aporto rentas eclesiásticas que fueron fundamenta- les para garantizar la existencia de la Universidad. No obstante, parece que el Estudio estuvo debilitado hasta bien entrado el siglo XVI. Los pocos documentos que se con- servan indican que tanto el numero de profesores como el de alumnos era muy bajo. Además, apenas hay noticias sobre quiénes eran éstos. La Universidad Sertoriana se afiancé durante el siglo XVI, tal como lo prueba la aportación de nuevas rentas eclesiásticas, el incremento de profesores y graduados, la consolidación de los colegios religiosos de los conventos de la Ciudad o la fundación de los primeros colegios seculares. Desde esta centuria la Universidad oscense funcio- n6 de una manera casi inintemimpida. Se mantuvo durante el siglo XVII a pesar de las 108 José Mb* LA1-[oz FINESTRES calamidades. El siglo XVIII fue, en muchos aspectos, una época de esplendor. En el siglo XIX tuvo una actividad modesta hasta su clausura en 1845 como consecuencia de la aplicación del Plan Pidal. -

COMUNIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE ARAGÓN Zonas Vulnerables a La

Dirección General de Calidad y COMUNIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE ARAGÓN Seguridad Alimentaria Zonas Vulnerables a la contaminación de las aguas por nitratos Orden AGM/83/2021 Ansó Ansó Sallent de Gállego Canfranc Panticosa Fago Valle de Hecho Aragüés del Puerto Aísa Jasa Hoz de Jaca Gistaín Villanúa Torla-Ordesa Bielsa Salvatierra de Esca Borau Benasque Castiello de Jaca Biescas Yésero San Juan de Plan Sahún Tella-Sin Sigüés Canal de Berdún Fanlo Artieda Puente la Reina de Jaca Broto Puértolas Undués de Lerda Mianos Plan Sesué Montanuy Santa Cilia Villanova Chía Castejón de Sos Los Pintanos Jaca Urriés Bagüés Santa Cruz de la Serós Laspuña Seira Bisaurri Laspaúles Navardún Bailo Yebra de Basa Fiscal Isuerre Labuerda Longás El Pueyo de Araguás Lobera de Onsella Sabiñánigo Valle de Bardají Sos del Rey Católico Bonansa Boltaña Foradada del Toscar Las Peñas de Riglos Caldearenas Valle de Lierp Beranuy La Fueva Sopeira Biel Aínsa-Sobrarbe Castiliscar Uncastillo Luesia Santaliestra y San Quílez Murillo de Gállego Palo Isábena Agüero Loarre Arguis Arén Nueno Layana Perarrúa El Frago Abizanda Bárcabo Monesma y Cajigar Sádaba Asín Bierge Orés Santa Eulalia de Gállego Ayerbe La Sotonera Biota Adahuesca Castigaleu Loscorrales Loporzano Graus Lascuarre Igriés Casbas de Huesca Naval Secastilla Biscarrués Capella Puente de Montañana Colungo Ardisa Chimillas Lupiñén-Ortilla Ibieca Tolva LunaValpalmas Alerre Quicena Abiego El Grado La Puebla de Castro Puendeluna Siétamo Hoz y Costeán Huesca Tierz Salas Altas Ejea de los Caballeros Piedratajada Azlor Benabarre Viacamp