STRIKE a Live History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Book Compares Resistance to Technology Across Time, Nations and Tech- Nologies

This book compares resistance to technology across time, nations and tech- nologies. Three post-war technologies - nuclear power, information technology and biotechnology - are used in the analysis. The focus is on post-1945 Europe, with comparisons made with the USA, Japan and Australia. Instead of assuming that resistance contributes to the failure of a technology, the main thesis of this book is that resistance is a constructive force in technological development, giving technology its particular shape in a particular context. Whilst many people still believe in science and technology, many have become more sceptical of the allied 'progress'. By exploring the idea that modernity creates effects that undermine its own foundations, forms and effects of resistance are explored in various contexts. The book presents a unique interdisciplinary study, including contributions from historians, sociologists, psychologists and political scientists. Resistance to new technology Resistance to new technology nuclear power information technology and biotechnology edited by MARTIN BAUER The National Museum WigRTof Science & Industry Science Museum 31 CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building. Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1995 This book is in copyright. -

Trade Union Collective Identity, Mobilisation and Leadership – a Study of the Printworkers’ Disputes of 1980 and 1983

Trade Union collective identity, mobilisation and leadership – a study of the printworkers’ disputes of 1980 and 1983 Nigel Costley 1 2 University of the West of England Collective identity and strategic choice – a study of the printworkers’ disputes of 1980 and 1983 Nigel Costley A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bristol Business School, University of the West of England 2021 3 Declaration I declare that this research thesis is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Nigel Costley Date 4 Copyright This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements Thanks to Professor Stephanie Tailby, Professor Sian Moore and Dr Mike Richardson for their continuous encouragement, support and constructive criticisms. 5 Abstract The National Graphical Association (NGA) typified the British model of craft unionism with substantial positional power and organisational strength. This study finds that it relied upon, and was reinforced by, the common occupational bonds that members identified with. It concludes that the value of collective identity warrants greater attention in the debate over union renewal alongside theories around mobilisation and organising (Kelly 2018), alliance-building and social movements (Holgate 2014). Sectionalism builds solidarity through the exclusion of others. Occupational identity is vulnerable to technological change. This model neglects institutional and ‘associational’ power, eschewing legal protections in favour of collective bargaining and ignoring alliance-building in favour of sovereign authority. -

Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers

ID Heading Subject Organisation Person Industry Country Date Location 74 JIM GARDNER (null) AMALGAMATED UNION OF FOUNDRY WORKERS JIM GARDNER (null) (null) 1954-1955 1/074 303 TRADE UNIONS TRADE UNIONS TRADES UNION CONGRESS (null) (null) (null) 1958-1959 5/303 360 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS NON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS (null) (null) (null) 1942-1966 7/360 361 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS NOW ASSOCIATIONON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS N(null) (null) (null) 1967 TO 7/361 362 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS CONFERENCES NONON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS N(null) (null) (null) 1955-1966 7/362 363 ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS IN TECHNICAL INSTITUTIONS APPRENTICES ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS IN TECHNICAL INSTITUTIONS (null) EDUCATION (null) 1964 7/363 364 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1929-1935 7/364 365 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1935-1962 7/365 366 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1963-1970 7/366 367 BRITISH AIR LINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH AIR LINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION (null) TRANSPORT CIVIL AVIATION (null) 1969-1970 7/367 368 CHEMICAL WORKERS UNION CONFERENCES INCOMES POLICY RADIATION HAZARD -

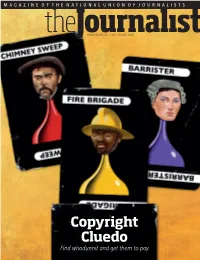

Copyright Cluedo Find Whodunnit and Get Them to Pay Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | JULY-AUGUST 2018 Copyright Cluedo Find whodunnit and get them to pay Contents Main feature 12 Close in and win The quest for copyright justice News opyright has been under sustained 03 STV cuts jobs and closes channel attack in the digital age, whether it is through flagrant breaches by people Pledge for no compulsory redundancies hoping they can use photos and 04 Call for more disabled people on TV content without paying or genuine NUJ backs campaign at TUC conference Cignorance by some who believe that if something is downloadable then it’s free. Photographers 05 Legal action to demand Leveson Two and the NUJ spend a lot of time and energy chasing copyright. Victims get court go-ahead This edition’s cover feature by Mick Sinclair looks at a range of 07 Al Jazeera staff win big pay rise practical, good-spirited ways of making sure you’re paid what Deal reached after Acas talks you’re owed. It can take a bit of detective work. Data in all its forms is another big theme of this edition. “Whether it’s working within the confines of the new general Features data protection regulations or finding the best way to 10 Business as usual? communicate securely with sources, data is an increasingly What new data rules mean for the media important part of our work. Ruth Addicott looks at the implications of the new data laws for journalists and Simon 13 Safe & secure Creasey considers the best forms of keeping communication How to communicate confidentially with sources private. -

The Marxist Volume: 13, No

The Marxist Volume: 13, No. 01 Jan-March 1996 (Extract From Making of the Black Working Class in Britain) Saklatvala played a glorious role as one of the pioneers of the international working class movement. If, as Lenin said, `Capital is an international force. Its defeat requires an international brotherhood', then Saklatvala symbolised such an international brotherhood of workers. R. Palme Dutt recognised him as a heroic figure who fought on many fronts: for international communism, for Indian national liberation and for the causes of the British working class movement. Indeed, he became the first Indian to be accepted and loved by British workers. His development from capitalism to Communism reflects a spiritual odyssey. From a wealthy family background, he was able to make a passionate commitment towards finding a means to end the poverty and misery of the masses in India. As he told Palme Dutt, there were four stages in this spiritual odyssey. First he sought in religion the key that would unlock the door to a new awakening and advance of the nation. He realised, however, that instead of providing a solution, religion led only to passivity and a sanctifying of the existing unacceptable order of society. Second, he turned to science as a means of helping the Indian people. After years of scientific studies (and having been an active welfare worker in the plague hospitals and slums of Bombay) he found that science alone offered no solution unless it was applied in practice to the economy. Third, he felt that in order to end Indian poverty, industrial development was necessary. -

A REPLY to MARTIN SHAW Ian H. Birchall

THE PREMATURE BURIAL: A REPLY TO MARTIN SHAW Ian H. Birchall Martin Shaw's 'unofficial' history of the International Socialists1 makes an important contribution to the debate that has been taking place, over the last few years, in the pages of The Socialist Register about the sort of organization that the British left needs. Shaw has written, firmly if not without melancholy, an obituary for the political tendency represented by the International Socialists and (since 1977) the Socialist Workers Party. By 1976, Shaw tells us, the organization was 'radically deformed'; its politics had become 'opportunistic, unrealistic and sectarian'; its 'degeneration' repre- sented a 'squandering of the potential for a new socialist movement'; it had undergone 'catastrophic changes'.* These are serious charges and require a cool and objective response. Every failure has its lessons and every defeat is a stepping-stone to final victory. For example, the IS/SWP represents the most serious and consistent attempt in recent years to build a revolutionary socialist organization outside of and independent from the Labour Party. An acceptance of Shaw's case would be a strong argument on the side of those who believe that Marxists must continue to work within the Labour Party. Moreover, any SWP member who reads Shaw's article will be willing to concede that some of Shaw's specific criticisms are at least partially correct. All the more pity that Shaw frames them in the context of an article which uses the weaknesses as the proof of irredeemable corruption rather than asking how they may best be corrected. Shaw makes a wide range of criticisms, but behind them lie two fundamental points: firstly, that the IS/SWP has failed to develop an adequate form of internal democracy; secondly, that the IS/SWP is guilty of a political deviation described as 'workerism'. -

Faces of Non-Union Representation in the UK: Management Strategies, Processes and Practice

Paul J. Gollan Faces of non-union representation in the UK: management strategies, processes and practice Conference Paper Original citation: Originally presented at Industrial Relations Association World Congress, 8-12 September 2003, Berlin. This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/20456/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2008 A later version of this paper was published in International employment relations review, 9 (2), 2003. © 2003 Paul J. Gollan LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. Special Seminar - New Forms of Organisation, Partnership and Interest Representation International Industrial Relations Association World Congress Berlin, 8-12 September, 2003 Faces of non-union representation in the UK – Management strategies, processes and practice Paul J. Gollan Draft Only Department of Industrial Relations London School of Economics Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE Email: [email protected] (No part of this paper is to be cited without prior permission) 1 Faces of non-union representation in the UK – Management strategies, processes and practice This paper will attempt to examine non-union employee representation1 (NER) structures in the UK and, in particular assess management strategies, processes and practice of NER arrangements in nine organisations. -

Political Pseudonyms

BRITISH POLITICAL PSEUDONYMS Suggested additions and corrections always welcome 20th CENTURY Adler, Ruth Ray Waterman Ajax Montagu Slater [in Left Review, which he helped create & edited in 1934] Ajax Junior Guy A Aldred (in the Agnostic Journal). Allen, C Chimen Abramsky [CP National Jewish Committee] Allen, Peter Salme Dutt [née Murrik aka Pekkala; married to Rajani Palme Dutt] Anderson, Irene Constance Haverson [George Lansbury's granddaughter, Comintern courier] Andrews, R F Andrew Rothstein [CPGB] Arkwright, John Randall Swingler [CP writer] Ashton, Teddy Charles Allen Clarke. 1863-1935. [Lancashire dialect novelist and socialist] Atticus William MacCall [pioneer anarchist, reviewer for The National Reformer] Aurelius, Marcus Walter Padley [author of Am I My Brother’s Keeper? Gollancz 1945; Labour MP and President of USDAW] Avis Alfred Sherman (before he became a close advisor to Margaret Thatcher, he had been in theCP in the 1940s, and used this name to write on Jewish issues) Barclay, P J John Archer (Trotskyist civil servant) Baron, Alexander Alec Bernstein [novelist] Barrett, George George Ballard [anarchist] Barrister, A Mavis Hill [Justice in England, LBC, 1938] Thurso, Berwick Morris Blythman [Scottish radical poet, singer-songwriter] B V James Thomson [Radical poet and reviewer] Bell, Lily Mrs Bream Pearce [in Keir Hardie’sLabour Leader] Bennet or Bennett Goldfarb [ECCI rep. to GB & Ireland; Head of Anglo-American Secretariat, C.I.; married Rose Cohen, CPGB. Both shot in 1937] Aka Lipec, Petrovsky, Breguer, Humboldt Berwick, -

Class Cohesion and Trade-Union Internationalism: Fred Bramley, the British TUC, and the Anglo-Russian Advisory Council

IRSH 58 (2013), pp. 429–461 doi:10.1017/S0020859013000175 r 2013 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Class Cohesion and Trade-Union Internationalism: Fred Bramley, the British TUC, and the Anglo-Russian Advisory Council K EVIN M ORGAN School of Social Sciences, University of Manchester Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: A prevailing image of the British trade-union movement is that it was insular and slow-moving. The Anglo-Russian Advisory Council of the mid-1920s is an episode apparently difficult to reconcile with this view. In the absence to date of any fully adequate explanation of its gestation, this article approaches the issue biographically, through the TUC’s first full-time secretary, Fred Bramley (1874–1925). Themes emerging strongly from Bramley’s longer history as a labour activist are, first, a pronouncedly latitudinarian conception of the Labour movement and, second, a forthright labour internationalism deeply rooted in Bramley’s trade- union experience. In combining these commitments in the form of an inclusive trade-union internationalism, Bramley in 1924–1925 had the indispensable support of the TUC chairman, A.A. Purcell who, like him, was a former organizer in the small but militantly internationalist Furnishing Trades’ Association. With Bramley’s early death and Purcell’s marginalization, the Anglo-Russian Committee was to remain a largely anomalous episode in the interwar history of the TUC. For historians of the international labour movement, Fred Bramley’s name registers, if at all, in one connection alone. In 1924–1925 it was with Bramley as its General Secretary that the British Trades Union Congress (TUC) entered into the close association with its Soviet counterpart that, until its break-up in 1927, was to be formalized in the Anglo-Russian Advisory Council (or Anglo-Russian Committee). -

Joint Industrial Councils in Great Britain: Reports of Committee On

U. S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS ROYAL MEEKER, Commissioner BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES\ (M OCC BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS/ * # * ( IlO . ZDD LABOR AS AFFECTED BY THE WAR SERIES JOINT INDUSTRIAL COUNCILS IN GREAT BRITAIN REPORTS OF COMMITTEE ON RELATIONS BETWEEN EMPLOYERS AND EMPLOYED, AND OTHER OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS JULY, 1919 W ASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1919 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis CONTENTS. Page. Introduction and summary............................................................................... 5-15 Summary of publications reproduced in this bulletin................................. 7-10 Progress of organization of joint industrial councils................................... 10-14 Whitley plan in industrial establishments controlled by Government departments..................................................................................... 12-14 Report on Whitley councils by Department of Labor commission of employers............................................................................................... 14,15 Reports of committee on relations between employers and employed............... 16-44 Interim report on joint standing industrial councils.................................. 16-23 Appendix............................................................................................. 22, 23 Second report on joint standing industrial councils....................................24-31 -

Socialist Sunday Schools in Britain, 1892–1939

F. REID SOCIALIST SUNDAY SCHOOLS IN BRITAIN, 1892-1939 Recent interest in the social conditions which underlay the emer- gence in Britain of independent labour politics in the last decade of the nineteenth century has thrown a good deal of light on the Labour Church movement.1 Dr. E. J. Hobsbawm, in a characteristically stimu- lating chapter of his Primitive Rebels, set the Labour Churches within the context of the "labour sects" which he isolates as a phenomenon of nineteenth century Britain and defines as "proletarian organisations and aspirations of a sort expressed through traditional religious ideology".2 The concentration of academic attention on the Labour Church has given rise to the mention of a little known phenomenon of the British working-class movement, Socialist Sunday Schools3 which, it is usually suggested, were little more than a fringe activity of the Labour Churches. It is the object of this paper to give some account of the history of Socialist Sunday Schools in Britain until 1939 and to suggest that they too constitute a "labour sect" cognate with the Labour Church but organisationally and geographically distinct from it and therefore representing an extension of the working-class sectarian tradition beyond the limits of the nineteenth century within which Hobsbawn seems to confine it.4 In the 1890s the seeds laid in the previous decade by the propaganda of the Socialist Societies5 and the revelations of the social investigators 1 The most comprehensive survey of the Labour Church movement in Britain is to be found in an unpublished Ph. D. thesis by D. -

''Little Soldiers'' for Socialism: Childhood and Socialist Politics In

IRSH 58 (2013), pp. 71–96 doi:10.1017/S0020859012000806 r 2013 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis ‘‘Little Soldiers’’ for Socialism: Childhood and Socialist Politics in the British Socialist Sunday School Movement* J ESSICA G ERRARD Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, 234 Queensberry Street, Parkville, 3010 VIC, Australia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper examines the ways in which turn-of-the-century British socialists enacted socialism for children through the British Socialist Sunday School movement. It focuses in particular on the movement’s emergence in the 1890s and the first three decades of operation. Situated amidst a growing international field of comparable socialist children’s initiatives, socialist Sunday schools attempted to connect their local activity of children’s education to the broader politics of international socialism. In this discussion I explore the attempt to make this con- nection, including the endeavour to transcend party differences in the creation of a non-partisan international children’s socialist movement, the cooption of traditional Sunday school rituals, and the resolve to make socialist childhood cultures was the responsibility of both men and women. Defending their existence against criticism from conservative campaigners, the state, and sections of the left, socialist Sunday schools mobilized a complex and contested culture of socialist childhood. INTRODUCTION The British Socialist Sunday School movement (SSS) first appeared within the sanguine temper of turn-of-the-century socialist politics. Offering a particularly British interpretation of a growing international interest in children’s socialism, the SSS movement attempted a non-partisan approach, bringing together socialists and radicals of various political * This paper draws on research that would not have been possible without the support of the Overseas Research Scholarship and Cambridge Commonwealth Trusts, Poynton Cambridge Australia Scholarship.