OUR HISTORY PAMPHLET 71 PRICE 40P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheet1 Page 1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen

Sheet1 Express & Star (West Midlands) 113,174 Manchester Evening News 90,973 Liverpool Echo 85,463 Aberdeen - Press & Journal 71,044 Dundee Courier & Advertiser 61,981 Norwich - Eastern Daily Press 59,490 Belfast Telegraph 59,319 Shropshire Star 55,606 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Evening Chronicle 52,486 Glasgow - Evening Times 52,400 Leicester Mercury 51,150 The Sentinel 50,792 Aberdeen - Evening Express 47,849 Birmingham Mail 47,217 Irish News - Morning 43,647 Hull Daily Mail 43,523 Portsmouth - News & Sports Mail 41,442 Darlington - The Northern Echo 41,181 Teesside - Evening Gazette 40,546 South Wales Evening Post 40,149 Edinburgh - Evening News 39,947 Leeds - Yorkshire Post 39,698 Bristol Evening Post 38,344 Sheffield Star & Green 'Un 37,255 Leeds - Yorkshire Evening Post 36,512 Nottingham Post 35,361 Coventry Telegraph 34,359 Sunderland Echo & Football Echo 32,771 Cardiff - South Wales Echo - Evening 32,754 Derby Telegraph 32,356 Southampton - Southern Daily Echo 31,964 Daily Post (Wales) 31,802 Plymouth - Western Morning News 31,058 Southend - Basildon - Castle Point - Echo 30,108 Ipswich - East Anglian Daily Times 29,932 Plymouth - The Herald 29,709 Bristol - Western Daily Press 28,322 Wales - The Western Mail - Morning 26,931 Bournemouth - The Daily Echo 26,818 Bradford - Telegraph & Argus 26,766 Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Journal 26,280 York - The Press 25,989 Grimsby Telegraph 25,974 The Argus Brighton 24,949 Dundee Evening Telegraph 23,631 Ulster - News Letter 23,492 South Wales Argus - Evening 23,332 Lancashire Telegraph - Blackburn 23,260 -

Pressreader Newspaper Titles

PRESSREADER: UK & Irish newspaper titles www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader NATIONAL NEWSPAPERS SCOTTISH NEWSPAPERS ENGLISH NEWSPAPERS inc… Daily Express (& Sunday Express) Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser Accrington Observer Daily Mail (& Mail on Sunday) Argyllshire Advertiser Aldershot News and Mail Daily Mirror (& Sunday Mirror) Ayrshire Post Birmingham Mail Daily Star (& Daily Star on Sunday) Blairgowrie Advertiser Bath Chronicles Daily Telegraph (& Sunday Telegraph) Campbelltown Courier Blackpool Gazette First News Dumfries & Galloway Standard Bristol Post iNewspaper East Kilbride News Crewe Chronicle Jewish Chronicle Edinburgh Evening News Evening Express Mann Jitt Weekly Galloway News Evening Telegraph Sunday Mail Hamilton Advertiser Evening Times Online Sunday People Paisley Daily Express Gloucestershire Echo Sunday Sun Perthshire Advertiser Halifax Courier The Guardian Rutherglen Reformer Huddersfield Daily Examiner The Independent (& Ind. on Sunday) Scotland on Sunday Kent Messenger Maidstone The Metro Scottish Daily Mail Kentish Express Ashford & District The Observer Scottish Daily Record Kentish Gazette Canterbury & Dist. IRISH & WELSH NEWSPAPERS inc.. Scottish Mail on Sunday Lancashire Evening Post London Bangor Mail Stirling Observer Liverpool Echo Belfast Telegraph Strathearn Herald Evening Standard Caernarfon Herald The Arran Banner Macclesfield Express Drogheda Independent The Courier & Advertiser (Angus & Mearns; Dundee; Northants Evening Telegraph Enniscorthy Guardian Perthshire; Fife editions) Ormskirk Advertiser Fingal -

Trinity Mirror…………….………………………………………………...………………………………

Annual Statement to the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO)1 For the period 1 January to 31 December 2017 1Pursuant to Regulation 43 and Annex A of the IPSO Regulations (The Regulations: https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/1240/regulations.pdf) and Clause 3.3.7 of the Scheme Membership Agreement (SMA: https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/1292/ipso-scheme-membership-agreem ent-2016-for-website.pdf) Contents 1. Foreword… ……………………………………………………………………...…………………………... 2 2. Overview… …………………………………………………..…………………...………………………….. 2 3. Responsible Person ……………………………………………………...……………………………... 2 4. Trinity Mirror…………….………………………………………………...……………………………….. 3 4.1 Editorial Standards……………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 4.2 Complaints Handling Process …………………………………....……………………………….. 6 4.3 Training Process…………………………………………....……………...…………………………….. 9 4.4 Trinity Mirror’s Record On Compliance……………………...………………………….…….. 10 5. Schedule ………………………………………………………………………...…...………………………. 16 1 1. Foreword The reporting period covers 1 January to 31 December 2017 (“the Relevant Period”). 2. Overview Trinity Mirror PLC is one of the largest multimedia publishers in the UK. It was formed in 1999 by the merger of Trinity PLC and Mirror Group PLC. In November 2015, Trinity Mirror acquired Local World Ltd, thus becoming the largest regional newspaper publisher in the country. Local World was incorporated on 7 January 2013 following the merger between Northcliffe Media and Iliffe News and Media. From 1 January 2016, Local World was brought in to Trinity Mirror’s centralised system of handling complaints. Furthermore, Editorial and Training Policies are now shared. Many of the processes, policies and protocols did not change in the Relevant Period, therefore much of this report is a repeat of those matters set out in the 2014, 2015 and 2016 reports. 2.1 Publications & Editorial Content During the Relevant Period, Trinity Mirr or published 5 National Newspapers, 207 Regional Newspapers (with associated magazines, apps and supplements as applicable) and 75 Websites. -

Planning Application: Report of Handling

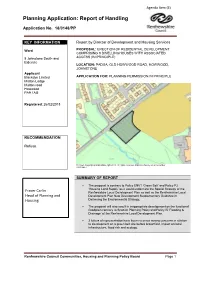

Agenda Item (E) Planning Application: Report of Handling Application No. 18/0148/PP KEY INFORMATION Report by Director of Development and Housing Services Ward PROPOSAL: ERECTION OF RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT COMPRISING 9 DWELLINGHOUSES WITH ASSOCIATED 8 Johnstone South and ACCESS (IN PRINCIPLE) Elderslie LOCATION: PADUA, OLD HOWWOOD ROAD, HOWWOOD, JOHNSTONE Applicant Blackdye Limited APPLICATION FOR: PLANNING PERMISSION IN PRINCIPLE Midton Lodge Midton road Howwood PA9 1AG Registered: 26/02/2018 RECOMMENDATION Refuse. © Crown Copyright and database right 2013. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100023417. SUMMARY OF REPORT • The proposal is contrary to Policy ENV1 ‘Green Belt’ and Policy P2 ‘Housing Land Supply’ as it would undermine the Spatial Strategy of the Fraser Carlin Renfrewshire Local Development Plan as well as the Renfrewshire Local Head of Planning and Development Plan New Development Supplementary Guidance in Delivering the Environmental Strategy. Housing • The proposal will also result in inappropriate development on the functional floodplain contrary to Scottish Planning Policy and Policy I5 ‘Flooding & Drainage’ of the Renfrewshire Local Development Plan. • 3 letters of representation have been received raising concerns in relation to development on a green belt site before brownfield, impact on local infrastructure, flood risk and ecology. Renfrewshire Council Communities, Housing and Planning Policy Board Page 1 RENFREWSHIRE COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING SERVICES REPORT OF HANDLING FOR APPLICATION 18/0148/PP APPLICANT: Blackdye Limited SITE ADDRESS: Padua, Old Howwood Road, Howwood, Johnstone, PA9 1AF PROPOSAL: Erection of residential development comprising 9 dwellinghouses with associated access (in principle). APPLICATION FOR: Planning Permission in Principle NUMBER OF Three letters of representation have been received. -

Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers

ID Heading Subject Organisation Person Industry Country Date Location 74 JIM GARDNER (null) AMALGAMATED UNION OF FOUNDRY WORKERS JIM GARDNER (null) (null) 1954-1955 1/074 303 TRADE UNIONS TRADE UNIONS TRADES UNION CONGRESS (null) (null) (null) 1958-1959 5/303 360 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS NON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS (null) (null) (null) 1942-1966 7/360 361 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS NOW ASSOCIATIONON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS N(null) (null) (null) 1967 TO 7/361 362 ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS CONFERENCES NONON MANUAL WORKERS ASSOCIATION OF SUPERVISORY STAFFS EXECUTIVES AND TECHNICIANS N(null) (null) (null) 1955-1966 7/362 363 ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS IN TECHNICAL INSTITUTIONS APPRENTICES ASSOCIATION OF TEACHERS IN TECHNICAL INSTITUTIONS (null) EDUCATION (null) 1964 7/363 364 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1929-1935 7/364 365 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1935-1962 7/365 366 BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH ACTORS EQUITY ASSOCIATION (null) ENTERTAINMENT (null) 1963-1970 7/366 367 BRITISH AIR LINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION (null) BRITISH AIR LINE PILOTS ASSOCIATION (null) TRANSPORT CIVIL AVIATION (null) 1969-1970 7/367 368 CHEMICAL WORKERS UNION CONFERENCES INCOMES POLICY RADIATION HAZARD -

St Mirren FC Stream

1 / 4 Live St Mirren FC Online | St Mirren FC Stream Jun 5, 2020 — Free live streaming will be available for season ticket holders if the ... ticket holders will be able to watch all home games online at no extra cost if the ... of action at St Mirren Park next season is by purchasing a season ticket.. Watch the Scottish Premiership event: Dundee FC - St. Mirren live on Eurosport. Scores, stats and comments in real time.. FotMob is the essential app for matchday. Get live scores, fixtures, tables, match stats, and personalised news from over 200 football leagues around the world.. ... to compare statistics for both teams. St Mirren FC 1-1 Motherwell FC FT. ... Motherwell vs St Mirren live streaming: Match details. Inclusive of half-time, full-time .... St Mirren season ticket holders will be able to watch the match for free on ... 2016-17 St Mirren Football fixtures, results scores, news and pictures on Sports ... Streams Below you can find where you can watch live St Mirren U21 online in UK.. Jun 21, 2021 · Xem tường thuật trực tiếp trận Goiás vs Avai FC, 05:00 - 23/06 trên kênh Mitom TV. ... Fluminense vs Goiás Predictions & H2H Goiás live score (and video online live stream*), team roster with ... Goias EC GO vs Coritiba FC PR Live Streaming 09.09.2020 . ... Dumbarton FC - St. Mirren 10/07/2021 16:00.. Get Live Football Scores and Real-Time Football Results with LiveScore! We cover all Countries ... 09:00Lincoln Red Imps FC? - ?CS Fola Esch ... St. Johnstone.. Bet on Football at Sky Bet. -

10 Berl Avenue, Houston.Indd

10 Berl Avenue HOUSTON, JOHNSTONE, RENFREWSHIRE, PA6 7JJ 0141 404 5474 Houston Johnstone Renfrewshire PA6 7JJ LOCATION // Houston’s historic village centre is a designated conservation area and is home to village pubs, restaurants, a micro brewery, small shops and the village’s Post Office. Nearby schools include two excellent primary schools in Houston, with Gryffe High School providing highly rated, secondary education. Independent schooling is available at St Columba’s School in nearby Kilmacolm, consistently one of Scotland’s most successful schools in examination league table results. Houston is well placed for commuting with excellent road access to Inverclyde, the Ayrshire coast, local marinas, equestrian facilities, fishing and country parks, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, Glasgow Airport, the M8 and Glasgow city centre. There is a railway station at Johnstone and Bishopton with ample car parking and regular and frequent services. 10 Berl Avenue PROPERTY // McEwan Fraser Legal are delighted to introduce to the market this fantastic four bedroom detached villa which offers fantastic and flexible accommodation formed over two levels, with a beautiful outlook. The property has been designed to maximise the natural available light to create a modern ambience, with interesting views to both the front and rear. Once inside, discerning purchasers will be greeted with a first class specification. A welcoming hallway sets the tone for the rest of the property. An impressive lounge is flooded with natural light from the large window to the front aspect whilst offering a pleasant outlook. The breakfasting kitchen has a modern range of floor and wall mounted units with a striking worktop, creating a fashionable and efficient workspace. -

Summer Clubs

Summer Club dates WEEK 1 Monday 2 July–Saturday 7 July FREE WEEK 2 Monday 9 July–Saturday 14 July WEEK 3 Monday 16 July–Saturday 21 July WEEK 4 Monday 23 July–Saturday 28 July WEEK 5 Monday 30 July–Saturday 4 August WEEK 6 Monday 6 August–Saturday 11 August We’re working hard * PLEASE NOTE A free healthy meal will only be provided during to improve our streets afternoon sessions but we need your For more details and up to date information help too! go to www.renfrewshire.gov.uk/streetstuff @SMFCStreetStuff @streetstuffdnc Community organisations, clubs, churches, schools and individuals - we need you to lead the charge and organise Our you can contact Stephen Gallacher, Street Stuff a community clean up. We will provide you with all the equipment and advice you need for a successful event. Manager or Emma Phelan Street Stuff Dance Coordinator at: Stephen Gallacher Emma Phelan SUMMER CLUBS Street Stuff Manager Street Stuff Dance Co-ordinator 07557 281581 07702 864492 2 JULY–11 AUGUST [email protected] [email protected] Call 0300 300 1375, email Free healthy meal provided* [email protected] or visit www.renfrewshire.gov.uk/teamuptocleanup Timetable A free healthy meal provided during afternoon sessions only Monday July: 2, 9,16, 23, 30 August: 6 Thursday July: 5,12, 19, 26 August: 2, 9 Afternoon 1.30–4.30pm Football Dance Youth Bus Afternoon 1–5pm Football Dance Youth Bus St James Primary—Renfrew Gleniffer High Astro Sign Up Sheet McMaster Centre—Johnstone St Mirren Football Club 1–5pm For ages 8 and over -

Johnstone SW Charette

Edinburgh Research Explorer Johnstone South West Design Charrette: Evaluation Report Citation for published version: Forsyth, L 2011, Johnstone South West Design Charrette: Evaluation Report. Scottish Government, Edinburgh. <http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Built- Environment/AandP/Projects/SSCI/Mainstreaming/Johnstonerept> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publisher Rights Statement: © Forsyth, L. (2011). Johnstone South West Design Charrette: Evaluation Report. Edinburgh: Scottish Government. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Transforming Johnstone South West Masterplan Framework February 2012 1 2 Proposed Illustrative Masterplan - Johnstone South West Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2012. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey licence number 100023417. 3 Transforming Johnstone South West: The 2021 Vision The Best of Both - where countryside and town meet This Executive Summary highlights the main Johnstone South West is renowned as a outputs from the Johnstone South West good place to live. -

Bridge of Weir Houston Johnstone for More Information Visit Spt.Co.Uk

Ref. W065E/07/19 Route Map Service 2/2A Whilst every effort will be made to adhere to the scheduled times, the Partnership disclaims any liability in respect of loss or inconvenience arising from any failure to operate journeys as Bus Timetable published, changes in timings or printing errors. From 14 July 2019 2/2A Bridge of Weir Houston Johnstone For more information visit spt.co.uk. Alternatively, for all public transport enquiries, call: This service is operated by McGill’s Bus This service is operated by Service Ltd on behalf of Strathclyde McGill’s Bus Service Ltd on Partnership for Transport. If you have any behalf of SPT. comments or suggestions about the service(s) provided please contact: SPT McGill’s Bus Service Ltd Bus Operations 99 Earnhill Road 131 St. Vincent St Larkfield Industrial Est. Glasgow G2 5JF Greenock PA16 0EQ t 0345 271 2405 t 08000 515 651 0141 333 3690 e [email protected] e [email protected] Please note – Calls to 0845 271 2405 will be charged at 2p per min (inc. VAT) plus your Telecoms Providers Access Charge Service 2/2A Bridge of Weir – Houston – Johnstone Operated by McGill’s Bus Service Ltd on behalf of SPT Service 2 from Johnstone Station via High Street, Barrochan Road, Bridge of Weir Road, Bridge of Weir Main Street Houston Road, Old Bridge of Weir Road, Houston Road, Bridge of Weir Road, Houston Road, Magnus Road, Fulton Drive, Barrochar Road, Darluith Road, Clippens Road, Erskinefauld Road, Greenfarm Road, Moss Road, Bridge Street, A761, A737, Barrochan Road, High Street, to Johnstone Station. -

Muirdykes Supply Area Water Main Rehabilitation Works

GEORGE LESLIE LTD CIVIL ENGINEERING CONTRACTORS MUIRDYKES SUPPLY AREA WATER MAIN REHABILITATION WORKS This project in the Muirdykes RSZ covered South Paisley, Johnstone, Kilbarchan, Linwood and Howwood and comprised the Design & Build of 177km of water main rehab and upgrading work on the public water trunk and distribution supply network. The objective was to satisfy the DW5 criteria to reduce the high levels of manganese which had resulted in severe discolouration in the water supply. Detailed design work included: analysis of historical records, street-by-street surveys, extensive trial-hole site investigation and non-destructive testing of the existing pipelines, from which the most cost-effective intervention solution was developed in compliance with the ‘DW5’ methodology. The design was also subject to regular review and governance approvals by client stakeholders before final adoption. Extensive stakeholder consultation and approvals were necessary prior to commencing on site, to ensure traffic restrictions and road closures could be effected and private land entry agreed. Close co-operation with Scottish Water’s Customer Service Delivery teams ensured that planned interruptions to supply were minimised and close co-operation with SW operations teams enabled reconfiguring of the network to maintain supply to customers wherever possible. Across the programme, some 25km of pipeline was relined, with the remainder subject to a variety of intervention techniques ranging from simple swabbing and flushing, to the more intrusive slip-lining and pipe-bursting. On unavoidable instances, complete pipeline replacement was undertaken. Through innovative design and efficient delivery techniques, out-turn savings of £500,000 were realised on this £3m programme of work. -

Newspapers (Online) the Online Newspapers Are Available in “Edzter”

Newspapers (Online) The Online Newspapers are available in “Edzter”. Follow the steps to activate “edzter” Steps to activate EDZTER 1. Download the APP for IOS or Click www.edzter.com 2. Click - CONTINUE WITH EMAIL ADDRESS 3. Enter University email ID and submit; an OTP will be generated. 4. Check your mail inbox for the OTP. 5. Enter the OTP; enter your NAME and Click Submit 6. Access EDZTER - Magazines and Newspapers at your convenience. Newspapers Aadab Hyderabad Dainik Bharat Rashtramat Jansatta Delhi Prabhat Khabar Kolkata The Chester Chronicle The Times of India Aaj Samaaj Dainik Bhaskar Jabalpur Jansatta Kolkata Punjab Kesari Chandigarh The Chronicle The Weekly Packet Agro Spectrum Disha daily Jansatta Lucknow Retford Times The Cornishman Udayavani (Manipal) Amruth Godavari Essex Chronicle Kalakamudi Kollam Rising Indore The Daily Guardian Vaartha Andhra Pradesh Art Observer Evening Standard Kalakaumudi Trivandrum Rokthok Lekhani Newspaper The Free Press Journal Vaartha Hyderabad Ashbourne News Financial Express Kashmir Observer Royal Sutton Coldfield The Gazette Vartha Bharati (Mangalore) telegraph Observer Ayrshire Post First India Ahmedabad Kids Herald Sakshi Hyderabad The Guardian Vijayavani (Belgavi) Bath Chronicle First India Jaipur Kidz Herald samagya The Guardian Weekly Vijayavani (Bengaluru) Big News First India Lucknow Leicester Mercury Sanjeevni Today The Herald Vijayavani (Chitradurga) Birmingham Mail Folkestone Herald Lincoln Shire Echo Scottish Daily Express The Huddersfield Daily Vijayavani (Gangavathi) Examiner