Hani-Rabbat As the Semitic Name of Mitanni*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-7-2014 Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power in the Bronze Age: A Characterization Study of Ceramics from Bronze Age Sites in Kuwait Hasan Ashkanani University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ashkanani, Hasan, "Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power in the Bronze Age: A Characterization Study of Ceramics from Bronze Age Sites in Kuwait" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4980 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power in the Bronze Age: A Characterization Study of Ceramics from Bronze Age Sites in Kuwait by Hasan J. Ashkanani A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. Thomas J. Pluckhahn, Ph.D. E. Christian Wells, Ph.D. Jonathan M. Kenoyer, Ph.D. Jeffrey Ryan, Ph.D. Date of Approval April 7, 2014 Keywords: Failaka Island, chemical analysis, pXRF, petrographic thin section, Arabian Gulf Copyright © 2014, Hasan J. Ashkanani DEDICATION I dedicate my dissertation work to the awaited savior, Imam Mohammad Ibn Al-Hasan, who appreciates knowledge and rejects all forms of ignorance. -

Nochmals Zur Geschichte Und Lage Der Hethitischen Stadt Ankuwa

STUDI MICENEI ED EGEO-ANATOLICI FASCICOLO XXIV IN MEMORIA DI PIERO MERIGGI (1899-1982) ff ROMA, EDIZIONI DELL'ATENEO 1984 INDICE DEL FASCICOLO XXIV Ricordo di Piero Meriggi Pdg> 3 Ncar Eastern Trade and the Emergencc of Interaction with Grete in the Third Millennium B.C., by HORST KLENGEL » 7 Nilabsinu und der altorientalische Name des Teil Brak, von KARLHEINZ KESSLER » 21 Zu den hurritischen Personennamen aus Kär-Tukulti-Ninurta, von HELMUT FREYDANK und MIRJO SALVINI » 33 Nasalization im Anatolischen, von ONOFRIO CARRUBA » 57 Studien über das hethitische Kriegswesen II: Verba delendi har- ninkr/harganu- «vernichten, zugrunde richten», von AHMET UNAL » 71 Nochmals zur Geschichte und Lage der hethitischen Stadt Ankuwa, von AHMET ÜNAL » 87 II ruolo delle «truppe» UKU.U§ nell'organizzazione militare ittita, di SUSANNA Rosi » 109 II LUALAN.ZÜ come «mimo» e come «attore» nei testi ittiti, di STEFANO DE MARTINO » 131 Ittito:L^PFIN^^SAR)=§U.KI§SAR((ortica (?))>, di MIRELLA VITO ... » 149 Scribi hurriti a Bogazköy: una verifica prosopografica, di LORENZA M. MASCHERONI » 151 Die hethitisch-hurritischen Rituale des (h)isuwa-F estes, von MIRJO SALVINI und ILSE WEGNER » 175 Eine Anrufung an den Gott Tessup von Halab in hurritischer Sprache, von H.-J. THIEL! und ILSE WEGNER » 187 Die Inschrift auf der Statue der Tatu-Hepa und die hurritischen deikti• schen Pronomina, von GERNOT WILHELM » 215 Hurritisch nari(ya) «fünf», von GERNOT WILHELM » 223 The Outline of Anatolian Onomastics, by ARAM V. KHOSSIAN » 225 Le pays Istikuniu d'une inscription cuneiforme -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Hanigalbat and the Land Hani

Arnhem (nl) 2015 – 3 Anatolia in the bronze age. © Joost Blasweiler student Leiden University - [email protected] Hanigal9bat and the land Hana. From the annals of Hattusili I we know that in his 3rd year the Hurrian enemy attacked his kingdom. Thanks to the text of Hattusili I (“ruler of Kussara and (who) reign the city of Hattusa”) we can be certain that c. 60 years after the abandonment of the city of Kanesh, Hurrian armies extensively entered the kingdom of Hatti. Remarkable is that Hattusili mentioned that it was not a king or a kingdom who had attacked, but had used an expression “the Hurrian enemy”. Which might point that formerly attacks, raids or wars with Hurrians armies were known by Hattusili king of Kussara. And therefore the threatening expression had arisen in Hittite: “the Hurrian enemy”. Translation of Gary Beckman 2008, The Ancient Near East, editor Mark W. Chavalas, 220. The cuneiform texts of the annal are bilingual: Babylonian and Nesili (Hittite). Note: 16. Babylonian text: ‘the enemy from Ḫanikalbat entered my land’. The Babylonian text of the bilingual is more specific: “the enemy of Ḫanigal9 bat”. Therefore the scholar N.B. Jankowska1 thought that apparently the Hurrian kingdom Hanigalbat had existed probably from an earlier date before the reign of Hattusili i.e. before c. 1650 BC. Normally with the term Mittani one is pointing to the mighty Hurrian kingdom of the 15th century BC 2. Ignace J. Gelb reported 3 on “the dragomans of the Habigalbatian soldiers/workers” in an Old Babylonian tablet of Amisaduqa, who was a contemporary with Hattusili I. -

"Ancient Terqa and Its Temple of Ninkarrak: the Excavations of The

ANCIENT TERQA AND ITS TEMPLE OF NINKARRAK: THE EXCAVATIONS OF THE FIFTH AND SIXTH SEASONS Renata M. Liggett Assistant Director, Joint Expedition to Terqa Doctoral Student, Near Eastern Languages & Cultures-UCLA Introduction The historical record of an ancient region can be traced archaeologically by artifactual, archival, linguistic, artistic, architectural and ceramic records. In the developments of the past few years at, for instance, Tell Mardikh in northern Syria, a single resource, such as a grammatical element or mention of a fdreign ruler, can provide the basis or a clue for a new interpretation of the material. The excavations at Terqa are intended to incorporate all manner of data into a reconstruction of the historical record of the Mid-Euphrates region. This article provides a brief overview of the recent archaeological discoveries, which, applied to the many facets of research surrounding the ancient city of Terqa and its environs, will produce a solid understanding of a particular region at various crucial times in the history of ancient Syria. Ongoing contributions to this goal include philological research, particularly involving onomastics and applied computer technology, sphragistic (cylinder seal) analysis by an encoded com- puter data base, particularly of the Old Babylonian and Khana periods, chronological assessment of ceramic types, partly by atomic absorption sourcing techniques, and a continuing development of an advanced methodology, especially stratigraphic analysis, again applying computer technology. Associated projects also include innovations in archaeological equipment, tested on-site at Terqa, such as an instrument for overhead aerial photography. Most recently, an important orgspic geochemical study conducted on ancient samples of asphalt from Terqa /~aturq,Vol. -

Sumerian Lexicon, Version 3.0 1 A

Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0 by John A. Halloran The following lexicon contains 1,255 Sumerian logogram words and 2,511 Sumerian compound words. A logogram is a reading of a cuneiform sign which represents a word in the spoken language. Sumerian scribes invented the practice of writing in cuneiform on clay tablets sometime around 3400 B.C. in the Uruk/Warka region of southern Iraq. The language that they spoke, Sumerian, is known to us through a large body of texts and through bilingual cuneiform dictionaries of Sumerian and Akkadian, the language of their Semitic successors, to which Sumerian is not related. These bilingual dictionaries date from the Old Babylonian period (1800-1600 B.C.), by which time Sumerian had ceased to be spoken, except by the scribes. The earliest and most important words in Sumerian had their own cuneiform signs, whose origins were pictographic, making an initial repertoire of about a thousand signs or logograms. Beyond these words, two-thirds of this lexicon now consists of words that are transparent compounds of separate logogram words. I have greatly expanded the section containing compounds in this version, but I know that many more compound words could be added. Many cuneiform signs can be pronounced in more than one way and often two or more signs share the same pronunciation, in which case it is necessary to indicate in the transliteration which cuneiform sign is meant; Assyriologists have developed a system whereby the second homophone is marked by an acute accent (´), the third homophone by a grave accent (`), and the remainder by subscript numerals. -

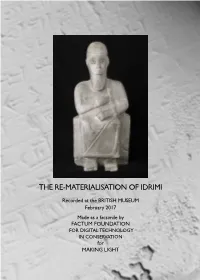

The Re-Materialisation of Idrimi

THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI Recorded at the BRITISH MUSEUM February 2017 Made as a facsimile by FACTUM FOUNDATION FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CONSERVATION for MAKING LIGHT THE RE-MATERIALISATION OF IDRIMI SEPTEMBER 2017 The Statue of Idrimi photographed during the recording session at the British Museum in February 2017 2 THE STATUE OF IDRIMI The statue of Idrimi, carved in magnesite with inlaid glass eyes, too delicate and rare to ever travel, has been kept in a glass case at the British Museum since its discovery by the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley in 1939. It was ex- cavated in what is now part of Turkey at Tell Atchana, the remains of the ancient Syrian city-state of Alalakh. From the autobiographical cuneiform inscription on the statue, we know that Idrimi was King of Alalakh in the 15th century BC. A son of the royal house of Aleppo, Idrimi fled his home as a youth with his family and after spending some years in Emar and then amongst the tribes in Canaan, became King of Alalakh. At the time of inscribing the statue, Idrimi had ruled Alalakh for thirty years. The inscription is considered one of the most interesting cuneiform texts ever found, both because of its autobiographical nature and because of the rarity of the script. It describes Idrimi’s early life and escape from Aleppo into the steppes, his accession to power, as well as the military and social achievements of his reign. It places a curse on any person who moves the statue, erases or in any way alters the words, but the inscription ends by commending the scribe to the gods and with a blessing to those who would look at the statue and read the words: “I was king for 30 years. -

The Spatial Dimensions of Early Mesopotamian Urbanism: the Tell Brak Suburban Survey, 2003-2006

The Spatial Dimensions of Early Mesopotamian Urbanism: The Tell Brak Suburban Survey, 2003-2006 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ur, Jason, Philip Karsgaard, and Joan Oates. 2011. The Spatial Dimensions of Early Mesopotamian Urbanism: The Tell Brak Suburban Survey, 2003-2006. Iraq 73: 1-19. Published Version http://www.britac.ac.uk/INSTITUTES/IRAQ/journal.htm Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:5366597 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA VOLUME LXXIII • 2011 CONTENTS Editorial iii Obituaries: Dr Donny George Youkhanna, Mrs Rachel Maxwell-Hyslop v Jason Ur, Philip Karsgaard and Joan Oates: The spatial dimensions of early Mesopotamian urbanism: The Tell Brak suburban survey, 2003–2006 1 Carlo Colantoni and Jason Ur: The architecture and pottery of a late third-millennium residential quarter at Tell Hamoukar, north-eastern Syria 21 David Kertai: Kalæu’s palaces of war and peace: Palace architecture at Nimrud in the ninth century bc 71 Joshua Jeffers: Fifth-campaign reliefs in Sennacherib’s “Palace Without Rival” at Nineveh 87 M. P. Streck and N. Wasserman: Dialogues and riddles: Three Old Babylonian wisdom texts 117 Grégory Chambon and Eleanor Robson: Untouchable or unrepeatable? The upper end of -

The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms

McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee with contributions from Tom D. Dillehay, Li Min, Patricia A. McAnany, Ellen Morris, Timothy R. Pauketat, Cameron A. Petrie, Peter Robertshaw, Andrea Seri, Miriam T. Stark, Steven A. Wernke & Norman Yoffee Published by: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Downing Street Cambridge, UK CB2 3ER (0)(1223) 339327 [email protected] www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019 © 2019 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 (International) Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ISBN: 978-1-902937-88-5 Cover design by Dora Kemp and Ben Plumridge. Typesetting and layout by Ben Plumridge. Cover image: Ta Prohm temple, Angkor. Photo: Dr Charlotte Minh Ha Pham. Used by permission. Edited for the Institute by James Barrett (Series Editor). Contents Contributors vii Figures viii Tables ix Acknowledgements x Chapter 1 Introducing the Conference: There Are No Innocent Terms 1 Norman Yoffee Mapping the chapters 3 The challenges of fragility 6 Chapter 2 Fragility of Vulnerable Social Institutions in Andean States 9 Tom D. Dillehay & Steven A. Wernke Vulnerability and the fragile state -

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6 -

Ugaritic Seal Metamorphoses As a Reflection of the Hittite Administration and the Egyptian Influence in the Late Bronze Age in Western Syria

UGARITIC SEAL METAMORPHOSES AS A REFLECTION OF THE HITTITE ADMINISTRATION AND THE EGYPTIAN INFLUENCE IN THE LATE BRONZE AGE IN WESTERN SYRIA The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by B. R. KABATIAROVA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ART BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA June 2006 To my family and Őzge I certify that I have read this thesis and that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art. -------------------------------------------- Dr. Marie-Henriette Gates Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art. -------------------------------------------- Dr. Jacques Morin Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and that it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and History of Art. -------------------------------------------- Dr. Geoffrey Summers Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences ------------------------------------------- Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT UGARITIC SEAL METAMORPHOSES AS A REFLECTION OF THE HITTITE ADMINISTRATION AND THE EGYPTIAN INFLUENCE IN THE LATE BRONZE AGE IN WESTERN SYRIA Kabatiarova, B.R. M.A., Department of Archaeology and History of Art Supervisor: Doc. Dr. Marie-Henriette Gates June 2006 This study explores the ways in which Hittite political control of Northern Syria in the LBA influenced and modified Ugaritic glyptic and methods of sealing documents. -

Indo-Iranian Personal Names in Mitanni: a Source for Cultural Reconstruction DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/8

Onoma 54 Journal of the International Council of Onomastic Sciences ISSN: 0078-463X; e-ISSN: 1783-1644 Journal homepage: https://onomajournal.org/ Indo-Iranian personal names in Mitanni: A source for cultural reconstruction DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/8 Simone Gentile Università degli Studi di Roma Tre Dipartimento di Filosofia, Comunicazione e Spettacolo via Ostiense, 234˗236 00146 Roma (RM) Italy [email protected] To cite this article: Gentile, Simone. 2019. Indo-Iranian personal names in Mitanni: A source for cultural reconstruction. Onoma 54, 137–159. DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/8 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.34158/ONOMA.54/2019/8 © Onoma and the author. Indo-Iranian personal names in Mitanni: A source for cultural reconstruction Abstract: As is known, some Indo˗Aryan (or Iranian) proper names and glosses are attested in documents from Egypt, Northern Mesopotamia, and Syria, related to the ancient kingdom of Mitanni (2nd millennium BC). The discovery of these Aryan archaic forms in Hittite and Hurrian sources was of particular interest for comparative philology. Indeed, some names can be readily compared to Indo˗Iranian anthroponyms and theonyms: for instance, Aššuzzana can likely be related with OPers. Aspačanā ‘delighting in horses’, probably of Median origin; Indaratti ‘having Indra as his guest’ clearly recalls Indra, a theonym which occurs both in R̥ gveda and Avesta. This paper aims at investigating the relationship between Aryan personal names preserved in Near Eastern documents and the Indo˗Iranian cultural milieu. After a thorough collection of these names, their 138 SIMONE GENTILE morphological and semantic structures are analysed in depth and the most relevant results are showed here.