GAO-07-863 Climate Change: Agencies Should Develop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRIBUNE-EXAMINER Dillon, Montana Freshmen Arrival Opens Page 2 Tuesday, August 6,1974 Southwestern Montana Report 82Nd Year for Western

DAILY TRIBUNE-EXAMINER Dillon, Montana Freshmen arrival opens Page 2 Tuesday, August 6,1974 Southwestern Montana Report 82nd year for Western Freshman students arriving gymnasiums, all-weather arena, Sunday, Sept. 22, will mark the handball courts, offices and opening of autumn quarter at classrooms; the Lucy Carson Meetings Dillon Police Western Montana College and the Library and Administration Tuesday, August 6 Dillon unit’s 82nd year as a Building with its bookcenter Monday Dillon police officersmember of the Montana providing over 75,000 volumes, City Hi Lo THURSDAY, AUGUST 8 10,000 visual aids, and an ex Meetings Billings............................93 63 Drivers Licenses, 9-4 tests, 9-5 made five arrests for public University System. intoxication. ' Orientation for the first-year tensive selection of periodicals; VolunteerJFiremen, 8 p.m., Fire Hall. Belgrade ....................... 89 55 renewals, Courthouse. and the Faculty Office- \ An accident occurred at 8:06 collegians is scheduled Sept. 23 Broadus.......................... 89 M Elks Bingo Night, 8 p.m., Elks Classroom structure, a science B utte....................... 88 59 Lounge. p.m. when Don Burgess, driving with an 8:15 a.m. general a 1962 Ford station wagon, hit aassembly featuring introduction and mathematics center in Wednesday, August 7 Cut Bank ....................... 93 62 Beaverhead Sportsmen’s corporating 11 special-purpose Dillon............................... 90 53 Association, 7:30 p.m., Vigilantepole at Davis Conoco. He wasof staff members, departmental laboratories. Meetings _ Glasgow.......................... 93 60 Electric. cited for careless driving and counseling, and testing public intoxication. programs. Despite enrollment declines Dillon Nile Club, 1:30 p.m., Royal Inn. Great Falls..................... 97 64 which have afflicted state and Havre ...........................100 62 An accident was reported to General registration will be police officer South from Barrettconducted Sept. -

Alice Cooper 2011.Pdf

® • • • I ’ M - I N - T HE - MIDDLE-WIT HOUT ANT PLANS - I’M A BOY AND I’M-A MAN - I.’ M EIGHTEEN- - ® w Q < o ¡a 2 Ó z s * Tt > o ALICE M > z o g «< COOPER s [ BY BRAD T O L I N S K I ] y a n y standards, short years before, in 1967, Alice Cooper 1973 was an had been scorned as “the most hated exceptional year band” in Los Angeles. The group members for rock & roll. weirded out the locals by being the first Its twelve months hoys that weren’t transvestites to dress as saw the release girls, and their wildly dissonant, fuzzed- of such gems as out psychedelia sent even the most liberal Pink Floyd s The Dark Side of the Moon, hippies fleeing for the door. Any rational H H Led Zeppelin s Houses of the Holy, the human would have said they were 0 o W ho’s Quadrophenia, Stevie Wonders committing professional suicide, but z Innervisions, Elton Johns Goodbye Yellow the band members thought otherwise. Brick Road, and debuts from Lynyrd Who cared if a bunch o f Hollywood squares Skynyrd, Aerosmith, Queen, and the New thought they were gay? At least they Y ork D olls. were being noticed. But the most T H E BAND Every time they provocative and heard somebody audacious treasure G R A B B E D y e ll “faggot;” they of that banner year H EA D LIN ES AND swished more, and was Alice Coopers overnight they found £ o masterpiece, B illio n MADE WAVES fame as the group z w Dollar Babies, a it was hip to hate H m brilliant lampoon of American excess. -

No More Mr Nice Guy: the Inside Story of the Alice Cooper Group Online

vmBnJ (Read free) No More Mr Nice Guy: The Inside Story of the Alice Cooper Group Online [vmBnJ.ebook] No More Mr Nice Guy: The Inside Story of the Alice Cooper Group Pdf Free Michael Bruce, Billy James *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2573547 in Books 2017-03-06Original language:English 9.21 x .27 x 6.14l, #File Name: 1908728698126 pages | File size: 55.Mb Michael Bruce, Billy James : No More Mr Nice Guy: The Inside Story of the Alice Cooper Group before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised No More Mr Nice Guy: The Inside Story of the Alice Cooper Group: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. The other side of the coinBy B. WaringThis book is a definite must- have for the Alice Cooper completist. Although the editing is very poor, I could overlook that for the content and other- side-of-the-coin views from Michael Bruce, a big part of the Alice Cooper group as a song-writer and singer. He was instrumental in the creation of the group's biggest hits. There were obviously some bitter feelings among some of the other group members, as related to their lead singer's popularity in the media. I enjoyed reading this as an informational source and to get another opinion of what had transpired within the group's creation and demise.19 of 21 people found the following review helpful. This is the real Alice Cooper !By A CustomerThe Alice Cooper you see today is not the same Alice Cooper that roamed the earth from 1971-1973. -

From Straight to Bizarre Zappa, Beefheart, Alice Cooper and LA's

From Straight To Bizarre Zappa, Beefheart, Alice Cooper And LA's Lunatic Fringe Sexy Intellectual DVD This considered examination of the eccentric landscape of the infamous Bizarre/Straight catalogue makes for compleling viewing and with a running time of some two hours and 40 minutes the film gives its subject the screen time it so richly deserves. Created by Zappa and Mothers manager Herb Cohen in 1968 as a release outlet specialising in the weird, the wonderful and the strictly non mainstream following Zappa's clashes with his former label MGM over the old stumblig block of artistic control the extraordinary Bizarre/Straight story is infamous for having given the world such unforgettable cultural landmarks as An Evening With Wild Man Fischer and Trout Mask Replica. With Zappa operating as LA's resident king of the freaks from his Laurel Canyon hideaway, the documentary chronicles the labels groundbreaking appetite for assembling a notorious roster of misfits including The GTOs, Wild Man Fischer, Captain Beefheart & The Magic Band, Lenny Bruce, Lord Buckley, Tim Buckley, accappella gospel group The Persuasions and the labels greatest commercial success Alice Cooper via the input of interviewees including Pamela Des Barres, Kim Fowley, Bill Harkleroad, John French, Neal Smith, Dennis Dunaway, Jeff Simmons and an impressive array of vintage performance footage. While the Bizarre/Straight era represented a unique chapter in the annals of the late 60s and early 70s the thrust of the film's critical commentary is that if the entire Bizarre/Straight operation had only given the world Trout Mask Replica it would still have more than have achieved its goal. -

The Plasmatics' Brand of High-Energy Rock 'N' Roll May Only Be

Wendy O Williams - 10 Years of Revolutionary Rock and Roll - MVD Visuals - DVD Page 1 of 3 Home | | Archives | TAPSheet | C 01/03/07 Reviewed by - Matt Rowe The Plasmatics’ brand of high-energy Rock ‘n’ Roll may only be matched by a few bands even to this day. They came in on the punk wave in 1978 and gave 10 years of ferocious music along with the theatre to back it up that included blowing up of cars, chain-sawing, and more than a measure of flesh courtesy of one firebrand, Wendy O Williams. She flaunted the barriers that were in place although they were certainly challenged by other bands. But no one had the same measure of intensity that drove The Plasmatics to a greater height of rock insurrection, and it was all governed by the heat that boiled inside the girl that let no boundary contain her. MVD Visual releases a DVD that contains more than 3 hours of Wendy O Williams spotlight focused on the front of The Plasmatics, Wendy O Williams And The and her band. WoW was called The Queen of Punk, The High Priestess Plasmatics of Metal, The Dominatrix of the Decibels, and The Queen of Shock Rock, which, all by itself, was an appropriate name as she consistently found the nudge that would upset and shock in an increasing manner until the band outlived its shock appeal. This DVD shows all of the theatrics, sexuality, and nihilism that accompanied a Plasmatics show. With an ability to incite her audience, Wendy O Williams, who pushed the exposure of her nude flesh as close to the limit allowable in that period, used every angle to take rock to the next level (we’ve regressed since then). -

Alice Cooper: El Rei Del Shock Rock

It's only rock & roll | Pep Saña | Actualitzat el 30/08/2017 a les 12:56 Alice Cooper: El rei del Shock Rock Fill d'un predicador, Vincent Damon Furnier (nascut el 4 de febrer de 1948 a Detroit Michigan), degut a complicacions amb la seva salut durant l'adolescència, va haver de mudar-se amb la seva família a Phoenix, Arizona, on va aconseguir graduar-se en belles arts. Més endavant conegut com Alice Cooper, va ser un dels pioners en associar rock i espectacle als seus concerts, muntar petites històries teatrals a l'escenari mentre tocava la banda de rock i crear de si mateix un personatge sorgit del més sòrdid dels malsons. Amb maquillatges d'aspecte sinistre, inquietants lletres i concerts que incloïen execucions amb guillotina, cadires elèctriques o aparicions amb serps enormes (com la famosa boa constrictor), il?lustraven els continguts dels seus àlbums, molts dels quals explicaven una història, en la més pura línia de l'àlbum conceptual. Alice Cooper, seria el primer a desenvolupar amb més sofisticació les posades en escena respecte a altres músics influenciats per l'estètica glam teatral, com David Bowie o Peter Gabriel. Aquesta característica escènica influenciaria notablement a grups com KISS, Mötley Crüe o Twisted Sister entre d'altres. El seu show en escena el mostra tallant bebès amb una destral o presentant-se a president dels Estats Units. Alice Cooper també és famós per la seva carismàtica personalitat fora de l'escenari, estant escollit com l'artista de heavy metal més estimat, publicat per la famosa revista Rolling Stone. -

Bio-Alice Cooper

ALICE COOPER Alice Cooper pioneered a grandly theatrical brand of hard rock that was designed to shock. Drawing equally from horror movies, vaudeville, and garage rock, the group created a stage show that featured electric chairs, guillotines, fake blood and boa constrictors. He continues to tour regularly, performing shows worldwide with the dark and horror-themed theatrics that he’s best known for. With a schedule that includes six months each year on the road (pre-Covid), Alice Cooper brings his own brand of rock psycho-drama to fans both old and new, enjoying it as much as the audience does. Known as the architect of shock-rock, Cooper (in both the original Alice Cooper band and as a solo artist) has rattled the cages and undermined the authority of generations of guardians of the status quo, continuing to surprise fans and exude danger at every turn, like a great horror movie, even in an era where CNN can present real life shocking images. Cooper was born in Detroit Michigan, and moved to Phoenix with his family. The Alice Cooper band formed while they were all in high school in Phoenix, and was discovered in 1969 by Frank Zappa in Los Angeles, where he signed them to his record label. Their collaboration with young record producer Bob Ezrin led to the break-through third album “Love It to Death” which hit the charts in 1971, followed by “Killer,” “School’s Out,” ”Billion Dollar Babies,” and “Muscle of Love.” Each new album release was accompanied by a bigger and more elaborate touring stage show. -

Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transport Equity Act: a Legacy for Users 2005

PUBLIC LAW 109–59—AUG. 10, 2005 SAFE, ACCOUNTABLE, FLEXIBLE, EFFICIENT TRANSPORTATION EQUITY ACT: A LEGACY FOR USERS VerDate 14-DEC-2004 12:11 Sep 09, 2005 Jkt 039139 PO 00059 Frm 00001 Fmt 6579 Sfmt 6579 E:\PUBLAW\PUBL059.109 APPS06 PsN: PUBL059 119 STAT. 1144 PUBLIC LAW 109–59—AUG. 10, 2005 Public Law 109–59 109th Congress An Act Aug. 10, 2005 To authorize funds for Federal-aid highways, highway safety programs, and transit [H.R. 3] programs, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of Safe, the United States of America in Congress assembled, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. Transportation Equity Act: A (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Safe, Account- Legacy for Users. able, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Inter- Users’’ or ‘‘SAFETEA–LU’’. governmental (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for this Act relations. 23 USC 101 note. is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. Sec. 2. General definitions. TITLE I—FEDERAL-AID HIGHWAYS Subtitle A—Authorization of Programs Sec. 1101. Authorization of appropriations. Sec. 1102. Obligation ceiling. Sec. 1103. Apportionments. Sec. 1104. Equity bonus program. Sec. 1105. Revenue aligned budget authority. Sec. 1106. Future Interstate System routes. Sec. 1107. Metropolitan planning. Sec. 1108. Transfer of highway and transit funds. Sec. 1109. Recreational trails. Sec. 1110. Temporary traffic control devices. Sec. 1111. Set-asides for Interstate discretionary projects. Sec. 1112. Emergency relief. Sec. 1113. Surface transportation program. Sec. 1114. Highway bridge program. -

Alice Cooper

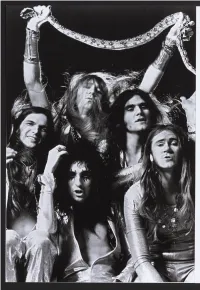

Alice Cooper Alice Cooper, 1972, Photo by Hunter Desportes As the first performer to introduce horror-movie imagery to Hard Rock, pioneering shock rocker Alice Cooper mined social outrage and parental disapproval into transgressive stardom in his 1970s heyday. Cooper’s ghoulish appearance and catchy teen-rebellion anthems—not to mention elaborate his concerts incorporating guillotines, boa constrictors, decapitated baby dolls, and gallons of stage blood—held considerable appeal to middle American teens looking for a musical subculture they could claim entirely as their own. A minister’s son born Vincent Damon Furnier, Cooper was a Detroit native who moved with his family to Phoenix. While in high school there, he formed the Spiders, who cultivated a macabre image and by 1968 had evolved into a band called Alice Cooper. The band was fronted by Furnier, who eventually took the same name as his own. The band moved to Los Angeles before relocating to Detroit, where the band's increasingly outrageous concerts began to generate notoriety. A mainstream breakthrough arrived with the hit 1971 anthem "I'm Eighteen" from the third Alice Cooper album, Love It to Death. The popularity of Love It to Death, and a wildly successful U.K. tour, earned the band a bigger record deal with Warner Bros., who released Killer in late 1971. "School's Out," from the 1972 album of the same name, became Alice's biggest hit to date, while the follow-up, 1973's Billion Dollar Babies, which included the hit "No More Mr. Nice Guy," marked the band's commercial peak. -

Paradox Introduction

THE ECOLOGY OF PARADOX: DISTURBANCE AND RESTORATION IN LAND AND SOUL by Rowland S. Russell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Environmental Studies at Antioch University New England (2007) Committee: Mitchell Thomashow (Chair), John Tallmadge, and Fred Taylor © Copyright by Rowland S. Russell 2007 All Rights Reserved i ABSTRACT This heuristic study explores environmental disturbance and ecological restoration in several North American settings in order to uncover epistemological, philosophical, aesthetic and ethical considerations revolving around those place-based processes. With fire as one of the central metaphors of this work, the initial place-based chapter examines Northern New Mexico's Pajarito Plateau to explore the region's fire ecology. The study then moves to the Pacific Northwest to draw from wild salmon restoration efforts in urban Seattle habitat. The third place-based chapter focuses on the Midwest grass and farmlands in order to investigate the seeming contradictions between managing prairie landscapes for agricultural commodity versus biological diversity. In the final chapter, the metaphorical implications of disturbance and restoration are explored in terms of individuals, communities and as a society. In explicating the philosophical and phenomenological foundations of disturbance and restoration, personal experiences are used in the study as examples to develop applied practice of paradox. It also examines and illuminates correspondences between ecological and eco-psychological cycles of disturbance and restoration within the context of paradox, which for the purpose of this work is defined as any place or context where seemingly contradictory elements coexist without canceling each other out. -

ALICE COOPER: the Studio Albums 1969-1983 Alle Warner Bros.-Alben Von 1969-1983 in Einer 15 CD-Box!

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] ALICE COOPER: The Studio Albums 1969-1983 Alle Warner Bros.-Alben von 1969-1983 in einer 15 CD-Box! Selbst für Rock’n’Roll-Verhältnisse ist ALICE COOPER ein Extrem: Schon in den Sechzigern rüttelte der Mann mit seinem morbiden Outfit, seinen theatralischen Bühnenshows und nicht zuletzt mit hartem Rock an den Gitterstäben des Establishments. Seit seinem Debüt aus dem Jahr 1969 ist Alice Cooper, der eigentlich als Vincent Damon Furnier in Detroit geboren wurde, eine feste Größe im Rock- und Showgeschäft und verkaufte bisher weltweit mehr als 50 Millionen Alben, beeinflusste zahllose Rockbands und wurde 2011 in die Rock and Roll Hall Of Fame aufgenommen. Und er wird noch in diesem Jahr auf eine großangelegte US-Tour mit Mötley Crüe gehen. Mit der 15-CD-Box The Studio Albums 1969-1983 präsentiert Warner Music den perfekten Soundtrack für die schönsten aller Albträume. Alle 15 Warner Bros. Alben wurden im jeweiligen Original-Artwork in einer stabilen Papp- Box zusammengefasst. Das Gesamtpaket steht auch als Download zur Verfügung und umfasst Pretties For You (1969), Easy Action (1970), Love It To Death (1971), Killer (1971), School’s Out (1972), Billion Dollar Babies (1973), Muscle Of Love (1973), Welcome To My Nightmare (1975), Alice Cooper Goes To Hell (1976), Lace And Whiskey (1977), From The Inside (1978), Flush The Fashion (1980), Special Forces (1981), Zipper Catches Skin (1982) und DaDa (1983). Sieben der Alben nahm der Meister zusammen mit den Gitarristen Glen Buxton und Michael Bruce, dem Bassisten Dennis Dunaway und dem Drummer Neal Smith auf, darunter vier Platin-Alben in Folge, die ihren Höhepunkt 1973 mit dem Nummer-1-Album Billion Dollar Babies (Platz 9 in D) fanden. -

Pobierz Ten Artykuł Jako

Sylwetki łowa piosenki „Luney Tune” (auto- tak! Alice Cooper – w rzeczywistości Vin- Impreza nazywa się „Rock Meets Classic”, rzy Alice Cooper i Bruce Dunaway) cent Damon Furnier, urodzony czwarte- a oprócz Coopera wśród wykonawców bio- doskonale określają stylistyczną go lutego 1948 roku w Detroit – jest świet- rących w niej udział znaleźli się: Midge Ure Smanierę jednej z największych gwiazd ame- nym wokalistą, a towarzyszący mu zespół (poprzednio w Ultravox), Joe Lynn Turner rykańskiego rocka. naprawdę potrafi grać. Już sama muzyka (Rainbow) oraz Kim Wilde. Oprawę instru- Bo choć gilotyna, krzesło elektryczne, jest więc atrakcją. Żeby jednak odpo- mentalną zapewniają orkiestry Mat Sinner siekiery czy inne narzędzia, pojawiające się wiednio zilustrować makabryczne teksty Band i Bohemian Symphony Orchestra na scenie w czasie koncertów Alice Coope- piosenek, inna oprawa byłaby nie na miej- z Pragi. ra, wyglądają groźnie, to nikomu krzywdy scu. A czy to wszystko żart? Tak, i to żart A to nie koniec atrakcji, jakie w tym nie robią. Podobnie nie należy się bać kosz- wysokiej próby – wypracowany, efektow- roku przygotował dla fanów mistrz hor- marnych, często ociekających krwią lalek, nie zrealizowany i pasujący do stylistycz- ror-rocka. Zespół Motley Crue zaprosił wijących się ogromnych węży i innych re- nej konwencji jak idealnie dobrane ręka- Coopera do udziału w swej pożegnalnej kwizytów. wiczki. trasie. Wokalista nagrywa też kolejną Właśnie nadarza się okazja, żeby przypo- płytę – tym razem z przebojami innych Aktywność mnieć sylwetkę artysty, a to za sprawą cy- gwiazd. Czy zatem wszystko to konieczne? Czy klicznego tournée, w czasie którego muzycy Sporo, jak na artystę o blisko 50-letnim muzyka nie obroni się sama? Z pewnością rockowi występują z orkiestrą symfoniczną.