Congaree Swamp As a Resource Base for Prehistoric Human Utilization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee

From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Miller, Darcy Shane Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 09:33:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/320030 From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee by Darcy Shane Miller __________________________ Copyright © Darcy Shane Miller 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Darcy Shane Miller, titled From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Vance T. Holliday _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Steven L. Kuhn _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Mary C. Stiner _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) David G. Anderson Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Aartswoud, 210, 211, 213, 217 Abri Dufaure, 221, 225, 257 Abydos

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86617-0 - Birds Dale Serjeantson Index More information INDEX Aartswoud, 210, 211, 213, 217 American coot, 106, 108, 122, 147, 403 Abri Dufaure, 221, 225, 257 American Ornithologist’s Union, 419 Abydos, 245 American Southwest, 177, 189, 193, 289, 291, Acheulian culture, 261 292, 312, 333, 345, 399, 400, 450 Africa, 3, 9, 72, 165, 180, 261, 280, 285, 311, 333. amulet, 200, 201, 226, 227, 229, 359. See also See also North Africa, South Africa, talisman West Africa analogue fauna, 369 African collared dove, 304 Anasazi, 289, 292 African goose. See Chinese goose Anatolia, 271, 320, 337, 354, 359. See also age class, 45–47, 240, 267 Turkey ageing, 35–38, 45, 398. See also fusion, ancient DNA, 34, 285, 292, 314, 396, 399 porosity albatross, 69 bone length, 43, 44, 46, 61 chicken, 69, 268, 273 incremental lines, 40–43 grey geese, 69, 296-297 line of arrested growth (LAG), 40, 42 turkey, 291 Aggersund, 200, 257, 449 Andean condor, 9, 403 agricultural clearance, 315, 365, 374, 377, 385 Anglo-Saxon period, 225, 297, 299, 344, agriculture, 252, 265, 300, 306, 376, 381, 383 364 marginal, 230, 263, 400 Animal Bone Metrical Archive Project, 71, Ain Mallaha, 372 421 Ainu, 206, 336 Antarctica, 14, 252, 266 Ajvide, 51, 154, 221, 259 anthropogenic assemblage, 156 Alabama, 211 recognising, 100, 104, 130–131 Alaska, 14, 195, 210, 226, 246, 363 Apalle Cave, 376, 377 Aldrovandi, 274, 303 Apicius, 341, 343 Aleutian Islands, 204, 214, 216, 226, 231, 252, Aquincum, 342, 351 445 Arabia, 316, 325 Alligator site, 198 archaeological project manager, 84, 343, 397 Alpine chough. -

Climatic Variability at Modoc Rock Shelter (Illinois) and Watson Brake (Louisiana): Biometric and Isotopic Evidence from Archaeological Freshwater Mussel Shell

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2009 Climatic variability at Modoc Rock Shelter (Illinois) and Watson Brake (Louisiana): biometric and isotopic evidence from archaeological freshwater mussel shell Sarah Mistak Caughron Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Caughron, Sarah Mistak, "Climatic variability at Modoc Rock Shelter (Illinois) and Watson Brake (Louisiana): biometric and isotopic evidence from archaeological freshwater mussel shell" (2009). Theses and Dissertations. 1070. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/1070 This Graduate Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATIC VARIABILITY AT MODOC ROCK SHELTER (ILLINOIS) AND WATSON BRAKE (LOUISIANA): BIOMETRIC AND ISOTOPIC EVIDENCE FROM ARCHAEOLOGICAL FRESHWATER MUSSEL SHELL By Sarah Mistak Caughron A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology in the Department of Anthropology and Middle Eastern Cultures Mississippi State, Mississippi December 2009 Copyright 2009 By Sarah Mistak Caughron CLIMATIC VARIABILITY AT MODOC ROCK SHELTER (ILLINOIS) AND WATSON BRAKE (LOUISIANA): BIOMETRIC -

12.9 Kya • Pleistocene Overkill Hypothesis=Overexploitation / Overhun

Review of Last Class Materials (collapses): -Clovis: 12.9 kya Pleistocene Overkill Hypothesis=overexploitation / overhunting of resources by humans Younger Dryas Hypothesis=big game species died due to dropping temperatures so humans changed from clovis tech to more effective tools for their new food sources Was the change human induced or a gradual change via natural causes? -Skara Brae: 2500BC Huge Storm=excellent preservation of artifacts and engulfed in sand Conditions got worse (colder/wetter)=humans forced to migrate slowly to new areas because they couldn’t keep their crops and animals alive/sufficient for their people Was the change gradual or acute/abrupt? -Mohenjo-Daro: No evidence found of defensive/military tools or efforts=easily invaded and taken over Over-exploited resources=upwards of hundreds of city-centers along Indus river that were all trying to grow food for thousands of people which robbed the soil of its nutrients and they could no longer produce food in the quantity needed to keep their populations running Indus river’s tributaries shifted due to massive earthquakes, so the original river dried up and a new one formed east of the old one, so the city-centers had to move too -Ur: Euphrates dried up around 1000BC during the long-term desertification=urban and rural centers both suffered from lack of food, so many small rural populations are thought to have flocked to urban centers for free meals, whether through peaceful trades or harsher means (burning/sacking) -Poverty Point: Climate change=resources -

New Record of Terminal Pleistocene Elk/Wapiti (Cervus Canadensis) from Ohio, USA

2 TERMINAL PLEISTOCENE ELK FROM OHIO VOL. 121(2) New Record of Terminal Pleistocene Elk/Wapiti (Cervus canadensis) from Ohio, USA BRIAN G. REDMOND1, Department of Archaeology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH, USA; DAVID L. DYER, Ohio History Connection, Columbus, OH, USA; and CHARLES STEPHENS, Sugar Creek Chapter, Archaeological Society of Ohio, Massillon, OH, USA. ABSTRACT. The earliest appearance of elk/wapiti (Cervus canadensis) in eastern North America is not thoroughly documented due to the small number of directly dated remains. Until recently, no absolute dates on elk bone older than 10,000 14C yr BP (11,621 to 11,306 calibrated years (cal yr) BP) were known from this region. The partial skeleton of the Tope Elk was discovered in 2017 during commercial excavation of peat deposits from a small bog in southeastern Medina County, Ohio, United States. Subsequent examination of the remains revealed the individual to be a robust male approximately 8.5 years old at death. The large size of this individual is compared with late Holocene specimens and suggests diminution of elk since the late Pleistocene. Two accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon assays on bone collagen samples taken from the scapula and metacarpal of this individual returned ages of 10,270 ± 30 14C yr BP (Beta-477478) (12,154 to 11,835 cal yr BP) and 10,260 ± 30 14C yr BP (Beta-521748) (12,144 to 11,830 cal yr BP), respectively. These results place Cervus canadensis in the terminal Pleistocene of the eastern woodlands and near the establishment of the mixed deciduous forest biome over much of the region. -

A Critical Analysis of the Adoption of Maize in Southern Ontario and Its

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE ADOPTION OF MAIZE IN SOUTHERN ONTARIO AND ITS SPATIAL, DEMOGRAPHIC, AND ECOLOGICAL SIGNATURES A thesis submitted to the Committee of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Eric Beales 2013 Anthropology M.A. Graduate Program January 2014 ABSTRACT: A Critical Analysis of the Adoption of Maize in Southern Ontario and its Spatial, Demographic, and Ecological Signatures Eric Beales This thesis centers on analyzing the spatial, temporal, and ecological patterns associated with the introduction of maize horticulture into Southern Ontario – contextualized against social and demographic models of agricultural transition. Two separate analyses are undertaken: a regional analysis of the spread of maize across the Northeast using linear regression of radiocarbon data and a standard Wave of Advance model; and a local analysis of village locational trends in Southern Ontario using a landscape ecological framework, environmental data and known village sites. Through the integration of these two spatial and temporal scales of analysis, this research finds strong support for both migration and local development. A third model of competition and coalescence is presented to describe the patterning in the data. Keywords: Ontario Archaeology, Spread of Agriculture, Maize, Geostastical Analysis, Geographic Information Systems, GIS, Environmental Modeling, Demographic Modeling, Middle Woodland, Late Woodland, Southern Ontario ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: This study would not have been possible without the generous support of several people and institutions. First and foremost, I would like to express my utmost gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. -

Volume 8 Summer 2016 Numbers 1-2

TENNESSEE ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 8 Summer 2016 Numbers 1-2 EDITORIAL COORDINATORS Michael C. Moore Tennessee Division of Archaeology TENNESSEE ARCHAEOLOGY Kevin E. Smith Middle Tennessee State University VOLUME 8 Summer 2016 NUMBERS 1-2 EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE 1 EDITORS CORNER Paul Avery Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc. 4 The Old Man and the Pleistocene: John Broster and Paleoindian Period Archaeology in the Mid-South – Jared Barrett Introduction to the Special Volume TRC Inc. D. SHANE MILLER AND JESSE W. TUNE Sierra Bow 8 A Retrospective Peek at the Career of John Bertram University of Tennessee Broster Andrew Brown MICHAEL C. MOORE, KEVIN E. SMITH, AARON DETER- University of North Texas WOLF, AND DAVID E. STUART Hannah Guidry 24 The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Record in TRC Inc. Tennessee: A Review of the Tennessee Fluted Point Survey Michaelyn Harle JESSE W. TUNE Tennessee Valley Authority 42 Quantifying Regional Variation in Terminal Phillip Hodge Pleistocene Assemblages from the Lower Tennessee Tennessee Department of Transportation River Valley Using Chert Sourcing RYAN M. PARISH AND ADAM FINN Shannon Hodge Middle Tennessee State University 59 A Preliminary Report on the Late Pleistocene and Sarah Levithol Early Holocene Archaeology of Rock Creek Mortar Tennessee Division of Archaeology Shelter, Upper Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee JAY FRANKLIN, MAUREEN HAYS, FRÉDÉRIC SURMELY, Ryan Parish ILARIA PATANIA, LUCINDA LANGSTON, AND TRAVIS BOW University of Memphis 78 Colonization after Clovis: Using the Ideal Free Tanya M. Peres Distribution to Interpret the Distribution of Late Florida State University Pleistocene and Early Holocene Archaeological Sites in the Duck River Valley, Tennessee Jesse Tune D. SHANE MILLER AND STEPHEN B. -

Evidence from Facing Monday Creek Rockshelter (33Ho414)

LATE WOODLAND HUNTING PATTERNS: EVIDENCE FROM FACING MONDAY CREEK ROCKSHELTER (33HO414), SOUTHEASTERN OHIO A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Staci Elaine Spertzel August 2005 This thesis entitled LATE WOODLAND HUNTING PATTERNS: EVIDENCE FROM FACING MONDAY CREEK ROCKSHELTER (33HO414), SOUTHEASTERN OHIO by STACI ELAINE SPERTZEL has been approved for the Department of Environmental Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences by Elliot Abrams Professor of Sociology and Anthropology Benjamin M. Ogles Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences SPERTZEL, STACI E. M.S. August 2005. Environmental Archaeology Late Woodland Hunting Patterns: Evidence from Facing Monday Creek Rockshelter (33HO414), Southeastern Ohio (122pp.) Director of Thesis: Elliot Abrams Intensified use of southeastern Ohio rockshelter environments during the Late Woodland period is significant to upland resource procurement strategies. Facing Monday Creek Rockshelter (33HO414) of Hocking County serves as one illustration of faunal exploitation and lithic procurement patterns associated with Late Woodland logistical organization. The cultural materials recovered during excavation are analyzed with a purpose of understanding the use of rockshelters as specialized task localities. Results of analyses are synthesized with comparative research to delineate broad cultural patterns associated with rockshelter utilization. A pattern includes intermittent seasonal exploitation by small hunting parties or task groups in search of target resources at a known location. It is hypothesized that during the Late Woodland period, aggregation to larger residential settlements within the broad alluvial valleys would have resulted in an increase in those distances traveled to upland settings initiating a functional attribute for rockshelters as temporary hunting stations. -

Late Paleo-Indian Period Lithic Economies, Mobility, and Group Organization in Wisconsin Ethan Adam Epstein University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Late Paleo-Indian Period Lithic Economies, Mobility, and Group Organization in Wisconsin Ethan Adam Epstein University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Climate Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Epstein, Ethan Adam, "Late Paleo-Indian Period Lithic Economies, Mobility, and Group Organization in Wisconsin" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1361. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1361 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LATE PALEO-INDIAN PERIOD LITHIC ECONOMIES, MOBILITY, AND GROUP ORGANIZATION IN WISCONSIN by Ethan A. Epstein A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology at University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee Fall 2016 ABSTRACT LATE PALEO-INDIAN PERIOD LITHIC ECONOMIES, MOBILITY, AND GROUP ORGANIZATION IN WISCONSIN by Ethan A. Epstein University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Robert J. Jeske The following dissertation focuses upon the organization of Pleistocene / Holocene period lithic technology in Wisconsin circa 10,000 – 10,500 years before present. Lithic debitage and flaked stone tools from the Plainview/Agate Basin components of the Heyrman I site (47DR381), the Dalles site (47IA374), and the Kelly North Tract site at Carcajou Point (47JE02) comprise the data set. These Wisconsin sites are located within a post glacial Great Lakes dune environment, an inland drainage/riverine environment, and an inland wetland/lacustrine environment. -

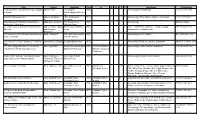

Title Author Publisher Date in V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number

Title Author Publisher Date In V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number Field Manual for Avocational Archaeologists Adams, Nick The Ontario 1994 1 Archaeology, Methodology CC75.5 .A32 1994 in Ontario Archaeological Society Inc. Prehistoric Mesoamerica Adams, Richard E. Little, Brown and 1977 1 Archaeology, Aztec, Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan F1219 .A22 1991 W. Company Lithic Illustration: Drawing Flaked Stone Addington, Lucile R. The University of 1986 Archaeology 000Unavailable Artifacts for Publication Chicago Press The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North Adney, Edwin Tappan Smithsonian Institution 1983 1 Form, Construction, Maritime, Central Canada, E98 .B6 A46 1983 America and Howard I. Press Northwestern Canada, Arctic Chappelle The Knife River Flint Quarries: Excavations Ahler, Stanley A. State Historical Society 1986 1 Archaeology, Lithic, Quarry E78 .N75 A28 1986 at Site 32DU508 of North Dakota The Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Tassili N' Mazonowicz, Douglas Douglas Mazonowicz 1970 1 Archaeology, Rock Art, Sahara, Sandstone N5310.5 .T3 M39 1970 Ajjer The Archeology of Beaver Creek Shelter Alex, Lynn Marie Rocky Mountain Region 1991 Selections form the 3 1 Archaeology, South Dakota, Excavation E78 .S63 A38 1991 (39CU779): A Preliminary Statement National Park Service Division of Cultural Resources People of the Willows: The Prehistory and Ahler, Stanley A., University of North 1991 1 Archaeology, Mandan, North Dakota E99 .H6 A36 1991 Early History of the Hidatsa Indians Thomas D. Thiessen, Dakota Press Michael K. Trimble Archaeological Chemistry -

Late Paleoindian Through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave, Alabama

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-1998 Late Paleoindian through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave, Alabama Renee Beauchamp Walker University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Renee Beauchamp, "Late Paleoindian through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave, Alabama. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1998. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1873 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Renee Beauchamp Walker entitled "Late Paleoindian through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave, Alabama." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Anthropology. Walter E. Klippel, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Paul W. Parmalee, Gerald F. Schroedl, David A. Etnier, Boyce N. Driskell Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Renee Beauchamp Walker entitled "Late Paleoindian through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave , Alabama ." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requi rements for the degree of Doctor of Ph ilosophy, with a ma jor in An thropology . -

The Nature of Prehistory

The Nature of Prehistory In Colorado, mountains ascended past clouds and were eroded to valleys, salty seas flooded our land and were dried to powder or rested on us as freshwater ice, plants rose from wet algae to dry forests and flowers, animals transformed from a single cell to frantic dinosaurs and later, having rotated around a genetic rocket, into sly mammals. No human saw this until a time so very recent that we were the latest model of Homo sapiens and already isolated from much of the terror of that natural world by our human cultures' perceptual permutations and re flections. We people came late to Colorado. The first humans, in the over one hundred thousand square miles of what we now call Colorado, saw a landscape partitioned not by political fences or the orthogonal architecture of wall, floor, and roadway, but by gradations in game abundance, time to water, the supply of burnables, shelter from vagaries of atmosphere and spirit, and a pedestrian's rubric of distance and season. We people came as foragers and hunters to Colorado. We have lived here only for some one hundred fifty centuries-not a long time when compared to the fifty thousand centuries that the Euro pean, African, and Asian land masses have had us and our immediate prehuman ancestors. It is not long compared to the fifty million cen turies of life on the planet. We humans, even the earliest prehistoric The Na ture of Prehistory 3 societies, are all colonists in Colorado. And, except for the recent pass ing of a mascara of ice and rain, we have not been here long enough to see, or study, her changing face.