A Critical Analysis of the Adoption of Maize in Southern Ontario and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12.9 Kya • Pleistocene Overkill Hypothesis=Overexploitation / Overhun

Review of Last Class Materials (collapses): -Clovis: 12.9 kya Pleistocene Overkill Hypothesis=overexploitation / overhunting of resources by humans Younger Dryas Hypothesis=big game species died due to dropping temperatures so humans changed from clovis tech to more effective tools for their new food sources Was the change human induced or a gradual change via natural causes? -Skara Brae: 2500BC Huge Storm=excellent preservation of artifacts and engulfed in sand Conditions got worse (colder/wetter)=humans forced to migrate slowly to new areas because they couldn’t keep their crops and animals alive/sufficient for their people Was the change gradual or acute/abrupt? -Mohenjo-Daro: No evidence found of defensive/military tools or efforts=easily invaded and taken over Over-exploited resources=upwards of hundreds of city-centers along Indus river that were all trying to grow food for thousands of people which robbed the soil of its nutrients and they could no longer produce food in the quantity needed to keep their populations running Indus river’s tributaries shifted due to massive earthquakes, so the original river dried up and a new one formed east of the old one, so the city-centers had to move too -Ur: Euphrates dried up around 1000BC during the long-term desertification=urban and rural centers both suffered from lack of food, so many small rural populations are thought to have flocked to urban centers for free meals, whether through peaceful trades or harsher means (burning/sacking) -Poverty Point: Climate change=resources -

New Record of Terminal Pleistocene Elk/Wapiti (Cervus Canadensis) from Ohio, USA

2 TERMINAL PLEISTOCENE ELK FROM OHIO VOL. 121(2) New Record of Terminal Pleistocene Elk/Wapiti (Cervus canadensis) from Ohio, USA BRIAN G. REDMOND1, Department of Archaeology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH, USA; DAVID L. DYER, Ohio History Connection, Columbus, OH, USA; and CHARLES STEPHENS, Sugar Creek Chapter, Archaeological Society of Ohio, Massillon, OH, USA. ABSTRACT. The earliest appearance of elk/wapiti (Cervus canadensis) in eastern North America is not thoroughly documented due to the small number of directly dated remains. Until recently, no absolute dates on elk bone older than 10,000 14C yr BP (11,621 to 11,306 calibrated years (cal yr) BP) were known from this region. The partial skeleton of the Tope Elk was discovered in 2017 during commercial excavation of peat deposits from a small bog in southeastern Medina County, Ohio, United States. Subsequent examination of the remains revealed the individual to be a robust male approximately 8.5 years old at death. The large size of this individual is compared with late Holocene specimens and suggests diminution of elk since the late Pleistocene. Two accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon assays on bone collagen samples taken from the scapula and metacarpal of this individual returned ages of 10,270 ± 30 14C yr BP (Beta-477478) (12,154 to 11,835 cal yr BP) and 10,260 ± 30 14C yr BP (Beta-521748) (12,144 to 11,830 cal yr BP), respectively. These results place Cervus canadensis in the terminal Pleistocene of the eastern woodlands and near the establishment of the mixed deciduous forest biome over much of the region. -

Volume 8 Summer 2016 Numbers 1-2

TENNESSEE ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 8 Summer 2016 Numbers 1-2 EDITORIAL COORDINATORS Michael C. Moore Tennessee Division of Archaeology TENNESSEE ARCHAEOLOGY Kevin E. Smith Middle Tennessee State University VOLUME 8 Summer 2016 NUMBERS 1-2 EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE 1 EDITORS CORNER Paul Avery Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc. 4 The Old Man and the Pleistocene: John Broster and Paleoindian Period Archaeology in the Mid-South – Jared Barrett Introduction to the Special Volume TRC Inc. D. SHANE MILLER AND JESSE W. TUNE Sierra Bow 8 A Retrospective Peek at the Career of John Bertram University of Tennessee Broster Andrew Brown MICHAEL C. MOORE, KEVIN E. SMITH, AARON DETER- University of North Texas WOLF, AND DAVID E. STUART Hannah Guidry 24 The Paleoindian and Early Archaic Record in TRC Inc. Tennessee: A Review of the Tennessee Fluted Point Survey Michaelyn Harle JESSE W. TUNE Tennessee Valley Authority 42 Quantifying Regional Variation in Terminal Phillip Hodge Pleistocene Assemblages from the Lower Tennessee Tennessee Department of Transportation River Valley Using Chert Sourcing RYAN M. PARISH AND ADAM FINN Shannon Hodge Middle Tennessee State University 59 A Preliminary Report on the Late Pleistocene and Sarah Levithol Early Holocene Archaeology of Rock Creek Mortar Tennessee Division of Archaeology Shelter, Upper Cumberland Plateau, Tennessee JAY FRANKLIN, MAUREEN HAYS, FRÉDÉRIC SURMELY, Ryan Parish ILARIA PATANIA, LUCINDA LANGSTON, AND TRAVIS BOW University of Memphis 78 Colonization after Clovis: Using the Ideal Free Tanya M. Peres Distribution to Interpret the Distribution of Late Florida State University Pleistocene and Early Holocene Archaeological Sites in the Duck River Valley, Tennessee Jesse Tune D. SHANE MILLER AND STEPHEN B. -

Evidence from Facing Monday Creek Rockshelter (33Ho414)

LATE WOODLAND HUNTING PATTERNS: EVIDENCE FROM FACING MONDAY CREEK ROCKSHELTER (33HO414), SOUTHEASTERN OHIO A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Staci Elaine Spertzel August 2005 This thesis entitled LATE WOODLAND HUNTING PATTERNS: EVIDENCE FROM FACING MONDAY CREEK ROCKSHELTER (33HO414), SOUTHEASTERN OHIO by STACI ELAINE SPERTZEL has been approved for the Department of Environmental Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences by Elliot Abrams Professor of Sociology and Anthropology Benjamin M. Ogles Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences SPERTZEL, STACI E. M.S. August 2005. Environmental Archaeology Late Woodland Hunting Patterns: Evidence from Facing Monday Creek Rockshelter (33HO414), Southeastern Ohio (122pp.) Director of Thesis: Elliot Abrams Intensified use of southeastern Ohio rockshelter environments during the Late Woodland period is significant to upland resource procurement strategies. Facing Monday Creek Rockshelter (33HO414) of Hocking County serves as one illustration of faunal exploitation and lithic procurement patterns associated with Late Woodland logistical organization. The cultural materials recovered during excavation are analyzed with a purpose of understanding the use of rockshelters as specialized task localities. Results of analyses are synthesized with comparative research to delineate broad cultural patterns associated with rockshelter utilization. A pattern includes intermittent seasonal exploitation by small hunting parties or task groups in search of target resources at a known location. It is hypothesized that during the Late Woodland period, aggregation to larger residential settlements within the broad alluvial valleys would have resulted in an increase in those distances traveled to upland settings initiating a functional attribute for rockshelters as temporary hunting stations. -

The Nature of Prehistory

The Nature of Prehistory In Colorado, mountains ascended past clouds and were eroded to valleys, salty seas flooded our land and were dried to powder or rested on us as freshwater ice, plants rose from wet algae to dry forests and flowers, animals transformed from a single cell to frantic dinosaurs and later, having rotated around a genetic rocket, into sly mammals. No human saw this until a time so very recent that we were the latest model of Homo sapiens and already isolated from much of the terror of that natural world by our human cultures' perceptual permutations and re flections. We people came late to Colorado. The first humans, in the over one hundred thousand square miles of what we now call Colorado, saw a landscape partitioned not by political fences or the orthogonal architecture of wall, floor, and roadway, but by gradations in game abundance, time to water, the supply of burnables, shelter from vagaries of atmosphere and spirit, and a pedestrian's rubric of distance and season. We people came as foragers and hunters to Colorado. We have lived here only for some one hundred fifty centuries-not a long time when compared to the fifty thousand centuries that the Euro pean, African, and Asian land masses have had us and our immediate prehuman ancestors. It is not long compared to the fifty million cen turies of life on the planet. We humans, even the earliest prehistoric The Na ture of Prehistory 3 societies, are all colonists in Colorado. And, except for the recent pass ing of a mascara of ice and rain, we have not been here long enough to see, or study, her changing face. -

TABLE 6.3 Significant Archaeological Sites in North America Older Than 5,000 Years

TABLE 6.3 Significant Archaeological Sites in North America Older than 5,000 Years Site Name Description Bluefish Located in present-day Yukon Territory, Bluefish Caves is significant because it provides Caves evidence of people in Beringia during the last ice age. The site contains artifacts made of stone and bone as well as butchered animal remains. Most archaeologists accept dates between 15,000 and 12,000 years ago, although some suggest dates in the range of 25,000 years ago. Cactus Hill This site is located in Virginia. It is widely accepted as being older than 12,000 years, but the precise antiquity is uncertain. Some suggest that the site may be as old as 19,000 to 17,000 years, but these dates are contested. Gault This site, located in Texas, was a Clovis camp and was likely first occupied more than 12,000 years ago. The assemblage includes more than one million artifacts, includ- ing several hundred thousand that are more than 9,000 years old. The site is particularly significant for showing the diversity of diet, which, contrary to popular belief, indicates that mammoths and other large game were only a small part of the Clovis diet. The site is also significant in providing what may be the oldest art in North America, in the form of more than 100 incised stones. Meadowcroft Meadowcroft Rockshelter, located in Pennsylvania, is widely considered to contain depos- its that are at least 12,000 years old. Some suggest the deposits may be as old as 19,000 years, but these dates are contested. -

Archaeological Survey of the Chesapeake Bay Shorelines Associated with Accomack County and Northampton County, Virginia

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY SHORELINES ASSOCIATED WITH ACCOMACK COUNTY AND NORTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA VOLUME I By: Darrin Lowery Manuscript Prepared For: The Virginia Department of Historic Resources Portsmouth Regional Preservation Office 612 Court Street Portsmouth, VA 23704 March 2001 ii ABSTRACT This report summarizes the results of an archaeological survey conducted along the Chesapeake Bay shorelines of both Accomack County and Northampton County, Virginia. Accomack and Northampton counties represent the southernmost extension of the Delmarva Peninsula. The study area encompasses the confluence of the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. A shoreline survey was conducted along the Chesapeake Bay to gauge the erosion threat to the archaeological resources situated along the shoreline. Archaeological sites along shorelines are subjected to numerous natural processes. Aside from erosion, some of the natural processes influencing shoreline related cultural resources include coastal inundation, prehistoric aeolian processes, bioturbation, recent coastal dune formations, chemical processes within tidal marshes, redeposition, and surface “sheet-erosion” or deflation. These natural processes greatly influence the success of an archaeological survey and what data are collected, noted, and observed while conducting a survey. Summaries associated with these natural processes are presented in this report. The report also offers examples, using Delmarva Peninsula archaeological data, which illustrate how these natural processes influence and limit the interpretive value of single analysis or one-time archaeological survey surface data. As a “double-blind” test, the actual locations and cultural chronologies associated with previously recognized and recorded sites were not collected prior to the completion of the survey. By not knowing the previous site data, the present shoreline survey would help assess and gauge the accuracy of the previous single “one-time” archaeological survey data. -

Arqueologia 89

www.porticolibrerias.es Nº 702 PÓRTICOSemanal Arqueología 89 10 octubre 2005 Responsable de la Sección: Carmen Alcrudo Dirige: José Miguel Alcrudo METODOLOGÍA: 001 — 026 PREHISTORIA. Obras generales: 027 — 053 Paleolítico — Neolítico: 054 — 073 Edad de los metales: 074 — 091 Península Ibérica: 092 — 113 ARQUEOLOGÍA. Obras generales: 114 — 134 Oriente: 135 — 148 Grecia: 149 — 162 Roma: 163 — 207 Península Ibérica: 208 — 220 Medieval: 221 — 239 EPIGRAFÍA — NUMISMÁTICA: 240 — 246 METODOLOGÍA 001 Albore Livadie, C. / F. Ortolani, eds.: Il sistema uomo-ambiente tra passato e presente 1998 – 322 pp., fig. € 44,95 002 Brather, S.: Ethnische Interpretationen in der frühgeschichtlichen Archäo- logie. Geschichte, Grundlagen und Alternativen 2004 – x + 807 pp., 94 fig. € 198,00 INDICE: 1. Fragestellung: «ethnische Interpretation» und «ethnische Identität» — 2. Geschichte: ethnische Interpretationen im nationalen Diskurs des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts — 3. Begriffe: zentrale Klassifikationen im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert: Das «Volk» — Die «Kultur» — Die «Rasse» — Die «Sprache» — 4. Identitäten: sociale und ethnische Gruppen: Kollektive Identitäten als soziale PÓRTICO LIBRERÍAS PS 702 — Arqueología 89 2 Konstrukte — Ethnische Identitäten und kulturelles Gedächtnis — Barbaren in der antiken Ethnogra- phie: Kelten, Germanen und Slawen — Ethnische Identitäten im frühen Mittelalter: germanische «Reichsbildungen» — 5. Traditionelle Ansätze: ethnische Interpretationen in der frühgeschichtlichen Archäologie: Ausgangspunkt: regionale Abgrenzungen und Siedlungsgebiete -

Megafloods and Clovis Cache at Wenatchee, Washington

Quaternary Research 85 (2016) 430e444 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Research journal homepage: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/quaternary-research Megafloods and Clovis cache at Wenatchee, Washington Richard B. Waitt U.S. Geological Survey, 1300 SE Cardinal Court, #100, Vancouver, WA 98683, USA article info abstract Article history: Immense late Wisconsin floods from glacial Lake Missoula drowned the Wenatchee reach of Wash- Received 17 June 2015 ington's Columbia valley by different routes. The earliest debacles, nearly 19,000 cal yr BP, raged 335 m deep down the Columbia and built high Pangborn bar at Wenatchee. As advancing ice blocked the northwest of Columbia valley, several giant floods descended Moses Coulee and backflooded up the Keywords: Columbia past Wenatchee. Ice then blocked Moses Coulee, and Grand Coulee to Quincy basin became the fl Missoula oods westmost floodway. From Quincy basin many Missoula floods backflowed 50 km upvalley to Wenatchee Clovis d fl 18,000 to 15,500 years ago. Receding ice dammed glacial Lake Columbia centuries more till it burst Mega oods fl Columbia valley about 15,000 years ago. After Glacier Peak ashfall about 13,600 years ago, smaller great ood(s) swept down the Columbia from glacial Lake Kootenay in British Columbia. The East Wenatchee cache of huge fluted Clovis points had been laid atop Pangborn bar after the Glacier Peak ashfall, then buried by loess. Clovis people came five and a half millennia after the early gigantic Missoula floods, two and a half millennia after the last small Missoula flood, and two millennia after the glacial Lake Columbia flood. -

Geology and Archaeology of Meadowcroft Rockshelter and the Multiple Ice Ages of Southwestern Pennsylvania

GEOLOGY AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEADOWCROFT ROCKSHELTER Meadowcroft Rockshelter (photo from Anonymous, 2018b). AND THE MULTIPLE ICE AGES OF SOUTHWESTERN PENNSYLVANIA Pittsburgh Geological Society Field Trip September 7, 2019 Guidebook PGS Spring Field Trip September 7, 2019 Geology and Archaeology of Meadowcroft Rockshelter and the Multiple Ice Ages of Southwestern Pennsylvania Trip Leaders: Mary Ann Gross, Range Resources—Appalachia John A. Harper, Carnegie Museum of Natural History Albert D. Kollar, Carnegie Museum of Natural History i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 The Pleistocene in southwestern Pennsylvania ................................................................. 2 Pennsylvanian climate-driven sedimentary cycles with emphasis on the Monongahela Formation ...................................................................................... 12 Road log ........................................................................................................................ 20 Stop 1. Meadowcroft Historic Village and Visitor Center ......................................... 23 Stop 2. Meadowcroft Rockshelter ......................................................................... 25 Stop 3. Cross Creek County Park – lunch .............................................................. 36 Stop 4. Tour of MarkWest Houston, PA plant ......................................................... 38 Stop 5. Former Pleistocene -

Ethnographic Landscape Study Northwest Piceance Creek Basin for the White River Field Office Bureau of Land Management Rio Blanco County, Colorado Section 1

ETHNOGRAPHIC LANDSCAPE STUDY NORTHWEST PICEANCE CREEK BASIN FOR THE WHITE RIVER FIELD OFFICE BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT RIO BLANCO COUNTY, COLORADO SECTION 1 30 SEPTEMBER 2016 GRAND RIVER INSTITUTE FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY: DISCLOSURE OF SITE LOCATIONS IS PROHIBITED (43 CFR 7.18) ETHNOGRAPHIC LANDSCAPE STUDY NORTHWEST PICEANCE CREEK BASIN FOR THE WHITE RIVER FIELD OFFICE BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT RIO BLANCO COUNTY, COLORADO GRI Project No. 2016-20 30 September 2016 Prepared by Carl E. Conner, Michael Berry, Nicky Pham, Masha Ryabkova Jessica Yaquinto and Richard Ott with geomorphology sections derived from documents by James C. Miller, and the rock art introduction by Sally Cole ] GRAND RIVER INSTITUTE ] P.O. Box 3543 Grand Junction, Colorado 81502 BLM Antiquities Permit No. C-52775 Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT WHITE RIVER FIELD OFFICE 220 East Market Street Meeker, Colorado 81641 ABSTRACT This report is written in partial satisfaction of Purchase Order L15PX01787 administered by the Colorado State Office of the Bureau of Land Management. It is Part I of an Ethnographic Landscape Study of the Northwest Piceance Creek Basin, an area that was an essential portion of the traditional Ute homeland during the historic period. This area has importance for other tribal groups as well; however, this study’s focus is on the Utes and how they see themselves as connected to this landscape. Information gathered by this inquiry will benefit the Bureau of Land Management’s White River Field Office in managing cultural resources in the Piceance Basin in light of intense oil and gas development along with other uses such as grazing, wild horse management, and fire management. -

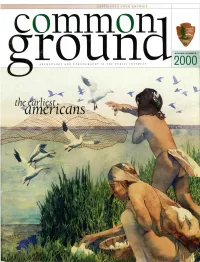

SPRING/SUMMER 2000 Groun^F ^^^^K a R ( II ! O I 0 G Y a \ D E T II N O G R a PHY in Till PUBLIC I N I I R I Ds I

commonEXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA i SPRING/SUMMER 2000 groun^f ^^^^k A R ( II ! O I 0 G Y A \ D E T II N O G R A PHY IN Till PUBLIC I N I I R I dS I theamencans earliest .^s^ Common Ground has been in the shop this summer, getting a new coat of paint. This issue, the first in color, marks changes that have been on the boards for almost a year, including an overhaul of our web site to be unveiled this winter (previewed opposite). The shift acknowledges that communications today must be sophisticated in strategy to cut through the media clatter. The tack was timed to take advantage of the recent Harris poll on archeology, sponsored by the NPS Archeology and private sector. Through the web and other means, we'll be tak Ethnography Program-this magazine's publisher-and the ing that message to an even wider audience. nation's top archeological organizations. Over the coming year, In the last issue of Common Ground, Interior Secretary Bruce poll results in hand, we'll be spotlighting archeological projects Babbitt said public neglect was the number one threat to carried out thanks to preservation law-to heighten awareness archeological sites, but he could have been talking about any of of the profession and the fragile resources in our care. As report the resources under our stewardship. "Neglect feeds all the ed in the last issue, the poll shows that most Americans, other threats," he said. "If we don't have an interested and although they have a fairly good grasp of the discipline, have informed public, the loss goes by unnoticed." Message project major misconceptions as well.