With SL4A Paul Ferrill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Source Used in DNAC-Wide Area Bonjour Magneto

Open Source Used In DNAC-Wide Area Bonjour Magneto Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. Text Part Number: 78EE117C99-1090203837 Open Source Used In DNAC-Wide Area Bonjour Magneto 1 This document contains licenses and notices for open source software used in this product. With respect to the free/open source software listed in this document, if you have any questions or wish to receive a copy of any source code to which you may be entitled under the applicable free/open source license(s) (such as the GNU Lesser/General Public License), please contact us at [email protected]. In your requests please include the following reference number 78EE117C99-1090203837 Contents 1.1 javax-activation 1.2.0 1.1.1 Available under license 1.2 metrics-servlets 3.1.0 1.3 mongodb-driver 3.0.4 1.4 jaxb-core 2.3.0 1.4.1 Available under license 1.5 antlr 2.7.6 1.5.1 Available under license 1.6 spring-boot-autoconfigure 1.5.12.RELEASE 1.7 spring-instrument 4.3.19.RELEASE 1.7.1 Available under license 1.8 nimbus-jose-jwt 4.3.1 1.9 javax-inject 1 1.9.1 Available under license 1.10 json-smart 1.3.1 1.11 opentracing-util 0.31.0 1.12 xpp3-min 1.1.3.4.O 1.12.1 Notifications 1.12.2 Available under license 1.13 ojdbc 6 1.14 jax-ws-api 2.3.0 1.15 aspect-j 1.9.2 1.15.1 Available under license 1.16 jetty-util 9.3.27.v20190418 1.17 unirest-java 1.4.5 1.18 jetty-continuation 9.3.27.v20190418 Open Source Used In -

Nyon Driftsanvisning Online-Version Sv Bruksanvisning I Original

Nyon Driftsanvisning Online-version sv Bruksanvisning i original 1 270 020 Wsv (2017.07) T / 68 2 Innehållsförteckning Säkerhetsanvisningar . 5 Allmänna säkerhetsanvisningar . 5 Säkerhetsanvisningar för eBikes . 6 Säkerhetsanvisningar i samband med navigeringen . 8 Hjärtliga gratulationer . 9 Uppdateringar . 9 De första stegen . 10 Manöversystemet ”Nyon” . 12 Premiumfunktioner . 13 Smartphone-kompatibilitet . 14 Manövrering . 15 Huvudmeny . 16 Driftstart . 17 Förutsättningar . 17 In-/urkoppling av elcykelsystemet . 17 Sätta in och ta ut cykeldatorn . 18 Sätta/stänga av cykeldatorn . 18 Energiförsörjning av externa enheter via USB-kontaktdonet . 19 Idrifttagning av cykeldatorn . 19 Inloggning i cykeldatorn . 20 Anslut hjärtfrekvensbältet till Nyon . 21 1 270 020 Wsv | (19.7.17) Bosch eBike Systems 3 Drift . 22 Visningar och inställningar av cykeldatorn . 22 Driftsläge ”Dashboard” . 22 Driftsläge ”Ride” . 24 Driftsläge ”Karta & navigation” . 26 Driftsläge ”Fitness” . 30 Driftsläge ”Inställningar” . 32 Statusvisningar . 34 Cykeldatorns energiförsörjning . 35 Återställa Nyon . 35 Indikering av batteriets laddningstillstånd . 36 Inställning av assistansgrad . 37 In-/urkoppling av ledhjälp . 39 Tända/släcka cykelbelysning . 39 eShift (tillval) . 40 Visningar och inställningar av Smartphone-applikationen ”Bosch eBike Connect” . 41 Aktivering av applikationen ”Bosch eBike Connect” . 42 Registrering via Smartphone och Bluetooth®-koppling . 43 Huvudmeny till ”Bosch eBike Connect” . 44 Menypunkt ”Dashboard” . 45 Menypunkt ”Aktiviteter” . 46 Menypunkt ”Karta” . 47 Menypunkt ”Butik” . 48 Menypunkt ”Inställningar” . 49 Överföring av kartorna till Nyon . 51 Menypunkt ”Hjälp” . 52 Bosch eBike Systems 1 270 020 Wsv | (19.7.17) 4 Visningar och inställningar på online-portalen . 53 Online-registrering . 53 Huvudmeny online-portal . 54 Menypunkt ”Scrivboard” . 54 Menypunkt ”Ruttplanering” . 55 Importera GPX-track . 56 Menypunkt ”Aktiviteter” . 57 Menypunkt ”eBike System” . 58 Menypunkt ”Hjälp” . 58 Menypunkten ”Profil” . -

Chapter 12 Calc Macros Automating Repetitive Tasks Copyright

Calc Guide Chapter 12 Calc Macros Automating repetitive tasks Copyright This document is Copyright © 2019 by the LibreOffice Documentation Team. Contributors are listed below. You may distribute it and/or modify it under the terms of either the GNU General Public License (http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html), version 3 or later, or the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), version 4.0 or later. All trademarks within this guide belong to their legitimate owners. Contributors This book is adapted and updated from the LibreOffice 4.1 Calc Guide. To this edition Steve Fanning Jean Hollis Weber To previous editions Andrew Pitonyak Barbara Duprey Jean Hollis Weber Simon Brydon Feedback Please direct any comments or suggestions about this document to the Documentation Team’s mailing list: [email protected]. Note Everything you send to a mailing list, including your email address and any other personal information that is written in the message, is publicly archived and cannot be deleted. Publication date and software version Published December 2019. Based on LibreOffice 6.2. Using LibreOffice on macOS Some keystrokes and menu items are different on macOS from those used in Windows and Linux. The table below gives some common substitutions for the instructions in this chapter. For a more detailed list, see the application Help. Windows or Linux macOS equivalent Effect Tools > Options menu LibreOffice > Preferences Access setup options Right-click Control + click or right-click -

Administration and Configuration Guide

Red Hat JBoss Data Virtualization 6.4 Administration and Configuration Guide This guide is for administrators. Last Updated: 2018-09-26 Red Hat JBoss Data Virtualization 6.4 Administration and Configuration Guide This guide is for administrators. Red Hat Customer Content Services Legal Notice Copyright © 2018 Red Hat, Inc. This document is licensed by Red Hat under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. If you distribute this document, or a modified version of it, you must provide attribution to Red Hat, Inc. and provide a link to the original. If the document is modified, all Red Hat trademarks must be removed. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, OpenShift, Fedora, the Infinity logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Linux ® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java ® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS ® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL ® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. Node.js ® is an official trademark of Joyent. Red Hat Software Collections is not formally related to or endorsed by the official Joyent Node.js open source or commercial project. -

Common Tools for Team Collaboration Problem: Working with a Team (Especially Remotely) Can Be Difficult

Common Tools for Team Collaboration Problem: Working with a team (especially remotely) can be difficult. ▹ Team members might have a different idea for the project ▹ Two or more team members could end up doing the same work ▹ Or a few team members have nothing to do Solutions: A combination of few tools. ▹ Communication channels ▹ Wikis ▹ Task manager ▹ Version Control ■ We’ll be going in depth with this one! Important! The tools are only as good as your team uses them. Make sure all of your team members agree on what tools to use, and train them thoroughly! Communication Channels Purpose: Communication channels provide a way to have team members remotely communicate with one another. Ideally, the channel will attempt to emulate, as closely as possible, what communication would be like if all of your team members were in the same office. Wait, why not email? ▹ No voice support ■ Text alone is not a sufficient form of communication ▹ Too slow, no obvious support for notifications ▹ Lack of flexibility in grouping people Tools: ▹ Discord ■ discordapp.com ▹ Slack ■ slack.com ▹ Riot.im ■ about.riot.im Discord: Originally used for voice-chat for gaming, Discord provides: ▹ Voice & video conferencing ▹ Text communication, separated by channels ▹ File-sharing ▹ Private communications ▹ A mobile, web, and desktop app Slack: A business-oriented text communication that also supports: ▹ Everything Discord does, plus... ▹ Threaded conversations Riot.im: A self-hosted, open-source alternative to Slack Wikis Purpose: Professionally used as a collaborative game design document, a wiki is a synchronized documentation tool that retains a thorough history of changes that occured on each page. -

Sistemas De Control De Versiones De Última Generación (DCA)

Tema 10 - Sistemas de Control de Versiones de última generación (DCA) Antonio-M. Corbí Bellot Tema 10 - Sistemas de Control de Versiones de última generación (DCA) II HISTORIAL DE REVISIONES NÚMERO FECHA MODIFICACIONES NOMBRE Tema 10 - Sistemas de Control de Versiones de última generación (DCA) III Índice 1. ¿Qué es un Sistema de Control de Versiones (SCV)?1 2. ¿En qué consiste el control de versiones?1 3. Conceptos generales de los SCV (I) 1 4. Conceptos generales de los SCV (II) 2 5. Tipos de SCV. 2 6. Centralizados vs. Distribuidos en 90sg 2 7. ¿Qué opciones tenemos disponibles? 2 8. ¿Qué podemos hacer con un SCV? 3 9. Tipos de ramas 3 10. Formas de integrar una rama en otra (I)3 11. Formas de integrar una rama en otra (II)4 12. SCV’s con los que trabajaremos 4 13. Git (I) 5 14. Git (II) 5 15. Git (III) 5 16. Git (IV) 6 17. Git (V) 6 18. Git (VI) 7 19. Git (VII) 7 20. Git (VIII) 7 21. Git (IX) 8 22. Git (X) 8 23. Git (XI) 9 Tema 10 - Sistemas de Control de Versiones de última generación (DCA) IV 24. Git (XII) 9 25. Git (XIII) 9 26. Git (XIV) 10 27. Git (XV) 10 28. Git (XVI) 11 29. Git (XVII) 11 30. Git (XVIII) 12 31. Git (XIX) 12 32. Git. Vídeos relacionados 12 33. Mercurial (I) 12 34. Mercurial (II) 12 35. Mercurial (III) 13 36. Mercurial (IV) 13 37. Mercurial (V) 13 38. Mercurial (VI) 14 39. -

Useful Tools for Game Making

CMS.611J/6.073 Fall 2014 Useful Tools List This list is by no means complete, but should get you started. Talk to other folks in the class about their recommendations. Revision Control Version control software, provides backups and easy reversion. Perforce Mac/Win GUI (p4v): Heavily used in game http://www.perforce.com/dow industry. Commercial nloads/Perforce-Software-Ver software; you can use the sion-Management/complete_l Game Lab server. ist/Customer Subversion Command line: Open source, server-based http://subversion.apache.org/ Windows GUI: http://tortoisesvn.net/ Git Command line: Open source, distributed http://git-scm.com/ Mercurial Command line: Open source, distributed http://mercurial.selenic.com/ Windows GUI: http://tortoisehg.bitbucket.org/ SourceTree Mac/Win GUI: Not a source control system, http://www.sourcetreeapp.co just a GUI for Git and m/ Mercurial clients Revision Control Hosting SourceForge http://sourceforge.net/ git, mercurial, or subversion BitBucket https://bitbucket.org/ git or mercurial GitHub https://github.com/ git, has own (painful) GUI for Git 1 Image Editing MSPaint Windows, pre-installed Surprisingly useful quick pixel art editor (esp for prototypes) Paint.NET Windows, About as easy as MSPaint, but http://www.getpaint.net/download much more powerful .html Photoshop Mac, Windows New Media Center, 26-139 GIMP Many platforms, Easier than photoshop, at http://www.gimp.org/downloads/ least. Sound GarageBand Mac New Media Center, 26-139 Audacity Many platforms, Free, open source. http://audacity.sourceforge.ne -

Enable Mobile Ecosystem on Intel Platforms

Mobility Ecosystem business models and ecosystem in change Oliver Buschmann October 22, 2013 Intel confidential — Do Not Forward Key ecosystem & business model changes Android rising Verticali- Device zation & composition UX race China low- ‘Subsidizers’ cost emerging Intel confidential History of Smartphone ecosystem disruption Symbian iOS Blackberry Palm Android Windows Disruption Disruption Wave 2 Disruption Wave 1 Low Cost Wave 3? Integration Modular 3 Intel confidential Ecosytems verticalize with different Business Monetization Data & Transaction Revenue Advertizing Adv / ~$44B Search: Ads, Web Svc: Transaction $3 B $3 B Apps & Revenue SW & Content: $12B Media, eCom. Services ~$20 B Apps : $ND Revenue Apps : Applicat.: ~$1B $27 B OS OS $30 B Consoles, Device Devices Devices SP, Tb, Wb: Tablets Hardware $145 B $104B $5B $13 B Si & Mfg Si Revenue $14 B Revenue Legend: Observed/Company reported Supposition Core monetization area 4 Intel confidential The race for best User Experience Leadership capable today Solution in market, not currently leadershipNo solution in market or limited 2013 UX Ecosystem Landscape traction/capability Capability Intel Apple Google Microsoft Samsung Qualcomm Personal Nuance Genie Siri Google Now N/A – Bing S-Voice Platform focus Assistant Intel PA Notifications Wallet Nuance Bing HW accel Speech / NLU Siri / Nuance Google Voice S-Voice / Nuance HW accel, LPAL Tell Me LPAL Personal Personal Assistant Location Intel LBS, Chipset Maps Maps Maps CSR / Android iZat Context CSP, Sensor Hub Siri Google Now Context -

Java Programming Language Family Godiva Scala Processing Aspectj Groovy Javafx Script Einstein J Sharp Judoscript Jasmin Beanshell

JAVA PROGRAMMING LANGUAGE FAMILY GODIVA SCALA PROCESSING ASPECTJ GROOVY JAVAFX SCRIPT EINSTEIN J SHARP JUDOSCRIPT JASMIN BEANSHELL PDF-33JPLFGSPAGJSEJSJJB16 | Page: 133 File Size 5,909 KB | 10 Oct, 2020 PDF File: Java Programming Language Family Godiva Scala Processing Aspectj Groovy Javafx Script 1/3 Einstein J Sharp Judoscript Jasmin Beanshell - PDF-33JPLFGSPAGJSEJSJJB16 TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction Brief Description Main Topic Technical Note Appendix Glossary PDF File: Java Programming Language Family Godiva Scala Processing Aspectj Groovy Javafx Script 2/3 Einstein J Sharp Judoscript Jasmin Beanshell - PDF-33JPLFGSPAGJSEJSJJB16 Java Programming Language Family Godiva Scala Processing Aspectj Groovy Javafx Script Einstein J Sharp Judoscript Jasmin Beanshell e-Book Name : Java Programming Language Family Godiva Scala Processing Aspectj Groovy Javafx Script Einstein J Sharp Judoscript Jasmin Beanshell - Read Java Programming Language Family Godiva Scala Processing Aspectj Groovy Javafx Script Einstein J Sharp Judoscript Jasmin Beanshell PDF on your Android, iPhone, iPad or PC directly, the following PDF file is submitted in 10 Oct, 2020, Ebook ID PDF-33JPLFGSPAGJSEJSJJB16. Download full version PDF for Java Programming Language Family Godiva Scala Processing Aspectj Groovy Javafx Script Einstein J Sharp Judoscript Jasmin Beanshell using the link below: Download: JAVA PROGRAMMING LANGUAGE FAMILY GODIVA SCALA PROCESSING ASPECTJ GROOVY JAVAFX SCRIPT EINSTEIN J SHARP JUDOSCRIPT JASMIN BEANSHELL PDF The writers of Java Programming Language Family Godiva Scala Processing Aspectj Groovy Javafx Script Einstein J Sharp Judoscript Jasmin Beanshell have made all reasonable attempts to offer latest and precise information and facts for the readers of this publication. The creators will not be held accountable for any unintentional flaws or omissions that may be found. -

Hg Mercurial Cheat Sheet Serge Y

Hg Mercurial Cheat Sheet Serge Y. Stroobandt Copyright 2013–2020, licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA #This page is work in progress! Much of the explanatory text still needs to be written. Nonetheless, the basic outline of this page may already be useful and this is why I am sharing it. In the mean time, please, bare with me and check back for updates. Distributed revision control Why I went with Mercurial • Python, Mozilla, Java, Vim • Mercurial has been better supported under Windows. • Mercurial also offers named branches Emil Sit: • August 2008: Mercurial offers a comfortable command-line experience, learning Git can be a bit daunting • December 2011: Git has three “philosophical” distinctions in its favour, as well as more attention to detail Lowest common denominator It is more important that people start using dis- tributed revision control instead of nothing at all. The Pro Git book is available online. Collaboration styles • Mercurial working practices • Collaborating with other people Use SSH shorthand 1 Installation $ sudo apt-get update $ sudo apt-get install mercurial mercurial-git meld Configuration Local system-wide configuration $ nano .bashrc export NAME="John Doe" export EMAIL="[email protected]" $ source .bashrc ~/.hgrc on a client user@client $ nano ~/.hgrc [ui] username = user@client editor = nano merge = meld ssh = ssh -C [extensions] convert = graphlog = mq = progress = strip = 2 ~/.hgrc on the server user@server $ nano ~/.hgrc [ui] username = user@server editor = nano merge = meld ssh = ssh -C [extensions] convert = graphlog = mq = progress = strip = [hooks] changegroup = hg update >&2 Initiating One starts with initiate a new repository. -

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

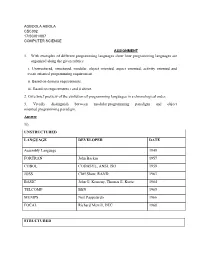

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

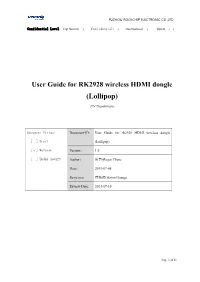

User Guide for RK2928 Wireless HDMI Dongle (Lollipop)

FUZHOU ROCKCHIP ELECTRONIC CO.,LTD Confidential Level:Top Secret( ) Confidential( ) Internal use( ) Open( √ ) User Guide for RK2928 wireless HDMI dongle (Lollipop) (TV Department) Document Status: Document ID: User Guide for rk2928 HDMI wireless dongle [ ] Draft (Lollipop) [√] Release Version: 1.0 [ ] Under modify Author: 陈智(Roger Chen) Date: 2013-07-08 Reviewer: 黄激流(Aaron Huang) Review Date: 2013-07-10 Page 1 of 41 FUZHOU ROCKCHIP ELECTRONIC CO.,LTD History Version Author Date Description V0.1 陈智(Roger Chen) 2013/6/5 Created V0.2 周小丽(Lily zhou) 2013/7/4 Add Chapter 3 V0.3 陈智(Roger Chen) 2013/7/5 Modify Chapter 3 V0.4 陈智(Roger Chen) 2013/7/9 Modify 2.2 (2), 2.2(3), 2.4 V1.0 陈智(Roger Chen) 2013/7/10 Release Page 2 of 41 FUZHOU ROCKCHIP ELECTRONIC CO.,LTD Content 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2 HOW TO USE DONGLE ............................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 MIRACAST(WFD) ....................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 DLNA ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 1) CONNECT TO DONGLE ................................................................................................................................... 6 2) CONNECT