The Hegemony of Heritage: Ritual and the Record in Stone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application No First Name Last Name Dob Domicile

ONLINE DOMICILE_ HSE_PE ONLINE HSE_50 GEND _ASS_5 MERIT_ APPLICATION_NO FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME DOB DISTRICT_ CASTE RCENTA _ASS_S _WEIGH ER 0_WEIG MARKS NAME GE CORE TAGE HTAGE 030412054771 AMIT TRIPATHI 31/07/1979 Jabalpur UR M 78.22 83 39.11 41.5 80.61 030412090866 NEERAJ KURARIYA 10/11/1988 Jabalpur UR M 84.22 76 42.11 38 80.11 030412050851 AMIT KURARIA 18/07/1979 Jabalpur UR M 73.78 85 36.89 42.5 79.39 030412033902 NITESH YADAV 20/04/1990 Jabalpur OBC M 75.78 79 37.89 39.5 77.39 030412003591 PIYUSH KANT VISHWAKARMA 17/06/1987 Jabalpur OBC M 85.11 67 42.56 33.5 76.06 030412017892 SHALINI SONI 21/07/1989 Jabalpur OBC F 79.78 72 39.89 36 75.89 030412067488 RUCHI KOSHTA 25/05/1988 Jabalpur OBC F 87.78 62 43.89 31 74.89 030412004013 PRABHAT PAROHA 01/08/1987 Jabalpur UR M 83.33 66 41.67 33 74.67 030412042225 SUDHANSU KUMAR 17/06/1989 Jabalpur UR M 77.11 72 38.56 36 74.56 030412077856 AARTI AGRAWAL 21/10/1989 Jabalpur UR F 90.67 58 45.34 29 74.34 030412074769 AJEET SINGH RAGHUWANSHI 01/07/1989 Jabalpur UR M 82.67 65 41.34 32.5 73.84 030412104573 POOJA AHUJA 09/05/1988 Jabalpur UR F 80.67 66 40.34 33 73.34 030412060585 UPENDRA MISHRA 10/03/1987 Jabalpur UR M 78.44 68 39.22 34 73.22 030412073393 ASHUTOSH MOGHE 28/10/1979 Jabalpur UR M 78.22 68 39.11 34 73.11 030412060496 SWATI AGRAHARI 06/08/1989 Jabalpur UR F 86 60 43 30 73 030412064398 MANISH KUMAR RAI 20/10/1986 Jabalpur OBC M 78.89 67 39.45 33.5 72.95 030412082906 ASHISH KUMAR JAIN 12/03/1986 Jabalpur UR M 86.67 59 43.34 29.5 72.84 030412084151 RATAN CHAKRAWARTI 28/04/1988 Jabalpur OBC M -

Not Eligible) - General

LIST OF STUDENTS UNDER SPECIAL SCHOLARSHIP SCHEME FOR J&K 2013-14 (NOT ELIGIBLE) - GENERAL DATE S.N CA FIRST MIDDLE LAST CATEG COLLEGE FATHER’S OF COURSE NAME REASON O. NID NAME NAME NAME NAME ORY NAME BIRTH ABHILASHI SHAKEEL 13-11- ORIGINAL DOMICILE, INCOME CERTIFICATE 1 SHADAB AHMAD MANHAS SEBC GROUP OF B PHARMA MANHAS 1996 NOT PRODUCED INSTITUTE ABHILASHI GH MOHD. 01/01/19 ORIGINAL INCOME CERTIFICATE NOT 2 ABID HUSSAIN RATHER OPEN GROUP OF B.PHARMA RATHER 95 PRODUCED INSTITUTE ADESH 455 SH. CHUNI 7-FEB- B.SC MRI CT 3 VISHALI . SHARMA OPEN UNIVERSITY,B INCOME CERTIFICATE NOT PRODUCED 58 LAL 1995 TECHNOLOGY ATHINDA MANZOOR ADESH 459 MEHWIS MANZOO 31-MAR- BACHELOR 4 KHAN AHMAD OPEN UNIVERSITY,B INCOME CERTIFICATE NOT PRODUCED 15 H R 1993 PHYSIOTHERAPY(BPT) KHAN ATHINDA ADHUNIK MOHD INSTITUTE OF 385 8-MAR- 5 AZAD ASHRAF KAWA ASHRAF OPEN EDUCATION & BCA DOMICILE CERTIFICATE NOT PRODUCED 41 1994 KAWA RESEARCH, GHAZIABAD SH. ALWAR 405 BURHA IRSHAD 6-AUG- 6 IRSHAD DEV OPEN PHARMACY B.PHARMACY MANAGEMENT QUOTA 82 N AHMAD 1994 COLLEGE DEV ALWAR 405 MUZAMI SH. MOHD 28-SEP- 7 AYOOB AYOOB SEBC PHARMACY B.PHARMACY MANAGEMENT QUOTA 97 L AYOOB 1996 COLLEGE MUNEER AMAR JYOTI 399 MEHREE 1-JUL- BACHLOR IN 8 SYED MUNEER AHMAD OPEN CHARITABLE PROOF OF ADMISSION IS NOT SUBMITTED 84 N 1991 PHYSIOTHERAPY NAQASH TRUST AMITY LAW 474 MOHAN 18-JUL- 9 TARUN MOHAN SHARMA OPEN SCHOOL BA LLB 12TH FROM OUTSIDE J&K 34 LAL 1994 NOIDA AMRITSAR COLLEGE OF AB 427 16-FEB- HOTEL 10 AABID QAYOOM QAYOOM OPEN B.SC INCOME CERTIFICATE NOT PRODUCED 53 1995 MANAGEMENT WANI AND -

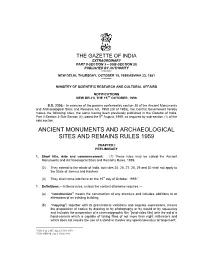

The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Rules, 1959

THE GAZETTE OF INDIA EXTRAORDINARY PART II-SECTION 3 – SUB-SECTION (ii) PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ******** NEW DELHI, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 15, 1959/ASVINA 23, 1881 ******** MINISTRY OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS NOTIFICATIONS NEW DELHI, THE 15TH OCTOBER, 1959 S.O. 2306.- In exercise of the powers conferred by section 38 of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sires and Remains Act, 1958 (24 of 1958), the Central Government hereby makes the following rules, the same having been previously published in the Gazette of India, Part II-Section 3-Sub-Section (ii), dated the 8th August, 1959, as required by sub-section (1) of the said section. ANCIENT MONUMENTS AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES AND REMAINS RULES 1959 CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY 1. Short title, date and commencement: (1) These rules may be called the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Rules, 1959. (2) They extend to the whole of India, but rules 24, 25, 27, 28, 29 and 30 shall not apply to the State of Jammu and Kashmir. (3) They shall come into force on the 15th day of October, 1959.1 1. Definitions.—In these rules, unless the context otherwise requires.— (a) “construction” means the construction of any structure and includes additions to or alterations of an existing building; (b) “copying”, together with its grammatical variations and cognate expressions, means the preparation of copies by drawing or by photography or by mould or by squeezing and includes the preparation of a cinematographic film 2[and video film] with the aid of a hand-camera which is capable of taking films of not more than eight millimeters and which does not require the use of a stand or involve any special previous arrangement; 1 Vide S.O. -

Rajasthan List.Pdf

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Rajasthan Date Of Area Of S.No Name Category Father's Name Address Enrol. No. & Date App'n Practice Village Lodipura Post Kamal Kumar Sawai Madho Lal R/2917/2003 1 Obc 01.05.18 Khatupura ,Sawai Gurjar Madhopur Gurjar Dt.28.12.03 Madhopur,Rajasthan Village Sukhwas Post Allapur Chhotu Lal Sawai Laddu Lal R/1600/2004 2 Obc 01.05.18 Tehsil Khandar,Sawai Gurjar Madhopur Gurjar Dt.02.10.04 Madhopur,Rajasthan Sindhu Farm Villahe Bilwadi Ram Karan R/910/2007 3 Obc 01.05.18 Shahpura Suraj Mal Tehsil Sindhu Dt.22.04.07 Viratnagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Opposite 5-Kha H.B.C. Sanjay Nagar Bhatta Basti R/1404/2004 4 Abdul Kayam Gen 02.05.18 Jaipur Bafati Khan Shastri Dt.02.10.04 Nagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Jajoria Bhawan Village- Parveen Kumar Ram Gopal Keshopura Post- Vaishali R/857/2008 5 Sc 04.05.18 Jaipur Jajoria Jajoria Nagar Ajmer Dt.28.06.08 Road,Jaipur,Rajasthan Kailash Vakil Colony Court Road Devendra R/3850/2007 6 Obc 08.05.18 Mandalgarh Chandra Mandalgarh,Bhilwara,Rajast Kumar Tamboli Dt.16.12.07 Tamboli han Bhagwan Sahya Ward No 17 Viratnagar R/153/1996 7 Mamraj Saini Obc 03.05.18 Viratnagar Saini ,Jaipur,Rajasthan Dt.09.03.96 156 Luharo Ka Mohalla R/100/1997 8 Anwar Ahmed Gen 04.05.18 Jaipur Bashir Ahmed Sambhar Dt.31.01.97 Lake,Jaipur,Rajasthan B-1048-49 Sanjay Nagar Mohammad Near 17 No Bus Stand Bhatta R/1812/2005 9 Obc 04.05.18 Jaipur Abrar Hussain Salim Basti Shastri Dt.01.10.05 Nagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Vill Bislan Post Suratpura R/651/2008 10 Vijay Singh Obc 04.05.18 Rajgarh Dayanand Teh Dt.05.04.08 Rajgarh,Churu,Rajasthan Late Devki Plot No-411 Tara Nagar-A R/41/2002 11 Rajesh Sharma Gen 05.05.18 Jaipur Nandan Jhotwara,Jaipur,Rajasthan Dt.12.01.02 Sharma Opp Bus Stand Near Hanuman Ji Temple Ramanand Hanumangar Rameshwar Lal R/29/2002 12 Gen 05.05.18 Hanumangarh Sharma h Sharma Dt.17.01.02 Town,Hanumangarh,Rajasth an Ward No 23 New Abadi Street No 17 Fatehgarh Hanumangar Gangabishan R/3511/2010 13 Om Prakash Obc 07.05.18 Moad Hanumangarh h Bishnoi Dt.14.08.10 Town,Hanumangarh,Rajasth an P.No. -

LIST of INDIAN CITIES on RIVERS (India)

List of important cities on river (India) The following is a list of the cities in India through which major rivers flow. S.No. City River State 1 Gangakhed Godavari Maharashtra 2 Agra Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 3 Ahmedabad Sabarmati Gujarat 4 At the confluence of Ganga, Yamuna and Allahabad Uttar Pradesh Saraswati 5 Ayodhya Sarayu Uttar Pradesh 6 Badrinath Alaknanda Uttarakhand 7 Banki Mahanadi Odisha 8 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 9 Baranagar Ganges West Bengal 10 Brahmapur Rushikulya Odisha 11 Chhatrapur Rushikulya Odisha 12 Bhagalpur Ganges Bihar 13 Kolkata Hooghly West Bengal 14 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 15 New Delhi Yamuna Delhi 16 Dibrugarh Brahmaputra Assam 17 Deesa Banas Gujarat 18 Ferozpur Sutlej Punjab 19 Guwahati Brahmaputra Assam 20 Haridwar Ganges Uttarakhand 21 Hyderabad Musi Telangana 22 Jabalpur Narmada Madhya Pradesh 23 Kanpur Ganges Uttar Pradesh 24 Kota Chambal Rajasthan 25 Jammu Tawi Jammu & Kashmir 26 Jaunpur Gomti Uttar Pradesh 27 Patna Ganges Bihar 28 Rajahmundry Godavari Andhra Pradesh 29 Srinagar Jhelum Jammu & Kashmir 30 Surat Tapi Gujarat 31 Varanasi Ganges Uttar Pradesh 32 Vijayawada Krishna Andhra Pradesh 33 Vadodara Vishwamitri Gujarat 1 Source – Wikipedia S.No. City River State 34 Mathura Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 35 Modasa Mazum Gujarat 36 Mirzapur Ganga Uttar Pradesh 37 Morbi Machchu Gujarat 38 Auraiya Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 39 Etawah Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 40 Bangalore Vrishabhavathi Karnataka 41 Farrukhabad Ganges Uttar Pradesh 42 Rangpo Teesta Sikkim 43 Rajkot Aji Gujarat 44 Gaya Falgu (Neeranjana) Bihar 45 Fatehgarh Ganges -

Sati – Suicide by Widows Sanctioned by Hindu Scriptures and Society? by Latha Nrugham

SUICIDOLOGI 2013, ÅRG. 18, NR. 1 Sati – suicide by widows sanctioned by Hindu scriptures and society? By Latha Nrugham Introduction It is not a contract between two indivi- such as distress about and fear of damage duals but is the union of two individuals to body issue and death itself, in addition In India, sati is the term usually applied to a Hindu widow dressed as a bride coming together in all ways to support to being endowed with the ability to ceremoniously ascending alive the funeral each other for the goals of life laid down endure fire in silence. A wife, who was pyre of her dead husband and being burnt in the Vedic scriptures. also a mother or pregnant, could not to ashes on that pyre. Such a person is I refer to the Vedic scriptures because consider sati, as that would make the said to have become a sati by this deed, they are several texts, not one book. These child an orphan. texts can be grouped into two: Shruti one who did not become a widow, but Sati in the Vedic scriptures remained a wife until her last breath. (heard) and Smriti (remembered). Shruti Outside India, the word sati is commonly has verses that are composed as a result Vedic scriptures do not have a central understood as suicide sanctioned by Hindu of stable consciousness states of insight authority like the Pope for Christians or scriptures and widely practiced in India resulting from deep meditation for several even organised dissemination of its con- today. In order to comment on this under- years and has three divisions: the four tents like Islamic madrassas (schools of standing, I will first describe sati in the Vedas, the main Upanishads and the Quran) or the Sunday schools of Christi- Hindu scriptures and then present sati in Brahmasutras. -

BHIC-105 English.Pmd

BHIC-105 HISTORY OF INDIA-III (750 - 1206 CE) School of Social Sciences Indira Gandhi National Open University EXPERT COMMITTEE Prof. Kapil Kumar (Convenor) Prof. Makhan Lal Chairperson Director Faculty of History Delhi Institute of Heritage, School of Social Sciences Research and Management IGNOU, New Delhi New Delhi Prof. P. K. Basant Dr. Sangeeta Pandey Faculty of Humanities and Languages Faculty of History Jamia Milia Islamia School of Social Sciences New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi Prof. D. Gopal Director, SOSS, IGNOU, New Delhi Course Coordinator : Prof. Nandini Sinha Kapur COURSE TEAM Prof. Nandini Sinha Kapur Dr. Suchi Dayal Dr. Abhishek Anand COURSE PREPARATION TEAM Unit no. Course Writer Dr. Khushboo Kumari Academic Counsellor Dr. Suchi Dayal 1 Non Collegiate Women’s Education Board Academic Consultant, Faculty of History School (Bharati College), University of Delhi of Social Sciences, IGNOU, New Delhi Dr. Avantika Sharma Dr. Ashok Shettar 8 2* Department of History, I.P. College for Karnataka University, Dharwad Women, Delhi University, Delhi Dr. Pintu Kumar 3** Dr. Richa Singh Assistant Professor 9 Ph.D from Centre for Historical Studies Motilal Nehru College (Evening) Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Delhi University Professor Champaklakshmi Dr. Naina Dasgupta 10****** Retired from Center for Historical Studies National Open School, Kailash Colony Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi New Delhi and Dr. Sangeeta Pandey Dr. V. K. Jain Faculty of History Department of History School of Social Sciences IGNOU, New Delhi University of Delhi, Delhi 4*** Prof. Y. Subbarayalu, Head Prof. Harbans Mukhia Indology Department, Retired from Centre for Historical Studies French Institute of Pondicherry, Puducherry Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Dr. -

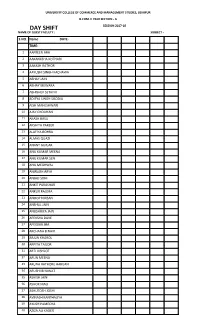

Day Shift Session 2017-18 Name of Guest Faculty : Subject - S.No

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. II YEAR SECTION - A DAY SHIFT SESSION 2017-18 NAME OF GUEST FACULTY : SUBJECT - S.NO. Name DATE- TIME- 1 AAFREEN ARA 2 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI 3 AAKASH RATHOR 4 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA 5 ABHAY JAIN 6 ABHAY MEWARA 7 ABHISHEK SETHIYA 8 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA 9 AISH MAHESHWARI 10 AJAY CHOUHAN 11 AKASH BASU 12 AKSHITA PAREEK 13 ALAFIYA BOHRA 14 ALMAS QUAZI 15 ANANT GURJAR 16 ANIL KUMAR MEENA 17 ANIL KUMAR SEN 18 ANIL MEGHWAL 19 ANIRUDH ARYA 20 ANJALI SONI 21 ANKIT PARASHAR 22 ANKUR RAJORA 23 ANOOP NIRBAN 24 ANSHUL JAIN 25 ANUSHRIYA JAIN 26 APEKSHA DAVE 27 APEKSHA JHA 28 ARCHANA B NAIR 29 ARJUN KHAROL 30 ARPITA TAILOR 31 ARTI VISHLOT 32 ARUN MEENA 33 ARUNA RATHORE HARIJAN 34 ARUSHI BIYAWAT 35 ASHISH JAIN 36 ASHOK MALI 37 ASHUTOSH JOSHI 38 AVINASH KANTHALIYA 39 AYUSH PAMECHA 40 AZIZA ALI KADER 41 BATUL 42 BHARAT LOHAR 43 BHARAT MEENA 44 BHARAT PURI GOSWAMI 45 BHAVIN JAIN 46 BHAWANA SOLANKI 47 BHUMIKA JAIN 48 BHUMIKA PALIYA 49 BHUMIT SEVAK 50 BHUPENDRA JAIN 51 BINISH KHAN 52 BURHANUDDIN MOOMIN 53 CHANCHAL SOLANKI 54 CHETAN KOTIA 55 DAKSH VYAS 56 DANISH KHAN 57 DARSHIT DOSHI 58 DEEPAK NAGDA 59 DEEPAK SHRIMALI 60 DEEPIKA SAHU 61 DEEPIKA SINGH KHARWAR 62 DEEPIKA YADAV 63 DEEPTI KUMAWAT 64 DHRUVIT KUMAWAT 65 DIKSHANT VAIRAGI 66 DINESH KUMAR MEENA 67 DINESH NAGDA 68 DINESH RAJPUROHIT 69 DIPESH JAIN 70 DIVYA GUPTA 71 DIVYA JAIN 72 DIVYA MALI 73 DIVYA NAKWAL 74 DIVYA SONI 75 DURGA BHATT 76 DURGA SHANKAR MALI 77 FATEMA BOHRA 78 FIRDOSH MANSURI 79 GAJENDRA MENARIA 80 GAJENDRA PUSHKARNA Signature of Guest Faculty DEAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. -

Gadre 1943.Pdf

- Sri Pratapasimha Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantha-maia MEMOIR No. II. IMPORTANT INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE BARODA STATE. * Vol. I. Price Rs. 5-7-0 A. S. GADRE INTRODUCTION I have ranch pleasure in writing a short introduction to Memoir No, II in 'Sri Pratapsinh Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantharnala Series', Mr, Gadre has edited 12 of the most important epigraphs relating to this part of India some of which are now placed before the public for the first time. of its These throw much light on the history Western India and social and economic institutions, It is hoped that a volume containing the Persian inscriptions will be published shortly. ' ' Dilaram V. T, KRISHNAMACHARI, | Baroda, 5th July 1943. j Dewan. ii FOREWORD The importance of the parts of Gujarat and Kathiawad under the rule of His Highness the Gaekwad of Baroda has been recognised by antiquarians for a the of long time past. The antiquities of Dabhoi and architecture Northern the Archaeo- Gujarat have formed subjects of special monographs published by of India. The Government of Baroda did not however realise the logical Survey of until a necessity of establishing an Archaeological Department the State nearly decade ago. It is hoped that this Department, which has been conducting very useful work in all branches of archaeology, will continue to flourish under the the of enlightened rule of His Highness Maharaja Gaekwad Baroda. , There is limitless scope for the activities of the Archaeological Department in Baroda. The work of the first Gujarat Prehistoric Research Expedition in of the cold weather of 1941-42 has brought to light numerous remains stone age and man in the Vijapuf and Karhi tracts in the North and in Sankheda basin. -

Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªrobes of Honourº in India

Folklore 112 (2001):23± 45 RESEARCH ARTICLE Killer Khilats, Part 1: Legends of Poisoned ªRobes of Honourº in India Michelle Maskiell and Adrienne Mayor Abstract This article presents seven historical legends of death by Poison Dress that arose in early modern India. The tales revolve around fears of symbolic harm and real contamination aroused by the ancient Iranian-in¯ uenced customs of presenting robes of honour (khilats) to friends and enemies. From 1600 to the early twentieth century, Rajputs, Mughals, British, and other groups in India participated in the development of tales of deadly clothing. Many of the motifs and themes are analogous to Poison Dress legends found in the Bible, Greek myth and Arthurian legend, and to modern versions, but all seven tales display distinc- tively Indian characteristics. The historical settings reveal the cultural assump- tions of the various groups who performed poison khilat legends in India and display the ambiguities embedded in the khilat system for all who performed these tales. Introduction We have gathered seven ª Poison Dressº legends set in early modern India, which feature a poison khilat (Arabic, ª robe of honourº ). These ª Killer Khilatº tales share plots, themes and motifs with the ª Poison Dressº family of folklore, in which victims are killed by contaminated clothing. Because historical legends often crystallise around actual people and events, and re¯ ect contemporary anxieties and the moral dilemmas of the tellers and their audiences, these stories have much to tell historians as well as folklorists. The poison khilat tales are intriguing examples of how recurrent narrative patterns emerge under cultural pressure to reveal fault lines within a given society’s accepted values and social practices. -

The Historical Thar Desert of India

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 12 No 4 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) www.richtmann.org July 2021 . Research Article © 2021 Manisha Choudhary. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Received: 14 May 2021 / Accepted: 28 June 2021 / Published: 8 July 2021 The Historical Thar Desert of India Manisha Choudhary Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Delhi, India DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/mjss-2021-0029 Abstract Desert was a ‘no-go area’ and the interactions with it were only to curb and contain the rebelling forces. This article is an attempt to understand the contours and history of Thar Desert of Rajasthan and to explore the features that have kept the various desert states (Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Barmer, Bikaner etc.) and their populace sustaining in this region throughout the ages, even when this region had scarce water resources and intense desert with huge and extensive dunes. Through political control the dynasts kept the social organisation intact which ensured regular incomes for their respective dynasties. Through the participation of various social actors this dry and hot desert evolved as a massive trade emporium. The intense trade activities of Thar Desert kept the imperial centres intact in this agriculturally devoid zone. In the harsh environmental conditions, limited means, resources and the objects, the settlers of this desert were able to create a huge economy that sustained effectively. The economy build by them not only allowed the foundation and formation of the states, it also ensured their continuation and expansion over the centuries. -

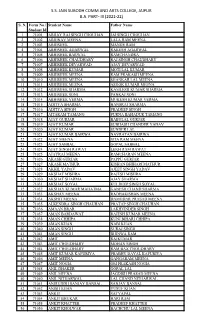

Ss Jain Subodh Comm and Arts College, Jaipur Ba Part

S.S. JAIN SUBODH COMM AND ARTS COLLEGE, JAIPUR B.A. PART- III (2021-22) S. N. Form No./ Student Name Father Name Student Id 1 71001 ABHAY RAJ SINGH CHOUHAN JAI SINGH CHOUHAN 2 71002 ABHINAV MEENA LALA RAM MEENA 3 71003 ABHISHEK MANGE RAM 4 71004 ABHISHEK AGARWAL RAKESH AGARWAL 5 71005 ABHISHEK BARWAL RAMCHANDRA 6 71006 ABHISHEK CHAUDHARY RAJ SINGH CHAUDHARY 7 71007 ABHISHEK DEVARWAD AJAY DEVARWAD 8 71008 ABHISHEK KUMAR MOTI LAL KUMAR 9 71009 ABHISHEK MEENA RAM PRAKASH MEENA 10 71010 ABHISHEK MEENA SHANKAR LAL MEENA 11 71011 ABHISHEK MEENA ASHOK KUMAR MEENA 12 71012 ABHISHEK SHARMA KAMLESH KUMAR SHARMA 13 71013 ABHISHEK SONI PANKAJ SONI 14 71014 ABHISHEK VERMA MUKESH KUMAR VERMA 15 71015 ADITYA SHARMA HANSRAJ SHARMA 16 71016 ADITYA SINGH PRADEEP SINGH 17 71017 AITARAM TAMANG PURNA BAHADUR TAMANG 18 71018 AJAY GURJAR BABULAL GURJAR 19 71019 AJAY KUMAR SUBHASH CHANDER YADAV 20 71020 AJAY KUMAR SUNDER LAL 21 71021 AJAY KUMAR BAIRWA NAVRATAN BAIRWA 22 71022 AJAY MEENA SITA RAM MEENA 23 71023 AJAY SABBAL GOPAL SABBAL 24 71024 AJAY SINGH RAWAT LEKH RAM RAWAT 25 71025 AJAYRAJ MEENA RAMCHARAN MEENA 26 71026 AKASH GURJAR PAPPU GURJAR 27 71027 AKASH MATHUR KISHAN BHIHARI MATHUR 28 71028 AKHIL YADAV AJEET SINGH YADAV 29 71029 AKSHAT MISHRA RAJESH MISHRA 30 71030 AKSHAT SHARMA AJAY SHARMA 31 71031 AKSHAT SOYAL KULDEEP SINGH SOYAL 32 71032 AKSHAY KUMAR MAHATMA GANESH CHAND SHARMA 33 71033 AKSHAY MEENA RADHAKISHAN MEENA 34 71034 AKSHIT MEENA DAMODAR PRASAD MEENA 35 71035 ALKENDRA SINGH CHAUHAN PRATAP SINGH CHAUHAN 36 71036 AMAAN BRAR LAKHVINDER SINGH